100 Approaches to Personality

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the behaviourist, cognitive, social cognitive, and humanist perspectives on personality

- Discuss the findings of the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart as they relate to personality and genetics

- Discuss temperament and describe the three infant temperaments identified by Thomas and Chess

- Discuss the evolutionary perspective on personality development

In contrast to the psychodynamic approaches of Freud and the neo-Freudians, which relate personality to inner (and hidden) processes, the learning approaches focus only on observable behaviour. This illustrates one significant advantage of the learning approaches over psychodynamics: Because learning approaches involve observable, measurable phenomena, they can be scientifically tested.

The Behavioural Perspective

Behaviourists do not believe in biological determinism: They do not see personality traits as inborn. Instead, they view personality as significantly shaped by the reinforcements and consequences outside of the organism. In other words, people behave in a consistent manner based on prior learning. B. F. Skinner, a strict behaviourist, believed that environment was solely responsible for all behaviour, including the enduring, consistent behaviour patterns studied by personality theorists.

As you may recall from your study on the psychology of learning, Skinner proposed that we demonstrate consistent behaviour patterns because we have developed certain response tendencies (Skinner, 1953). In other words, we learn to behave in particular ways. We increase the behaviours that lead to positive consequences, and we decrease the behaviours that lead to negative consequences. Skinner disagreed with Freud’s idea that personality is fixed in childhood. He argued that personality develops over our entire life, not only in the first few years. Our responses can change as we come across new situations; therefore, we can expect more variability over time in personality than Freud would anticipate. For example, consider a young adult, Jayden, a risk taker. Jayden drives fast and participates in dangerous sports such as hang gliding and kiteboarding. But after Jayden gets married and has children, the system of reinforcements and punishments in their environment changes. Speeding and extreme sports are no longer reinforced, so Jayden no longer engages in those behaviours. In fact, Jayden now describes themselves as a cautious person.

The Social-Cognitive Perspective

Albert Bandura agreed with Skinner that personality develops through learning. He disagreed, however, with Skinner’s strict behaviourist approach to personality development, because he felt that thinking and reasoning are important components of learning. He presented a social-cognitive theory of personality that emphasizes both learning and cognition as sources of individual differences in personality. In social-cognitive theory, the concepts of reciprocal determinism, observational learning, and self-efficacy all play a part in personality development.

Reciprocal Determinism

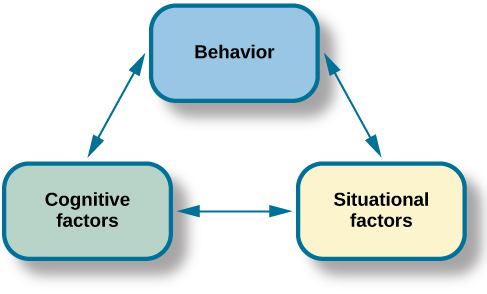

In contrast to Skinner’s idea that the environment alone determines behaviour, Bandura (1990) proposed the concept of reciprocal determinism, in which cognitive processes, behaviour, and context all interact, each factor influencing and being influenced by the others simultaneously (Figure P.11). Cognitive processes refer to all characteristics previously learned, including beliefs, expectations, and personality characteristics. Behaviour refers to anything that we do that may be rewarded or punished. Finally, the context in which the behaviour occurs refers to the environment or situation, which includes rewarding/punishing stimuli.

Observational Learning

Bandura’s key contribution to learning theory was the idea that much learning is vicarious. We learn by observing someone else’s behaviour and its consequences, which Bandura called observational learning. He felt that this type of learning also plays a part in the development of our personality. Just as we learn individual behaviours, we learn new behaviour patterns when we see them performed by other people or models. Drawing on the behaviourists’ ideas about reinforcement, Bandura suggested that whether we choose to imitate a model’s behaviour depends on whether we see the model reinforced or punished. Through observational learning, we come to learn what behaviours are acceptable and rewarded in our culture, and we also learn to inhibit deviant or socially unacceptable behaviours by seeing what behaviours are punished.

