136 Mood Disorders

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish normal states of sadness and euphoria from states of depression and mania

- Describe the symptoms of major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder

- Understand the differences between major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder, and identify two subtypes of depression

- Define the criteria for a manic episode

- Understand genetic, biological, and psychological explanations of major depressive disorder

Blake cries all day and feels worthless and that life is hopeless; he cannot get out of bed. Crystal stays up all night, talks very rapidly, and went on a shopping spree in which she spent $3,000 on furniture, although she cannot afford it. Jordan recently had a baby, and feels overwhelmed, teary, anxious, and panicked practically every day since the baby was born. Jordan also believes they are a terrible parent. All these individuals demonstrate symptoms of a potential mood disorder.

Mood disorders (Figure PY.14) are characterized by severe disturbances in mood and emotions—most often depression, but also mania and elation (Rothschild, 1999). All of us experience fluctuations in our moods and emotional states, and often these fluctuations are caused by events in our lives. We become elated if our favourite team wins the World Series and dejected if a romantic relationship ends or if we lose our job. At times, we feel fantastic or miserable for no clear reason. People with mood disorders also experience mood fluctuations, but their fluctuations are extreme, distort their outlook on life, and impair their ability to function.

The DSM-5 lists two general categories of mood disorders. Depressive disorders are a group of disorders in which depression is the main feature. Depression is a vague term that, in everyday language, refers to an intense and persistent sadness. Depression is a heterogeneous mood state—it consists of a broad spectrum of symptoms that range in severity. Depressed people feel sad, discouraged, and hopeless. These individuals lose interest in activities once enjoyed, often experience a decrease in drives such as hunger and sex, and frequently doubt personal worth. Depressive disorders vary by degree, but this chapter highlights the most well-known: major depressive disorder (sometimes called unipolar depression).

Bipolar and related disorders are a group of disorders in which mania is the defining feature. Mania is a state of extreme elation and agitation. When people experience mania, they may become extremely talkative, behave recklessly, or attempt to take on many tasks simultaneously. The most recognized of these disorders is bipolar disorder.

Major Depressive Disorder

According to the DSM-5, the defining symptoms of major depressive disorder include “depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day” (feeling sad, empty, hopeless, or appearing tearful to others), and loss of interest and pleasure in usual activities (APA, 2013). In addition to feeling overwhelmingly sad most of each day, people with depression will no longer show interest or enjoyment in activities that previously were gratifying, such as hobbies, sports, sex, social events, time spent with family, and so on. Friends and family members may notice that the person has completely abandoned previously enjoyed hobbies; for example, an avid tennis player who develops major depressive disorder no longer plays tennis (Rothschild, 1999).

To receive a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, one must experience a total of five symptoms for at least a two-week period; these symptoms must cause significant distress or impair normal functioning, and they must not be caused by substances or a medical condition. At least one of the two symptoms mentioned above must be present, plus any combination of the following symptoms (APA, 2013):

- significant weight loss (when not dieting) or weight gain and/or significant decrease or increase in appetite;

- difficulty falling asleep or sleeping too much;

- psychomotor agitation (the person is noticeably fidgety and jittery, demonstrated by behaviours like the inability to sit, pacing, hand-wringing, pulling or rubbing of the skin, clothing, or other objects) or psychomotor retardation (the person talks and moves slowly, for example, talking softly, very little, or in a monotone);

- fatigue or loss of energy;

- feelings of worthlessness or guilt;

- difficulty concentrating and indecisiveness; and

- suicidal ideation: thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), thinking about or planning suicide, or making an actual suicide attempt.

Major depressive disorder is considered episodic: its symptoms are typically present at their full magnitude for a certain period of time and then gradually abate. Approximately 50%–60% of people who experience an episode of major depressive disorder will have a second episode at some point in the future; those who have had two episodes have a 70% chance of having a third episode, and those who have had three episodes have a 90% chance of having a fourth episode (Rothschild, 1999). Although the episodes can last for months, a majority a people diagnosed with this condition (around 70%) recover within a year. However, a substantial number do not recover; around 12% show serious signs of impairment associated with major depressive disorder after 5 years (Boland & Keller, 2009). In the long-term, many who do recover will still show minor symptoms that fluctuate in their severity (Judd, 2012).

