61 Classical Conditioning

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how classical conditioning occurs

- Summarize the processes of acquisition, extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalization, and discrimination

Does the name Ivan Pavlov ring a bell? Even if you are new to the study of psychology, chances are that you have heard of Pavlov and his famous dogs.

Pavlov (1849–1936), a Russian scientist, performed extensive research on dogs and is best known for his experiments in classical conditioning (Figure L.3). As we discussed briefly in the previous section, classical conditioning is a process by which we learn to associate stimuli and, consequently, to anticipate events.

Pavlov came to his conclusions about how learning occurs completely by accident. Pavlov was a physiologist, not a psychologist. Physiologists study the life processes of organisms, from the molecular level to the level of cells, organ systems, and entire organisms. Pavlov’s area of interest was the digestive system (Hunt, 2007). In his studies with dogs, Pavlov measured the amount of saliva produced in response to various foods. Over time, Pavlov (1927) observed that the dogs began to salivate not only at the taste of food, but also at the sight of food, at the sight of an empty food bowl, and even at the sound of the laboratory assistants’ footsteps. Salivating to food in the mouth is reflexive, so no learning is involved. However, dogs don’t naturally salivate at the sight of an empty bowl or the sound of footsteps.

These unusual responses intrigued Pavlov, and he wondered what accounted for what he called the dogs’ “psychic secretions” (Pavlov, 1927). To explore this phenomenon in an objective manner, Pavlov designed a series of carefully controlled experiments to see which stimuli would cause the dogs to salivate. He was able to train the dogs to salivate in response to stimuli that clearly had nothing to do with food, such as the sound of a bell, a light, and a touch on the leg. Through his experiments, Pavlov realized that an organism has two types of responses to its environment: (1) unconditioned (unlearned) responses, or reflexes, and (2) conditioned (learned) responses.

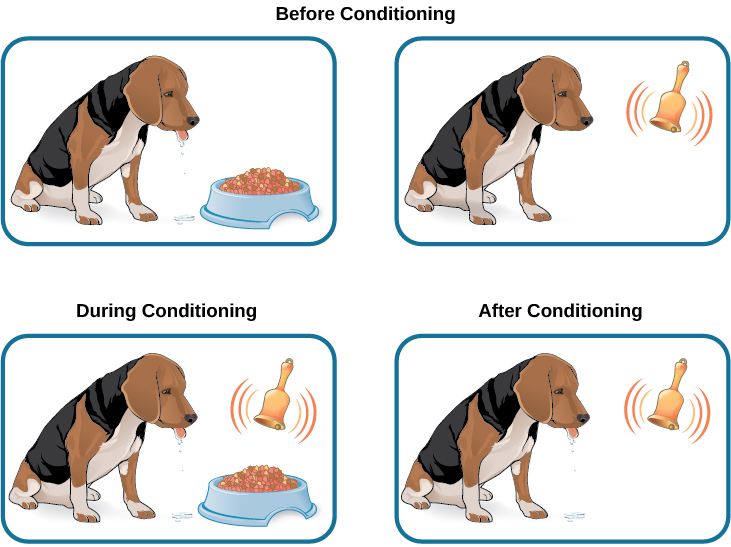

In Pavlov’s experiments, the dogs salivated each time meat powder was presented to them. The meat powder in this situation was an unconditioned stimulus (US): a stimulus that elicits a reflexive response in an organism. The dogs’ salivation was an unconditioned response (UCR): a natural (unlearned) reaction to a given stimulus. Before conditioning, think of the dogs’ stimulus and response like this:

In classical conditioning, a neutral stimulus is presented immediately before an unconditioned stimulus. Pavlov would sound a tone (like ringing a bell) and then give the dogs the meat powder (Figure L.4). The tone was the neutral stimulus (NS), which is a stimulus that does not naturally elicit a response. Prior to conditioning, the dogs did not salivate when they just heard the tone because the tone had no association for the dogs.

