9 Chapter 8: Cognitive and Other Disorders

Tracy Everitt; Brittany Yantha; Megan Davies; Sayuri Omori; and Laurie Wadsworth

Chapter 8 Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this chapter, students will be able to:

Learning Objectives

- Explain cognitive changes that commonly occur in late adulthood.

- Discuss the impact of aging on memory.

- Explain how age impacts cognitive function.

- Understand the symptoms and effective management strategies associated with Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Understand the symptoms and effective management strategies associated with Parkinson’s Disease.

Just like the rest of our bodies, our brains change as we age. Most people notice some slowed thinking and occasional problems with remembering. There are numerous stereotypes regarding older adults as being forgetful and confused, but what does the research on memory and cognition in late adulthood actually reveal? In this section, we will focus on the impact of aging on memory, how age impacts cognitive function, and abnormal memory loss due to Alzheimer‘s disease, delirium, Parkinson‘s disease, and dementia.

8.1 Aging and the Mind

As people age, there is generally a slowing of nerve firing throughout the body, which results in a slowing of processing information or performing tasks. Older adults may not be able to think or perform tasks as quickly as they could before. They may show signs of forgetfulness, which can be normal. However, when there seem to be many memory problems, and forgetfulness seems to be increasing, this may be a sign of a more significant problem.

Changes in Attention in Late Adulthood

Divided attention has usually been associated with significant age-related declines in performing complex tasks. For example, older adults show significant impairments in attentional tasks such as looking at a visual cue at the same time as listening to an auditory cue because it requires dividing or switching attention among multiple inputs. The tasks on which older adults show impairments tend to require flexible control of attention, a cognitive function associated with the frontal lobes. These tasks improve with training and can be strengthened (Glisky, 2007).

Figure 8.1.1: During late adulthood, memory and attention decline, but continued efforts to learn and engage in cognitive activities can minimize aging effects on cognitive development.

Figure 8.1.1: During late adulthood, memory and attention decline, but continued efforts to learn and engage in cognitive activities can minimize aging effects on cognitive development.

Changes in Sensory Functions

Aging may create small decrements in the sensitivity of the senses. These small changes can compound to the extent that a person has a more challenging time hearing or seeing, and that information will not be stored in memory. This is a critical point because many older people assume that if they cannot remember something, it is because their memory is poor. In fact, it may be that the information was never seen or heard.

The Working Memory

Throughout aging, older adults may experience increased difficulty using techniques to help recall details (I.e., using a planner, mnemonic devices, etc.) (Berk, 2007). Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity responsible for temporarily holding information available for processing. As people age, the working memory loses some of its capacity. This makes it more difficult to concentrate on more than one thing at a time or remember an event’s details. However, people often compensate for this by writing down information and avoiding situations where there is too much going on at once to focus on a particular cognitive task.

Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory involves the storage of information for long periods of time. Retrieving such information depends on how well it was learned in the first place rather than how long it has been stored. Younger adults rely more on mental rehearsal strategies to store and retrieve information. Older adults focus more on external cues such as familiarity and context to recall information (Berk, 2007). If information is stored effectively, an older person may remember facts, events, names, and other types of information stored in long-term memory throughout life. The long-term memory of adults of all ages seems to be similar when they are asked to recall the names of teachers or classmates. Older adults remember more about their early adulthood and adolescence than about middle adulthood (Berk, 2007).

8.2 Temporary Cognitive Changes

There may be temporary changes in mental function that come about suddenly. Sudden changes in mental functioning and personality can indicate a disease process. Changes in cognitive function that appear suddenly or are temporary can result from dehydration, a urinary tract infection, fever, brain infection such as meningitis, a head injury, stroke, low blood sugar levels, alcohol or substance use, and medication interactions or side effects.

Delirium

Delirium is a common and serious complication in hospitalized older people. Delirium, also known as acute confused state, is an organically caused decline from a previous baseline level of mental function that develops over a brief period, typically hours to days (Geirsdóttir & Bell, 2021). It is more common in older adults, but can easily be confused with a few psychiatric disorders or chronic organic brain syndromes because of many overlapping signs and symptoms in common with dementia, depression, psychosis, etc. All hospital inpatients aged 65 and older with known cognitive impairment or experiencing serious illness or injury should be recognized as at elevated risk for delirium. Delirium often results in difficulties understanding information, including disturbing misperceptions and hallucinations. These experiences can result in fear and distress for the patient.