Results of Major Depressive Disorder

Major depressive disorder is a serious and incapacitating condition that can have a devastating effect on the quality of one’s life. The person suffering from this disorder lives a profoundly miserable existence that often results in unavailability for work or education, abandonment of promising careers, and lost wages; occasionally, the condition requires hospitalization. The majority of those with major depressive disorder report having faced some kind of discrimination, and many report that having received such treatment has stopped them from initiating close relationships, applying for jobs for which they are qualified, and applying for education or training (Lasalvia et al., 2013). Major depressive disorder also takes a toll on health. Depression is a risk factor for the development of heart disease in healthy patients, as well as adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with preexisting heart disease (Whooley, 2006).

Risk Factors for Major Depressive Disorder

Major depressive disorder is often referred to as the common cold of psychiatric disorders. Around 6.6% of the U.S. population experiences major depressive disorder each year; 16.9% will experience the disorder during their lifetime (Kessler & Wang, 2009). It is more common among women than among men, affecting approximately 20% of women and 13% of men at some point in their life (National Comorbidity Survey, 2007). The greater risk among women is not accounted for by a tendency to report symptoms or to seek help more readily, suggesting that gender differences in the rates of major depressive disorder may reflect biological and gender-related environmental experiences (Kessler, 2003).

Lifetime rates of major depressive disorder tend to be highest in North and South America, Europe, and Australia; they are considerably lower in Asian countries (Hasin, Fenton, & Weissman, 2011). The rates of major depressive disorder are higher among younger age cohorts than among older cohorts, perhaps because people in younger age cohorts are more willing to admit depression (Kessler & Wang, 2009).

A number of risk factors are associated with major depressive disorder: unemployment (including homemakers); earning less than $20,000 per year; living in urban areas; or being separated, divorced, or widowed (Hasin et al., 2011). Comorbid disorders include anxiety disorders and substance abuse disorders (Kessler & Wang, 2009).

Subtypes of Depression

The DSM-5 lists several different subtypes of depression. These subtypes—what the DSM-5 refer to as specifiers—are not specific disorders; rather, they are labels used to indicate specific patterns of symptoms or to specify certain periods of time in which the symptoms may be present. One subtype, seasonal pattern, applies to situations in which a person experiences the symptoms of major depressive disorder only during a particular time of year (e.g., fall or winter). In everyday language, people often refer to this subtype as the winter blues.

Another subtype, peripartum onset (commonly referred to as postpartum depression), applies to people who experience major depression during pregnancy or in the four weeks following the birth of their child (APA, 2013). These people often feel very anxious and may even have panic attacks. They may feel guilty, agitated, and be weepy. They may not want to hold or care for their newborn, even in cases in which the pregnancy was desired and intended. In extreme cases, the parent may have feelings of wanting to harm the child or themselves. In a horrific illustration, a woman named Andrea Yates, who suffered from extreme peripartum-onset depression (as well as other mental illnesses), drowned her five children in a bathtub (Roche, 2002). Most women with peripartum-onset depression do not physically harm their children, but most do have difficulty being adequate caregivers (Fields, 2010). A surprisingly high number of women experience symptoms of peripartum-onset depression. A study of 10,000 women who had recently given birth found that 14% screened positive for peripartum-onset depression, and that nearly 20% reported having thoughts of wanting to harm themselves (Wisner et al., 2013).

People with persistent depressive disorder (previously known as dysthymia) experience depressed moods most of the day nearly every day for at least two years, as well as at least two of the other symptoms of major depressive disorder. People with persistent depressive disorder are chronically sad and melancholy, but do not meet all the criteria for major depression. However, episodes of full-blown major depressive disorder can occur during persistent depressive disorder (APA, 2013).

Bipolar Disorder

A person with bipolar disorder (commonly known as manic depression) often experiences mood states that vacillate between depression and mania; that is, the person’s mood is said to alternate from one emotional extreme to the other (in contrast to unipolar, which indicates a persistently sad mood).

