8 Student Voice and Agency

Learning Objectives

- Articulate definitions of student voice and student agency

- Relate the concepts of voice and agency to how your students experience education content, spaces, and relationships

- Explore a new framework for understanding student voice and agency

- Connect what you’ve learned to your professional practice to provide opportunities for all students to develop and express their voices

Introduction Video

Examples of Student Voice and Agency

George Swaniker: Let people tell their stories

Read

Two-Eyed Seeing: Blending perspectives and protecting Unama’ki. A profile of NSCC student Kieran Wasuek Johnson on the NSCC website.

Sharing Black stories, amplifying Black voices, a 2021 NSCC blogpost about NSCC Radio Television Journalism students shining a light on a land ownership issue in the historically-Black community of North Preston with the launch of the film Untitled: The Legacy of Land in North Preston.

|

Reflect |

- What does student voice and agency mean to you?

- What levels of student voice and agency do you think are demonstrated in the article?

- What factors do you think made it possible for these students to exercise their voice and agency?

|

Throughout the module, we use this icon to suggest times to reflect on a concept, your professional practice, or yourself. We hope these questions help spark your thinking in new and creative directions. |

Reflecting on Identity

Reflecting on our identities and acknowledging how they manifest in our education practice is ongoing work. Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your own identities and how they relate to this module.

Consider your own personal learning about the topic. Where do you fall on the following continuum?

| I have not yet begun thinking about this |

I have started to learn more about this. |

I am actively thinking and learning about this. |

I am applying my new learningand remain committed to further reflection and growth. |

|---|---|---|---|

- In what ways does my social and geographical location influence my identity, knowledge, and accumulated wisdom? What knowledge am I missing?

- What privileges and power do I hold? In what ways do I exercise my power and privilege?

- Does my power and privilege show up in my work? If so, how?

- Am I aware of if/how my biases and privileges might take up space and silence others?

It’s important to realize that you do not have to be an expert on these topics to actively engage in self-reflection and conversations with students. Being an equity-centred educator requires regular and repeated reflection on the Eurocentric assumptions, knowledges, and ways of being that guide our thoughts and actions.

Being aware of which knowledges, experiences, and ways of being in the world are privileged in your discipline, classroom, and institution are a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is legitimate action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Unpacking Language: Key Terms

In this section, you’ll engage with several important words and ideas related to student voice and agency. We will only skim the surface of these important, complex, and deep-seated issues.

The purpose of this section is to establish a shared understanding and vocabulary to build on in future modules. This work is essential but is also sometimes uncomfortable. This should not deter us from doing it.

As a staff or faculty member, recognizing and addressing the meanings of these words in your planning and reflection is important. The more clearly a term is articulated, the more likely you are to develop the knowledge and skills to use it. You will also feel more comfortable talking about and using these words in your teaching and interaction with students.

Write:

Take a couple of minutes to write your understanding of the following key terms (don’t worry about getting it right or perfect; the idea is to respond quickly):

- student voice

- student agency

Review

Now, review the following definitions to see how your understanding of key terms aligns:

Student Voice:[1]

In education, voice refers to the values, opinions, beliefs, perspectives, and cultural backgrounds of the people in an educational institution and the community it’s in. Voice can also mean the degree to which those values, opinions, beliefs, and perspectives are considered, included, listened to, and acted upon when important decisions are being made.

Voice is often misunderstood as being unified within a group; student voice is an excellent example of this. While post-secondary students may have many interests in common, such as keeping tuition affordable, they come from a wide range of perspectives and backgrounds. This means that in any student body, there will be many student voices.

The concept of voice is sensitive to, inclusive of, and predicated on intersectional layers of diversity, including individual, racial, socio-economic, and cultural diversity. This also means that one person from an equity-seeking group can’t represent or speak for the interests of all people in that group. For example, one 2SLGBTQ+ student activist does not necessarily speak for all 2SLGBTQ+ students, nor should they be assumed to.

Student voice can be seen as an alternative to more traditional forms of governance or instruction in which school administrators and teachers may make unilateral decisions with little or no input from students.

Student voice has two parts:

- Students have important stories to tell. In telling their stories, they provide insight and enrich the narrative about what it means to be a student, particularly a student associated with an equity-seeking group or groups.

- Student voice must include social action. This supports student agency and positions students as agents of change in their schools and communities.

Student Agency

The concept of student agency… is rooted in the principle that students have the ability and the will to positively influence their own lives and the world around them. Student agency is thus defined as the capacity to set a goal, reflect and act responsibly to effect change. It is about acting rather than being acted upon; shaping rather than being shaped; and making responsible decisions and choices rather than accepting those determined by others.

