Key Concepts

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Explain how the binding of a ligand initiates signal transduction throughout a cell

- Recognize the role of phosphorylation in the transmission of intracellular signals

- Evaluate the role of second messengers in signal transmission

Once a ligand binds to a receptor, the signal is transmitted through the membrane and into the cytoplasm. Continuation of a signal in this manner is called signal transduction. Signal transduction only occurs with cell-surface receptors, which cannot interact with most components of the cell such as DNA. Only internal receptors are able to interact directly with DNA in the nucleus to initiate protein synthesis.

When a ligand binds to its receptor, conformational changes occur that affect the receptor’s intracellular domain. Conformational changes of the extracellular domain upon ligand binding can propagate through the membrane region of the receptor and lead to activation of the intracellular domain or its associated proteins. In some cases, binding of the ligand causes dimerization of the receptor, which means that two receptors bind to each other to form a stable complex called a dimer. A dimer is a chemical compound formed when two molecules (often identical) join together. The binding of the receptors in this manner enables their intracellular domains to come into close contact and activate each other.

Binding Initiates a Signaling Pathway

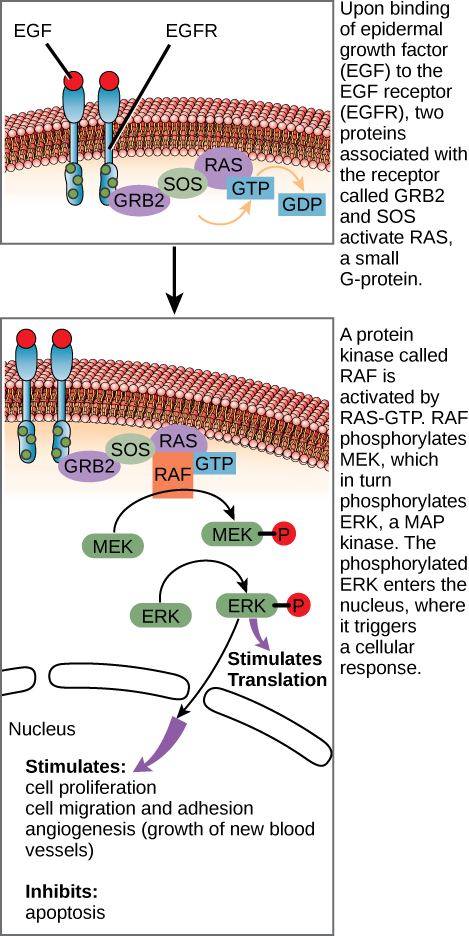

After the ligand binds to the cell-surface receptor, the activation of the receptor’s intracellular components sets off a chain of events that is called a signaling pathway, sometimes called a signaling cascade. In a signaling pathway, second messengers–enzymes–and activated proteins interact with specific proteins, which are in turn activated in a chain reaction that eventually leads to a change in the cell’s environment (Figure 9.10), such as an increase in metabolism or specific gene expression. The events in the cascade occur in a series, much like a current flows in a river. Interactions that occur before a certain point are defined as upstream events, and events after that point are called downstream events.

Visual Connection

In certain cancers, the GTPase activity of the RAS G-protein is inhibited. This means that the RAS protein can no longer hydrolyze GTP into GDP. What effect would this have on downstream cellular events?

You can see that signaling pathways can get very complicated very quickly because most cellular proteins can affect different downstream events, depending on the conditions within the cell. A single pathway can branch off toward different endpoints based on the interplay between two or more signaling pathways, and the same ligands are often used to initiate different signals in different cell types. This variation in response is due to differences in protein expression in different cell types. Another complicating element is signal integration of the pathways, in which signals from two or more different cell-surface receptors merge to activate the same response in the cell. This process can ensure that multiple external requirements are met before a cell commits to a specific response.

The effects of extracellular signals can also be amplified by enzymatic cascades. At the initiation of the signal, a single ligand binds to a single receptor. However, activation of a receptor-linked enzyme can activate many copies of a component of the signaling cascade, which amplifies the signal.

