11 Chapter 10: Social Variables Influencing Nutrition

Tracy Everitt; Megan Davies; and Sayuri Omori

Chapter 10 Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this chapter, students will be able to:

Learning Objectives

- Describe the individual factors that may impact one’s nutritional status.

- List possible health factors that may impact one’s nutritional status.

- Describe psychosocial factors and changes that may impact one’s nutritional status.

- Understand the impacts of social isolation and loneliness on food intake for older adults as well as the increased risk for the LGBTQ community.

Introduction

The period of late adulthood, which starts around age 65, is characterized by many changes and ongoing personal development. Older adults face profound physical, cognitive, and social changes, and many find strategies to adjust successfully. Demographic and socioeconomic factors can impact the social aspects of aging and food intake. Socially, older adults adjust to changes, such as retiring from work or the death of a spouse or friends. Family relationships may change but continue to be a part of their lives, especially relationships with siblings, children, and grandchildren. Friendships, an important source of social support, are valued and needed in late adulthood. Social isolation and loneliness can affect mental and physical health and have significant nutritional impacts.

Example of a Social Framework for Nutrition and Healthy Aging

Figure 10.1: A social framework that outlines the sectors and components involved in nutrition and healthy aging.

Source: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/health_equity/addresssingtheissue.html.

The Social Framework in Figure 10.1 describes factors that shape a person’s food and physical activity choices. The framework identifies four layers of influence: individual factors, settings, sectors, and social and cultural norms and values. Practitioners often focus on personal factors during clinical care and prescribe a course of action for the individual. The Social Framework reminds us that a whole host of factors often influences individual choices and that effective guidance respects and considers these layers of influence. Health outcomes are influenced by individual factors that determine dietary intake, physical activity, and lifestyle issues, within the context off settings, sectors, and social and cultural norms and values.

10.1 Individual Factors

Age & Gender

Age does not necessarily predict food and nutritional status, however, there are established nutrient recommendations by age and gender (Dietary Reference Intakes or DRIs). The recommendations are provided by age and gender and some nutrients have different requirements for adults aged 51-70 and over 71. DRIs consider that males tend to have more muscle mass than females, so some nutrient requirements, such as energy, are higher in males.

Socioeconomic Status

Other individual factors such as socioeconomic status, disability and race or ethnicity impact health and wellness. Research suggests that a high level of income, good physical and mental health, access to transportation and social contacts are resources that support healthy eating habits. Lower levels of economic resources are associated with a greater risk of experiencing hunger and food insufficiency. Some research suggests that it costs more to eat healthily; thus, low income may restrict the quantity and nutritional quality of the food purchased. Research also shows that health problems related to inadequate nutrition are more prevalent in rural areas, where transportation to and from shops is a structural barrier to obtaining adequate food. Thus, higher economic status and access to a car may be resources that may contribute to older people having a more varied diet.

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity is limited or uncertain access to adequate food. The uncertainty is chronic- it is not because one forgot to bring lunch money today, but instead there is a persistent uncertainty due to a lack of resources. Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life (World Food Summit, 1996). In North America, older adults are vulnerable to food insecurity. Many individual factors influence the risk of food insecurity.

Some older adults are at higher risk for food insecurity than others. Research shows that food insecurity rates tend to be higher among older adults who are:

- Low income

- Less educated (i.e., less than a high school education)

- Racial minorities (i.e. non-Caucasian individuals)

