1.3 Personal Values and Social Identity

Linda Macdonald

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to

- Identify and prioritize personal core values

- Consider the cultural context from which these values developed

- Explain the importance of defining your social identity

- Define intersectionality

Relationships are key to business success. To collaborate effectively with team members, to establish trust with clients, to bring innovative ideas to new partners, and to meet expectations of management, it is essential to develop and maintain relationships. These relationships depend on shared personal and corporate values and on respectful engagement where there are differing values.

When you write a cover letter in application for a co-op position or summer job, you will aim to demonstrate your fit with the organization. Employers do not want employees who possess only technical and knowledge skills; they seek employees who can fit with and further the culture and values of the organization. This need for fit does not mean that you should pretend to be something you are not. You will not be happy in an organization with values that contradict your core personal values. Furthermore, your personal value set is unique to you. You will not be an exact fit with the values of any other person or any organization. Your differences contribute to diversity, which is essential for innovation and business growth.

We have probably all been told “Just be yourself”. What does that even mean? The word “just” makes it seem so simple. And “yourself”? What actions are displayed that hold this “self”? What is done or is not done that indicates that I am being “myself”?

You are “yourself” when your actions are aligned with your core values.

Core values are your foundational beliefs and attitudes. They guide an individual or organization’s decisions, behaviours, communications, and actions. Your core values define who you are and guide the choices you make and the things you do. As Susan Heathfield writes, core values “represent an individual’s or an organization’s highest priorities, deeply held beliefs, and core, fundamental driving forces. They are the heart of what your organization and its employees stand for in the world” (para. 1).

Co-op education programs often focus on work readiness and technical skills, but you will not be adequately prepared for your world without self-knowledge. To be an effective business communicator, you need to understand the values that govern your own behaviours as well as understand the values that guide those with whom you are communicating. In addition, understanding our social identities and how these identities have influenced our values, experiences, and opportunities can help us develop mutually respectful relationships.

Personal Values

In her book Presence, Amy Cuddy describes what she calls presence. Presence is “the state of being attuned to and able to comfortably express our true thoughts, feelings, values, and potential” (p. 24). Displaying presence results in appearing more authentic, believable, and genuine.

You can only be truly present, truly yourself, if your words and actions are aligned with your current values. Being clear with what these values are can help you achieve presence. The values you prioritize today may not be the ones you prioritize as you progress in age and in your career and family life. For example, you may prioritize adventure and friendship now but, because of life events, you may prioritize community and family in five years. Working in alignment with your values, even as they change, is important for personal and professional success.

Exercise: Personal Identity Worksheet

Work through the Core Values Exercise adapted from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Share your list of core values with your peers to identify shared values and interesting differences. Spend a few minutes discussing how you developed these personal values. What experiences or environments contributed to the strength of these values for you?

Social Identity

Navigating the gap between your values and the values of others requires awareness and sensitivity. Firstly, we need to be aware that our personal identities are influenced by our social identities.

As humans, we are driven to seek connections and establish our place in society. If you are a first-year business student, your social identity may be defined by your year in school, degree program, residence, and university. Your membership in these groups may lead you to align yourself with other first-year students in the residence hall, to take pride in and ownership of the Management Building, and to wear school colours at sports events and then celebrate at a particular pub. Your social affiliations define both who you are and who you are not. You may think of your status as a Commerce student as better than that of an Arts and Sciences student or better than that of a student who attends the university down the road. The distinction between you and the student at a neighbouring university is arbitrary yet can prompt strong emotions of pride and competitiveness.

In addition to identifying with your year, program, and university, you may belong to other groups (either by choice or by birth) based on your hometown, preferred hockey team, native language, religious preferences, racial identity, gender, or sexual orientation.

Henri Tajifel and John Turner defined social identity theory in the 1970s. Social identity results from a process of social categorization, social identification, and social comparison.

- Social categorization is “the process by which we organize individuals into social groups in order to understand our social world”. According to Vinney, “we tend to define people based on their social categories more often than their individual characteristics” (Vinney, 2019, para. 7).