Tone (NS) + Meat Powder (US) → Salivation (UCR)

When Pavlov paired the tone with the meat powder over and over again, the previously neutral stimulus (the tone) also began to elicit salivation from the dogs. Thus, the neutral stimulus became the conditioned stimulus (CS), which is a stimulus that elicits a response after repeatedly being paired with an unconditioned stimulus. Eventually, the dogs began to salivate to the tone alone, just as they previously had salivated at the sound of the assistants’ footsteps. The behaviour caused by the conditioned stimulus is called the conditioned response (CR). In the case of Pavlov’s dogs, they had learned to associate the tone (CS) with being fed, and they began to salivate (CR) in anticipation of food.

TRICKY TOPIC: CLASSICAL CONDITIONING

For a full transcript of this video, click here

Link to Learning

View this video about Pavlov and his dogs to learn more.

Real World Application of Classical Conditioning

How does classical conditioning work in the real world? Consider the case of Farah, who was diagnosed with cancer. When Farah received their first chemotherapy treatment, they vomited shortly after the chemicals were injected. In fact, every trip to the doctor for chemotherapy treatment shortly after the drugs were injected, Farah vomited. Farah’s treatment was a success and their cancer went into remission. Now, when Farah visits their oncologist’s office every 6 months for a check-up, they become nauseous. In this case, the chemotherapy drugs are the unconditioned stimulus (US), vomiting is the unconditioned response (UCR), the doctor’s office is the conditioned stimulus (CS) after being paired with the US, and nausea is the conditioned response (CR). Let’s assume that the chemotherapy drugs that Farah takes are given through a syringe injection. After entering the doctor’s office, Farah sees a syringe, and then gets their medication. In addition to the doctor’s office, Farah will learn to associate the syringe will the medication and will respond to syringes with nausea. This is an example of higher-order (or second-order) conditioning, when the conditioned stimulus (the doctor’s office) serves to condition another stimulus (the syringe). It is hard to achieve anything above second-order conditioning. For example, if someone rang a bell every time Farah received a syringe injection of chemotherapy drugs in the doctor’s office, Farah likely will never get sick in response to the bell.

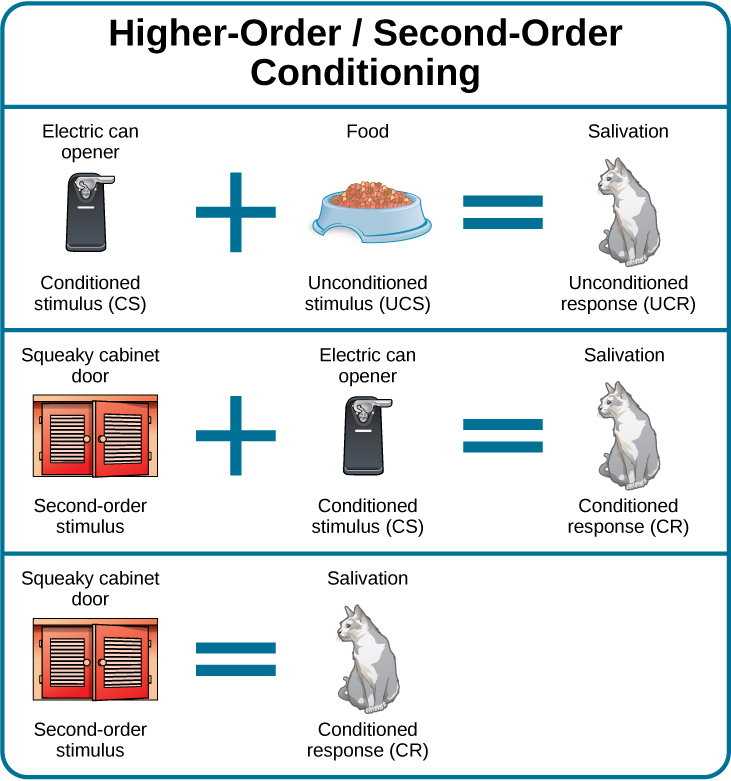

Consider another example of classical conditioning. Let’s say you have a cat named Zelda, who is quite spoiled. You keep Zelda’s food in a separate cabinet, and you also have a special electric can opener that you use only to open cans of cat food. For every meal, Zelda hears the distinctive sound of the electric can opener (“zzhzhz”) and then gets their food. Zelda quickly learns that when they hear “zzhzhz” that means it’s feeding time. What do you think Zelda does when they hear the electric can opener? Zelda will likely get excited and run to where you are preparing their food. This is an example of classical conditioning. In this case, what are the US, CS, UCR, and CR?