Delirium can complicate acute illness, surgery, or injury. Among older adults, delirium occurs in 15-53% of post-surgical patients, 70-87% of ICU patients, and up to 60% of nursing homes or post-acute care settings (Geirsdóttir & Bell, 2021). No drugs are demonstrated to either prevent or treat delirium, but using multicomponent multidisciplinary prevention programs can reduce delirium by 30-50% in hospital settings (Geirsdóttir & Bell, 2021). Poor food and fluid intake are important precipitating and perpetuating factors for delirium. Maintaining food and fluid intake is a central strategy within delirium prevention programs. However, this can be challenging in people with cognitive impairment and/or severe illness. Adequate mealtime preparation, including the relief of pain and nausea, timely toileting and appropriate positioning, may require coordinated assistance from other team members before meal delivery. Nursing staff need to be present during mealtimes to provide encouragement, anticipate and instigate assistance and advocate for their patients by discouraging other team members from interrupting patients during their meals (Geirsdóttir & Bell, 2021). Food and fluid intake should also be monitored and documented at every meal to allow early identification of changes in food intake among high-risk groups. Mealtimes have important social meaning and serve as an orientating stimulus to help with delirium prevention. Opportunities for shared dining experiences and inviting family presence at mealtimes can help normalize the mealtime experience and may improve intake.

Urinary Tract Infections

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a type of infection common among older people. A urinary tract infection is usually caused by bacteria entering the urinary tract via the urethra – the tube that allows the passage of urine from the bladder to outside the body. If an older person has a sudden and unexplained change in their behaviour, such as increased confusion, agitation, or withdrawal, this may be because of a UTI. If a person with a memory impairment or dementia has a UTI, this can cause sudden and severe confusion, known as ‘delirium.’ The person may not be able to communicate how they feel; therefore, it is helpful to be familiar with the symptoms of UTIs and seek medical help to ensure they get the correct treatment.

There are conflicting theories on the connection between UTIs and delirium. Some research suggests that delirium associated with UTIs results from inflammation from the UTI, or delirium may contribute to UTIs or other health changes may contribute to increased risk factors for both UTIs and delirium (Dutta et al., 2022). Other research has found that the association between UTIs and delirium is methodologically flawed due to poor case definition for UTI and delirium, or inadequate control of confounding factors which introduces significant bias (Mayne et al., 2019).

Question: Has recent research proven or disproved the theory that there is a relationship between UTIs and delirium, especially among older adults?

It is also important to be aware that any infection could speed up the progression of dementia, so all infections should be identified and treated quickly. If treated with the right antibiotics, UTIs normally cause no further problems, and the infection soon passes (Alzheimer’s Society, n.d.).

The Role of Enteral Feeding

Maintaining adequate nutrition and hydration plays a vital role in preventing and treating delirium and other conditions. It may be appropriate to consider enteral feeding via a nasogastric tube if the patient is unable to eat and drink enough to meet their nutritional needs. Functional dysphagia is a common side effect of delirium. Enteral feeding can improve intake and prevent poor clinical outcomes. However, the risks of tube feeding, and its placement must be weighed against the benefits of adequate nutrition. Enteral feeding may cause additional stress for the patient.

Decision-making about enteral feeding for a patient with delirium is complex and must be individualized in line with patient goals and the prognosis of the underlying conditions. Appropriate patient positioning remains important to reduce the risk of aspiration, such as sitting upright at a 45-degree angle (Park et al., 2013). In addition, using bolus rather than continuous feeds may be more appropriate to reduce restraint utilization and address limitations to mobility. Strategies to reduce the risk of dislodgement include using fiddle blankets and other distracting activities. If it is safe, continuing to provide even tiny amounts of oral intake when the patient is more alert and able to sit upright will help promote swallow function and appetite, provide pleasure, and maintain meaningful routines. The feeding tube should be removed as soon as adequate oral intake can be re-established (Geirsdóttir & Bell, 2021).

8.3 Permanent Cognitive Changes

Dementia

Dementia is the umbrella category used to describe the general long-term and often gradual decrease in the ability to think and remember that affects a person’s daily functioning. The manual used to help classify and diagnose mental disorders, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-V, classifies dementia as “major neurocognitive disorder, with milder symptoms classified as “mild cognitive impairment,” although the term dementia is still in common use. Common symptoms of dementia include emotional problems, difficulties with language, and decreased motivation. A person’s consciousness is usually not affected. In North America, about 10% of people develop the disorder at some point, and it becomes more common with age. As more people are living longer, dementia is becoming more common in the population.

Dementia refers to severely impaired judgment, memory, or problem-solving ability. It can occur before old age and is not inevitable, even among the very old. Numerous diseases and circumstances can cause dementia, resulting in similar general symptoms of impaired judgment, etc. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia and is incurable, but there are also nonorganic causes of dementia that can be prevented. Malnutrition, alcoholism, depression, and mixing medications can also result in symptoms of dementia. If these causes are properly identified, they can be treated. Cerebral vascular disease can also reduce cognitive functioning.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease that causes problems with memory, thinking and behaviour, and is the most common cause of dementia. Symptoms usually develop slowly and worsen over time, becoming severe enough to interfere with daily tasks (Alzheimer’s Association, n.d.). During the preliminary stages, memory loss is mild. In later stages it becomes more severe, and individuals lose the ability to carry on a conversation and respond to their environment. Alzheimer’s is not a normal part of aging, but increasing age is the greatest known risk factor. On average, a person with Alzheimer’s lives 4-8 years after diagnosis but can live as long as 20 years, depending on other factors (Alzheimer’s Association, n.d.).