- Separated or divorced, or never married

- Unemployed

- Living with a disability

- Living alone

- Environmental Barriers

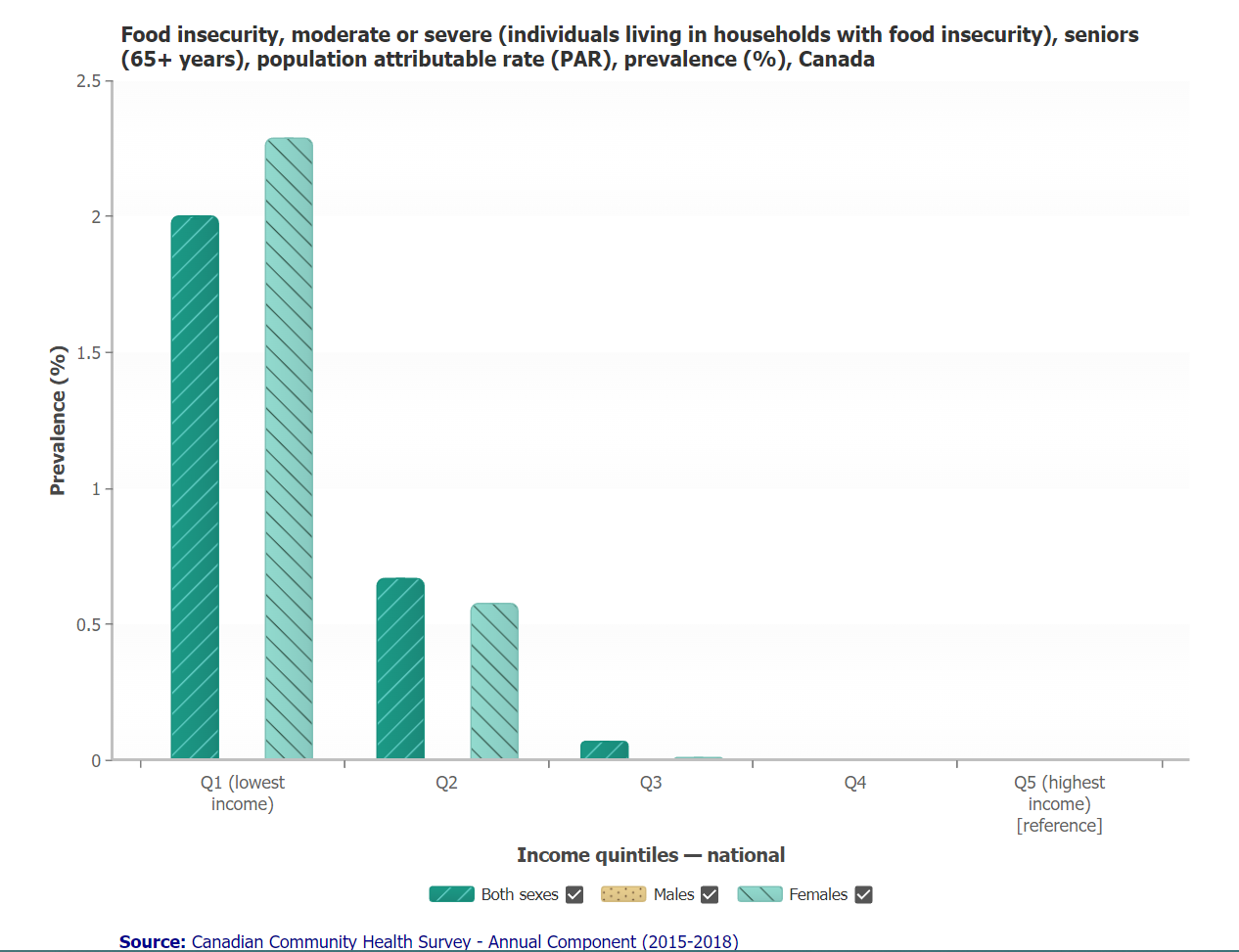

Among older adults aged 65+ in Canada, the moderate or severe food insecurity rate is highest for those in the lowest income quintile (Government of Canada, 2023). As income levels increase, rates of food insecurity fall. This can be observed when looking at Figure 10.1.1 with combined data obtained from the 2015-2018 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS).

Figure 10.1.1. The prevalence of food insecurity (moderate or severe) among seniors (65+ years), contrasted with national income quintiles.

In addition to the ability to purchase food, economic status and social support can impact nutrition status in other ways. The ability to remain at home and prepare meals may be affected by available social networks, income level, or disability. People experiencing food insecurity often consume a nutrient-poor diet, which may contribute to the development of obesity, heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and other chronic diseases that require a special diet to help manage, further exacerbating health.