We can see the principles of reciprocal determinism at work in observational learning. For example, personal factors determine which behaviours in the environment a person chooses to imitate, and those environmental events in turn are processed cognitively according to other personal factors. One person may experience receiving attention as reinforcing, and that person may be more inclined to imitate behaviours such as boasting when a model has been reinforced. For others, boasting may be viewed negatively, despite the attention that might result—or receiving heightened attention may be perceived as being scrutinized. In either case, the person may be less likely to imitate those behaviours even though the reasons for not doing so would be different.

Self-Efficacy

Bandura (1977, 1995) has studied a number of cognitive and personal factors that affect learning and personality development, and most recently has focused on the concept of self-efficacy. Self-efficacyis our level of confidence in our own abilities, developed through our social experiences. Self-efficacy affects how we approach challenges and reach goals. In observational learning, self-efficacy is a cognitive factor that affects which behaviours we choose to imitate as well as our success in performing those behaviours.

People who have high self-efficacy believe that their goals are within reach, have a positive view of challenges seeing them as tasks to be mastered, develop a deep interest in and strong commitment to the activities in which they are involved, and quickly recover from setbacks. Conversely, people with low self-efficacy avoid challenging tasks because they doubt their ability to be successful, tend to focus on failure and negative outcomes, and lose confidence in their abilities if they experience setbacks. Feelings of self-efficacy can be specific to certain situations. For instance, a student might feel confident in their ability in English class but much less so in math class.

Julian Rotter and Locus of Control

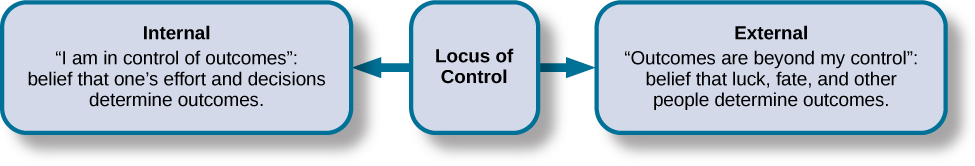

Julian Rotter (1966) proposed the concept of locus of control, another cognitive factor that affects learning and personality development. Distinct from self-efficacy, which involves our belief in our own abilities, locus of control refers to our beliefs about the power we have over our lives. In Rotter’s view, people possess either an internal or an external locus of control (Figure P.12). Those of us with an internal locus of control (“internals”) tend to believe that most of our outcomes are the direct result of our efforts. Those of us with an external locus of control (“externals”) tend to believe that our outcomes are outside of our control. Externals see their lives as being controlled by other people, luck, or chance. For example, say you didn’t spend much time studying for your psychology test and went out to dinner with friends instead. When you receive your test score, you see that you earned a D. If you possess an internal locus of control, you would most likely admit that you failed because you didn’t spend enough time studying and decide to study more for the next test. On the other hand, if you possess an external locus of control, you might conclude that the test was too hard and not bother studying for the next test, because you figure you will fail it anyway. Researchers have found that people with an internal locus of control perform better academically, achieve more in their careers, are more independent, are healthier, are better able to cope, and are less depressed than people who have an external locus of control (Benassi, Sweeney, & Durfour, 1988; Lefcourt, 1982; Maltby, Day, & Macaskill, 2007; Whyte, 1977, 1978, 1980).

Link to Learning

Take the Locus of Control questionnaire, to learn more. Scores range from 0 to 13. A low score on this questionnaire indicates an internal locus of control, and a high score indicates an external locus of control.

Walter Mischel and the Person-Situation Debate

Walter Mischel was a student of Julian Rotter and taught for years at Stanford, where he was a colleague of Albert Bandura. Mischel surveyed several decades of empirical psychological literature regarding trait prediction of behaviour, and his conclusion shook the foundations of personality psychology. Mischel found that the data did not support the central principle of the field—that a person’s personality traits are consistent across situations. His report triggered a decades-long period of self-examination, known as the person-situation debate, among personality psychologists.