What if the cabinet holding Zelda’s food becomes squeaky? In that case, Zelda hears “squeak” (the cabinet), “zzhzhz” (the electric can opener), and then they get the food. Zelda will learn to get excited when they hear the “squeak” of the cabinet. Pairing a new neutral stimulus (“squeak”) with the conditioned stimulus (“zzhzhz”) is called higher-order conditioning, orsecond-order conditioning. This means you are using the conditioned stimulus of the can opener to condition another stimulus: the squeaky cabinet (Figure L.5). It is hard to achieve anything above second-order conditioning. For example, if you ring a bell, open the cabinet (“squeak”), use the can opener (“zzhzhz”), and then feed Zelda, Zelda will likely never get excited when hearing the bell alone.

Everyday Connection

Classical Conditioning at Stingray City

Kate and her spouse recently vacationed in the Cayman Islands, and booked a boat tour to Stingray City, where they could feed and swim with the southern stingrays. The boat captain explained how the normally solitary stingrays have become accustomed to interacting with humans. About 40 years ago, fishermen began to clean fish and conch (unconditioned stimulus) at a particular sandbar near a barrier reef, and large numbers of stingrays would swim in to eat (unconditioned response) what the fishermen threw into the water; this continued for years. By the late 1980s, word of the large group of stingrays spread among scuba divers, who then started feeding them by hand. Over time, the southern stingrays in the area were classically conditioned much like Pavlov’s dogs. When they hear the sound of a boat engine (neutral stimulus that becomes a conditioned stimulus), they know that they will get to eat (conditioned response).

As soon as they reached Stingray City, over two dozen stingrays surrounded their tour boat. The couple slipped into the water with bags of squid, the stingrays’ favourite treat. The swarm of stingrays bumped and rubbed up against their legs like hungry cats (Figure L.6). Kate was able to feed, pet, and even kiss (for luck) these amazing creatures. Then all the squid was gone, and so were the stingrays.

Classical conditioning also applies to humans, even babies. For example, Logan buys formula in blue canisters for their six-month-old baby, Reagan. Whenever Logan takes out a formula container, Reagan gets excited, tries to reach toward the food, and most likely salivates. Why does Reagan get excited when they see the formula canister? What are the US, CS, UCR, and CR here?

So far, all of the examples have involved food, but classical conditioning extends beyond the basic need to be fed. Consider our earlier example of a dog whose owners install an invisible electric dog fence. A small electrical shock (unconditioned stimulus) elicits discomfort (unconditioned response). When the unconditioned stimulus (shock) is paired with a neutral stimulus (the edge of a yard), the dog associates the discomfort (unconditioned response) with the edge of the yard (conditioned stimulus) and stays within the set boundaries. In this example, the edge of the yard elicits fear and anxiety in the dog. Fear and anxiety are the conditioned response.

Link to Learning

Watch this clip from the show, The Office, for a funny look at an example of conditioning.