10.2 Health Factors

Canada’s Ministry of Health includes the following overview in their guide “Healthy Eating for Seniors” (Canada, 2022). Some older adults experience life changes and health changes that can make it more challenging to eat well.

Within personal frameworks, such changes may include physical changes that:

- Impact appetite

- Alter sense of taste or smell

- Impact digestion, ability to chew or swallow

- Make it more difficult to get to the grocery store

- Make it more difficult to spend a lot of time preparing food

- Impact your ability to shop for or cook food or do tasks like open jars

The impacts of these physiological changes vary. Making a nutrition plan is warranted when issues impact food intake and nutritional quality.

10.3 Psychosocial Knowledge/Skills & Preferences

Relationships in Late Adulthood

Many people find that their relationships with their adult children, siblings, spouses, or life partners change during late adulthood. Roles may also change, as many are grandparents or great-grandparents, caregivers to even older parents or spouses, or receivers of care in a nursing home or other care facility.

Friendships

Friendships influence life satisfaction during late adulthood. Friends may be more influential than family members for many older adults. Friendships are not formed to enhance status or careers and may be based purely on a sense of connection or the enjoyment of being together. Most older adults have at least one close friend. These friends may provide emotional as well as physical support. Talking with friends and relying on others is very important during this stage of life (Carstensen, Fung & Charles, 2003).

Grand-parenting

Grandparenting typically begins in midlife rather than late adulthood, but because people live longer, they can anticipate being grandparents for longer. It has become increasingly common for grandparents to live with and raise their grandchildren or to move back in with adult children in their later years (Carstensen, Fung & Charles, 2003).

Marriage and Divorce

Most males and females aged 65 and older had been married at some point. Twelve percent of older men and 15% percent of older women have been divorced, and about 6 percent of older adults have never married (Roberts & Stella, 2016). Many married couples feel their marriage has improved with time, and the emotional intensity and level of conflict that might have been experienced earlier has declined. This is not to say that bad marriages become good over the years, but that those very conflict-ridden marriages may no longer be together, and many of the disagreements couples might have had earlier in their marriages may no longer be an issue. Children have grown, and the division of labour in the home has more likely been established. Men tend to report being satisfied with marriage more than women. Women are more likely to complain about caring for an ill spouse, accommodating a retired husband, and planning activities (Cassell, 2007).

Figure 10.3.1. Both divorce and remarriage are on the rise for older Americans.

Divorce after long-term marriage does occur, but it is not as common as earlier divorces, despite rising divorce rates for those above age 65. Older adults who have been divorced since midlife tend to have settled into comfortable lives and, if they have raised children, to be proud of their accomplishments as single parents.

Widowhood

With increasing age, women are less likely to be married or divorced but more likely to be widowed, reflecting a longer life expectancy than men (Cohn, 2011). A spouse’s death is one of life’s most disruptive experiences. It is especially hard on men who lose their wives. Often widowers do not have a network of friends or family members to fall back on and may have difficulty expressing their emotions to process grief. Also, they may have depended on their mates for routine tasks such as cooking, cleaning, etc.

Widows may have less difficulty because they usually have a social network and can take care of their daily needs. They may have more difficulty financially if their husbands handled all the finances in the past. They are much less likely to remarry because many do not wish to and because fewer men are available (Cohn, 2011).

10.4 Social Isolation and Loneliness

Social isolation and loneliness are separate but related concepts that negatively impact the health and well-being of older adults. Social isolation generally refers to the objective absence of meaningful and sustained connections with others, whereas loneliness usually refers to a perceived lack of connection. Studies have found that higher levels of social isolation and certain life events are associated with higher odds of loneliness. Social support, including from friends, can alleviate loneliness, which can serve as an important pathway for well-being and can provide meaningful connections. Promoting social participation and decreasing isolation through meaningful participation in community building are important strategies to promote health equity among older adults and reduce the risk of poor health.

