5.4 Bulk Transport

Key Concepts

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe endocytosis, including phagocytosis, pinocytosis, and receptor-mediated endocytosis

- Understand the process of exocytosis

In addition to moving small ions and molecules through the membrane, cells also need to remove and take in larger molecules and particles (see Table 5.2 for examples at the bottom of this page). Some cells are even capable of engulfing entire unicellular microorganisms. You might have correctly hypothesized that when a cell uptakes and releases large particles, it requires energy. A large particle, however, cannot pass through the membrane, even with energy that the cell supplies.

Endocytosis

Endocytosis is a type of active transport that moves particles, such as large molecules, parts of cells, and even whole cells, into a cell. There are different endocytosis variations, but all share a common characteristic: the cell’s plasma membrane invaginates, forming a pocket around the target particle. The pocket pinches off, resulting in the particle containing itself in a newly created intracellular vesicle formed from the plasma membrane.

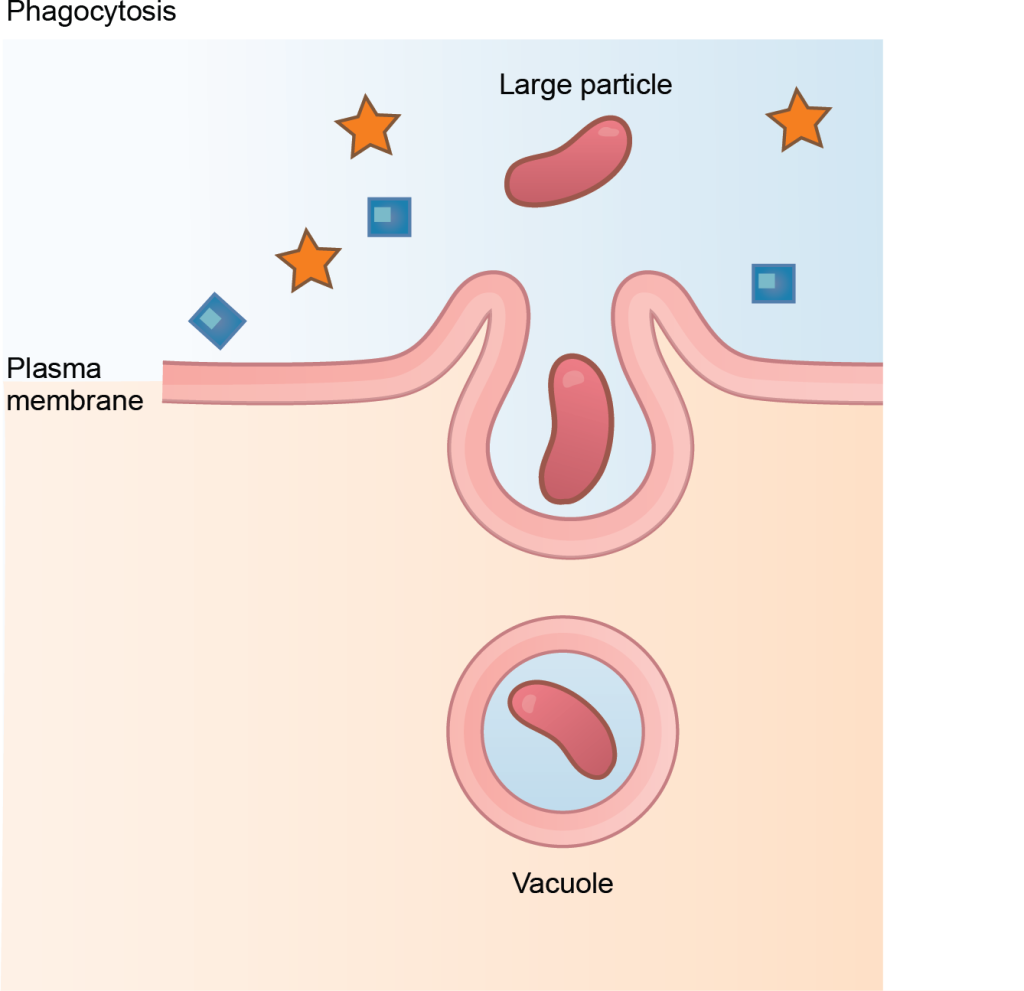

Phagocytosis

Phagocytosis (the condition of “cell eating”) is the process by which a cell takes in large particles, such as other cells or relatively large particles. For example, when microorganisms invade the human body, a type of white blood cell, a neutrophil, will remove the invaders through this process, surrounding and engulfing the microorganism, which the neutrophil then destroys (Figure 5.21).

