52 Forgetting and Memory Errors

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Compare and contrast different types of amnesia

- Discuss factors that affect the reliability of eyewitness testimony

- Discuss encoding failure

- Discuss the various memory errors

- Compare and contrast the different types of interference

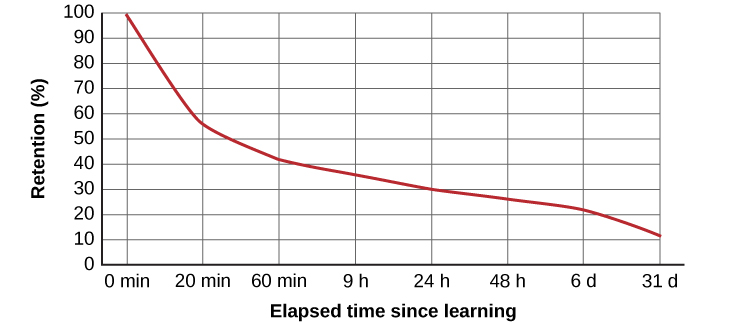

“I’ve a grand memory for forgetting,” quipped author Robert Louis Stevenson. Forgetting refers to loss of information from long-term memory. In 1885, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus studied forgetting by memorizing lists of nonsense syllables and measuring how many words he remembered when he attempted to relearn each list. He compared memory performance over different delay periods, from 20 minutes to 30 days later. The result is his famous forgetting curve (Figure M.14) showing that information fades with the passage of time. An average person will lose 50% of the memorized information after 20 minutes and 70% after 24 hours (Ebbinghaus, 1885-1964). Memory for new information decays quickly and then eventually levels out. But why do we forget? To answer this question, we will look at several perspectives on forgetting.

Schacter and the Seven Sins of Memory

There are many theories explaining different types of memory, but there aren’t as many theories about types of forgetting. Memory researcher Daniel Schacter attempted to organize memory errors into a unified framework in his book, The Seven Sins of Memory (2001). Schacter presents these as a list of seven “sins,” falling into one of two categories: errors of omission, involving failures of recall, and errors of commission, where recall is distorted or unwanted (Table M.1).

| Table M.1 Schacter’s Seven Sins of Memory | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sin | Type | Description | Example |

| Transience | Forgetting | Accessibility of memory decreases over time | Forget events that occurred long ago |

| absentmindedness | Forgetting | Forgetting caused by lapses in attention | Forget where your phone is |

| Blocking | Forgetting | Accessibility of information is temporarily blocked | Tip of the tongue |

| Misattribution | Distortion | Source of memory is confused | Recalling a dream memory as a waking memory |

| Suggestibility | Distortion | False memories | Result from leading questions |

| Bias | Distortion | Memories distorted by current belief system | Align memories to current beliefs |

| Persistence | Intrusion | Inability to forget undesirable memories | Traumatic events |

Let’s look at the first sin: transience, which means that memories can fade over time, as demonstrated by Ebbinghaus’ forgetting curve for nonsense syllables (Figure M.13). Information that’s stored but not used is vulnerable to this type of forgetting. Consider this real life example: Nathan’s English teacher has assigned students to read the novel To Kill a Mockingbird. He tells his mom he has to read this book for class and she says, “Oh, I loved that book!” Nathan asks her what the book is about, and after some hesitation she says, “Well, I know I read the book in high school, and I remember that one of the main characters is named Scout, and her father is an lawyer, but I honestly don’t remember anything else.” Nathan wonders if his mother actually read the book, and his mother is surprised she can’t recall the plot. What is going on here is storage decay: unused information tends to fade with the passage of time.

Are you constantly losing your phone? Have you ever returned home to make sure you locked the door? Have you ever walked into a room for something but forgotten what it was? You probably answered yes to at least one, if not all, these examples—but don’t worry, you are not alone. We are all prone to committing the memory error known as absentmindedness, which describes lapses in memory caused by breaks in attention or our focus being elsewhere. Insufficient attention when we are first learning something can result in encoding failure. We can’t remember something if we never stored it in our memory in the first place. For some types of information, we use effortful encoding in order to remember something, where we pay attention to the details and actively work to process the information. However, many times we don’t do this. Think of how many times in your life you’ve seen a Canadian one-dollar coin. Can you accurately recall what the front of a Loonie looks like? Can you sketch it accurately? Probably not and the most likely reason is due to an encoding failure. Most of us never encode the details of the coin, we only encode enough information to be able to distinguish it from other coins. If we don’t encode the information, then it’s not in our long-term memory, so we will not be able to remember it.