- Social identification is the process of identifying as a member of the in-group and taking on the group’s characteristics. Our identification with the group leads to emotional investment in the group’s success, which then contributes to our self-esteem.

- Social comparison is the process of comparing the in-group to other groups, or out-groups.

Watch this 13-minute video, which contains 5 questions for you to answer. At the end of the video, click the button to submit your answers.

(Direct link to Us vs. Them: The Science of Social Identity Theory video)

Whether we selected a group or were born into it, our membership in the group comes with certain benefits. For example, as a student you have access to resources and library materials that people who do not belong to the university cannot as readily access. If you are a native speaker of English, you speak naturally and do not have to think about how to respond to a question in a grammatically acceptable way. If you are white, you likely find it easy to buy make-up that matches your skin tone or magazines that include images of people who look like you.

Our social identities also come with disadvantages. You may have the advantage of a strong network within the 2+LGBTQ community, but still face social stigma in places that lack gender-neutral restrooms. You may feel pride in your country of origin but frightened by anti-Asian racism. You may feel a strong sense of belonging within the Muslim community but feel judged and avoided in a classroom in which you are the only one wearing a hijab. You may feel proud to be an Indian international student but stigmatized by an historic socioeconomic system and post-colonial practices that still affect Indian access to opportunities in the workplace.

Experiences outside of your social categories will help you understand the advantages and disadvantages others experience. In moving outside the groups with which you have strong social identities, you may discover new approaches to complex problems and creative solutions. In addition, bridging categories can create better relationships between team members, a greater sense of belonging for all members, and collaborations that lead to innovative ideas. You will bring to future employers skills that lead to intellectual and economic success.

Exercise: Social Identity Chart

1. Creating a social identity wheel can help you think through your various social identities and the advantages and disadvantages that come with them. Sharing your findings can help you find common ground as well as identify differences. These differences can lead to new ways of seeing, understanding, and respecting the perspectives of others. In completing your Social Identity Chart, you might consider your

- cultural background,

- first language,

- marital status,

- age,

- learning ability,

- social class or and socioeconomic status,

- religion,

- ethnicity,

- sexual orientation,

- gender,

- citizenship,

- physical abilities, or

- any social category that contributes to your identity.

2. Discuss:

(a) Which identities most influence your view of yourself? Which identities do you think most affect the way others see you?

(b) What are the advantages and disadvantages of membership in each group?

(c) In what ways does your social identity with one group conflict with your social identity with another group? For example, a dual citizen might identify with the country they are living in and join with the majority of that group in condemning the actions of their home country, a country with which the person also closely identifies. How might similar conflicts affect your communications?

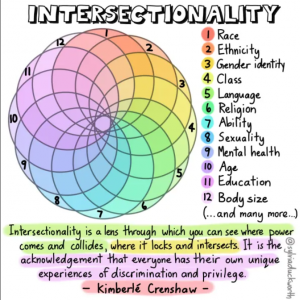

Intersectionality

Kimberlé Crenshaw tells the story of Emma DeGraffenreid, who sued General Motors in 1976 for racial and gender discrimination. Because both Blacks and women were employed by the company and had opportunity to advance, the court found that General Motors was not discriminating against women, nor were they discriminating against Blacks. DeGraffenreid lost her case. In her 2016 TED Talk, Crenshaw discussed the failure of the court to see the discrimination that Black women faced as a result of being both Black and female. The court only understood the harm she experienced on the race road or the gender road and could not understand the harm experienced at the intersection of these roads.

Crenshaw (1989) coined the term “intersectionality” to refer to the ways in which DeGraffenreid and the other women who sued GM experienced a combination of racial and gender discrimination. Today, the term “intersectionality” refers to a broad range of overlapping social identities that experience discrimination.

