1.2 The Responsibilities of Business Communicators

[Author removed at request of original publisher] and Linda Macdonald

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to

- Explain the responsibilities you have to your audience, employer, and profession to be prepared

- Outline the responsibilities of an ethical business communicator

Self-Assessment

What did your self-assessment reveal about your habits? Students typically don’t think of themselves as business professionals, yet as co-op students you will soon enter a workplace that expects you to adhere to industry performance standards. If you checked true on seven statements or above, you are on your way to meeting your future employers’ expectations of your communication behaviours. If you checked true on six or fewer, you may need to change your behaviours to meet the expectations of your employers, colleagues, and clients.

Whenever you speak or write in a business environment, you have certain responsibilities to your audience, your employer, and your profession. Your audience comes to you with expectations that you will fulfill these responsibilities. The specific expectations may change given the context or environment, but two central qualities remain: Be prepared, and be ethical.

Be Prepared

As the business communicator’s first responsibility, preparation includes being organized, communicating clearly, and being concise and punctual.

The Prepared Communicator Is Organized

Part of being prepared is being organized. Aristotle called this logos, or logic, which includes the steps or points that lead your communication to a conclusion. Once you’ve invested time in researching your topic, you will want to narrow your focus to a few key points and consider how you’ll present them.

You also need to consider how to link your main points together for your audience. Use transitions to provide signposts or cues for your audience to follow along. “Now that we’ve examined X, let’s consider Y” is a transitional statement that provides a cue that you are moving from topic to topic. Your listeners or readers will appreciate that you are well organized so that they can follow your message from point to point.

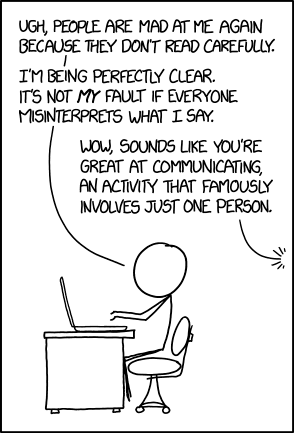

The Prepared Communicator Is Clear

You have probably had the unhappy experience of reading or listening to a communication that was vague and wandering. Part of being prepared is being clear. If your message is unclear, the audience will lose interest and tune you out, bringing an end to effective communication.

You need to have a clear idea in your mind of what you want to say before you can say it clearly to someone else. Decide what the single most important point is that you wish to make and how you want the audience to think or feel when they see or hear it. Clarity considers the audience; you will want to choose words and phrases they understand and avoid jargon or slang that may be unfamiliar to them.

Your use of visual rhetoric can affect clarity. Illegible handwriting or a slide with insufficient colour contrast will not be clear. If you mumble your words, speak too quickly, use a monotonous tone of voice, or stumble over certain words or phrases, the clarity of your presentation will suffer.

Technology can also affect clarity. If you are using a microphone or conducting a teleconference, clarity will depend on this equipment functioning properly—which brings us back to the importance of preparation. In this case, in addition to preparing your speech, you need to prepare by testing the equipment ahead of time.

The Prepared Communicator Is Concise and Punctual

Good business communication does not waste words or time. Concise means brief and to the point. In most business communications you are expected to get to the point right away. Being prepared includes being able to state your points clearly and supporting them with evidence in a straightforward, linear way.

It may be tempting to show how much you know by incorporating additional information into your document or speech, but in so doing you run the risk of boring, confusing, or overloading your audience. Talking in circles or indulging in tangents by getting off topic or going too deep can hinder an audience’s ability to grasp your message. Be to the point and concise in your choice of words, organization, and visual aids.

Being concise also involves being sensitive to time constraints. In preparing a presentation for a meeting, time yourself when you rehearse to make sure you can deliver your message within the allotted number of minutes.

There are exceptions to this principle of conciseness and punctuality. Many non-Western cultures prefer a less direct approach and begin interactions with social or general comments that a Canadian or American audience might consider unnecessary. Some cultures also have a less strict interpretation of time schedules and punctuality. Different cultures have different expectations, and you may need to adapt the level of directness to audience needs.

Photo: “business people” by HerrWick is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Be Ethical

The business communicator’s second fundamental responsibility is to be ethical. Ethics refers to a set of principles or rules for correct conduct. It echoes what Aristotle called ethos, the communicator’s good character and reputation for doing what is right. Communicating ethically involves being egalitarian, respectful, and trustworthy.

Communication can move communities, influence cultures, and change history. It can motivate people to take a stand, consider an argument, or purchase a product. The degree to which you consider both the common good and fundamental principles you hold to be true when crafting your message directly relates to how your message will affect others.

The Ethical Communicator Is Egalitarian

The word “egalitarian” comes from the root “equal.” To be egalitarian is to believe in basic equality: that all people should share equally in the benefits and burdens of a society. It means that everyone is entitled to the same respect, expectations, access to information, and rewards of participation in a group.

To communicate in an egalitarian manner, speak and write in a way that is comprehensible and relevant to all your listeners or readers.

In business, you will often communicate with people who have certain professional qualifications. For example, you may draft a memo addressed to all the nurses in a certain hospital, or give a speech to all the adjusters in a certain branch of an insurance company. Being egalitarian does not mean you have to avoid professional terminology that is understood by nurses or insurance adjusters. But it does mean that your hospital letter should be worded for all the hospital’s nurses—not just female nurses, not just nurses working directly with patients, not just nurses under age fifty-five. An egalitarian communicator seeks to unify the audience by using ideas and language that are appropriate for all the message’s readers or listeners.