General Processes in Classical Conditioning

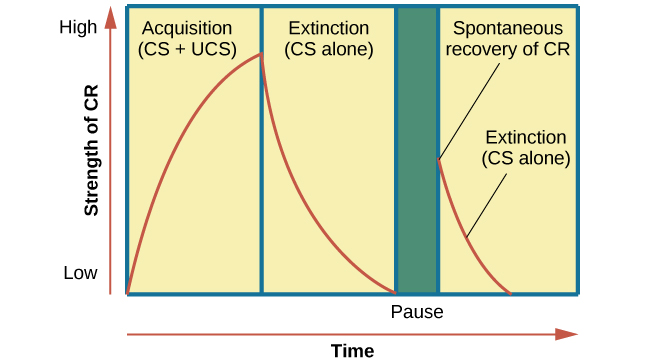

Now that you know how classical conditioning works and have seen several examples, let’s take a look at some of the general processes involved. In classical conditioning, the initial period of learning is known as acquisition, when an organism learns to connect a neutral stimulus and an unconditioned stimulus. During acquisition, the neutral stimulus begins to elicit the conditioned response, and eventually the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus capable of eliciting the conditioned response by itself. Timing is important for conditioning to occur. Typically, there should only be a brief interval between presentation of the conditioned stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus. Depending on what is being conditioned, sometimes this interval is as little as five seconds (Chance, 2009). However, with other types of conditioning, the interval can be up to several hours.

Taste aversion is a type of conditioning in which an interval of several hours may pass between the conditioned stimulus (something ingested) and the unconditioned stimulus (nausea or illness). Here’s how it works. Between classes, you and a friend grab a quick lunch from a food cart on campus. You share a dish of chicken curry and head off to your next class. A few hours later, you feel nauseous and become ill. Although your friend is fine and you determine that you have intestinal flu (the food is not the culprit), you’ve developed a taste aversion; the next time you are at a restaurant and someone orders curry, you immediately feel ill. While the chicken dish is not what made you sick, you are experiencing taste aversion: you’ve been conditioned to be averse to a food after a single, bad experience.

How does this occur—conditioning based on a single instance and involving an extended time lapse between the event and the negative stimulus? Research into taste aversion suggests that this response may be an evolutionary adaptation designed to help organisms quickly learn to avoid harmful foods (Garcia & Rusiniak, 1980; Garcia & Koelling, 1966). Not only may this contribute to species survival via natural selection, but it may also help us develop strategies for challenges such as helping cancer patients through the nausea induced by certain treatments (Holmes, 1993; Jacobsen et al., 1993; Hutton, Baracos, & Wismer, 2007; Skolin et al., 2006). Garcia and Koelling (1966) showed not only that taste aversions could be conditioned, but also that there were biological constraints to learning. In their study, separate groups of rats were conditioned to associate either a flavour with illness, or lights and sounds with illness. Results showed that all rats exposed to flavour-illness pairings learned to avoid the flavour, but none of the rats exposed to lights and sounds with illness learned to avoid lights or sounds. This added evidence to the idea that classical conditioning could contribute to species survival by helping organisms learn to avoid stimuli that posed real dangers to health and welfare.

TRICKY TOPIC: CONDITIONED TASTE AVERSION

For a full transcript of this video, click here

Robert Rescorla demonstrated how powerfully an organism can learn to predict the US from the CS. Take, for example, the following two situations. Tafadawa’s family always has dinner on the table every day at 6:00. Hai’s family switches it up so that some days they eat dinner at 6:00, some days they eat at 5:00, and other days they eat at 7:00. For Tafadawa, 6:00 reliably and consistently predicts dinner, so Tafadawa will likely start feeling hungry every day right before 6:00, even if he’s had a late snack. Hai, on the other hand, will be less likely to associate 6:00 with dinner, since 6:00 does not always predict that dinner is coming. Rescorla, along with his colleague at Yale University, Alan Wagner, developed a mathematical formula that could be used to calculate the probability that an association would be learned given the ability of a conditioned stimulus to predict the occurrence of an unconditioned stimulus and other factors; today this is known as the Rescorla-Wagner model (Rescorla & Wagner, 1972). We also know that conditioning can be unrelated to food. It can also trigger an emotional response, rather than a physical one. For example, if an experimenter sounds a tone just before applying a mild shock to a rat’s feet, the tone will elicit fear or anxiety after one or two pairings. Similar fear conditioning plays a role in creating many anxiety disorders in humans, such as phobias and panic disorders, where people associate cues (such as closed spaces, or a shopping mall) with panic or other emotional trauma. Here, rather than a physical response (like drooling), the CS triggers an emotion.