Understanding intersectionality can help you in identifying the needs, expectations, and perspectives of your audience. As the Government of Canada’s (n.d.) “Introduction to Intersectionality” states,

Understanding intersectionality can help you in identifying the needs, expectations, and perspectives of your audience. As the Government of Canada’s (n.d.) “Introduction to Intersectionality” states,

It is essential to recognize that people have multiple and diverse identity factors that intersect to shape their perspectives, ideologies and experiences. For example, consider the multiple identity factors of an immigrant man with a disability. Rather than isolating the experience of being an immigrant from that of being a man from that of being a person with a disability, adopting an intersectional approach will enable you to see this individual as a whole being, with multiple identity factors.

This 4-minute video explains the complexity of intersectionality. Awareness of these complexities can help in understanding the experiences of our colleagues, customers, and other stakeholders in a business environment.

(Direct link to What is Intersectionality and Why is it Important? video)

One Foot in Two Canoes

While multiple social identities foster an ability to see a problem from different perspectives, social identities may also be difficult to harmonize. The following section is from Indigenous Lifeways in Canadian Business by Russell Evans, Michael Mihalicz, and Maureen Sterling:

Culture is fundamentally a social phenomenon that we acquire through frequent and consistent interaction with our close social groups. One’s cultural identity typically stems from the amalgamation of where one is born and among whom they’re raised. Indigenous business leaders must often balance the demands of their profession with their cultural and community roots, leaving their communities to further their professional careers. To have “one foot in two canoes” is described by author Beverly McBride as simultaneously participating in both traditional cultural lifeways and Western business practices. Because of the separation from traditional lands and the demands of their career, Indigenous professionals strive to maintain a connection with their community. Krystal Abotossaway, Indigenous entrepreneur and president of IPAC, describes how she maintains balance while working away from home by nurturing her connection to the reserve community. Indigenous artist and entrepreneur Alex Jacobs-Blum shares her experiences with choosing her community’s needs as a motivation for the work she performs.

“One Foot in Two Canoes“, by University of Windsor, is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Conclusion

Your personal values and your social identities create the unique person that you are. Clarity on these identities will help in presenting your personal brand effectively to employers, establishing common ground with team members, understanding and connecting with customers and clients from diverse backgrounds, and reconciling your multiple social identities.

Social Identity and Power

In this drawing, Sylvia Duckworth illustrates the relationship between identity and power. The closer you are to the centre of the circle, the more power you likely hold in the existing power structures in North American culture. The further you move to the outside rim of the circle, the less power you likely hold and the more marginalized you are. You may find that you hold power in some categories but be marginalized by other identities. Your colleagues, clients, and partners in the workplace will have needs and experiences of power that differ with their unique set of identities. A transgender person of colour will have needs that differ from those of an older, white, neuro-atypical, cisgender man or a married Middle Eastern cisgender woman. Awareness of your own positions in the circle and a respect for the positions of others will help you establish effective business communication.

1. Identify your multiple identities in the circle. Share your your experiences of power and marginalization with your group.

2. Are there additional social identities that should be included in this chart? Do you see any shifts in culture that may change the power structure?

References

Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersections of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), Article 8. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8/

Cuddy, A. (2015). Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges. Little, Brown and Company.

Evans, R.A., Sterling, M., Mihalicz, M. (2022). Indigenous Lifeways in Canadian Business: Instructor Guide. University of Windsor. http://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/indigenousbusinesstopics/

Government of Canada (n.d.). Introduction to Intersectionality. https://women-gender-equality.canada.ca/gbaplus-course-cours-acsplus/eng/mod02/mod02_03_01a.html

Heathfield, S.M. (February 26, 2021) Core values are what you believe. The Balance Careers. https://www.thebalancecareers.com/core-values-are-what-you-believe-1918079

McCracken, G. (January 4, 2013). Facilitating serendipity with peel-and-eat shrimp.https://hbr.org/2013/01/facilitating-serendipity-with-peel-and-eat-shrimp

Vinney, C. (July 22, 2019). Understanding social identity theory and its impact on behavior. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/social-identity-theory-4174315

Photos: “Kimberlé Crenshaw” by boellstiftung licensed under CC-BY-SA

“Intersectionality” and “Wheel of Power/Privilege” by Sylvia Duckworth used with permission from the artist