Link to Learning

Methods of Intracellular Signaling

The induction of a signaling pathway depends on the modification of a cellular component by an enzyme. There are numerous enzymatic modifications that can occur, and they are recognized in turn by the next component downstream. The following are some of the more common events in intracellular signaling.

Phosphorylation

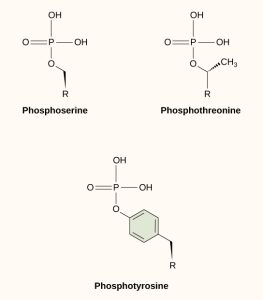

One of the most common chemical modifications that occurs in signaling pathways is the addition of a phosphate group (PO4–3) to a molecule such as a protein in a process called phosphorylation. The phosphate can be added to a nucleotide such as GMP to form GDP or GTP. Phosphates are also often added to serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues of proteins, where they replace the hydroxyl group of the amino acid (Figure 9.11). The transfer of the phosphate is catalyzed by an enzyme called a kinase. Various kinases are named for the substrate they phosphorylate. Phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues often activates enzymes. Phosphorylation of tyrosine residues can either affect the activity of an enzyme or create a binding site that interacts with downstream components in the signaling cascade. Phosphorylation may activate or inactivate enzymes, and the reversal of phosphorylation, dephosphorylation by a phosphatase, will reverse the effect.

Second Messengers

Second messengers are small molecules that propagate a signal after it has been initiated by the binding of the signaling molecule to the receptor. These molecules help to spread a signal through the cytoplasm by altering the behavior of certain cellular proteins.

Calcium ion is a widely used second messenger. The free concentration of calcium ions (Ca2+) within a cell is very low because ion pumps in the plasma membrane continuously remove it by using adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP). For signaling purposes, Ca2+ is stored in cytoplasmic vesicles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum, or accessed from outside the cell. When signaling occurs, ligand-gated calcium ion channels allow the higher levels of Ca2+ that are present outside the cell (or in intracellular storage compartments) to flow into the cytoplasm, which raises the concentration of cytoplasmic Ca2+. The response to the increase in Ca2+ varies and depends on the cell type involved. For example, in the β-cells of the pancreas, Ca2+ signaling leads to the release of insulin, and in muscle cells, an increase in Ca2+ leads to muscle contractions.

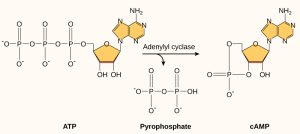

Another second messenger utilized in many different cell types is cyclic AMP (cAMP). Cyclic AMP is synthesized by the enzyme adenylyl cyclase from ATP (Figure 9.12). The main role of cAMP in cells is to bind to and activate an enzyme called cAMP-dependent kinase (A-kinase). A-kinase regulates many vital metabolic pathways: It phosphorylates serine and threonine residues of its target proteins, activating them in the process. A-kinase is found in many different types of cells, and the target proteins in each kind of cell are different. Differences give rise to the variation of the responses to cAMP in different cells.

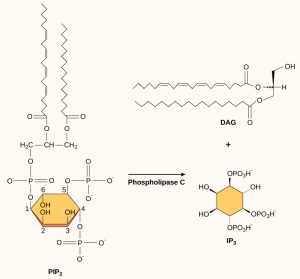

Present in small concentrations in the plasma membrane, inositol phospholipids are lipids that can also be converted into second messengers. Because these molecules are membrane components, they are located near membrane-bound receptors and can easily interact with them. Phosphatidylinositol (PI) is the main phospholipid that plays a role in cellular signaling. Enzymes known as kinases phosphorylate PI to form PI-phosphate (PIP) and PI-bisphosphate (PIP2).

The enzyme phospholipase C cleaves PIP2 to form diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol triphosphate (IP3) (Figure 9.13). These products of the cleavage of PIP2 serve as second messengers. Diacylglycerol (DAG) remains in the plasma membrane and activates protein kinase C (PKC), which then phosphorylates serine and threonine residues in its target proteins. IP3 diffuses into the cytoplasm and binds to ligand-gated calcium channels in the endoplasmic reticulum to release Ca2+ that continues the signal cascade.

Link to Learning

Cell signaling video from Professor Dave explains Receptors: Signal Transduction and Phosphorylation Cascade