To be diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a person must have experienced a manic episode at least once in their life; although major depressive episodes are common in bipolar disorder, they are not required for a diagnosis (APA, 2013). According to the DSM-5, a manic episode is characterized as a “distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and abnormally and persistently increased activity or energy lasting at least one week,” that lasts most of the time each day (APA, 2013, p. 124). During a manic episode, some experience a mood that is almost euphoric and become excessively talkative, sometimes spontaneously starting conversations with strangers; others become excessively irritable and complain or make hostile comments. The person may talk loudly and rapidly, exhibiting flight of ideas, abruptly switching from one topic to another. These individuals are easily distracted, which can make a conversation very difficult. They may exhibit grandiosity, in which they experience inflated but unjustified self-esteem and self-confidence. For example, they might quit a job in order to “strike it rich” in the stock market, despite lacking the knowledge, experience, and capital for such an endeavour. They may take on several tasks at the same time (e.g., several time-consuming projects at work) and yet show little, if any, need for sleep; some may go for days without sleep. Patients may also recklessly engage in pleasurable activities that could have harmful consequences, including spending sprees, reckless driving, making foolish investments, excessive gambling, or engaging in sexual encounters with strangers (APA, 2013).

During a manic episode, individuals usually feel as though they are not ill and do not need treatment. However, the reckless behaviours that often accompany these episodes—which can be antisocial, illegal, or physically threatening to others—may require involuntary hospitalization (APA, 2013). Some patients with bipolar disorder will experience a rapid-cycling subtype, which is characterized by at least four manic episodes (or some combination of at least four manic and major depressive episodes) within one year.

Link to Learning

Watch ‘The Other Side of Me‘, in which Julie Kraft describes her lived experience with biopolar disorder.

Risk Factors for Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is considerably less frequent than major depressive disorder. In the United States, 1 out of every 167 people meets the criteria for bipolar disorder each year, and 1 out of 100 meet the criteria within their lifetime (Merikangas et al., 2011). The rates are higher in men than in women, and about half of those with this disorder report onset before the age of 25 (Merikangas et al., 2011). Around 90% of those with bipolar disorder have a comorbid disorder, most often an anxiety disorder or a substance abuse problem. Unfortunately, close to half of the people suffering from bipolar disorder do not receive treatment (Merikangas & Tohen, 2011). Suicide rates are extremely high among those with bipolar disorder: around 36% of individuals with this disorder attempt suicide at least once in their lifetime (Novick, Swartz, & Frank, 2010), and between 15%–19% complete suicide (Newman, 2004).

The Biological Basis of Mood Disorders

Mood disorders have been shown to have a strong genetic and biological basis. Relatives of those with major depressive disorder have double the risk of developing major depressive disorder, whereas relatives of patients with bipolar disorder have over nine times the risk (Merikangas et al., 2011). The rate of concordance for major depressive disorder is higher among identical twins than fraternal twins (50% vs. 38%, respectively), as is that of bipolar disorder (67% vs. 16%, respectively), suggesting that genetic factors play a stronger role in bipolar disorder than in major depressive disorder (Merikangas et al. 2011).

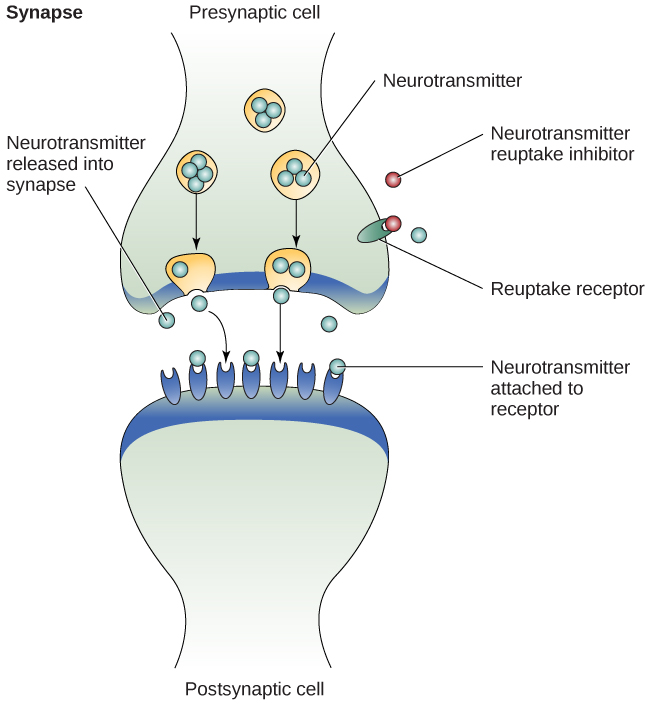

People with mood disorders often have imbalances in certain neurotransmitters, particularly norepinephrine and serotonin (Thase, 2009). These neurotransmitters are important regulators of the bodily functions that are disrupted in mood disorders, including appetite, sex drive, sleep, arousal, and mood. Medications that are used to treat major depressive disorder typically boost serotonin and norepinephrine activity, whereas lithium—used in the treatment of bipolar disorder—blocks norepinephrine activity at the synapses (Figure PY.15).