Once we have established the connection between the unconditioned stimulus and the conditioned stimulus, how do we break that connection and get the dog, cat, or child to stop responding? In Zelda’s case, imagine what would happen if you stopped using the electric can opener for their food and began to use it only for human food. Now, Zelda would hear the can opener, but she would not get food. In classical conditioning terms, you would be giving the conditioned stimulus, but not the unconditioned stimulus. Pavlov explored this scenario in his experiments with dogs: sounding the tone without giving the dogs the meat powder. Soon the dogs stopped responding to the tone. Extinction is the decrease in the conditioned response when the unconditioned stimulus is no longer presented with the conditioned stimulus. When presented with the conditioned stimulus alone, the dog, cat, or other organism would show a weaker and weaker response, and finally no response. In classical conditioning terms, there is a gradual weakening and disappearance of the conditioned response.

What happens when learning is not used for a while—when what was learned lies dormant? As we just discussed, Pavlov found that when he repeatedly presented the bell (conditioned stimulus) without the meat powder (unconditioned stimulus), extinction occurred; the dogs stopped salivating to the bell. However, after a couple of hours of resting from this extinction training, the dogs again began to salivate when Pavlov rang the bell. What do you think would happen with Zelda’s behaviour if your electric can opener broke, and you did not use it for several months? When you finally got it fixed and started using it to open Zelda’s food again, Zelda would remember the association between the can opener and food—they would get excited and run to the kitchen when they heard the sound. The behaviour of Pavlov’s dogs and Zelda illustrates a concept Pavlov called spontaneous recovery: the return of a previously extinguished conditioned response following a rest period (Figure L.7).

Of course, these processes also apply in humans. For example, let’s say that every day when you walk to campus, an ice cream truck passes your route. Day after day, you hear the truck’s music (neutral stimulus), so you finally stop and purchase a chocolate ice cream bar. You take a bite (unconditioned stimulus) and then your mouth waters (unconditioned response). This initial period of learning is known as acquisition, when you begin to connect the neutral stimulus (the sound of the truck) and the unconditioned stimulus (the taste of the chocolate ice cream in your mouth). During acquisition, the conditioned response gets stronger and stronger through repeated pairings of the conditioned stimulus and unconditioned stimulus. Several days (and ice cream bars) later, you notice that your mouth begins to water (conditioned response) as soon as you hear the truck’s musical jingle—even before you bite into the ice cream bar. Then one day you head down the street. You hear the truck’s music (conditioned stimulus), and your mouth waters (conditioned response). However, when you get to the truck, you discover that they are all out of ice cream. You leave disappointed. The next few days you pass by the truck and hear the music, but don’t stop to get an ice cream bar because you’re running late for class. You begin to salivate less and less when you hear the music, until by the end of the week, your mouth no longer waters when you hear the tune. This illustrates extinction. The conditioned response weakens when only the conditioned stimulus (the sound of the truck) is presented, without being followed by the unconditioned stimulus (chocolate ice cream in the mouth). Then the weekend comes. You don’t have to go to class, so you don’t pass the truck. Monday morning arrives and you take your usual route to campus. You round the corner and hear the truck again. What do you think happens? Your mouth begins to water again. Why? After a break from conditioning, the conditioned response reappears, which indicates spontaneous recovery.

Acquisition and extinction involve the strengthening and weakening, respectively, of a learned association. Two other learning processes—stimulus discrimination and stimulus generalization—are involved in determining which stimuli will trigger learned responses. Animals (including humans) need to distinguish between stimuli—for example, between sounds that predict a threatening event and sounds that do not—so that they can respond appropriately (such as running away if the sound is threatening). When an organism learns to respond differently to various stimuli that are similar, it is called stimulus discrimination. In classical conditioning terms, the organism demonstrates the conditioned response only to the conditioned stimulus. Pavlov’s dogs discriminated between the basic tone that sounded before they were fed and other tones (e.g., the doorbell), because the other sounds did not predict the arrival of food. Similarly, Zelda, the cat, discriminated between the sound of the can opener and the sound of the electric mixer. When the electric mixer is going, Zelda is not about to be fed, so they do not come running to the kitchen looking for food. In our other example, Farah, the cancer patient, discriminated between oncologists and other types of doctors. Farah learned not to feel ill when visiting doctors for other types of appointments, such as their annual physical.

