39 What is Consciousness?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand what is meant by consciousness and attention

- Explain how circadian rhythms are involved in regulating the sleep-wake cycle, and how circadian cycles can be disrupted

- Discuss the concept of sleep debt

Consciousness describes our awareness of internal and external stimuli. Awareness of internal stimuli includes feeling pain, hunger, thirst, sleepiness, and being aware of our thoughts and emotions. Awareness of external stimuli includes experiences such as seeing the light from the sun, feeling the warmth of a room, and hearing the voice of a friend.

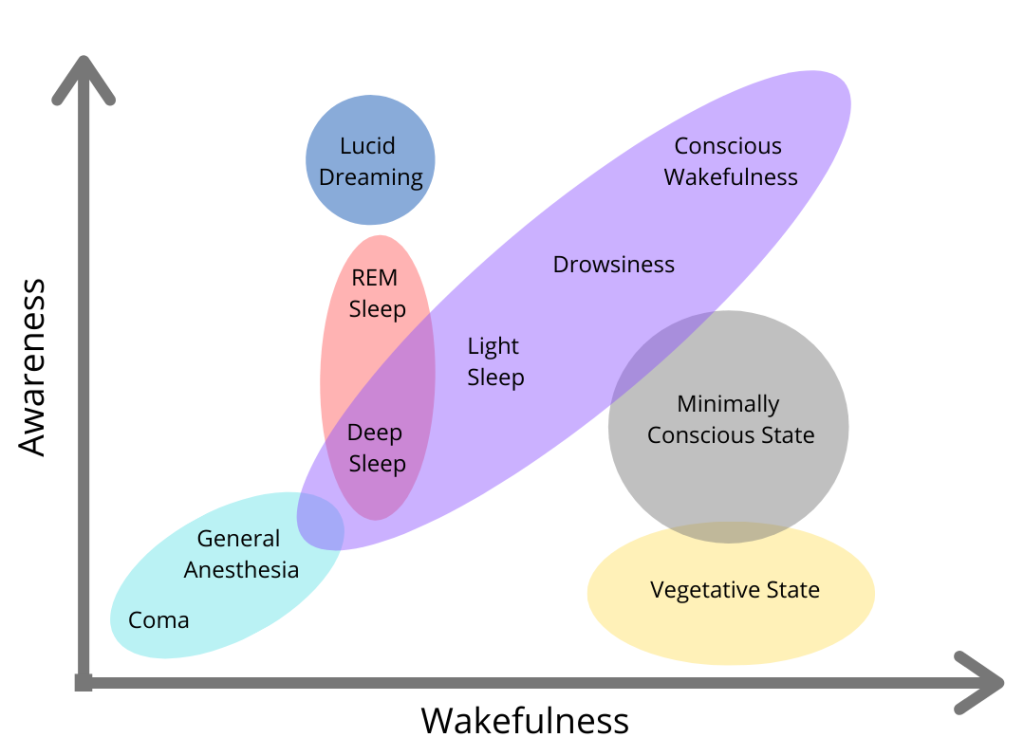

We experience different states of consciousness and different levels of awareness on a regular basis. We might even describe consciousness as a continuum that ranges from full awareness to a deep sleep. Sleep is a state marked by relatively low levels of physical activity and reduced sensory awareness that is distinct from periods of rest that occur during wakefulness. Wakefulness is characterized by high levels of sensory awareness, thought, and behaviour. Beyond being awake or asleep, there are many other states of consciousness people experience. These include daydreaming, intoxication, and unconsciousness due to anesthesia. We might also experience unconscious states of being via drug-induced anesthesia for medical purposes. Often, we are not completely aware of our surroundings, even when we are fully awake. For instance, have you ever daydreamed while driving home from work or school without really thinking about the drive itself? You were capable of engaging in the all of the complex tasks involved with operating a motor vehicle even though you were not aware of doing so. Many of these processes, like much of psychological behaviour, are rooted in our biology. More information on the dimensions of consciousness is available in the video below, and in Figure SC.2.