Since the 1950s, researchers have noted that depressed individuals have abnormal levels of cortisol, a stress hormone released into the blood by the neuroendocrine system during times of stress (Mackin & Young, 2004). When cortisol is released, the body initiates a fight-or-flight response in reaction to a threat or danger. Many people with depression show elevated cortisol levels (Holsboer & Ising, 2010), especially those reporting a history of early life trauma such as the loss of a parent or abuse during childhood (Baes, Tofoli, Martins, & Juruena, 2012). Such findings raise the question of whether high cortisol levels are a cause or a consequence of depression. High levels of cortisol are a risk factor for future depression (Halligan, Herbert, Goodyer, & Murray, 2007), and cortisol activates activity in the amygdala while deactivating activity in the PFC (McEwen, 2005)—both brain disturbances are connected to depression. Thus, high cortisol levels may have a causal effect on depression, as well as on its brain function abnormalities (van Praag, 2005). Also, because stress results in increased cortisol release (Michaud, Matheson, Kelly, Anisman, 2008), it is equally reasonable to assume that stress may precipitate depression.

A Diathesis-Stress Model and Major Depressive Disorders

Indeed, it has long been believed that stressful life events can trigger depression, and research has consistently supported this conclusion (Mazure, 1998). Stressful life events include significant losses, such as death of a loved one, divorce or separation, and serious health and money problems; life events such as these often precede the onset of depressive episodes (Brown & Harris, 1989). In particular, exit events—instances in which an important person departs (e.g., a death, divorce or separation, or a family member leaving home)—often occur prior to an episode (Paykel, 2003). Exit events are especially likely to trigger depression if these happenings occur in a way that humiliates or devalues the individual. For example, people who experience the breakup of a relationship initiated by the other person develop major depressive disorder at a rate more than 2 times that of people who experience the death of a loved one (Kendler, Hettema, Butera, Gardner, & Prescott, 2003).

Likewise, individuals who are exposed to traumatic stress during childhood—such as separation from a parent, family turmoil, and maltreatment (physical or sexual abuse)—are at a heightened risk of developing depression at any point in their lives (Kessler, 1997). A recent review of 16 studies involving over 23,000 subjects concluded that those who experience childhood maltreatment are more than 2 times as likely to develop recurring and persistent depression (Nanni, Uher, & Danese, 2012).

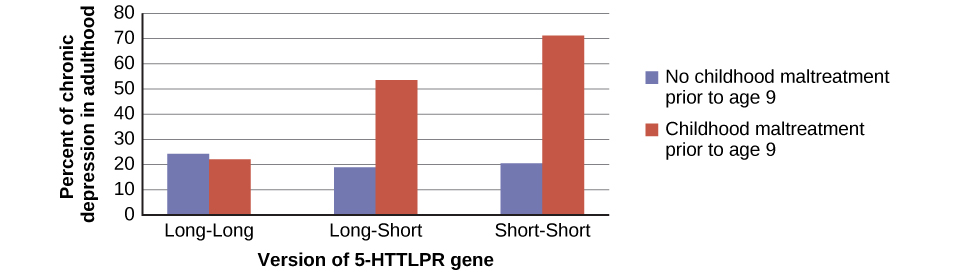

Of course, not everyone who experiences stressful life events or childhood adversities succumbs to depression—indeed, most do not. Clearly, a diathesis-stress interpretation of major depressive disorder, in which certain predispositions or vulnerability factors influence one’s reaction to stress, would seem logical. If so, what might such predispositions be? A study by Caspi and others (2003) suggests that an alteration in a specific gene that regulates serotonin (the 5-HTTLPR gene) might be one culprit. These investigators found that people who experienced several stressful life events were significantly more likely to experience episodes of major depression if they carried one or two short versions of this gene than if they carried two long versions. Those who carried one or two short versions of the 5-HTTLPR gene were unlikely to experience an episode, however, if they had experienced few or no stressful life events. Numerous studies have replicated these findings, including studies of people who experienced maltreatment during childhood (Goodman & Brand, 2009). In a recent investigation conducted in the United Kingdom (Brown & Harris, 2013), researchers found that childhood maltreatment before age 9 elevated the risk of chronic adult depression (a depression episode lasting for at least 12 months) among those individuals having one (LS) or two (SS) short versions of the 5-HTTLPR gene (Figure PY.17). Childhood maltreatment did not increase the risk for chronic depression for those have two long (LL) versions of this gene. Thus, genetic vulnerability may be one mechanism through which stress potentially leads to depression.