The most common early symptom is difficulty remembering recent events or newly learned information. Alzheimer’s changes typically begin in the part of the brain that affects learning. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems with language, disorientation (including easily getting lost), mood swings, loss of motivation, not managing self-care, and behavioural issues. In the initial stages, memory loss is mild, but with late-stage Alzheimer’s, individuals lose the ability to carry on a conversation and respond to their environment. People with memory loss or other signs of Alzheimer’s may find it hard to recognize that they have a problem. Signs of dementia may be more evident to family members or friends. Anyone experiencing dementia-like symptoms should see a doctor as soon as possible. Earlier diagnosis and intervention methods are improving dramatically, and treatment options and sources of support can improve quality of life.

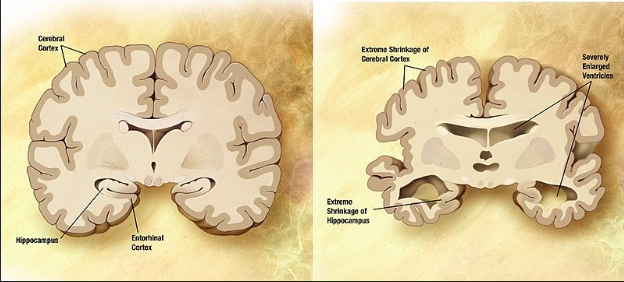

Figure 9.3.2: Alzheimer’s disease is not simply part of the aging process. It is a disease with physiological symptoms and decay in the brain.

Microscopic changes in the brain begin long before the first signs of memory loss. Scientists believe Alzheimer’s disease impedes parts of a brain cells’ functional ability. Scientists are unsure where the trouble starts, but issues in one part of the cell cause issues in other areas. As damage spreads, cells lose their ability to do their jobs and eventually die, causing irreversible changes in the brain Two abnormal structures called plaques and tangles are prime suspects in damaging and killing nerve cells. Plaques are deposits of a protein fragment that build up in the spaces between nerve cells. Tangles are twisted fibers of another protein that build up inside cells. Microscopic changes lead to physically observable changes, as depicted in Figure 9.3.2. Autopsy studies show that most people develop some plaques and tangles as they age; however, those with Alzheimer’s tend to develop far more and in a predictable pattern, beginning in the areas important for memory and then spreading to other regions. The destruction and death of nerve cells causes memory failure, personality changes, problems carrying out daily activities and other symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s has no cure, but treatments can temporarily slow the worsening of dementia symptoms and improve the quality of life for those with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers.

A person with Alzheimer’s needs special care, providing a safe environment. They may wander and end up in an unknown place with no memory of who they are, how they got to where they are, or how to return home. It is also important to prevent dangerous events such as fires, as a person with Alzheimer’s may begin to cook and forget they have food on the stove. Writing lists and labelling objects throughout the house may also be helpful to remind a patient with Alzheimer’s disease what the objects are. It may even helpful to place a note on the mirror with the patient’s name or a label such as “Myself” if they are at the point where they no longer remember who they are. Caregivers should remember to be patient and encouraging and find the things that seem to bring comfort and do these things with their patients. Many patients with Alzheimer’s enjoy music, and caregivers or relatives can try playing some to help their patients relax and find enjoyment.

Nutrition Implications for Alzheimer’s

As memory loss is the primary cognitive impairment caused by Alzheimer‘s disease, forgetting to prepare food or attend to one‘s nutritional needs is common among those with Alzheimer‘s. Attention difficulties can cause an inability to complete food preparation or sit throughout a meal. Alzheimer‘s also causes a decrease in sensory reception. The decreased olfactory sense can impair a person‘s enjoyment of foods and make them want to eat less.

Kitchen safety can have new challenges for folks with cognitive changes. Some things caretakers can do to improve kitchen safety include supervision while food is being made, making sure spoiled food is promptly disposed of, and appliances are turned off or disabled if necessary (Reitman Center Team, 2019). People with cognitive changes may forget about kitchen and food safety, leading to accidents or food borne illnesses.

Example

Sundowning

Late afternoon and early evening can be difficult for some people with Alzheimer’s disease. They may experience sundowning—restlessness, agitation, irritability, or confusion that can begin or worsen as daylight begins to fade—often just when tired caregivers need a break. Sundowning can happen at any stage of dementia but is more common during the middle stage and later stages (Alzheimer’s Society, n.d.). Although the exact cause of sundowning is unknown, these changes result from the disease’s impact on the brain. The mental and physical exhaustion from trying to keep up with an unfamiliar environment may contribute to difficulties in sleep. Disorientation due to the inability to separate dreams from reality is another factor that may contribute to this phenomenon of sundowning.