Mischel suggested that perhaps we were looking for consistency in the wrong places. He found that although behaviour was inconsistent across different situations, it was much more consistent within situations—so that a person’s behaviour in one situation would likely be repeated in a similar one. And as you will see next regarding his famous “marshmallow test,” Mischel also found that behaviour is consistent in equivalent situations across time.

One of Mischel’s most notable contributions to personality psychology was his ideas on self-regulation. According to Lecci & Magnavita (2013), “Self-regulation is the process of identifying a goal or set of goals and, in pursuing these goals, using both internal (e.g., thoughts and affect) and external (e.g., responses of anything or anyone in the environment) feedback to maximize goal attainment” (p. 6.3). Self-regulation is also known as will power. When we talk about will power, we tend to think of it as the ability to delay gratification. For example, Addison’s teenage child made strawberry cupcakes, and they looked delicious. However, Addison forfeited the pleasure of eating one, because Addison is training for a 5K race and wants to be fit and do well in the race. Would you be able to resist getting a small reward now in order to get a larger reward later? This is the question Mischel investigated in his now-classic marshmallow test.

Mischel designed a study to assess self-regulation in young children. In the marshmallow study, Mischel and his colleagues placed a preschool child in a room with one marshmallow on the table. The children were told they could either eat the marshmallow now, or wait until the researcher returned to the room, and then they could have two marshmallows (Mischel, Ebbesen & Raskoff, 1972). This was repeated with hundreds of preschoolers. What Mischel and his team found was that young children differ in their degree of self-control. Mischel and his colleagues continued to follow this group of preschoolers through high school, and what do you think they discovered? The children who had more self-control in preschool (the ones who waited for the bigger reward) were more successful in high school. They had higher SAT scores, had positive peer relationships, and were less likely to have substance abuse issues; as adults, they also had more stable marriages (Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989; Mischel et al., 2010). On the other hand, those children who had poor self-control in preschool (the ones who grabbed the one marshmallow) were not as successful in high school, and they were found to have academic and behavioural problems. A more recent study using a larger and more representative sample found associations between early delay of gratification (Watts, Duncan, & Quan, 2018) and measures of achievement in adolescence. However, researchers also found that the associations were not as strong as those reported during Mischel’s initial experiment and were quite sensitive to situational factors such as early measures of cognitive capacity, family background, and home environment. This research suggests that consideration of situational factors is important to better understand behaviour.

Link to Learning

Watch Joachim de Posada’s TED Talk about the marshmallow test, to learn more and to see some footage of children taking the test.

Today, the debate is mostly resolved, and most psychologists consider both the situation and personal factors in understanding behaviour. For Mischel (1993), people are situation processors. The children in the marshmallow test each processed, or interpreted, the rewards structure of that situation in their own way. Mischel’s approach to personality stresses the importance of both the situation and the way the person perceives the situation. Instead of behaviour being determined by the situation, people use cognitive processes to interpret the situation and then behave in accordance with that interpretation.

Humanism

As the “third force” in psychology, humanism is touted as a reaction both to the pessimistic determinism of psychoanalysis, with its emphasis on psychological disturbance, and to the behaviourists’ view of humans passively reacting to the environment, which has been criticized as making people out to be personality-less robots. It does not suggest that psychoanalytic, behaviourist, and other points of view are incorrect but argues that these perspectives do not recognize the depth and meaning of human experience, and fail to recognize the innate capacity for self-directed change and transforming personal experiences. This perspective focuses on how healthy people develop.

