2 Personal Privilege and Bias

Learning Objectives

- Articulate an expanded awareness of concepts and theoretical frameworks surrounding identity, power, and privilege, including intersectionality, bias, and microaggressions.

- Reflect on how your own identities and experiences intersect with other identities, power, and privilege.

- Connect how identity, power, and privilege relate to your role as an educator.

Introduction Video

|

Throughout the module, we use this icon to suggest times to reflect on a concept, your professional practice, or yourself. We hope these questions help spark your thinking in new and creative directions. |

Reflecting on Identity

Reflecting on our identities and acknowledging how they manifest in our education practice is ongoing work. Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your own identities and how they relate to this module.

Consider your own personal learning about the topic. Where do you fall on the following continuum?

| I have not yet begun thinking about this |

I have started to learn more about this. |

I am actively thinking and learning about this. |

I am applying my new learningand remain committed to further reflection and growth. |

|---|---|---|---|

- In what ways does my social and geographical location influence my identity, knowledge, and accumulated wisdom? What knowledge am I missing?

- What privileges and power do I hold? In what ways do I exercise my power and privilege?

- Does my power and privilege show up in my work? If so, how?

- Am I aware of if/how my biases and privileges might take up space and silence others?

It’s important to realize that you do not have to be an expert on these topics to actively engage in self-reflection and conversations with students. Being an equity-centred educator requires regular and repeated reflection on the Eurocentric assumptions, knowledges, and ways of being that guide our thoughts and actions.

Being aware of which knowledges, experiences, and ways of being in the world are privileged in your discipline, classroom, and institution are a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is legitimate action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Anti-oppressive education and critical pedagogy

[Critical pedagogy is] Habits of thought, reading, writing, and speaking which go beneath surface meaning, first impressions, dominant myths, official pronouncements, traditional clichés, received wisdom, and mere opinions, to understand the deep meaning, root causes, social context, ideology, and personal consequences of any action, event, object, process, organization, experience, text, subject matter, policy, mass media, or discourse.

– Ira Shor[1]

Brazilian educator and educational philosopher Paulo Freire developed the school of thought known as critical pedagogy. He believed that education was a revolutionary act capable of and responsible for bringing about a better and more equitable society.

Any society, institution, or system can be oppressive. This includes education systems and institutions. In Module 1, Systems of Inequity, we learned about systems of power and oppression, including white supremacy and white privilege. These systems create barriers in the form of policies, procedures, and practices that prevent individuals from having equitable access to education.

…[C]ulture refers to a dynamic system of social values, cognitive codes, behavioral standards, worldviews, and beliefs used to give order and meaning into our own lives as well as the lives of others[2]… Because teaching and learning are always mediated or shaped by cultural influence, they can never be culturally neutral[3]

– Geneva Gay[4]

Some examples of ways that education practices and spaces can be oppressive include:

- Institutional leadership that lacks diversity

- Eurocentric course content that does not represent the ways of knowing, experiences, and stories of Indigenous people, African Canadians, and people of colour

- Physical spaces where accessibility is an add-on or afterthought, not a given. For example, having to ask a staff person for an elevator key to access upper floors in a building

- Forms that only include “female” and “male” as gender options

Critical pedagogy is based on the idea that social justice and democracy are not separate from teaching, learning, and student support. The goal of critical pedagogy is to free our students and ourselves from oppression by growing an in-depth understanding of our world and how its social and political structures affect us, our students, and our professional practice.

In this context, it is the educator’s responsibility to help lead students to question oppressive beliefs and practices, including those at school, and encourage responses and actions that collectively and individually liberate them from the oppressive conditions of their lives.

There is no such thing as neutral education. Education either functions as an instrument… [to] bring about conformity… or… freedom.

– Richard Shaull[5]

In other words, one of your most important tasks is to create an environment and educational practice that is safer and more inclusive and invites your students to ask questions, respectfully challenge authority, and work to change their — and our — world for the better.

Thinking about difference

The students you encounter each day bring their lived experiences and identities with them.

All students identify with multiple identities and experiences. They may, for example:

- identify as racialized, Indigenous, immigrant, 2SLGBTQ+, or as people with disabilities or who experience barriers to accessibility, such as those who identify as Deaf or neurodivergent[6]

- have experienced poverty or the child welfare system

- be the first in their family to pursue post-secondary education, or come from a rural area and not have experience living in a city

As professionals, part of our role is to understand and acknowledge how these identities and experiences show up in the classroom and student services environment. Critical pedagogy helps us understand and accept this diversity and work to create an inclusive educational experience.

What I Wish My Professor Knew

To help you think more about your students’ lived experiences, watch What I Wish My Professor Knew (7:24) a video created by Stanford University’s student-run First-Generation and/or Low-Income Partnership (FLIP). This video is created to help Stanford faculty understand how their classroom practices and statements could make the difference between first-generation and/or low-income students feeling alienated or welcomed at university.[7]

|

Reflect |

- What do you think students at your institution would want you to know about their lives and what they need?