In preparation for phagocytosis, a portion of the plasma membrane’s inward-facing surface becomes coated with the protein clathrin, which stabilizes this membrane’s section. The membrane’s coated portion then extends from the cell’s body and surrounds the particle, eventually enclosing it. Once the vesicle containing the particle is enclosed within the cell, the clathrin disengages from the membrane and the vesicle merges with a lysosome for breaking down the material in the newly formed compartment (endosome). When accessible nutrients from the vesicular contents’ degradation have been extracted, the newly formed endosome merges with the plasma membrane and releases its contents into the extracellular fluid. The endosomal membrane again becomes part of the plasma membrane.

Link to Learning

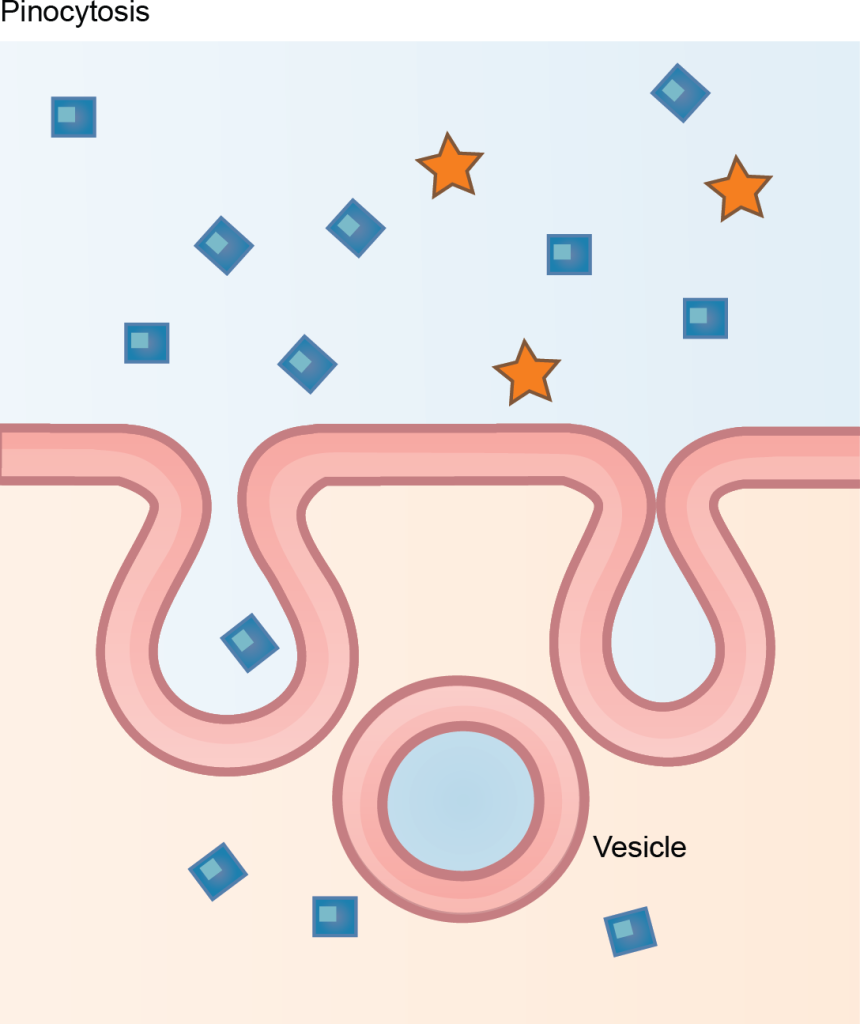

Pinocytosis

A variation of endocytosis is pinocytosis. This literally means “cell drinking”. Discovered by Warren Lewis in 1929, this American embryologist and cell biologist described a process whereby he assumed that the cell was purposefully taking in extracellular fluid. In reality, this is a process that takes in molecules, including water, which the cell needs from the extracellular fluid. Pinocytosis results in a much smaller vesicle than does phagocytosis, and the vesicle does not need to merge with a lysosome (Figure 5.22).