TRICKY TOPIC: MEASURING CONSCIOUSNESS

For a full transcript of this video, click here

Attention

William James wrote extensively about attention in the late 1800s. An often quoted passage (James, 1890-1983) beautifully captures how intuitively obvious the concept of attention is, while it remains very difficult to define in measurable, concrete terms: Everyone knows what attention is. It is the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration of consciousness are of its essence. It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others.

Notice that this description touches on the conscious nature of attention, as well as the notion that what is in consciousness is often controlled voluntarily but can also be determined by events that capture our attention. Implied in this description is the idea that we seem to have a limited capacity for information processing, and that we can only attend to or be consciously aware of a small amount of information at any given time.

Many aspects of attention have been studied in the field of psychology. In some respects, we define different types of attention by the nature of the task used to study it. For example, a crucial issue in World War II was how long an individual could remain highly alert and accurate while watching a radar screen for enemy planes, and this problem led psychologists to study how attention works under such conditions. When watching for a rare event, it is easy to allow concentration to lag. (This a continues to be a challenge today for TSA agents, charged with looking at images of the contents of your carry-on items in search of knives, guns, or shampoo bottles larger than 3 oz.) Attention in the context of this type of search task refers to the level of sustained attention or vigilance one can maintain. In contrast, divided attention tasks allow us to determine how well individuals can attend to many sources of information at once. Spatial attention refers specifically to how we focus on one part of our environment and how we move attention to other locations in the environment. These are all examples of different aspects of attention, but an implied element of most of these ideas is the concept of selective attention; some information is attended to while other information is intentionally blocked out.

Selective attention is the ability to select certain stimuli in the environment to process, while ignoring distracting information. One way to get an intuitive sense of how attention works is to consider situations in which attention is used. A party provides an excellent example for our purposes. Many people may be milling around, there is a dazzling variety of colours and sounds and smells, the buzz of many conversations is striking. There are so many conversations going on; how is it possible to select just one and follow it? You don’t have to be looking at the person talking; you may be listening with great interest to some gossip while pretending not to hear. However, once you are engaged in conversation with someone, you quickly become aware that you cannot also listen to other conversations at the same time. You also are probably not aware of how tight your shoes feel or of the smell of a nearby flower arrangement. On the other hand, if someone behind you mentions your name, you typically notice it immediately and may start attending to that (much more interesting) conversation. This situation highlights an interesting set of observations. We have an amazing ability to select and track one voice, visual object, etc., even when a million things are competing for our attention, but at the same time, we seem to be limited in how much we can attend to at one time, which in turn suggests that attention is crucial in selecting what is important.

This cocktail party scenario is the quintessential example of selective attention, and it is essentially what some early researchers tried to replicate under controlled laboratory conditions as a starting point for understanding the role of attention in perception (e.g., Cherry, 1953; Moray, 1959). In particular, they used dichotic listening and shadowing tasks to evaluate the selection process. Dichotic listening simply refers to the situation when two messages are presented simultaneously to an individual, with one message in each ear. In order to control which message the person attends to, the individual is asked to repeat back or “shadow” one of the messages as they hear it. For example, let’s say that a story about a camping trip is presented to Finch’s left ear, and a story about Wayne Gretzky is presented to their right ear. The typical dichotic listening task would have Finch repeat the story presented to one ear as they hear it. Can Finch do that without being distracted by the information in the other ear?

People can become pretty good at the shadowing task, and they can easily report the content of the message that they attend to. But what happens to the ignored message? Typically, people can tell you if the ignored message was a man’s or a woman’s voice, or other physical characteristics of the speech, but they cannot tell you what the message was about. In fact, many studies have shown that people in a shadowing task were not aware of a change in the language of the message (e.g., from English to German; Cherry, 1953), and they didn’t even notice when the same word was repeated in the unattended ear more than 35 times (Moray, 1959)! Only the basic physical characteristics, such as the pitch of the unattended message, could be reported.

