Key Concepts

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Discuss the concept of entropy

- Explain the first and second laws of thermodynamics

Thermodynamics refers to the study of energy and energy transfer involving physical matter. The matter and its environment relevant to a particular case of energy transfer are classified as a system, and everything outside that system is the surroundings. For instance, when heating a pot of water on the stove, the system includes the stove, the pot, and the water. Energy transfers within the system (between the stove, pot, and water). There are two types of systems: open and closed. An open system is one in which energy and matter can transfer between the system and its surroundings. The stovetop system is open because it can lose heat into the air. A closed system is one that can transfer energy but not matter to its surroundings.

Biological organisms are open systems. Energy exchanges between them and their surroundings, as they consume energy-storing molecules and release energy to the environment by doing work. Like all things in the physical world, energy is subject to the laws of physics. The laws of thermodynamics govern the transfer of energy in and among all systems in the universe.

The First Law of Thermodynamics

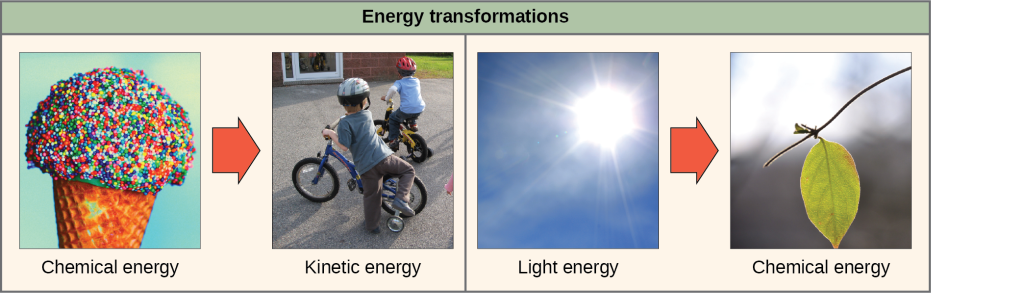

The first law of thermodynamics deals with the total amount of energy in the universe. It states that this total amount of energy is constant. In other words, there has always been, and always will be, exactly the same amount of energy in the universe. Energy exists in many different forms. According to the first law of thermodynamics, energy may transfer from place to place or transform into different forms, but it cannot be created or destroyed. The transfers and transformations of energy take place around us all the time. Light bulbs transform electrical energy into light energy. Gas stoves transform chemical energy from natural gas into heat energy. Plants perform one of the most biologically useful energy transformations on earth: that of converting sunlight energy into the chemical energy stored within organic molecules (Figure 6.2). Figure 6.11 examples of energy transformations.

The challenge for all living organisms is to obtain energy from their surroundings in forms that they can transfer or transform into usable energy to do work. Living cells have evolved to meet this challenge very well. Chemical energy stored within organic molecules such as sugars and fats transforms through a series of cellular chemical reactions into energy within ATP molecules. Energy in ATP molecules is easily accessible to do work. Examples of the types of work that cells need to do include building complex molecules, transporting materials, powering the beating motion of cilia or flagella, contracting muscle fibers to create movement, and reproduction.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics

A living cell’s primary tasks of obtaining, transforming, and using energy to do work may seem simple. However, the second law of thermodynamics explains why these tasks are harder than they appear. None of the energy transfers that we have discussed, along with all energy transfers and transformations in the universe, is completely efficient. In every energy transfer, some amount of energy is lost in a form that is unusable. In most cases, this form is heat energy. Thermodynamically, scientists define heat energy as energy that transfers from one system to another that is not doing work. For example, when an airplane flies through the air, it loses some of its energy as heat energy due to friction with the surrounding air. This friction actually heats the air by temporarily increasing air molecule speed. Likewise, some energy is lost as heat energy during cellular metabolic reactions. This is good for warm-blooded creatures like us, because heat energy helps to maintain our body temperature. Strictly speaking, no energy transfer is completely efficient, because some energy is lost in an unusable form.

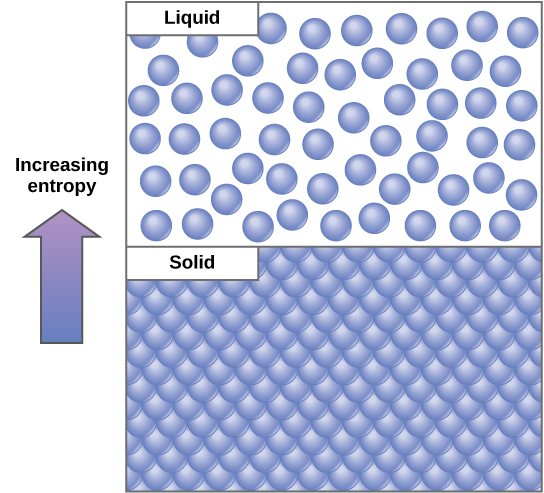

An important concept in physical systems is that of order and disorder (or randomness). The more energy that a system loses to its surroundings, the less ordered and more random the system. Scientists refer to the measure of randomness or disorder within a system as entropy. High entropy means high disorder and low energy (Figure 6.12). To better understand entropy, think of a student’s bedroom. If no energy or work were put into it, the room would quickly become messy. It would exist in a very disordered state, one of high entropy. Energy must be put into the system, in the form of the student doing work and putting everything away, in order to bring the room back to a state of cleanliness and order. This state is one of low entropy. Similarly, a car or house must be constantly maintained with work in order to keep it in an ordered state. Left alone, a house’s or car’s entropy gradually increases through rust and degradation. Molecules and chemical reactions have varying amounts of entropy as well. For example, as chemical reactions reach a state of equilibrium, entropy increases, and as molecules at a high concentration in one place diffuse and spread out, entropy also increases.

Scientific Method Connection

Transfer of Energy and the Resulting Entropy

Set up a simple experiment to understand how energy transfers and how a change in entropy results.

- Take a block of ice. This is water in solid form, so it has a high structural order. This means that the molecules cannot move very much and are in a fixed position. The ice’s temperature is 0°C. As a result, the system’s entropy is low.

- Allow the ice to melt at room temperature. What is the state of molecules in the liquid water now? How did the energy transfer take place? Is the system’s entropy higher or lower? Why?

- Heat the water to its boiling point. What happens to the system’s entropy when the water is heated?

Think of all physical systems of in this way: Living things are highly ordered, requiring constant energy input to maintain themselves in a state of low entropy. As living systems take in energy-storing molecules and transform them through chemical reactions, they lose some amount of usable energy in the process, because no reaction is completely efficient. They also produce waste and by-products that are not useful energy sources. This process increases the entropy of the system’s surroundings. Since all energy transfers result in losing some usable energy, the second law of thermodynamics states that every energy transfer or transformation increases the universe’s entropy. Even though living things are highly ordered and maintain a state of low entropy, the universe’s entropy in total is constantly increasing due to losing usable energy with each energy transfer that occurs. Essentially, living things are in a continuous uphill battle against this constant increase in universal entropy.