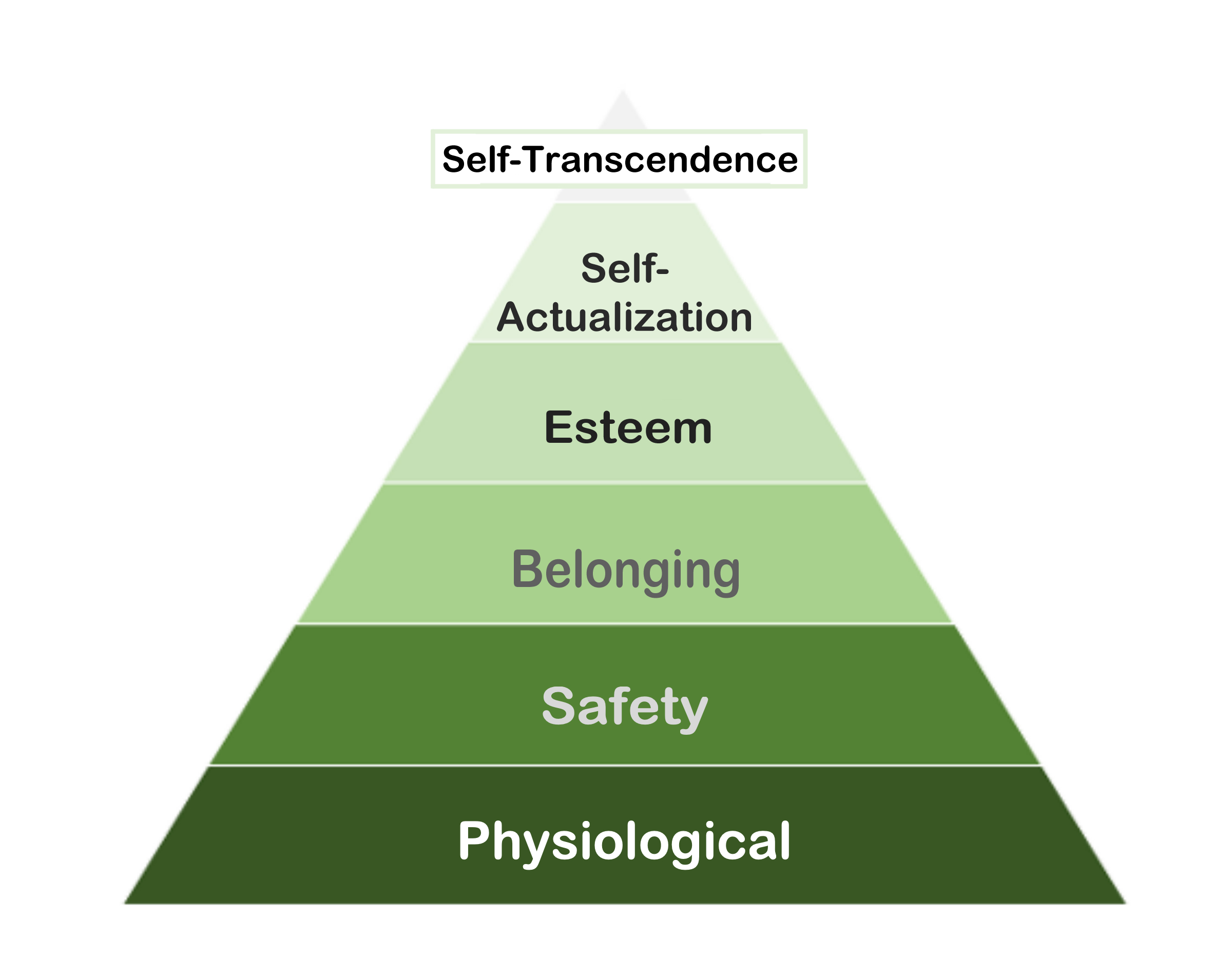

One pioneering humanist, Abraham Maslow, studied people who he considered to be healthy, creative, and productive, including Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and others. Maslow (1950, 1970) found that such people share similar characteristics, such as being open, creative, loving, spontaneous, compassionate, concerned for others, and accepting of themselves. When you studied motivation, you learned about one of the best-known humanistic theories, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory (Figure P.13), in which Maslow proposes that human beings have certain needs in common and that these needs must be met in a certain order. The highest need is the need for self-actualization, which is the achievement of our fullest potential. Maslow differentiated between needs that motivate us to fulfill something that is missing and needs that inspire us to grow. He believed that many emotional and behavioural concerns arise as a result of failing to meet these hierarchical needs.