On the other hand, when an organism demonstrates the conditioned response to stimuli that are similar to the condition stimulus, it is called stimulus generalization, the opposite of stimulus discrimination. The more similar a stimulus is to the condition stimulus, the more likely the organism is to give the conditioned response. For instance, if the electric mixer sounds very similar to the electric can opener, Zelda may come running after hearing its sound. But if you do not feed Zelda following the electric mixer sound, and you continue to feed them consistently after the electric can opener sound, Zelda will quickly learn to discriminate between the two sounds (provided they are sufficiently dissimilar that she can tell them apart). In our other example, Farah continued to feel ill whenever visiting other oncologists or other doctors in the same building as their oncologist.

Behaviorism

John B. Watson, shown in Figure L.8, is considered the founder of behaviourism. Behaviourism is a school of thought that arose during the first part of the 20th century, which incorporates elements of Pavlov’s classical conditioning (Hunt, 2007). In stark contrast with Freud, who considered the reasons for behaviour to be hidden in the unconscious, Watson championed the idea that all behaviour can be studied as a simple stimulus-response reaction, without regard for internal processes. Watson argued that in order for psychology to become a legitimate science, it must shift its concern away from internal mental processes because mental processes cannot be seen or measured. Instead, he asserted that psychology must focus on outward observable behaviour that can be measured.

Watson’s ideas were influenced by Pavlov’s work. According to Watson, human behaviour, just like animal behaviour, is primarily the result of conditioned responses. Whereas Pavlov’s work with dogs involved the conditioning of reflexes, Watson believed the same principles could be extended to the conditioning of human emotions (Watson, 1919). Thus began Watson’s work with his graduate student Rosalie Rayner and a baby called Little Albert. Through their experiments with Little Albert, Watson and Rayner (1920) demonstrated how fears can be conditioned.

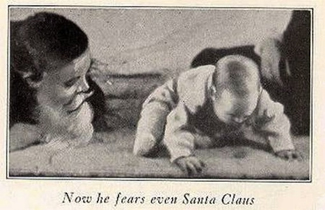

In 1920, Watson was the chair of the psychology department at Johns Hopkins University. Through his position at the university he came to meet Little Albert’s mother, Arvilla Merritte, who worked at a campus hospital (DeAngelis, 2010). Watson offered her a dollar to allow her son to be the subject of his experiments in classical conditioning. Through these experiments, Little Albert was exposed to and conditioned to fear certain things. Initially he was presented with various neutral stimuli, including a rabbit, a dog, a monkey, masks, cotton wool, and a white rat. He was not afraid of any of these things. Then Watson, with the help of Rayner, conditioned Little Albert to associate these stimuli with an emotion—fear. For example, Watson handed Little Albert the white rat, and Little Albert enjoyed playing with it. Then Watson made a loud sound, by striking a hammer against a metal bar hanging behind Little Albert’s head, each time Little Albert touched the rat. Little Albert was frightened by the sound—demonstrating a reflexive fear of sudden loud noises—and began to cry. Watson repeatedly paired the loud sound with the white rat. Soon Little Albert became frightened by the white rat alone. In this case, what are the US, CS, UCR, and CR? Days later, Little Albert demonstrated stimulus generalization—he became afraid of other furry things: a rabbit, a furry coat, and even a Santa Claus mask (Figure L.9). Watson had succeeded in conditioning a fear response in Little Albert, thus demonstrating that emotions could become conditioned responses. It had been Watson’s intention to produce a phobia—a persistent, excessive fear of a specific object or situation— through conditioning alone, thus countering Freud’s view that phobias are caused by deep, hidden conflicts in the mind. However, there is no evidence that Little Albert experienced phobias in later years. Little Albert’s mother moved away, ending the experiment. While Watson’s research provided new insight into conditioning, it would be considered unethical by today’s standards.

Link to Learning

View scenes from this video on John Watson’s experiment in which “Little Albert” was conditioned to respond in fear to furry objects, to learn more.