Schachter’s third sin of omission is blocking: an inability to access stored information. “I just streamed this movie called Oblivion, and it had that famous actor in it. Oh, what’s his name? He’s been in all of those movies, like The Shawshank Redemption and The Dark Knight trilogy. I think he’s even won an Oscar. Oh gosh, I can picture his face in my mind, and hear his distinctive voice, but I just can’t think of his name! This is going to bother me until I can remember it!” This particular error can be so frustrating because you have the information right on the tip of your tongue. (Figure M.15).

Now let’s take a look at the errors of commission: misattribution happens when you confuse the source of your information. Let’s say Alejandra was dating Lucia and they saw the first Hobbit movie together. Then they broke up and Alejandra saw the second Hobbit movie with someone else. Later that year, Alejandra and Lucia get back together. One day, they are discussing how the Hobbit books and movies are different and Alejandra says to Lucia, “I loved watching the second movie with you and seeing you jump out of your seat during that super scary part.” When Lucia responded with a puzzled look, Alejandra realized she’d committed the error of misattribution.

Schachter’s second error of commission is suggestibility, when inaccurate information is incorporated into the memory during recall. This is similar to misattribution, since it also involves memory distortion, however with misattribution you create a false memory entirely on your own, while with suggestibility, it comes from outside the individual. From time to time, we’re all vulnerable to the power of suggestion, in fact the way a question is asked can alter the memory of the requested information. For example, imagine you are in elementary school and you just witnessed a fight outside between two of your male classmates. After hearing of the incident, a teacher asks you questions such as: “How hard did he hit him? Who swung first? Did either of them try to run away?” Notice the use of descriptive language as the teacher is asking the student questions. This is important as descriptive language can influence the way in which memories are recalled.

Bias is when our current beliefs distort memory of past events. There are several types of bias:

- Stereotypical bias involves racial and gender biases. For example, when Asian American and European American research participants were presented with a list of names, they more frequently incorrectly remembered typical African American names such as Jamal and Tyrone to be associated with the occupation basketball player, and they more frequently incorrectly remembered typical Caucasian names such as Greg and Howard to be associated with the occupation of politician (Payne, Jacoby, & Lambert, 2004).

- Egocentric bias involves enhancing our memories of the past (Payne et al., 2004). Imagine you are playing in the final game of the national championship with your soccer team. The score is tied up with only a minute left on the clock. You have the ball and are running down the wing, taking a shot outside the box and you score the goal, top-corner. After the game you brag about your game-winning shot to your brother who wasn’t at the game, and he says: “Huh? My friend told me it was actually a lucky goal as it deflected off a player and the wind caught it.” This is an example of egocentric bias since the individual who scored enhanced the memory of the goal compared to the reality of the goal.

- Hindsight bias happens when we think an outcome was inevitable after the fact. This is the “I knew it all along” phenomenon. The reconstructive nature of memory contributes to hindsight bias (Carli, 1999). We remember untrue events that seem to confirm that we knew the outcome all along. An experiment by Fischhoff and Beyth (1975) asked participants to estimate the probabilities of outcomes occurring prior to Richard Nixon’s trip to China and the U.S.S.R. in 1972. Later, participants were asked to complete the same questionnaire remembering the probability they had given while also answering whether the outcome in question had occurred or not. They found that following events, participants were rarely surprised by the outcomes which they reported had occurred and that this effect was larger the more time had passed. Studies such as this demonstrate how we tend to overestimate our ability to make predictions about whether given events will occur.

Have you ever had a song play over and over in your head? How about a memory of a traumatic event, something you really do not want to think about? When you keep remembering something, to the point where you can’t “get it out of your head” and it interferes with your ability to concentrate on other things, it is called persistence, Schacter’s seventh and last memory error. It’s a failure of our memory system because we involuntarily recall unwanted memories, particularly unpleasant ones (Figure M.16). For instance, you witness a horrific car accident on the way to work one morning, and you can’t concentrate on work because you keep remembering the scene.

Memory Construction and Reconstruction

The formulation of new memories is sometimes called construction, and the process of bringing up old memories is called reconstruction. Yet as we retrieve our memories, we also tend to alter and modify them. A memory pulled from long-term storage into short-term memory is flexible. New events can be added, and we can change what we think we remember about past events, resulting in inaccuracies and distortions. People may not intend to distort facts, but it can happen in the process of retrieving old memories and combining them with new memories (Roediger & DeSoto, 2015).