Carl Rogers (1902–1987) was also an American psychologist who, like Maslow, emphasized the potential for good that exists within all people (Figure P.14). Rogers used a therapeutic technique known as client-centred therapy in helping his clients deal with problematic issues that resulted in their seeking psychotherapy. Unlike a psychoanalytic approach in which the therapist plays an important role in interpreting what conscious behaviour reveals about the unconscious mind, client-centred therapy involves the patient taking a lead role in the therapy session. Rogers believed that a therapist needed to display three features to maximize the effectiveness of this particular approach: unconditional positive regard, genuineness, and empathy. Unconditional positive regard refers to the fact that the therapist accepts their client for who they are, no matter what the patient might say. Provided these factors, Rogers believed that people were more than capable of dealing with and working through their own issues (Thorne & Henley, 2005).

Biological Approach

How much of our personality is in-born and biological, and how much is influenced by the environment and culture we are raised in? Psychologists who favour the biological approach believe that inherited predispositions as well as physiological processes can be used to explain differences in our personalities (Burger, 2008).

Evolutionary psychology relative to personality development looks at personality traits that are universal, as well as differences across individuals. In this view, adaptive differences have evolved and then provide a survival and reproductive advantage. Individual differences are important from an evolutionary viewpoint for several reasons. Certain individual differences, and the heritability of these characteristics, have been well documented. David Buss has identified several theories to explore this relationship between personality traits and evolution, such as life-history theory, which looks at how people expend their time and energy (such as on bodily growth and maintenance, reproduction, or parenting). Another example is costly signalling theory, which examines the honesty and deception in the signals people send one another about their quality as a mate or friend (Buss, 2009).

In the field of behavioural genetics, the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart—a well-known study of the genetic basis for personality—conducted research with twins from 1979 to 1999. In studying 350 pairs of twins, including pairs of identical and fraternal twins reared together and apart, researchers found that identical twins, whether raised together or apart, have very similar personalities (Bouchard, 1994; Bouchard, Lykken, McGue, Segal, & Tellegen, 1990; Segal, 2012). These findings suggest the heritability of some personality traits. Heritability refers to the proportion of difference among people that is attributed to genetics. Some of the traits that the study reported as having more than a 0.50 heritability ratio include leadership, obedience to authority, a sense of well-being, alienation, resistance to stress, and fearfulness. The implication is that some aspects of our personalities are largely controlled by genetics; however, it’s important to point out that traits are not determined by a single gene, but by a combination of many genes, as well as by epigenetic factors that control whether the genes are expressed.

Other research that has examined the link between personality and other factors has identified and studied Type A and Type B personalities, which you will learn more about in the chapter on Stress, Health, and Lifestyle.

Link to Learning

Watch this video about the influence of genes on personality, to learn more.

Temperament

Most contemporary psychologists believe temperament has a biological basis due to its appearance very early in our lives (Rothbart, 2011). As you learned when you studied lifespan development, Thomas and Chess (1977) found that babies could be categorized into one of three temperaments: easy, difficult, or slow to warm up. However, environmental factors (family interactions, for example) and maturation can affect the ways in which children’s personalities are expressed (Carter et al., 2008).

Research suggests that there are two dimensions of our temperament that are important parts of our adult personality—reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart, Ahadi, & Evans, 2000). Reactivity refers to how we respond to new or challenging environmental stimuli; self-regulation refers to our ability to control that response (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981; Rothbart, Sheese, Rueda, & Posner, 2011). For example, one person may immediately respond to new stimuli with a high level of anxiety, while another barely notices it.