- What statements from the video resonated with you or surprised you? Why?

- How might the students’ perspectives on their learning experiences impact your own pedagogy and/or practice?

Unpacking Language: Key Terms

Words matter, and words can have multiple meanings

In this section, you’ll engage with several important words and ideas related to power, privilege, and bias. We will only skim the surface of these important, complex, and deep-seated issues.

The purpose of this section is to establish a shared understanding and vocabulary to build on in future modules. This work is essential but is also sometimes uncomfortable. This should not deter us from doing it.

As a staff or faculty member, recognizing and addressing the meanings of these words in your planning and reflection is important. The more clearly a term is articulated, the more likely you are to develop the knowledge and skills to use it. You will also feel more comfortable talking about and using these words in your teaching and interaction with students.

Write

Take a couple of minutes to jot down your understanding of the following key terms (don’t worry about getting it right or perfect; the idea is to respond quickly):

- power

- privilege

- oppression

- inclusion

- diversity

- equity

- white supremacy

Review

Now, review the following definitions to see how your understanding of key terms aligns:

power: Control, authority, or influence over other people or events; the right to do something or act in a particular way.

privilege: A special advantage, right, or prerogative possessed by an individual or group. Privilege is often gained by birth or social position but can also be acquired through effort and accomplishment.

oppression: Cruel or unjust treatment or control, usually over a prolonged period of time. Oppression describes the feeling and experience of being heavily burdened, mentally or physically, by troubles, anxiety, and adverse conditions.[8]

inclusion: Inclusion can refer to the policy or practice of providing equal access to opportunities and resources to people who might otherwise be excluded or marginalized.[9] Inclusion also requires us to challenge and dismantle systems of oppression, racism, and inequity to make a new and better space for everyone.

diversity: Variety. Diversity often refers to including or involving people from a range of different backgrounds, including gender, culture, racialized identity, sexual orientation, ability, socioeconomic status, etc.[10]

equity: Fairness and impartiality. Equity is different from equality. Equality means everyone gets the same thing (treatment, resources, support, etc.); equity recognizes that people may need different things to ensure their opportunities are the same as others.

white supremacy: The belief that people who see themselves as white are superior to Black, Indigenous, and people of colour and should therefore dominate them. White supremacy perpetuates and maintains social, political, historical, and institutional domination by white people. For example, white supremacy justified the transatlantic slave trade and colonization around the world. Today, it is used to justify entrenched systemic, structural, and institutional racism.[11] White supremacy also refers to the political and socio-economic systems that give white people structural advantages over racialized people — both collectively and individually.

|

Reflect |

- Which terms did you feel most confident defining? Which ones felt more difficult? Why do you think this is?

- How has your understanding of these terms changed over time?

Situating Ourselves

Situating our identities

Tereigh Ewert: Locating your own social identities and bringing them into the classroom

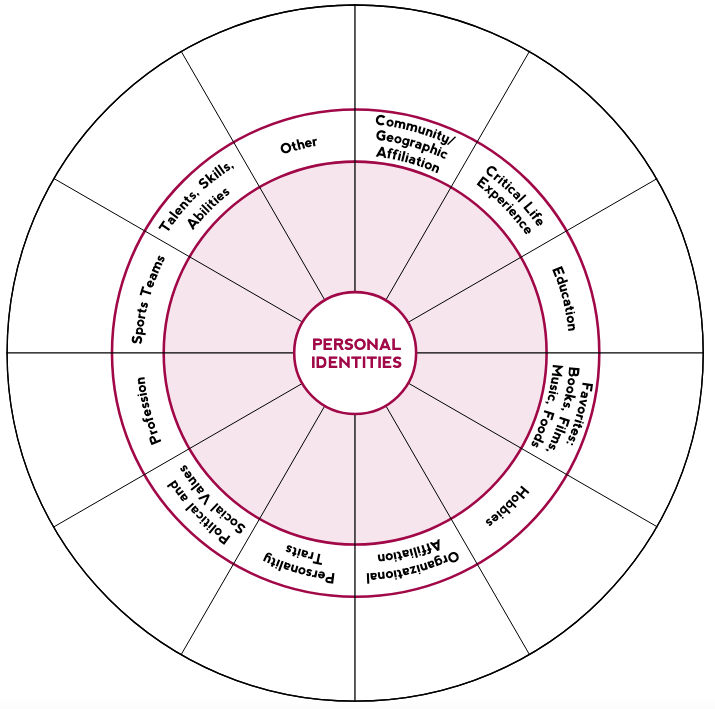

The Personal Identity Wheel Activity

Download and print the Personal and Social Identity Wheel by the American Association of University Women (adapted from Arizona State University) for its Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit.

The Personal Identity Wheel encourages us to reflect on how we identify specifically outside of social identifiers.