A variation of pinocytosis is potocytosis. This process uses a coating protein, caveolin, on the plasma membrane’s cytoplasmic side, which performs a similar function to clathrin. The cavities in the plasma membrane that form the vacuoles have membrane receptors and lipid rafts in addition to caveolin. The vacuoles or vesicles formed in caveolae (singular caveola) are smaller than those in pinocytosis. Potocytosis brings small molecules into the cell and transports them through the cell for their release on the other side, a process we call transcytosis. In some cases, the caveolae deliver their cargo to membranous organelles like the ER.

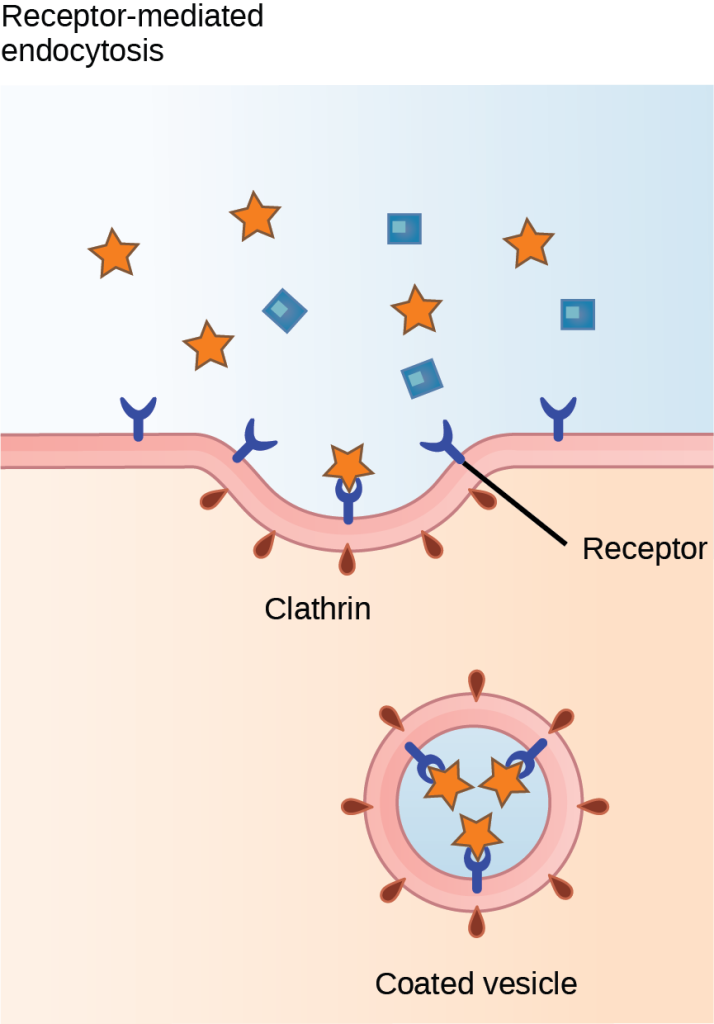

Receptor-mediated Endocytosis

A targeted variation of endocytosis employs receptor proteins in the plasma membrane that have a specific binding affinity for certain substances (Figure 5.23).

In receptor-mediated endocytosis, as in phagocytosis, clathrin attaches to the plasma membrane’s cytoplasmic side. If a compound’s uptake is dependent on receptor-mediated endocytosis and the process is ineffective, the material will not be removed from the tissue fluids or blood. Instead, it will stay in those fluids and increase in concentration. The failure of receptor-mediated endocytosis causes some human diseases. For example, receptor mediated endocytosis removes low density lipoprotein or LDL (or “bad” cholesterol) from the blood. In the human genetic disease familial hypercholesterolemia, the LDL receptors are defective or missing entirely. People with this condition have life-threatening levels of cholesterol in their blood, because their cells cannot clear LDL particles.

Although receptor-mediated endocytosis is designed to bring specific substances that are normally in the extracellular fluid into the cell, other substances may gain entry into the cell at the same site. Flu viruses, diphtheria, and cholera toxin all have sites that cross-react with normal receptor-binding sites and gain entry into cells.