Older adults who experience social isolation and extended periods of loneliness are at higher risk for poorer physical and mental health. As eating is very social and eating regular meals can be found to depend on eating with others. Therefore, loneliness due to losing a spouse or friend can diminish the social reasons for and pleasure associated with eating. Impacts caused by this include lower overall intakes due to low motivation to cook for oneself, physical or mobility issues that impact one’s ability to cook, and lack of knowledge of changing nutrient needs, all of which can lead to adverse health outcomes.

Older Adults and LBGTQ+

LGBTQ+ older adults often have unique experiences and needs that create additional social support and loneliness considerations. Many LGBTQ+ older adults came of age during a time of significant victimization and discrimination toward LGBTQ+ people, which may make them more vulnerable to social isolation or loneliness as they age. It has been reported that LGBTQ+ older adults have high rates of mental distress, chronic disease, and disability. LGBTQ+ older adults are twice as likely to live alone and four times less likely to have children as their non-LGBTQ+ peers, putting this population at a higher risk of loneliness and social isolation (Perone, Ingersoll-Dayton, & Watkins-Dukhie, 2020). Given decades of structural discrimination in family creation and rejection from biological families, many LGBTQ+ older adults have created social networks based on families of choice (non-biological friends, partners, ex-partners, neighbours, and co-workers) that act as surrogate families. While families of choice offer important social support, they can present challenges because they are often comprised of peers the same age. As families of choice age together, social networks and connections can dwindle as health issues arise that preclude providing support and care to one another. While transgender older adults have identified larger and more diverse social networks, they have also reported limited social support. A heightened level of distrust towards healthcare and social service professionals, given repeated experiences of discrimination, may also produce more social isolation among transgender older adults (Perone, Ingersoll-Dayton, & Watkins-Dukhie,2020).

Leading & Learning with Pride: A Revitalized Tool Kit on Supporting 2SLGTQI+ Seniors.

For further in-depth information on social variables impacting the LGBTQ community, please read the following resource: https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/8ef3-Leading-Learning-WITH-PRIDE-A-Revitalized-Tool-Kit-on-Supporting-2SLGBTQI-Seniors.pdf

This resource is an outline for creating lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender culturally competent care in Canada long-term care homes and services.

This chapter has been adapted from ‘Lifespan Development’ by Lumen Learning: https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/lumenlife/

Creative Commons Attribution: BY

References

Canada, H. (2022, May 3). Healthy eating for seniors. Canada Food Guide. https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/tips-for-healthy-eating/seniors/

Carstensen, L. L., Fung, H. H., & Charles, S. T. (2003). Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and emotion, 27, 103-123.

Cassell, Heather (18 October 2007). “LGBT Health Care Movement Gains Momentum”. Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

Cohn, D. V. (2011). Census Bureau Releases 2010 American Community Survey Data.

Government of Canada (2023). Health inequalities data tool. Health Inequalities Data Tool (canada.ca)

Gross, Jane (October 9, 2007). “Aging and Gay, and Facing Prejudice in Twilight”. The New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

Higgs, S., & Thomas, J. (2016). Social influences on eating. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 9, 1–6. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S235215461500131X?via%3Dihub

Livingston, Gretchen (2014). Chapter 2: The Demographics of Remarriage. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/11/14/chapter-2-the-demographics-of-remarriage/.

National Poll on Healthy Aging/University of Michigan. (2019, March). Loneliness and Health. Retrieved from https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/148147/NPHA_Loneliness-Report_FINAL-030419.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

Passel, J. and Cohn, D. (n.d.). A record 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/05/a-record-64-million-americans-live-in-multigenerational-households/.

Perone, A., Ingersoll-Dayton, B., & Watkins-Dukhie, K. (2020). Social isolation loneliness among LGBT older adults: Lessons learned from a pilot friendly caller program. Clinical Social Work Journal, 48(1), 126-139.

Roberts, A. & Stella, O. (2016). The Population 65 Years and Older in the United States: 2016 American Community Survey Reports. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/acs/ACS-38.pdf.

Media Attributions

- Screen Shot 2022-11-06 at 2.42.09 PM

- Screen Shot 2022-12-21 at 12.04.45 PM