Fill out the worksheet by listing adjectives you would use to describe yourself, the skills you have, your favourite books and hobbies, and more.

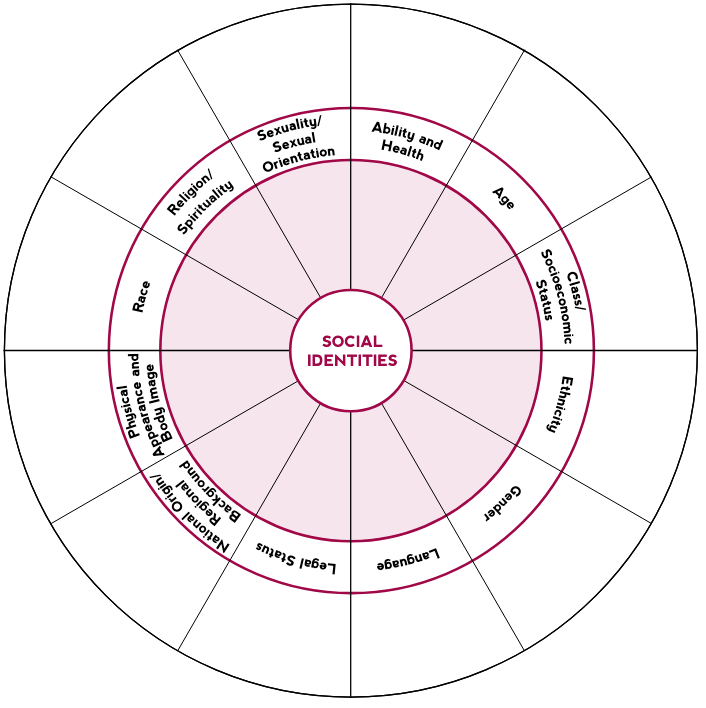

The Social Identity Wheel Activity

The Personal and Social Identity Wheel encourages us to reflect on the ways we identify socially, how those identities become visible or more keenly felt at different times, and how they affect the ways others perceive or treat us.

Fill out the worksheet by listing your social identities (e.g., religion, racialized identity, gender, sex, ability or ability, sexual orientation and so on) and further categorize those identities based on which matter most in your self-perception and which matter most in others’ perception of you.

Using the Social and the Personal Identity Wheels encourages us to reflect on the relationships and dissonances between our personal and social identities.

|

Reflect |

Consider the following as you reflect on the identity wheels you just completed.

Which of your identities…

- Do you think of most often?

- Are less apparent or even invisible in your day-to-day life?

- Are most critical to your personal sense of yourself?

- Most affect how others perceive you (positively or negatively)?

- Have the most effect on how you perceive others?

- Face the most marginalization — or give you the most advantage — in your community?

You may now be seeing that some aspects of our identities can’t be hidden, and some can’t be changed. This is especially important when considering which aspects of our identities are more valued in our communities and which aspects are more socially marginalized.

As people with many social identities, we may sometimes find ourselves members of dominant, more powerful groups, and sometimes members of groups that are more marginalized. These experiences of dominance and marginalization can also occur simultaneously.

Intersectionality

There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.

– Audre Lorde, 1984[12]

Nik Basset: Intersecting identities, liberation, and justice

Our identities are multiple and overlapping

You may have noticed in the previous section that our identities are not singular. Our identities are multiple and overlapping. They INTERSECT. This intersectionality can fundamentally alter how we experience social challenges and how we grasp our individual realities. All of this comes into play when we interact with, teach, and support students.

Intersectionality: Elements of our identities that might intersect include, but are not limited to:

- Socioeconomic class

- Nationality

- Sexuality

- Geography

- Racialized identity/ethnicity

- Indigeneity

- Gender, gender identity, and gender expression

- Age

- Ability

- Immigration status

- Religion

These interactions happen within interconnected systems and structures of power. Laws, policies, governments, schools, institutions, people, and organizations with social and economic power interact to create interdependent forms of privilege and oppression.

For example, your experiences as an Indigenous woman are informed by intersections of Indigeneity and gender. Your experiences as an African Nova Scotian who uses a wheelchair are informed by intersections of race and ability.

Intersectionality helps us take action on our professional practice to create equitable educational, social, and economic opportunities for our students. It lets us see each other for who we are and how we came to be here.

Understanding Intersectionality

Understanding intersectionality is essential to understanding our students and each other. It is a distinct and crucial component of thoughtfully considering and supporting equity in the classroom and in student services.

Intersectionality lets us see each other as shaped by the interaction of our multiple identities, including but not limited to racialized identity/ethnicity, Indigeneity, gender, gender identity, class, sexuality, geography, age, ability, migration status, and religion.

These interactions happen within interconnected systems and structures of power: Laws, policies, education, governments, institutions, and people and organizations with social and economic power interact to create interdependent forms of privilege and oppression.

What is Intersectionality About?