Link to Learning

See receptor-mediated endocytosis in action in this video

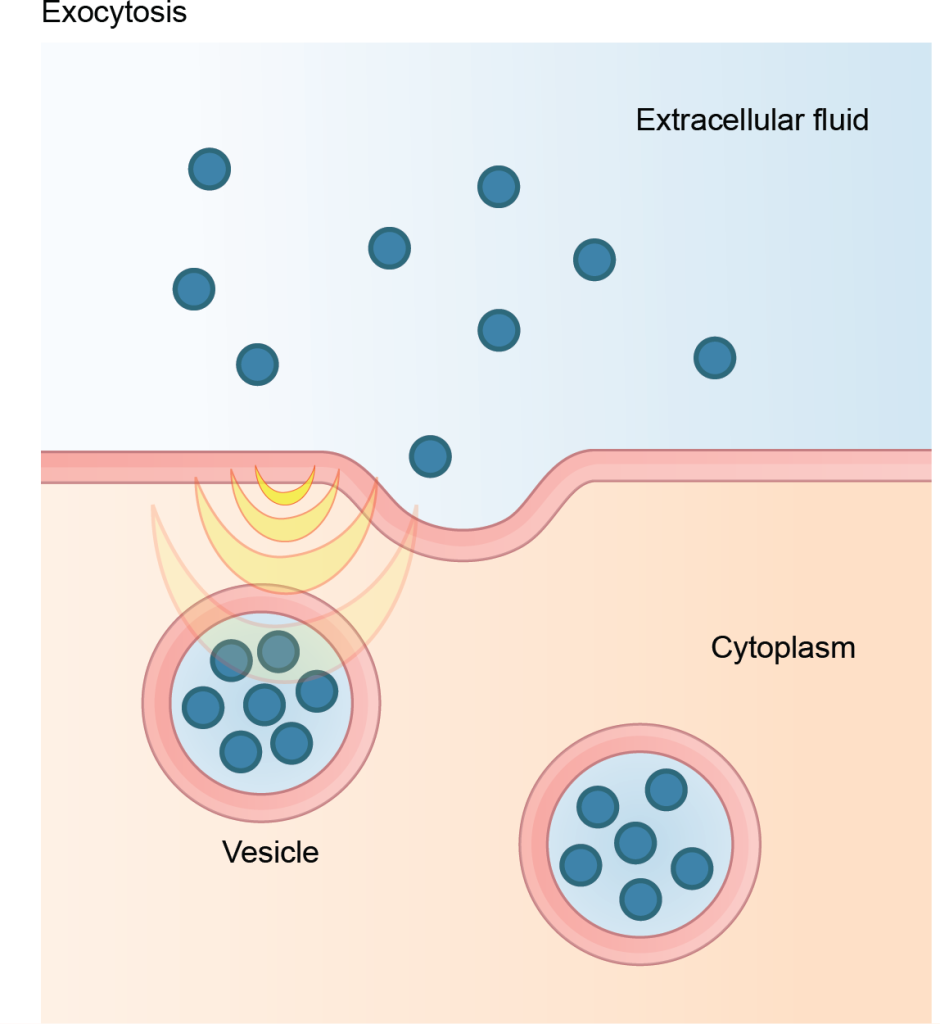

Exocytosis

The reverse process of moving material into a cell is the process of exocytosis. Exocytosis is the opposite of the processes we discussed above in that its purpose is to expel material from the cell into the extracellular fluid. Waste material is enveloped in a membrane and fuses with the plasma membrane’s interior. This fusion opens the membranous envelope on the cell’s exterior, and the waste material expels into the extracellular space (Figure 5.24). Other examples of cells releasing molecules via exocytosis include extracellular matrix protein secretion and neurotransmitter secretion into the synaptic cleft by synaptic vesicles.

Link to Learning

| Transport Method | Active/Passive | Material Transported |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion | Passive | Small-molecular weight material |

| Osmosis | Passive | Water |

| Facilitated transport/diffusion | Passive | Sodium, potassium, calcium, glucose |

| Primary active transport | Active | Sodium, potassium, calcium |

| Secondary active transport | Active | Amino acids, lactose |

| Phagocytosis | Active | Large macromolecules, whole cells, or cellular structures |

| Pinocytosis and potocytosis | Active | Small molecules (liquids/water) |

| Receptor-mediated endocytosis | Active | Large quantities of macromolecules |