Eyewitness Testimony

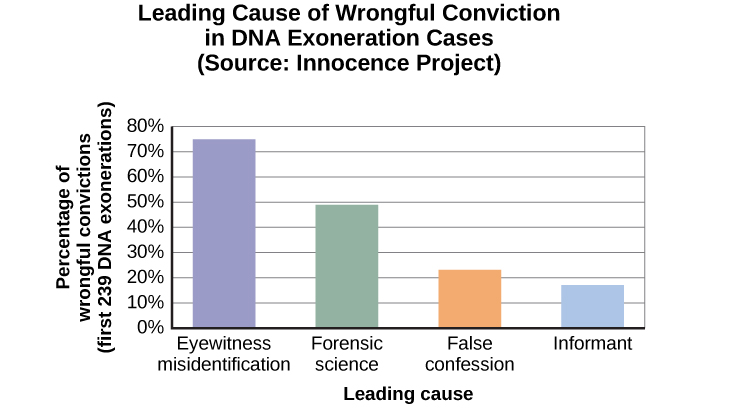

Police officers, prosecutors, and the courts often rely on eyewitness identification and testimony in the prosecution of criminals. However, faulty eyewitness identification and testimony can lead to wrongful convictions (Figure M.17).

Dig Deeper

Preserving Eyewitness Memory: The Elizabeth Smart Case

When Elizabeth Smart was 14 years old and fast asleep in her bed at home, she was abducted at knifepoint. Her nine-year-old sister, Mary Katherine, was sleeping in the same bed and watched, terrified, as her beloved older sister was abducted. Mary Katherine was the sole eyewitness to this crime and was very fearful. In the coming weeks, the Salt Lake City police and the FBI proceeded with caution with Mary Katherine. They did not want to implant any false memories or mislead her in any way. They did not show her police line-ups or push her to do a composite sketch of the abductor. They knew if they corrupted her memory, Elizabeth might never be found. For several months, there was little or no progress on the case. Then, about 4 months after the kidnapping, Mary Katherine first recalled that she had heard the abductor’s voice prior to that night (he had worked exactly one day as a handyman at the family’s home) and then she was able to name the person whose voice it was. The family contacted the press and others recognized him—after a total of nine months, the suspect was caught and Elizabeth Smart was returned to her family.

The Misinformation Effect

Cognitive psychologist Elizabeth Loftus has conducted extensive research on memory. She has studied false memories and developed the misinformation effect paradigm, which holds that after exposure to additional and possibly inaccurate information, a person may misremember the original event.

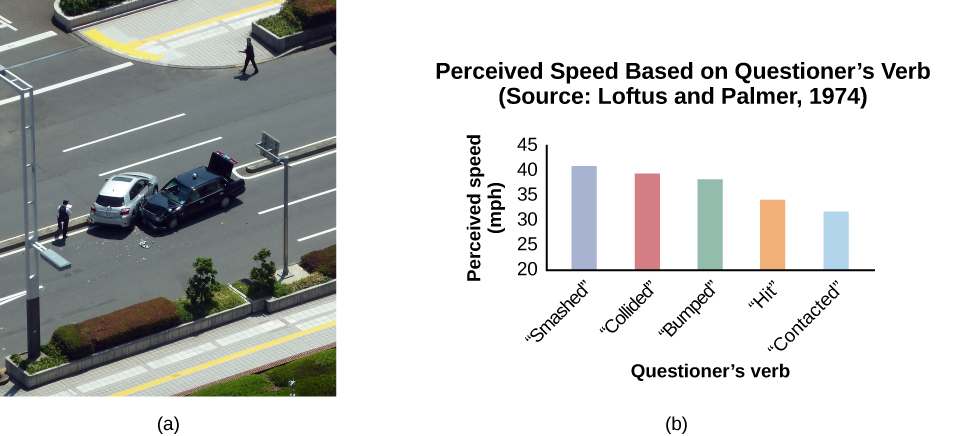

According to Loftus, an eyewitness’s memory of an event is very flexible due to the misinformation effect. To test this theory, Loftus and John Palmer (1974) asked 45 U.S. college students to estimate the speed of cars using different forms of questions (Figure M.18). The participants were shown films of car accidents and were asked to play the role of the eyewitness and describe what happened. They were asked, “About how fast were the cars going when they (smashed, collided, bumped, hit, contacted) each other?” The participants estimated the speed of the cars based on the verb used.

Participants who heard the word “smashed” estimated that the cars were traveling at a much higher speed than participants who heard the word “contacted.” The implied information about speed, based on the verb they heard, had an effect on the participants’ memory of the accident. In a follow-up one week later, participants were asked if they saw any broken glass (none was shown in the accident pictures). Participants who had been in the “smashed” group were more than twice as likely to indicate that they did remember seeing glass. Loftus and Palmer demonstrated that a leading question encouraged them to not only remember the cars were going faster, but to also falsely remember that they saw broken glass.

False memories like these can be influenced by question wording without us even realizing it. For instance,”What shade of pink was the dress in the window?” presupposes that there was a dress in the window AND it was pink. When asked a retrieval question like this, one’s memory is biased towards these “facts.”