Intersectionality is not simply about adding up or listing identities. It’s about how the world we live in — its policies, its institutions, its structures — has different impacts on us, in part depending on our identities.

Kimberlé Crenshaw is an African American lawyer, civil rights advocate, philosopher, and a leading scholar of critical race theory who developed the theory of intersectionality. In the keynote address on intersectionality delivered at the 2016 World of Women (WOW) Festival, she explains:

“[Intersectionality] is about how structures make certain identities the consequence of and the vehicle for vulnerability. So, if you want to know how many intersections matter, you’ve got to look at the context. What’s happening? What kind of discrimination is going on? What are the policies? What are the institutional structures that play a role in contributing to the exclusion of some people and not others?”[13]

Complexity of identity

Learn more about the complexity of identity in this article by Pamela E. Barnett: Unpacking Teachers’ Invisible Knapsacks: Social Identity and Privilege in Higher Education. The article highlights how some aspects of identity, such as gender and age, carry both specific social privileges and liabilities that come into play in higher education.[14]

|

Reflect |

Intersections of identity in your own life

Consider the intersections of identity in your own life

- Which, if any, of your personal and social identities give you advantages or privileges in life, at school, at work, or in your community?

- Which, if any, of your personal or social identities give you privilege in some contexts but come up against barriers in others?

- In what ways do your own social identity groups intersect?

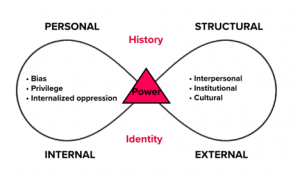

Framework for Understanding Privilege and Identity

Privilege and identity are complicated, and they interact in complex ways.

New Forms of Transformative Education: Pedagogy for the Privileged, by Dr. Ann Curry-Stevens at University of British Columbia (UBC), includes a sample framework to understand and create greater awareness about our own identities and how they position us in relation to others and to our work. The article identifies actionable steps to build a transformative tool kit to engage privileged learners and support their transformation into allies in the struggle for social justice.

|

Reflect |

Curry-Stevens’ 10 Steps[15]

- Awareness of oppression

- Oppression as structural and thus enduring and pervasive

- Locating oneself as oppressed

- Locating oneself as privileged

- Understanding the benefits that flow from privilege

- Understanding oneself as implicated in the oppression of others and understanding oneself as an oppressor

- Building confidence to take action – knowing how to intervene

- Planning actions for departure

- Finding supportive connections to sustain commitments

- Declaring intentions for future action

Consider the 10 stages identified in the framework

- At which stage are you in this confidence shaking/confidence building framework?

- Why do you think you’re at that stage?

- Where would you like to be and how would you like to get there?

- How do you see yourself working with colleagues to support each other in becoming better allies for students with identities that have been marginalized?

Implicit Bias

Implicit bias, also sometimes called unconscious bias, refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that unconsciously affect our understanding, actions, and decisions.[16] These biases include assumptions about other people that affect:

- our expectations of them

- our assessment of their work or behaviour

- our judgments about their characteristics as individuals or as a group

Everyone has implicit biases. It can be very difficult to see our own implicit biases, or even admit that we have them. We form them throughout our lives as we are exposed to direct and indirect messages from our families, communities, and the media.

Not everyone has the same implicit biases, and it is possible to change our implicit biases over time by intentionally practicing more mindful decision-making; thinking carefully about our own attitudes and reactions; and participating in training like this. Implicit biases can also be challenged and changed through more accurate and inclusive representation of underrepresented or marginalized groups in the media, in public institutions, and in positions of power and influence.

Aboriginal Issues In The Classroom

What I Learned in Class Today: Aboriginal Issues in the Classroom (20:41) a video about everyday biases experienced by Indigenous people in educational settings.

A few key characteristics of implicit bias[17]

- Implicit biases are attitudes or stereotypes that affect our perceptions, impressions, and actions

- Implicit biases are pervasive — this means they are widespread, persistent, and inescapable. They are often the result of dominant norms and structures in society that lead us to understand the world and other people in particular ways. Everyone holds implicit biases, even people obligated to impartiality, like judges

- Implicit and explicit biases are related but distinct. They are not mutually exclusive and may even reinforce each other.

- Our implicit biases do not necessarily align with our declared public beliefs. We might hold an unconscious bias even when our intention is to be inclusive and promote equity. Implicit biases can be positive (a preference for something or someone) or negative (an aversion to or fear of something or someone).

- We tend to hold implicit biases that favour our own in-group, though research has shown that we can also hold implicit biases against our in-group.

Our stories matter. Our personal and professional lives are made up of many overlapping stories — not a single story.

Implicit biases are involuntary

They affect us without our awareness, often because of single stories we’ve heard about certain people or places, or because of stereotypes or assumptions we’ve inherited from our backgrounds or upbringing.