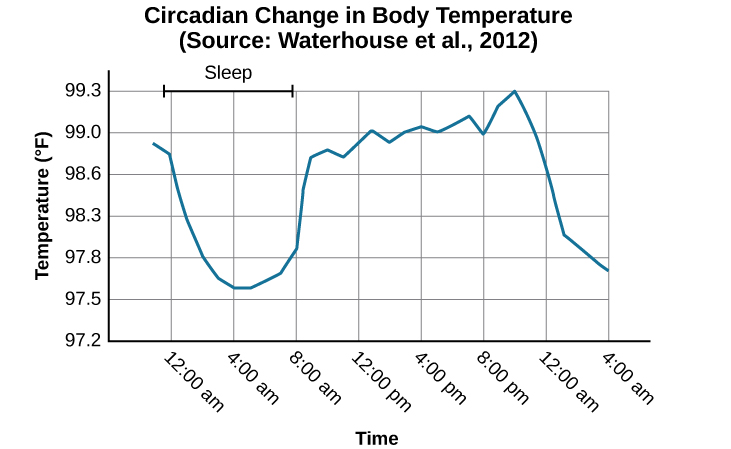

Biological Rhythms

Biological rhythms are internal rhythms of biological activity. The menstrual cycle is an example of a biological rhythm—a recurring, cyclical pattern of bodily changes. One complete menstrual cycle takes about 28 days—a lunar month—but many biological cycles are much shorter. For example, body temperature fluctuates cyclically over a 24-hour period (Figure SC.3). Alertness is associated with higher body temperatures, and sleepiness with lower body temperatures.

Problems With Circadian Rhythms

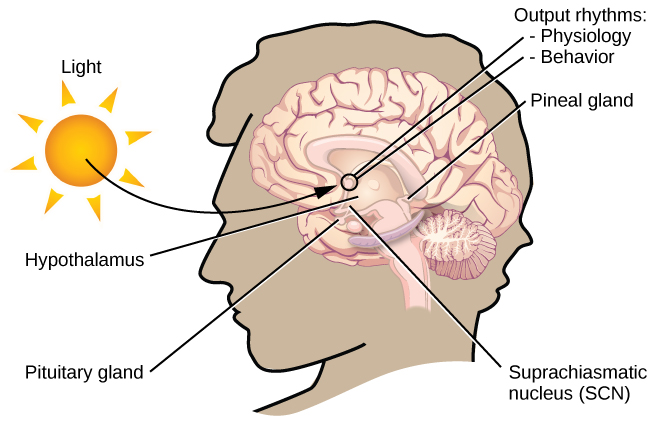

Generally, and for most people, our circadian cycles are aligned with the outside world. For example, most people sleep during the night and are awake during the day. One important regulator of sleep-wake cycles is the hormone melatonin. The pineal gland, an endocrine structure located inside the brain that releases melatonin, is thought to be involved in the regulation of various biological rhythms and of the immune system during sleep (Hardeland, Pandi-Perumal, & Cardinali, 2006). Melatonin release is stimulated by darkness and inhibited by light.

There are individual differences in regard to our sleep-wake cycle. For instance, some people would say they are morning people, while others would consider themselves to be night owls. These individual differences in circadian patterns of activity are known as a person’s chronotype, and research demonstrates that morning larks and night owls differ with regard to sleep regulation (Taillard, Philip, Coste, Sagaspe, & Bioulac, 2003). Sleep regulation refers to the brain’s control of switching between sleep and wakefulness as well as coordinating this cycle with the outside world.

Link to Learning

Watch this brief video about circadian rhythms and how they affect sleep to learn more.

Disruptions of Normal Sleep

Whether lark, owl, or somewhere in between, there are situations in which a person’s circadian clock gets out of synchrony with the external environment. One way that this happens involves traveling across multiple time zones. When we do this, we often experience jet lag. Jet lag is a collection of symptoms that results from the mismatch between our internal circadian cycles and our environment. These symptoms include fatigue, sluggishness, irritability, and insomnia (i.e., a consistent difficulty in falling or staying asleep for at least three nights a week over a month’s time) (Roth, 2007).