Ever since Loftus published her first studies on the suggestibility of eyewitness testimony in the 1970s, social scientists, police officers, therapists, and legal practitioners have been aware of the flaws in interview practices. Consequently, steps have been taken to decrease suggestibility of witnesses. One way is to modify how witnesses are questioned. When interviewers use neutral and less leading language, children more accurately recall what happened and who was involved (Goodman, 2006; Pipe, 1996; Pipe, Lamb, Orbach, & Esplin, 2004). Another change is in how police lineups are conducted. It’s recommended that a blind photo lineup be used. This way the person administering the lineup doesn’t know which photo belongs to the suspect, minimizing the possibility of giving leading cues. Additionally, judges in some American states now inform jurors about the possibility of misidentification. Judges can also suppress eyewitness testimony if they deem it unreliable.

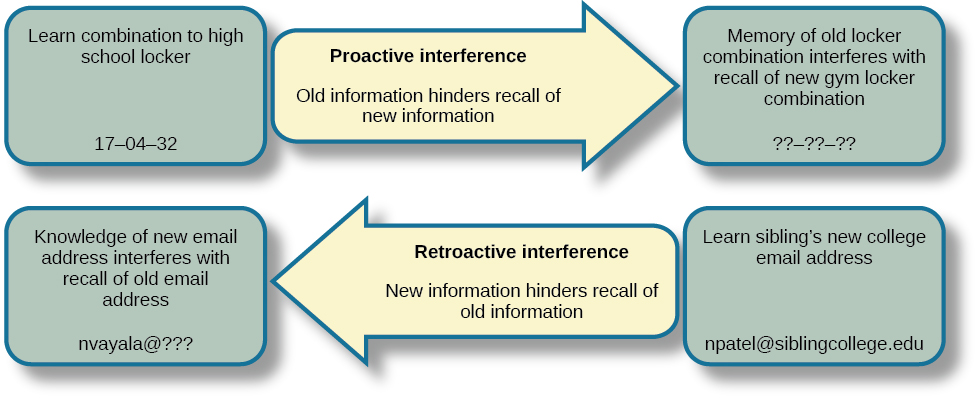

Interference

Sometimes information is stored in our memory but for some reason it is inaccessible. This is known as interference and there are two types: proactive interference and retroactive interference (Figure M.19). Have you ever gotten a new phone number or moved to a new address but yet continue to give people the old (and wrong) phone number or address? When the new year starts do you find you accidentally write the previous year? These are examples of proactive interference: when old information hinders the recall of newly learned information. Retroactive interference happens when information learned more recently hinders the recall of older information. For example, this week you are studying about memory and learn about the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve. Next week you study lifespan development and learn about Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development but thereafter have trouble remembering Ebbinghaus’s work because you can only remember Erickson’s theory.

Amnesia

Amnesia is the loss of long-term memory that occurs as the result of disease, injury, or trauma. Endel Tulving (2002) and his colleagues at the University of Toronto studied patient K.C., who suffered a traumatic head injury in a motorcycle accident. Tulving writes:

“The outstanding fact about K.C.’s mental make-up is his utter inability to remember any events, circumstances, or situations from his own life. His episodic amnesia covers his whole life, from birth to the present. The only exception is the experiences that, at any time, he has had in the last minute or two.” (Tulving, 2002, p. 14)

The first type of amnesia is anterograde amnesia (Figure M.20), which refers to the inability to remember new information, although you can remember information and events that happened prior to your injury. Many people with this form of amnesia are unable to form new episodic or semantic memories but are still able to form new procedural (remember implicit) memories (Bayley & Squire, 2002). This was true of patient H.M. as the brain damage caused by his surgery resulted in anterograde amnesia. H.M. would read the same magazine over and over, having no memory of ever reading it—it was always new to him. He also could not remember people he had met after his surgery. If you were introduced to H.M. and then you left the room for a few minutes, he would not know you upon your return and would introduce himself to you again. However, when presented the same puzzle several days in a row, although he did not remember having seen the puzzle before, his speed at solving it became faster each day (because of relearning) (Corkin, 1965; 1968).

Retrograde amnesia is loss of memory for events that occurred prior to the trauma. People with retrograde amnesia often have difficulty remembering their past episodic memories. What if you woke up in the hospital one day and there were people surrounding your bed claiming to be your spouse, your children, and your parents but you don’t recognize any of them? You were in a car accident, suffered a head injury, and now have retrograde amnesia and don’t remember anything about your life before waking up in the hospital. Hollywood has been fascinated with the amnesia plot for nearly a century, going all the way back to the film Garden of Lies from 1915 to more recent movies such as the Jason Bourne spy thrillers. However, for real-life sufferers of retrograde amnesia, like former NFL football player Scott Bolzan, the story is not a Hollywood movie. Bolzan fell, hit his head, and deleted 46 years of his life in an instant. He is now living with one of the most extreme cases of retrograde amnesia on record.

Link to Learning

Watch this story about Scott Bolzan’s amnesia and his attempts to get his life back, to learn more.