Author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie uses the idea of the single story to describe the simplistic and often false perceptions we form about individuals, groups, or countries. This single story creates and maintains stereotypes. Adichie says the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. To learn more, listen to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED Talk (18:33).

Actions or reactions driven by implicit biases don’t take into account the many parts of identity that interact and intersect within a single individual.

How can we actively and intentionally listen and learn — and unlearn — the stereotypes we have internalized, and add multiple stories to the single story we might hold about an individual or group?

Through reflection, it’s possible to question even implicit biases and bring richer, multiple voices and stories to your professional practice and everyday life.

What does my headscarf mean to you?

What does my headscarf mean to you? (13:53). Watch the TEDxSouthBank talk by Yassmin Abdel-Magied. She challenges us to look beyond our initial perceptions and to open doors to new ways of supporting others.

|

Reflect |

On Implicit Bias

- Where did your implicit bias come up during the video?

- What happened or was said in the video to trigger it?

- Where do you think this bias came from?

More About Implicit Bias

Implicit bias is a complex concept used in different ways in different fields. It is also subject to many critiques. Implicit biases can be changed and challenged. You can form strategies to help you cultivate new ways of approaching your own biases.

To go deeper and learn more about some of these critiques, read The world is relying on a flawed psychological test to fight racism, by Oliva Goldhill posted December 3, 2017 on Quartz.

Deepen Your Understanding of Implicit Bias

To deepen your understanding of bias, we invite you to either read an article or listen to a podcast and appreciate the complex stories of people’s lived experiences.

Read

I fight anti-Black, anti-Indigenous racism with academic excellence, by Jordan Gray posted Ocotber 13, 2020 on CBC news Ottawa. Jordan Gray, an award-winning researcher, talks about his experiences as a student.

Watch

How racial bias works – and how to disrupt it a Ted2020 Talk by Jennifer L. Eberhardt.

|

Reflect |

Take a moment to reflect on how single stories operate and how stories matter by considering these questions:

- What’s an example of how a “single story” operates in your personal life?

- What’s an example of how a “single story” operates or has operated in your professional practice?

- What strategies will you use to challenge single stories in your professional practice?

Consider the following areas:

- your syllabus and course resources

- student engagement

- forms of assessment

- classroom arrangement and course policies

- images or examples used when lecturing or explaining concepts

- the physical spaces where students meet with you

- how you counsel and support students: techniques, tools, and approach the group activities you lead

Activity

Researchers at Harvard University have developed over a dozen tests for measuring implicit bias related to racialized identity, sexuality, ability, religion, and other forms of prejudice as part of Project Implicit. Visit the Project Implicit site and take the Race IAT. (You may also choose to take other tests).[18]

After you view your results, reflect on the test itself, your experience taking the test, and your interpretation of the results. Consider how colonization impacts all of us.

NOTE: Project Implicit has faced intense scrutiny and not everyone agrees that it is useful or safe. If you choose to take the test, you may feel upset or surprised by the results. It’s a good idea to plan a debrief with a trusted friend or colleague.

