Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Define “energy”

- Explain the difference between kinetic and potential energy

- Discuss the concepts of free energy and activation energy

- Describe endergonic and exergonic reactions

We define energy as the ability to do work. As you’ve learned, energy exists in different forms. For example, electrical energy, light energy, and heat energy are all different energy types. While these are all familiar energy types that one can see or feel, there is another energy type that is much less tangible. Scientists associate this energy with something as simple as an object above the ground. In order to appreciate the way energy flows into and out of biological systems, it is important to understand more about the different energy types that exist in the physical world.

Energy Types

When an object is in motion, there is energy. For example, an airplane in flight produces considerable energy. This is because moving objects are capable of enacting a change, or doing work. Think of a wrecking ball. Even a slow-moving wrecking ball can do considerable damage to other objects. However, a wrecking ball that is not in motion is incapable of performing work. Energy with objects in motion is kinetic energy. A speeding bullet, a walking person, rapid molecule movement in the air (which produces heat), and electromagnetic radiation like light all have kinetic energy.

What if we lift that same motionless wrecking ball two stories above a car with a crane? If the suspended wrecking ball is unmoving, can we associate energy with it? The answer is yes. The suspended wrecking ball has associated energy that is fundamentally different from the kinetic energy of objects in motion. This energy form results from the potential for the wrecking ball to do work. If we release the ball it would do work. Because this energy type refers to the potential to do work, we call it potential energy. Objects transfer their energy between kinetic and potential in the following way: As the wrecking ball hangs motionless, it has 0 kinetic and 100 percent potential energy. Once it releases, its kinetic energy begins to increase because it builds speed due to gravity. Simultaneously, as it nears the ground, it loses potential energy. Somewhere mid-fall it has 50 percent kinetic and 50 percent potential energy. Just before it hits the ground, the ball has nearly lost its potential energy and has near-maximal kinetic energy. Other examples of potential energy include water’s energy held behind a dam (Figure 6.6), or a person about to skydive from an airplane.

We associate potential energy not only with the matter’s location (such as a child sitting on a tree branch), but also with the matter’s structure. A spring on the ground has potential energy if it is compressed; so does a tautly pulled rubber band. The very existence of living cells relies heavily on structural potential energy. On a chemical level, the bonds that hold the molecules’ atoms together have potential energy. Remember that anabolic cellular pathways require energy to synthesize complex molecules from simpler ones, and catabolic pathways release energy when complex molecules break down. That certain chemical bonds’ breakdown can release energy implies that those bonds have potential energy. In fact, there is potential energy stored within the bonds of all the food molecules we eat, which we eventually harness for use. This is because these bonds can release energy when broken. Scientists call the potential energy type that exists within chemical bonds that releases when those bonds break chemical energy (Figure 6.7). Chemical energy is responsible for providing living cells with energy from food. Breaking the molecular bonds within fuel molecules brings about the energy’s release.

Link to Learning

Free Energy

After learning that chemical reactions release energy when energy-storing bonds break, an important next question is how do we quantify and express the chemical reactions with the associated energy? How can we compare the energy that releases from one reaction to that of another reaction? We use a measurement of free energy to quantitate these energy transfers. Scientists call this free energy Gibbs free energy (abbreviated with the letter G) after Josiah Willard Gibbs, the scientist who developed the measurement. According to the second law of thermodynamics, all energy transfers involve losing some energy in an unusable form such as heat, resulting in entropy. Gibbs free energy specifically refers to the energy that takes place with a chemical reaction that is available after we account for entropy. In other words, Gibbs free energy is usable energy, or energy that is available to do work.

Every chemical reaction involves a change in free energy, called delta G (∆G). We can calculate the change in free energy for any system that undergoes such a change, such as a chemical reaction. To calculate ∆G, subtract the amount of energy lost to entropy (denoted as ∆S) from the system’s total energy change. The total energy in the system is enthalpy and we denote it as ∆H. The formula for calculating ∆G is as follows, where the symbol T refers to absolute temperature in Kelvin (degrees Celsius + 273):

We express a chemical reaction’s standard free energy change as an amount of energy per mole of the reaction product (either in kilojoules or kilocalories, kJ/mol or kcal/mol; 1 kJ = 0.239 kcal) under standard pH, temperature, and pressure conditions. We generally calculate standard pH, temperature, and pressure conditions at pH 7.0 in biological systems, 25 degrees Celsius, and 100 kilopascals (1 atm pressure), respectively. Note that cellular conditions vary considerably from these standard conditions, and so standard calculated ∆G values for biological reactions will be different inside the cell.