When students are agents in their learning, that is, when they play an active role in deciding what and how they will learn, they tend to show greater motivation to learn and are more likely to define objectives for their learning. These students are also more likely to have “learned how to learn” – an invaluable skill that they can and will use throughout their lives. Agency can be exercised in nearly every context: moral, social, economic, creative.[2]

Student agency can include:[3]:

- Influencing course and program topics, activities, and final products

- Participating in development, policy, and programming decisions

- Sharing ideas about — and solutions to — problems in education spaces and communities

- Collaborating with other students, faculty, and staff to engage in research, social action, and institutional change

- Enhanced motivation for learning

For students, having a voice is the first step in establishing agency and making an impact on themselves, their institutions, and society. Many students need our support and allyship to amplify their voices and make change for themselves and their communities. Equity-centred practices are part, but not all, of that picture.

|

Reflect |

Brainstorm a list of topics and concerns important to your students — issues they care about and that impact their lives.

- How do your students use their voices to raise these topics and concerns? What might be some of the barriers that would stop them?

- Can you think of any examples of student agency influencing program or course content or change on your campus?

- How do student voice and agency intersect with different aspects of student development, in your experience?

Barriers to Student Participation

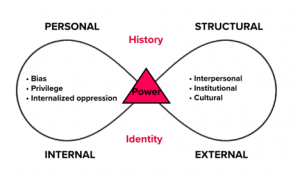

Four Layers of Student Voice and Agency

Personal: Individual Voice and Agency

- Show up as fully themselves at school

- tell their own stories- and be heard

- speak up for and advocate for themselves

- prepare to engage on other forms of voice and agency

- feel a sense of belonging as individuals

Interpersonal: Relational Voice and Agency

- approach and build relationships with faculty and student services staff

- work collaboratively with faculty, student services staff, and other students on important issues

- share and demonstrate their own ways of knowing

- feel a sense of belonging in relationships with others

Institutional: Institutional Voice and Agency

- have input on programming and curiculum

- see themselves reflected in content resources and spaces

- participate in developing policy and programs

- feel a sense of belonging in their institution

Cultural: Community Voice and Agency

- transfer their sense of vice and agency and the skills they have developed to the world outside their institution.

- engage in public discourse and social action for positive change

- feel a sense of belonging in the world

Activity

Choose one of the following articles and answer the reflection questions.

- Finding Her Voice, a 2020 NSCC blogpost about NSCC automotive and repair student Gizelle de Guzman’s journey to becoming a mental health advocate. Trigger Warning: This article contains references to suicide.

- Black Citadel High School students get a glimpse into nursing by Sherri Borden Colley posted on CBC News, May 15, 2019. This story is about the Community of Black Students in Nursing, a student-led group working to encourage Black Nova Scotian students in nursing careers.

- Students in Halifax walk out in support of Wet’suwet’en land defenders by Robert Devet in The Nova Scotia Advocate, March 4, 2020.

- Divest holds protest during open house by Zoe Hunter in The Argosy, March 5, 2020. Divest MtA is a group of Mount Allison University student activists dedicated to promoting fossil fuel divestment at their school

|

Reflect |

- What levels of student voice and agency do you think are demonstrated in the article?

- What factors do you think made it possible for these students to exercise their voice and agency?

- How does the story influence your own understanding and development as a faculty and staff member?

What does cultivating student voice and agency look like?[4]

During Discussions

- Pay attention and react to trends in conversations. Who is speaking and who isn’t? Why? How can you make space for more people to participate?

- Listen to, understand, and empathize with different ways of knowing , diverse life experiences, and perspectives.

- Structure discussions to bring all voices into the conversation. Give time for participants to process individually or with a partner before bringing the whole group together.

- Set group agreements – norms for communicating – in advance.

- Build a network of colleagues and advisors of different identities and perspectives for support planning, facilitating and reflecting on discussions.

- Invite contributors from a range of social identities and positions into your program or classroom.

- Go to where the learning is, whether it is in the activity you planned or the supercharged conversation that arises out of the discussion.

Group Work and One-on-One

- Acknowledge that students come from diverse social locations with different relationships to Euro-Western ways of thinking and knowing.

- Set group agreements before starting to collaborate.

- Consider practices such as Council Practice or Talking Circle, where each person gets a chance to speak, if they choose to.

- Allow students choice (when possible) and find out what supports they need to be successful.

- Listen for understanding, ask questions for clarification.

- Summarize the main points or next steps.

- Invite the students reflections.

Tell and hear counterstories[5]

Providing opportunities for students from equity-seeking groups to engage in counterstorytelling can be a powerful way to cultivate voice and agency.

“Counterstorytelling is “a method of telling the stories of those people whose stories are often not told,” especially those who do not belong to the dominant white, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied culture.[6].

Counterstorytelling not only ensures that the voices of BIPOC and other marginalized youth are heard, but it also validates their life experiences, provides a venue for them to share their own narratives and community wealth, and serves as a powerful way to challenge and subvert the versions of reality held by the privileged.