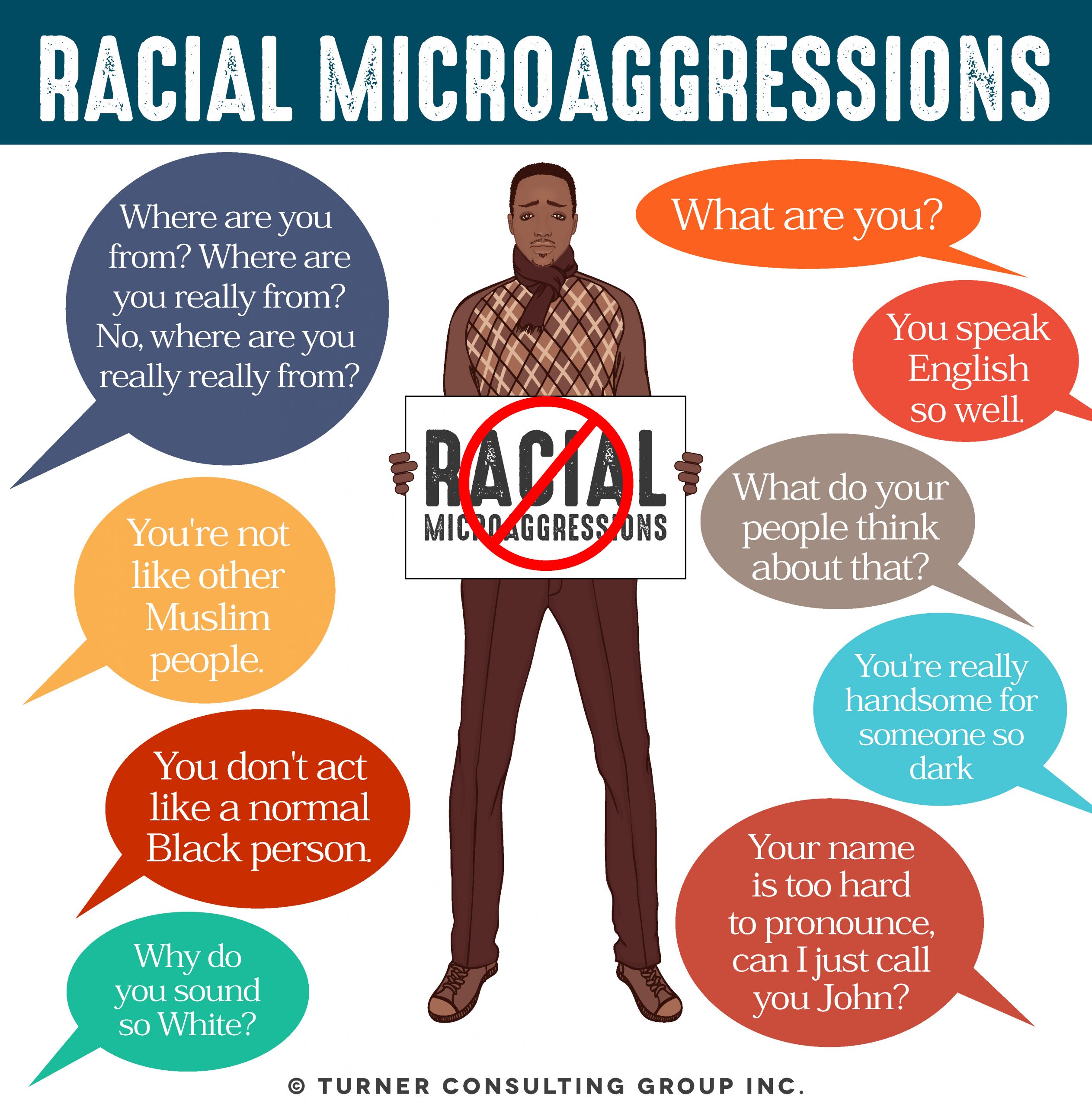

Microaggressions have a big impact

Microaggressions target people or groups through hostile, derogatory, or negative messages based on their group membership. These subtle everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental insults, slights, snubs, or demeaning messages can be based on any aspect of a person’s identity who has been marginalized: socio-economic status, ability, sex, gender, gender expression or identity, sexual orientation, racialized identity, ethnicity, nationality, or religion.

Microaggressions are often part of a pattern of behaviour, and the cumulative effects of these small attacks can be devastating. However, microaggression is a contested term.

I do not use “microaggression” anymore. I detest the post-racial platform that supported its sudden popularity. I detest its component parts—“micro” and “aggression.” A persistent daily low hum of racist abuse is not minor. I use the term “abuse” because aggression is not as exacting a term. Abuse accurately describes the action and its effects on people: distress, anger, worry, depression, anxiety, pain, fatigue, and suicide.

― Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist[19]

Perpetrators of these subtle forms of abuse are often unaware of the impact of their words or actions and may feel defensive about them. They may even consider themselves to have good intentions.

Stories by African Nova Scotians

Stories by African Nova Scotians about personal experiences of microaggressions on the Working While Black website. Working While Black is a project that publishes anonymous stories of anti-Black racism in the workplace in Nova Scotia.

Anyone in a school community — faculty, students, or staff — can be a perpetrator OR a target of microaggressions. There are many different kinds of microaggressions.

Nik Basset: Microaggressions and queering the curriculum (3:02)

Common Microaggressions

Microaggressions Behaviours and Actions

Microaggressions also include the following behaviours and actions:

- Expressing personal or political opinions assuming that the targets of those opinions are not present

- Singling students out in class because of their backgrounds, or expecting students of a particular group to represent the perspectives of others who share their identity

- Denying the experiences of students by questioning the credibility and validity of their stories

- Assigning projects or creating school procedures that are heterosexist, sexist, racist, or promote other oppressions, even inadvertently

- Using sexist language

- Using heteronormative metaphors or examples in class

- Assuming the gender of any student

- Continuing to misuse pronouns even after a student, transgender or not, indicates their preferred gender pronoun

You might be wondering what the big deal is about an unintentional microaggression.

An individual microaggression may not be deeply damaging to the person experiencing it, but microaggressions have a devastating cumulative effect on people’s social, emotional, and even physical well-being over time.

Activity Microaggressions:

Choose one post from the blog Microaggressions: Power, Privilege, and Everyday Life.

- Write down the role that both a single-story approach and intersecting identities played in creating the situation the writer is describing

- Think about what it would feel like to experience microaggressions on a regular basis: monthly, weekly, even daily. What effect would it have on you? How would you cope?

Consider sharing this activity with a colleague and discussing your thoughts about two or three different posts.

