Key Concepts

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- List the components of the endomembrane system

- Recognize the relationship between the endomembrane system and its functions

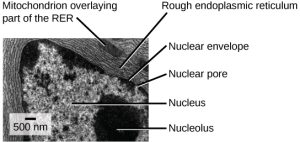

The endomembrane system (endo = “within”) is a group of membranes and organelles (Figure 4.18) in eukaryotic cells that works together to modify, package, and transport lipids and proteins. It includes the nuclear envelope, lysosomes, and vesicles, which we have already mentioned, and the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, which we will cover shortly. Although not technically within the cell, the plasma membrane is included in the endomembrane system because, as you will see, it interacts with the other endomembranous organelles. The endomembrane system does not include either mitochondria or chloroplast membranes.

Visual Connection

If a peripheral membrane protein were synthesized in the lumen (inside) of the ER, would it end up on the inside or outside of the plasma membrane?

The Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Figure 4.18) is a series of interconnected membranous sacs and tubules that collectively modifies proteins and synthesizes lipids. However, these two functions take place in separate areas of the ER: the rough ER and the smooth ER, respectively.

We call the ER tubules’ hollow portion the lumen or cisternal space. The ER’s membrane, which is a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins, is continuous with the nuclear envelope.

Rough ER

Scientists have named the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) as such because the ribosomes attached to its cytoplasmic surface give it a studded appearance when viewing it through an electron microscope (Figure 4.19).

Ribosomes transfer their newly synthesized proteins into the RER’s lumen where they undergo structural modifications, such as folding or acquiring side chains. These modified proteins incorporate into cellular membranes—the ER or the ER’s or other organelles’ membranes. The proteins can also secrete from the cell (such as protein hormones, enzymes). The RER also makes phospholipids for cellular membranes.

If the phospholipids or modified proteins are not destined to stay in the RER, they will reach their destinations via transport vesicles that bud from the RER’s membrane (Figure 4.18).

Since the RER is engaged in modifying proteins (such as enzymes, for example) that secrete from the cell, you would be correct in assuming that the RER is abundant in cells that secrete proteins. This is the case with liver cells, for example.

Smooth ER

The smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER) is continuous with the RER but has few or no ribosomes on its cytoplasmic surface (Figure 4.18). SER functions include synthesis of carbohydrates, lipids, and steroid hormones; detoxification of medications and poisons; and storing calcium ions.

In muscle cells, a specialized SER, the sarcoplasmic reticulum, is responsible for storing calcium ions that are needed to trigger the muscle cells’ coordinated contractions.

Link to Learning

You can watch an excellent animation of the endomembrane system here from Richochet Science

Career Connection

Cardiologist

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States. This is primarily due to our sedentary lifestyle and our high trans-fat diets.

Heart failure is just one of many disabling heart conditions. Heart failure does not mean that the heart has stopped working. Rather, it means that the heart can’t pump with sufficient force to transport oxygenated blood to all the vital organs. Left untreated, heart failure can lead to kidney failure and other organ failure.

Cardiac muscle tissue comprises the heart’s wall. Heart failure occurs when cardiac muscle cells’ endoplasmic reticula do not function properly. As a result, an insufficient number of calcium ions are available to trigger a sufficient contractile force.

Cardiologists (cardi- = “heart”; -ologist = “one who studies”) are doctors who specialize in treating heart diseases, including heart failure. Cardiologists can diagnose heart failure via a physical examination, results from an electrocardiogram (ECG, a test that measures the heart’s electrical activity), a chest X-ray to see whether the heart is enlarged, and other tests. If the cardiologist diagnoses heart failure, they will typically prescribe appropriate medications and recommend a reduced table salt intake and a supervised exercise program.

The Golgi Apparatus

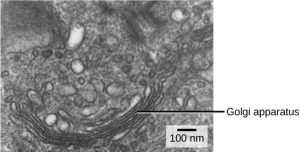

We have already mentioned that vesicles can bud from the ER and transport their contents elsewhere, but where do the vesicles go? Before reaching their final destination, the lipids or proteins within the transport vesicles still need sorting, packaging, and tagging so that they end up in the right place. Sorting, tagging, packaging, and distributing lipids and proteins takes place in the Golgi apparatus (also called the Golgi body), a series of flattened membranous sacs (Figure 4.20).

The side of the Golgi apparatus that is closer to the ER is called the cis face. The opposite side is the trans face. The transport vesicles that formed from the ER travel to the cis face, fuse with it, and empty their contents into the Golgi apparatus’ lumen. As the proteins and lipids travel through the Golgi, they undergo further modifications that allow them to be sorted. The most frequent modification is adding short sugar molecule chains. These newly modified proteins and lipids then tag with phosphate groups or other small molecules in order to travel to their proper destinations.

Finally, the modified and tagged proteins are packaged into secretory vesicles that bud from the Golgi’s trans face. While some of these vesicles deposit their contents into other cell parts where they will be used, other secretory vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane and release their contents outside the cell.

In another example of form following function, cells that engage in a great deal of secretory activity (such as salivary gland cells that secrete digestive enzymes or immune system cells that secrete antibodies) have an abundance of Golgi.

In plant cells, the Golgi apparatus has the additional role of synthesizing polysaccharides, some of which are incorporated into the cell wall and some of which other cell parts use.

Career Connection

Geneticist

Many diseases arise from genetic mutations that prevent synthesizing critical proteins. One such disease is Lowe disease (or oculocerebrorenal syndrome, because it affects the eyes, brain, and kidneys). In Lowe disease, there is a deficiency in an enzyme localized to the Golgi apparatus. Children with Lowe disease are born with cataracts, typically develop kidney disease after the first year of life, and may have intellectual disabilities.

A mutation on the X chromosome causes Lowe disease. The X chromosome is one of the two human sex chromosomes, as these chromosomes determine a person’s sex. Females possess two X chromosomes while males possess one X and one Y chromosome. In females, the genes on only one of the two X chromosomes are expressed. Females who carry the Lowe disease gene on one of their X chromosomes are carriers and do not show symptoms of the disease. However, males only have one X chromosome and the genes on this chromosome are always expressed. Therefore, males will always have Lowe disease if their X chromosome carries the Lowe disease gene. Geneticists have identified the mutated gene’s location, as well as many other mutation locations that cause genetic diseases. Through prenatal testing, a pregnant person can find out if the fetus they are carrying may be afflicted with one of several genetic diseases.

Geneticists analyze prenatal genetic test results and may counsel pregnant people on available options. They may also conduct genetic research that leads to new drugs or foods, or perform DNA analyses for forensic investigations.

Lysosomes

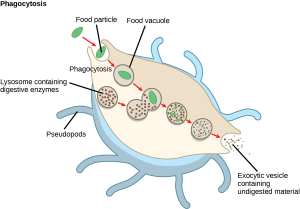

In addition to their role as the digestive component and organelle-recycling facility of animal cells, lysosomes are part of the endomembrane system. Lysosomes also use their hydrolytic enzymes to destroy pathogens (disease-causing organisms) that might enter the cell. A good example of this occurs in macrophages, a group of white blood cells which are part of your body’s immune system. In a process that scientists call phagocytosis or endocytosis, a section of the macrophage’s plasma membrane invaginates (folds in) and engulfs a pathogen. The invaginated section, with the pathogen inside, then pinches itself off from the plasma membrane and becomes a vesicle. The vesicle fuses with a lysosome. The lysosome’s hydrolytic enzymes then destroy the pathogen (Figure 4.21).

Link to Learning

Watch Eukaryopolis – The City of Animal Cells, a video about eukaryotic cells from Crash Course Biology