Links to Learning

Entropy: Embrace the Chaos!

Endergonic Reactions and Exergonic Reactions

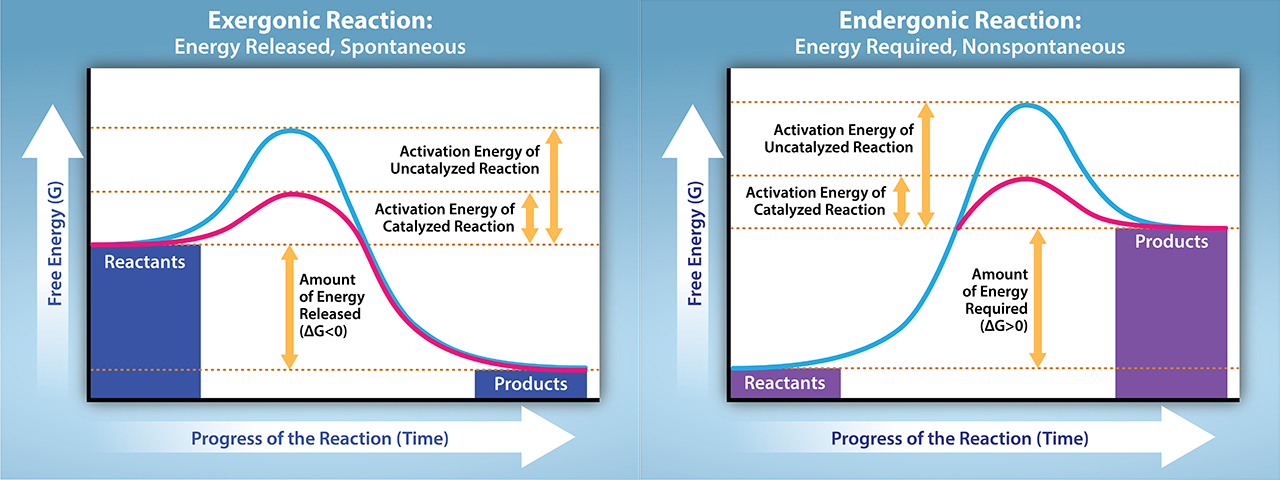

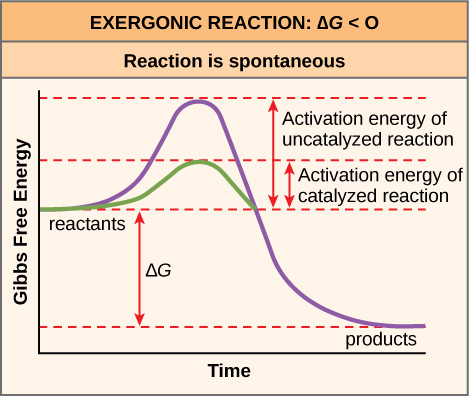

If energy releases during a chemical reaction, then the resulting value from the above equation will be a negative number. In other words, reactions that release energy have a ∆G < 0. A negative ∆G also means that the reaction’s products have less free energy than the reactants, because they gave off some free energy during the reaction. Scientists call reactions that have a negative ∆G and consequently release free energy exergonic reactions. Think: exergonic means energy is exiting the system. We also refer to these reactions as spontaneous reactions, because they can occur without adding energy into the system. Understanding which chemical reactions are spontaneous and release free energy is extremely useful for biologists, because these reactions can be harnessed to perform work inside the cell. We must draw an important distinction between the term spontaneous and the idea of a chemical reaction that occurs immediately. Contrary to the everyday use of the term, a spontaneous reaction is not one that suddenly or quickly occurs. Rusting iron is an example of a spontaneous reaction that occurs slowly, little by little, over time.

If a chemical reaction requires an energy input rather than releasing energy, then the ∆G for that reaction will be a positive value. In this case, the products have more free energy than the reactants. Thus, we can think of the reactions’ products as energy-storing molecules. We call these chemical reactions endergonic reactions, and they are non-spontaneous. An endergonic reaction will not take place on its own without adding free energy.

Let’s revisit the example of the synthesis and breakdown of the food molecule, glucose. Remember that building complex molecules, such as sugars, from simpler ones is an anabolic process and requires energy. Therefore, the chemical reactions involved in anabolic processes are endergonic reactions. Alternatively the catabolic process of breaking sugar down into simpler molecules releases energy in a series of exergonic reactions. Like the rust example above, the sugar breakdown involves spontaneous reactions, but these reactions do not occur instantaneously. Figure 6.8 shows some other examples of endergonic and exergonic reactions. Later sections will provide more information about what else is required to make even spontaneous reactions happen more efficiently.