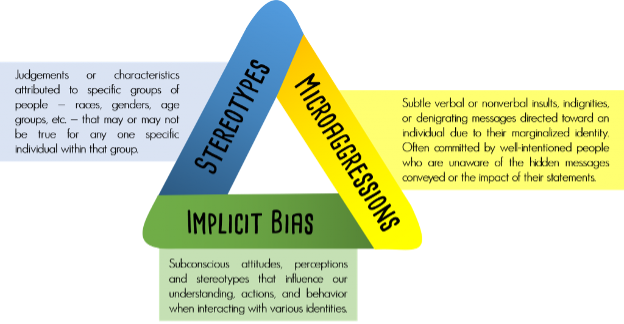

The relationship between implicit bias, microaggressions, and stereotypes

It’s probably becoming clear to you that implicit bias, microaggressions, and stereotypes are closely related. Exposure to stereotypes and other misinformation over time leads to implicit biases, which can then lead us to commit microaggressions against people with identities that have been marginalized.

The following diagram from Project READY shows how these three concepts interact.

|

Reflect |

Consider the role of microaggressions in your own life

- Describe any microaggressions you’ve experienced at work or at school. What effect did they have on you? On how you were treated by others?

- If you have not experienced microaggressions, why do you think that is?

- Can you think of any examples of times you witnessed or committed a microaggression without realizing it? What could have happened differently?

Power and Privilege in Educational Institutions

This module on power, privilege, and bias has introduced some important and challenging concepts and terms. The following modules will build on what you’ve learned and reflected on here. We encourage you to keep listening, reading, learning, and thinking about how our identities influence our interactions with others in complex and layered ways.

We all choose whether or not to share parts of our identity with different people, depending on our circumstances and how safe we feel; parts of our identity may remain hidden in our day-to-day lives, and the same is true for our students’ identities. This impacts our approach to teaching and supporting students. How we deal with identities is also central to whether or not students can succeed in our educational institutions.

Jean-Blaise Samou: The foundations of the education system and psychological segregation of people of colour.

|

Reflect |

Identities, Power, and Privileges in Educational Institutions

Think about the different situations where you interact with students. This could be courses you teach, programs you lead, or supports you provide.

- Which identities do you present to students (especially when you first meet them)?

- Are these identities generally visible or do you make them visible?

- Are these identities socially valued or more marginalized?

Now think about your students

- Are certain identities and voices made more visible/invisible in your space or classroom?

- What are you communicating about the value of certain identities in your space or classroom?

- What examples do you see of oppression or exclusion in your daily work? What about equity and inclusion?

Let’s connect these questions to the concepts you’ve engaged with so far:

- How would you describe the connection between identity, power, and privilege? How do your identities reflect your power and privilege? Or not?

- In light of your answers, how have you navigated your own power and/or privilege in your professional practice?

- What changes might you make going forward?

Reflecting on Systems

Now that you have completed this module, we invite you to continue your learning by exploring the themes of decolonization, thinking more concretely about inclusive practices, learning about Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and/or considering courageous conversations in your interactions with students.

Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your institution as a system and how it relates to this module. Think about the written and unwritten rules, policies, procedures, practices, and traditions that define your institution.

|

Reflect |

Reflect on and write a few lines answering these questions:

- Who is welcomed and can fully participate?

- Who may be excluded, discriminated against, or denied full participation?

- Whose norms, values, and perspectives does the institution consider to be normal or legitimate? Whose does it silence, marginalize, or delegitimize?

- Who inhabits positions of power within the institution?

- Whose experiences, norms, values, and perspectives influence an institution’s laws, policies, and systems of evaluation?

- Whose interests does the institution protect?

Systems of Inequity

Thank you for taking the time to reflect on your own institution in relation to this module. Being aware of the policies, procedures, practices, and traditions and how they intentionally or unintentionally privilege some groups over others is a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is real action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Conclusion

Summary

This module built a foundation for your learning about social equity and introduced you to some complex ideas about identity, power, and privilege — and how those ideas intersect with your role and responsibility as an educator or student services professional.

This module unpacked implicit biases, stereotypes, and microaggressions, and how they come together to affect equity in education. As you learn, it’s important to further reflect on where you can find opportunities to disrupt oppressive practices.

Learn More

Watch

This CBC town hall about racism in Nova Scotia was recorded in 2018. This recording is long but it contains a great deal of local context that is critical to developing a deeper understanding of racism in Nova Scotia, particularly Halifax. Facing Race Halifax (2:35:13)

Implicit Bias, Lifelong Impact by the Kirwan Institute (5:40)

Do

The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity has partnered with MTV to create a series of three seven-day bias cleanses (3:15) designed to help individuals identify and begin dismantling some of their own associations related to racialized identity, gender, and sexuality. Over the course of one week, complete the race bias cleanse. After you enter your email, you will receive a series of seven daily emails from the project, each containing a brief exercise, tool, or thought starter.