Some research suggests that a low dose of melatonin — a naturally occurring hormone that induces sleepiness — alone or in combination with exposure to bright light during the day may help ease sundowning. Tips that may help to manage sundowning include scheduling activities in the morning when the person with dementia is more alert rather than at night, encouragement of a regular routine of waking up and going to bed, when possible, and including walks or time outside in the sunlight.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive and incurable disease of the brain (according to National Institute of Aging) resulting in permanent changes. This condition results from the depletion of dopamine in the brain causing abnormalities in cells deep within the brain tissue. People with Parkinson’s have difficulty initiating movement, such as walking, and have tremors, making it difficult to perform daily tasks such as feeding and dressing. Muscles will become stiff, and the person may have a shuffling gait or be unable to walk. Dementia may occur as Parkinson’s progresses. The cause of Parkinson’s disease, and the depletion of dopamine, is unknown, but treatments for this condition focus on replacing dopamine levels in the brain.

Cardinal signs of someone experiencing Parkinson’s include tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. As Parkinson’s disease progresses in a patient, it is common to see them experience dysphasia, soft monotone speech, and changes in gastrointestinal motility. Being patient and encouraging is important when caring for patients with Parkinson’s. It is frustrating for them to be unable to care for themselves. Encourage them to do as much as possible and assist them with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) as needed.

Nutrition Implications for Parkinson’s

Nutritional implications for those experiencing Parkinson’s disease include increased risk for weight loss and malnutrition due to extra movements, causing the body to burn more calories. General recommendations to combat weight loss include increasing daily protein and energy intake and fibre and fluid intake to treat and prevent constipation. It is important to remember to prepare food that is easier for the patient to handle. Using adaptive eating utensils, plates, and cups can help make the eating experience more pleasurable and successful for the patient.

This chapter is adapted from ‘Lifespan Development’ by Lumen Learning: https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/lumenlife/

Creative Commons Attribution: BY

References

Alzheimer’s Association. (n.d.). What is Alzheimer’s? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers

Alzheimer’s Society. (n.d.). Sundowning and Dementia. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/symptoms/sundowning

Alzheimer’s Society. (n.d.). UTIs and Delirium. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/daily-living/UTIs-and-delirium

Dutta, C., Pasha, K., Paul, S., Abbas, M.S., Nassar, S.T., Tasha, T., Desai, A., Bajgain, A., Ali, A., & Mohammed, L. (2022, December 8). Urinary Tract Infection Induced Delirium in Elderly Patients: A Systematic Review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9827929/

Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. p. 221., FN Park DC, Gutchess AH. Cognitive aging and everyday life. In: Park D, Schwarz N, editors. Cognitive Aging: A Primer. Psychology Press; Philadelphia, PA: 2000. p. 217.

Geirsdóttir, Ó. G., & Bell, J. J. (2021). Interdisciplinary Nutritional Management and Care for Older Adults: An Evidence-Based Practical Guide for Nurses (p. 271). Springer Nature.

Glisky EL. Changes in Cognitive Function in Human Aging. In: Riddle DR, editor. Brain Aging: Models, Methods, and Mechanisms. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2007. Chapter 1. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK3885/

Leahy, W., Fuzy, J., & Grafe, J. (2013). Providing home care: A textbook for home health aides (4th ed.). Albuquerque, NM: Hartman.

Mauk, K. L. (2008, June/July). Myths of aging. ARN Network, 6-7. Retrieved from http://www.rehabnurse.org/pdf/GeriatricsMyths.pdf

Mayne, S., Bowden, A., Sundvall, P.D., & Gunnarsson, R. (2019, February 4). The scientific evidence for a potential link between confusion and urinary tract infection in the elderly is still confusing – a systematic literature review. https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-019-1049-7

Oregon Department of Human Services. (2012, June). Myths and stereotypes of aging (Publication DHS 9570). Retrieved from http://www.oregon.gov/dhs/apd-dd-training/EQC%20Training%20Documents/Myths%20and%20Stereotypes%20of%20Aging.pdf

Reitman Center Team. (2019, October 11). Cooking and dementia: challenges, concerns and strategies from the caregivers’ perspective. https://www.dementiacarers.ca/cooking-and-dementia-challenges-concerns-strategies-from-the-caregivers-perspective/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging. (2011, November). Biology of aging: Research today for a healthier tomorrow (Publication No. 11-7561). Retrieved from http://www.nia.nih.gov/sites/default/files/biology_of_aging.pdf

Media Attributions

- Screen Shot 2022-12-20 at 4.39.24 PM

- Screen Shot 2022-12-20 at 4.39.48 PM