Individuals who do rotating shift work are also likely to experience disruptions in circadian cycles. Rotating shift work refers to a work schedule that changes from early to late on a daily or weekly basis. For example, a person may work from 7:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. on Monday, 3:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. on Tuesday, and 11:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. on Wednesday. In such instances, the individual’s schedule changes so frequently that it becomes difficult for a normal circadian rhythm to be maintained. This often results in sleeping problems, and it can lead to signs of depression and anxiety. These kinds of schedules are common for individuals working in health care professions and service industries, and they are associated with persistent feelings of exhaustion and agitation that can make someone more prone to making mistakes on the job (Gold et al., 1992; Presser, 1995).

Rotating shift work has pervasive effects on the lives and experiences of individuals engaged in that kind of work, which is clearly illustrated in stories reported in a qualitative study that researched the experiences of middle-aged nurses who worked rotating shifts (West, Boughton & Byrnes, 2009). Several of the nurses interviewed commented that their work schedules affected their relationships with their family. One of the nurses said,

“If you’ve had a partner who does work regular job 9 to 5 office hours . . . the ability to spend time, good time with them when you’re not feeling absolutely exhausted . . . that would be one of the problems that I’ve encountered.” (West et al., 2009, p. 114)

While disruptions in circadian rhythms can have negative consequences, there are things we can do to help us realign our biological clocks with the external environment. Some of these approaches, such as using a bright light as shown in Figure SC.5, have been shown to alleviate some of the problems experienced by individuals suffering from jet lag or from the consequences of rotating shift work. Because the biological clock is driven by light, exposure to bright light during working shifts and dark exposure when not working can help combat insomnia and symptoms of anxiety and depression (Huang, Tsai, Chen, & Hsu, 2013).

Link to Learning

Watch this video about overcoming jet lag to learn some tips.

Insufficient Sleep

When people have difficulty getting sleep due to their work or the demands of day-to-day life, they accumulate a sleep debt. A person with a sleep debt does not get sufficient sleep on a chronic basis. The consequences of sleep debt include decreased levels of alertness and mental efficiency. Interestingly, since the advent of electric light, the amount of sleep that people get has declined. While we certainly welcome the convenience of having the darkness lit up, we also suffer the consequences of reduced amounts of sleep because we are more active during the nighttime hours than our ancestors were. As a result, many of us sleep less than 7–8 hours a night and accrue a sleep debt. While there is tremendous variation in any given individual’s sleep needs, the National Sleep Foundation (n.d.) cites research to estimate that newborns require the most sleep (between 12 and 18 hours a night) and that this amount declines to just 7–9 hours by the time we are adults.

If you lie down to take a nap and fall asleep very easily, chances are you may have sleep debt. Given that college students are notorious for suffering from significant sleep debt (Hicks, Fernandez, & Pelligrini, 2001; Hicks, Johnson, & Pelligrini, 1992; Miller, Shattuck, & Matsangas, 2010), chances are you and your classmates deal with sleep debt-related issues on a regular basis. In 2015, the National Sleep Foundation updated their sleep duration hours, to better accommodate individual differences. Table SC.1 shows the new recommendations, which describe sleep durations that are “recommended”, “may be appropriate”, and “not recommended”.

| Table SC.1 Sleep Needs at Different Ages | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Recommended | May be appropriate | Not recommended |