Cognitive Theories of Depression

Cognitive theories of depression take the view that depression is triggered by negative thoughts, interpretations, self-evaluations, and expectations (Joormann, 2009). These diathesis-stress models propose that depression is triggered by a “cognitive vulnerability” (negative and maladaptive thinking) and by precipitating stressful life events (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010). Perhaps the most well-known cognitive theory of depression was developed in the 1960s by psychiatrist Aaron Beck, based on clinical observations and supported by research (Beck, 2008). Beck theorized that depression-prone people possess depressive schemas, or mental predispositions to think about most things in a negative way (Beck, 1976). Depressive schemas contain themes of loss, failure, rejection, worthlessness, and inadequacy, and may develop early in childhood in response to adverse experiences, then remain dormant until they are activated by stressful or negative life events. Depressive schemas prompt dysfunctional and pessimistic thoughts about the self, the world, and the future. Beck believed that this dysfunctional style of thinking is maintained by cognitive biases, or errors in how we process information about ourselves, which lead us to focus on negative aspects of experiences, interpret things negatively, and block positive memories (Beck, 2008). A person whose depressive schema consists of a theme of rejection might be overly attentive to social cues of rejection (more likely to notice another’s frown), and he might interpret this cue as a sign of rejection and automatically remember past incidents of rejection. Longitudinal studies have supported Beck’s theory, in showing that a preexisting tendency to engage in this negative, self-defeating style of thinking—when combined with life stress—over time predicts the onset of depression (Dozois & Beck, 2008). Cognitive therapies for depression, aimed at changing a depressed person’s negative thinking, were developed as an expansion of this theory (Beck, 1976).

Another cognitive theory of depression, hopelessness theory, postulates that a particular style of negative thinking leads to a sense of hopelessness, which then leads to depression (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989). According to this theory, hopelessness is an expectation that unpleasant outcomes will occur or that desired outcomes will not occur, and there is nothing one can do to prevent such outcomes. A key assumption of this theory is that hopelessness stems from a tendency to perceive negative life events as having stable (“It’s never going to change”) and global (“It’s going to affect my whole life”) causes, in contrast to unstable (“It’s fixable”) and specific (“It applies only to this particular situation”) causes, especially if these negative life events occur in important life realms, such as relationships, academic achievement, and the like. Suppose a student who wishes to go to law school does poorly on an admissions test. If the student infers negative life events as having stable and global causes, she may believe that her poor performance has a stable and global cause (“I lack intelligence, and it’s going to prevent me from ever finding a meaningful career”), as opposed to an unstable and specific cause (“I was sick the day of the exam, so my low score was a fluke”). Hopelessness theory predicts that people who exhibit this cognitive style in response to undesirable life events will view such events as having negative implications for their future and self-worth, thereby increasing the likelihood of hopelessness—the primary cause of depression (Abramson et al., 1989). One study testing hopelessness theory measured the tendency to make negative inferences for bad life effects in participants who were experiencing uncontrollable stressors. Over the ensuing six months, those with scores reflecting high cognitive vulnerability were 7 times more likely to develop depression compared to those with lower scores (Kleim, Gonzalo, & Ehlers, 2011).

A third cognitive theory of depression focuses on how people’s thoughts about their distressed moods—depressed symptoms in particular—can increase the risk and duration of depression. This theory, which focuses on rumination in the development of depression, was first described in the late 1980s to explain the higher rates of depression in women than in men (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1987). Rumination is the repetitive and passive focus on the fact that one is depressed and dwelling on depressed symptoms, rather that distracting one’s self from the symptoms or attempting to address them in an active, problem-solving manner (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). When people ruminate, they have thoughts such as “Why am I so unmotivated? I just can’t get going. I’m never going to get my work done feeling this way” (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009, p. 393). Women are more likely than men to ruminate when they are sad or depressed (Butler & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1994), and the tendency to ruminate is associated with increases in depression symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999), heightened risk of major depressive episodes (Abela & Hankin, 2011), and chronicity of such episodes (Robinson & Alloy, 2003).