Visual Connection

Look at each of the processes, and decide if it is endergonic or exergonic.

Look at each of the processes, and decide if it is endergonic or exergonic. In each case, does enthalpy increase or decrease, and does entropy increase or decrease?

An important concept in studying metabolism and energy is that of chemical equilibrium. Most chemical reactions are reversible. They can proceed in both directions, releasing energy into their environment in one direction, and absorbing it from the environment in the other direction (Figure 6.9). The same is true for the chemical reactions involved in cell metabolism, such as the breaking down and building up of proteins into and from individual amino acids, respectively. Reactants within a closed system will undergo chemical reactions in both directions until they reach a state of equilibrium, which is one of the lowest possible free energy and a state of maximal entropy. To push the reactants and products away from a state of equilibrium requires energy. Either reactants or products must be added, removed, or changed. If a cell were a closed system, its chemical reactions would reach equilibrium, and it would die because there would be insufficient free energy left to perform the necessary work to maintain life. In a living cell, chemical reactions are constantly moving towards equilibrium, but never reach it. This is because a living cell is an open system. Materials pass in and out, the cell recycles the products of certain chemical reactions into other reactions, and there is never chemical equilibrium. In this way, living organisms are in a constant energy-requiring, uphill battle against equilibrium and entropy. This constant energy supply ultimately comes from sunlight, which produces nutrients in the photosynthesis process.

Activation Energy

There is another important concept that we must consider regarding endergonic and exergonic reactions. Even exergonic reactions require a small amount of energy input before they can proceed with their energy-releasing steps. These reactions have a net release of energy, but still require some initial energy. Scientists call this small amount of energy input necessary for all chemical reactions to occur the activation energy (or free energy of activation) abbreviated as EA (Figure 6.10).

Why would an energy-releasing, negative ∆G reaction actually require some energy to proceed? The reason lies in the steps that take place during a chemical reaction. During chemical reactions, certain chemical bonds break and new ones form. For example, when a glucose molecule breaks down, bonds between the molecule’s carbon atoms break. Since these are energy-storing bonds, they release energy when broken. However, to get them into a state that allows the bonds to break, the molecule must be somewhat contorted. A small energy input is required to achieve this contorted state. This contorted state is the transition state, and it is a high-energy, unstable state. For this reason, reactant molecules do not last long in their transition state, but very quickly proceed to the chemical reaction’s next steps. Free energy diagrams illustrate the energy profiles for a given reaction. Whether the reaction is exergonic or endergonic determines whether the products in the diagram will exist at a lower or higher energy state than both the reactants and the products. However, regardless of this measure, the transition state of the reaction exists at a higher energy state than the reactants, and thus, EA is always positive.

Link to Learning

Watch an animation of the move from free energy to transition state from Shomu’s Biology.

From where does the activation energy that chemical reactants require come? The activation energy’s required source to push reactions forward is typically heat energy from the surroundings. Heat energy (the total bond energy of reactants or products in a chemical reaction) speeds up the molecule’s motion, increasing the frequency and force with which they collide. It also moves atoms and bonds within the molecule slightly, helping them reach their transition state. For this reason, heating a system will cause chemical reactants within that system to react more frequently. Increasing the pressure on a system has the same effect. Once reactants have absorbed enough heat energy from their surroundings to reach the transition state, the reaction will proceed.

The activation energy of a particular reaction determines the rate at which it will proceed. The higher the activation energy, the slower the chemical reaction. The example of iron rusting illustrates an inherently slow reaction. This reaction occurs slowly over time because of its high EA. Additionally, burning many fuels, which is strongly exergonic, will take place at a negligible rate unless sufficient heat from a spark overcomes their activation energy. However, once they begin to burn, the chemical reactions release enough heat to continue the burning process, supplying the activation energy for surrounding fuel molecules. Like these reactions outside of cells, the activation energy for most cellular reactions is too high for heat energy to overcome at efficient rates. In other words, in order for important cellular reactions to occur at appreciable rates (number of reactions per unit time), their activation energies must be lowered (Figure 6.10). Scientist refer to this as catalysis. This is a very good thing as far as living cells are concerned. Important macromolecules, such as proteins, DNA, and RNA, store considerable energy, and their breakdown is exergonic. If cellular temperatures alone provided enough heat energy for these exergonic reactions to overcome their activation barriers, the cell’s essential components would disintegrate.

Visual Connection

If no activation energy were required to break down sucrose (table sugar), would you be able to store it in a sugar bowl?