The Ethical Communicator Is Respectful

People are influenced by emotions as well as logic. Aristotle named pathos, or passion, enthusiasm and energy, as the third of his three important parts of communicating in addition to logos and ethos.

Most of us have probably seen an audience manipulated by a “cult of personality,” believing whatever the speaker said simply because of how dramatically they delivered a speech; by being manipulative, the speaker fails to respect the audience. We may have also seen people hurt by sarcasm, insults, and other disrespectful forms of communication.

Passion and enthusiasm are not out of place in business communication, however. Indeed, they are very important. You cannot expect your audience to care about your message if you don’t show that you care about it yourself. If your topic is worth writing or speaking about, make an effort to show your audience why it is worthwhile by speaking enthusiastically or using a dynamic writing style. Doing so, in fact, shows respect for their time and their intelligence.

However, the ethical communicator will be passionate and enthusiastic without being disrespectful. Losing one’s temper and being abusive are generally regarded as a lack of professionalism (and could even involve legal consequences for you or your employer). When you disagree strongly with a coworker, feel deeply annoyed with a difficult customer, or find serious fault with a competitor’s product, it is important to express such sentiments respectfully. For example, instead of telling a customer “I’ve had it with your complaints!”, a respectful business communicator might say, “I’m having trouble seeing how I can fix this situation. Would you explain to me what you want to see happen?”

The Ethical Communicator Is Trustworthy

Trust is a key component in communication and especially in business communication. As a consumer, would you choose to buy merchandise from a company you did not trust? If you were an employer, would you hire someone you did not trust?

Your goal as a communicator is to build a healthy relationship with your audience, and to do that you should show them why they can trust you and why the information you are about to give them is believable. One way to do this is to begin your message by providing some information about your qualifications and background, your interest in the topic, or your reasons for communicating at this particular time.

Your audience will expect that what you say is the truth as you understand it and that you have not intentionally omitted, deleted, or taken information out of context simply to prove your points. They will listen to what you say and how you say it, but also to what you don’t say or do. Acknowledging different perspectives or opposing views indicates that you have carefully considered the available options.

Being worthy of trust is something you earn with an audience. Trust is hard to build but easy to lose. A communicator may be asked a question, not know the answer, and still be trustworthy, but it’s a violation of trust to pretend you know something when you don’t.

Words and Your Legal Responsibility

Your writing in a business context means that you represent yourself and your company. What you write and how you write it can be part of your company’s success but can also expose it to unintended consequences and legal responsibility. When you write, keep in mind that your words will keep on existing long after you have moved on to other projects. They can become an issue if they exaggerate, state false claims, or defame a person or legal entity such as a competing company. Another issue is plagiarism, using someone else’s writing without giving credit to the source. Whether the material is taken from a printed book, a Web site, or a blog, plagiarism is a violation of copyright law.

Beware of using ChatGPT and other artificial intelligence (AI)-generated content. Information produced by AI may be factually incorrect or outdated. AI often reproduces content from human-generated sources without appropriate attribution. Reusing this content can have unfortunate consequences. Whether you are writing as a student or as an employee, use of AI-generated material can result in the spread of misinformation and disinformation or charges of plagiarism that can damage your reputation and that of your employer. Even AI tools that claim to put citations in APA style make errors that compromise your credibility. AI promises to make work faster and easier in the future, but in the meantime, humans with communication skills are more reliable and best able to build relationships with business communication.

Libel is the written form of defamation, or a false statement that damages a reputation. If a false statement of fact that concerns and harms the person defamed is published—including publication in a digital or online environment—the author of that statement may be sued for libel. If the person defamed is a public figure, they must prove malice or the intention to do harm, but if the victim is a private person, libel applies even if the offence cannot be proven to be malicious.

The Platinum Rule

The “golden rule” says to treat others the way you would like to be treated. The golden rule asks you to consider how you would feel if you were on the receiving end of your communication, and act accordingly.

In The Art of People, Dave Kerpen (2016) proposes the “platinum rule”:

We all grow up learning about the simplicity and power of the Golden Rule: Do unto others as you would want done to you. It’s a splendid concept except for one thing: Everyone is different, and the truth is that in many cases what you’d want done to you is different from what your partner, employee, customer, investor, wife, or child would want done to [them]. (p. 96)

Kerpen recommends the platinum rule: “Do unto others as they would want done to them” (p. 96): “If you’re doing a great job listening, mirroring, and validating, and if you’re being your authentic, vulnerable, present self, you should be able to see the other person’s perspective and apply the Platinum Rule without a problem” (p. 98).

Applying the platinum rule to your communications promotes human kindness, cooperation, and reciprocity across cultures, languages, backgrounds and interests.

Answer all the following questions. Be sure to work all the way through to the last slide.

Check Your Knowledge (13 Questions)

Discussion Questions

- Have you worked with a manager or team leader who was “prepared” in the ways described in this chapter? What did this manager do that demonstrated this preparation? Have you worked with someone who lacked this preparation? How was this lack of preparation exhibited?

- What are the characteristics of the ethical communicator? Provide an example from your experience of a communicator who failed to apply these principles in communicating with you verbally or in writing.

- What are specific techniques you can use to demonstrate egalitarianism, respectfulness, and trustworthiness in a presentation? In written documents?

References

Kerpen, D. (2016). The art of people. Crown Business.