| 0–3 months | 14–17 hours | 11–13 hours 18–19 hours |

Fewer than 11 hours More than 19 hours |

| 4–11 months | 12–15 hours | 10–11 hours 16–18 hours |

Fewer than 10 hours More than 18 hours |

| 1–2 years | 11–14 hours | 9–10 hours 15–16 hours |

Fewer than 9 hours More than 16 hours |

| 3–5 years | 10–13 hours | 8–9 hours 14 hours |

Fewer than 8 hours More than 14 hours |

| 6–13 years | 9–11 hours | 7–8 hours 12 hours |

Fewer than 7 hours More than 12 hours |

| 14–17 years | 8–10 hours | 7 hours 11 hours |

Fewer than 7 hours More than 11 hours |

| 18–25 years | 7–9 hours | 6 hours 10–11 hours |

Fewer than 6 hours More than 11 hours |

| 26–64 years | 7–9 hours | 6 hours 10 hours |

Fewer than 6 hours More than 10 hours |

| ≥65 years | 7–8 hours | 5–6 hours 9 hours |

Fewer than 5 hours More than 9 hours |

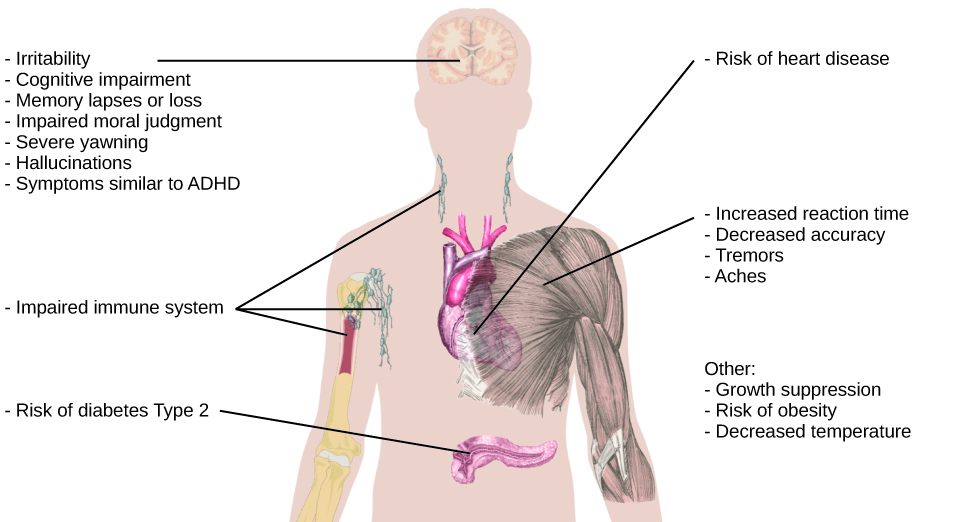

Sleep debt and sleep deprivation have significant negative psychological and physiological consequences (Figure SC.6). As mentioned earlier, lack of sleep can result in decreased mental alertness and cognitive function. In addition, sleep deprivation often results in depression-like symptoms. These effects can occur as a function of accumulated sleep debt or in response to more acute periods of sleep deprivation. It may surprise you to know that sleep deprivation is associated with obesity, increased blood pressure, increased levels of stress hormones, and reduced immune functioning (Banks & Dinges, 2007). A sleep deprived individual generally will fall asleep more quickly than if she were not sleep deprived. Some sleep-deprived individuals have difficulty staying awake when they stop moving (example sitting and watching television or driving a car). That is why individuals suffering from sleep deprivation can also put themselves and others at risk when they put themselves behind the wheel of a car or work with dangerous machinery. Some research suggests that sleep deprivation affects cognitive and motor function as much as, if not more than, alcohol intoxication (Williamson & Feyer, 2000). Research shows that the most severe effects of sleep deprivation occur when a person stays awake for more than 24 hours (Killgore & Weber, 2014; Killgore et al., 2007), or following repeated nights with fewer than four hours in bed (Wickens, Hutchins, Lauk, Seebook, 2015). For example, irritability, distractibility, and impairments in cognitive and moral judgment can occur with fewer than four hours of sleep. If someone stays awake for 48 consecutive hours, they could start to hallucinate.

Link to Learning

Check out this article designed to help you evaluate potential poor sleeping habits.

The amount of sleep we get varies across the lifespan. When we are very young, we spend up to 16 hours a day sleeping. As we grow older, we sleep less. In fact, a meta-analysis, which is a study that combines the results of many related studies, conducted within the last decade indicates that by the time we are 65 years old, we average fewer than 7 hours of sleep per day (Ohayon, Carskadon, Guilleminault, & Vitiello, 2004).