The blog post, 7 Easy Activities That Encourage Students to Open Up About Identity and Privilege by Jodi Tandet posted April 16, 2019 to Presence, lists activities you can do as a student services/affairs professional to get students talking about identities.

Listen

After a 2018 incident in Philadelphia where two Black men were arrested at Starbucks, the coffee company decided to close all 8,000 of its stores for an afternoon to provide implicit bias training for its staff. Listen to the NPR All Things Considered segment, in which Perception Institute director Alexis McGill Johnson explains how racial biases might be lessened over time with intentional effort.[20]

Read

Understand more about the origins of critical pedagogy by visiting the Freire Institute website. This organization develops tools and approaches based on the work of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, whose work has inspired many social movements and educational programmes around the world.[21]

On being an ally and being called out on your privilege by Andrew David Thaler posted November 19, 2013 to Southern Fried Science.

Attribution

The sections listed below were adapted from University of British Columbia and Queen’s University. (n.d.). Inclusive Teaching: Module 1: Power, Privilege and Bias. [online curriculum]. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license:

- Learning Objectives from 1. Introduction to Power, Privilege and Bias – Learning Outcomes

- Unpacking Language: Key Terms paragraphs from 2. Unpacking Language

- The Personal Identity Wheel Activity, The Social Identity Wheel Activity, and Explore the complexity of identities text from 3.2 Activity: Personal and Social Identity Wheels

- Intersectionality paragraphs adapted from 3.3. Intersectionality.

- Framework for Understanding Privilege and Identity paragraphs and steps adapted from 3.4 Framework for Understanding Privilege and Identity.

- Shor, I. (1992). Empowering Education: Critical Teaching for Social Change. University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Delgado-Gaitan & Trueba 1991 ↵

- Ginsberg, 2015; Kuykendall, 2004; Ortiz, 2013 ↵

- Gay, G. (2010). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice (p.8). Teachers College Press. ↵

- Shaull, R. (1970). Foreword to Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed. (p.34). The Continuum International Publishing Group: New York. ↵

- Council of Nova Scotia University Presidents & Nova Scotia Community College. (2020). Nova Scotia Post-Secondary Accessibility Framework (p. 3.). https://www.nscc.ca/docs/about-nscc/nova-scotia-post-secondary-accessibility-framework.pdf ↵

- Adapted from University of British Columbia & Queen's University. (n.d.). 1.2 Critical Pedagogy. In Inclusive Teaching: Power, Privilege and Bias. [online curriculum]. https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/31444/pages/1-dot-2-critical-pedagogy?module_item_id=1553108 ↵

- Adapted from Dictionary.com, LLC (2021). Oppression. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/oppression ↵

- Lexico.com. (2021). Inclusion. Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/inclusion ↵

- Adapted from Lexico.com. (2021). Diversity. Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/diversity ↵

- Adapted from LearnRidge. (2021). History - Slavery, Entrenched Racism, and Black Activism. In Supporting Survivors of Sexual Violence: A Nova Scotia Resource. https://nscs.learnridge.com/topic/anshistory/ ↵

- Lorde, A. (1984/2007). Learning from the 60s. In Sister outsider: Essays and speeches by Audre Lorde (pp. 134-144). Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press. Quotation taken from p. 138. ↵

- Southbank Centre. (2016, March 14). Kimberlé Crenshaw - on intersectionality - keynote - WOW 2016 [30.46]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DW4HLgYPlA ↵

- Barnett, P. E. (2013, Summer). Unpacking teachers' invisible knapsacks: social identity and privilege in higher education. Liberal Education, 99(3), 30. ↵

- Curry-Stevens, A. (2007). New Forms of Transformative Education Pedagogy for the Privileged. Journal of Transformative Education, 5(1), 33-58. DOI: 10.1177/1541344607299394 ↵

- University of British Columbia & Queen's University. (n.d.). Module 4: Implicit Bias. In Inclusive Teaching: Equity, Diversity & Inclusion in Teaching and Learning [online curriculum] https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/31444/pages/4-implicit-bias?module_item_id=1637573 ↵

- Characteristics adapted from University of British Columbia & Queen's University. (n.d.). 4.1 Characteristics of Implicit Bias. In University of British Columbia & Queen's University's Inclusive Teaching: Module 1: Power, Privilege and Bias. [online curriculum]. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. ↵

- Harvard University. (2011). Project implicit. https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html ↵

- Kendi, I. (2019). How to Be an Antiracist. (p.47) One World: New York. ↵

- Hughes-Hassell, S., Rawson, C. H., & Hirsh, K. (2019). Module 4: Implicit Bias & Microaggressions. In Hughes-Hassell, S., Rawson, C. H., & Hirsh, K. (Eds.), Project READY: Reimagining equity and access to diverse youth [online curriculum]. https://ready.web.unc.edu/section-1-foundations/module-4-implicit-bias-microaggressions/ ↵

- Freire Institute. (n.d.). About Us. https://www.freire.org/about/ ↵