Richard Delgado teaches civil rights and critical race theory at University of Alabama School of Law and suggests that telling and hearing counterstories can help students[7]:

- Heal through acknowledging and understanding the historic oppression and persecution their community has faced

- Realize that other members of their community have similar feelings and experiences and that they are not alone

- Stop blaming themselves or their community for being considered marginalized

- Construct narratives that challenge the dominant narrative

Students who are not members of equity-seeking groups also benefit from hearing counterstories, because it helps them decentre their way of seeing the world and consider that there are many other ways to learn and be.

Ask and listen to students!

This might seem obvious, but one of the easiest and most important things you can do is ask students what they need to succeed. There are many ways to do this, including:

- Engaging one-on-one or in small groups with students and getting to know them

- Giving students an opportunity to make suggestions and give feedback anonymously

- Co-creating learning experiences and objectives with students

- Pay attention to who is struggling to connect with others, to communicate, to participate. Reach out to see if you can help.

What are the strengths of the student voice?

Tianyuan Yu: Using the Council Practice or Talking Circle to hold space for all students to contribute

Different ways to solicit and gather student voice

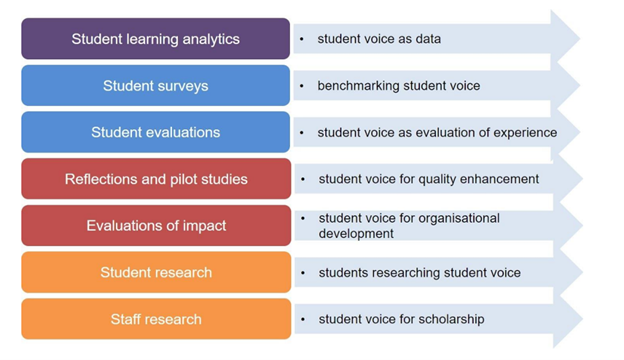

Liz Austen identified seven directions for institutional research to solicit and gather student voice:[8]

- Student learning analytics – student voice as data

- Student surveys – benchmarking student voice

- Student evaluations – student voice as evaluation of experience

- Reflections and pilot studies – student voice for quality enhancement

- Evaluations of impact – student voice for organisational development

- Student research – students researching student voice

- Staff research – student voice for scholarship

Students as Partners

Involving students as partners could include:

- Students as co-researchers of our practice

- Students as co-educators

- Students as collaborators

- Students as co-creators

|

Reflect |

- How can you encourage your students to create counterstories?

- What would your students need to feel safe sharing their concerns or needs?

- What are some things you already do to cultivate student voice and agency?

- What would you like to add to your repertoire?

Sharing and Negotiating Power with Students

I entered the classroom with the conviction that it was crucial for me and every other student to be an active participant, not a passive consumer… education that connects the will to know with the will to become. Learning is a place where paradise can be created.

– bell hooks[9], African American academic, feminist, and social activist

The idea of sharing decision-making and co-creating success with students is relatively new. The traditional view of education positions teachers, administrators, and staff members as authorities. In this view, students are passive receivers of knowledge and rules, and must adapt to the ways of the institution.

The institutional structures we operate in were designed to reinforce an inequitable hierarchy of power and privilege — one we now work to challenge and transform. Student voice and agency is key to this transformation.

Student Unions and Associations

Student unions are among the most important vehicles for student voice and agency in Canada. Elected by the student body to represent all students at the institution in matters of policy and campus issues, student unions are dedicated to social and organizational activities for, and representation and academic support of their membership. Student unions also provide a range of campus services, and advocate for students locally and nationally.

They can also act on behalf of students on matters such as:

- Academic appeals

- Student discipline cases such as plagiarism and cheating

- Residential tenancy issues

- Parking disputes

- Library fine appeals

- Requests for information

Many student unions in Canada are politically active, getting involved in a wide range of on-campus and community issues.

What can you do?

- Take the time to tell your students what the student union is and what it can do for them. Include specific examples of why students should care about the student union

- Encourage your students to get involved in their student union; tell them specifically how to get involved

- Include links and information about the student union on your website, LMS, and syllabi

- Direct students with concerns to the appropriate student union representative

- Invite student union representatives into your class

Read

Dalhousie student faces backlash for criticizing ‘white fragility’ of Canada 150: ‘Act of ongoing colonialism’ by Brett Bundale in The National Post October 21, 2017.

Faculty and staff accountability

Equity is a shared responsibility. Students need to know that you’re learning, too.

Checking in with students one-on-one or through tools like exit slips — short written student responses to questions posed after classes, programs, or other interactions are great ways to build relationships and check in. This is the key to students feeling they can share, voice their concerns and be their authentic selves.

What can you do?

- Demonstrate your accountability by being transparent about your own learning around equity, diversity, and inclusion

- Review your reflections and learning from previous modules, especially Module 2: Personal Privilege and Bias

- As a lifelong learner, share what you’ve learned and how your practice has changed — with each other, with students, with family and friends

- Integrate your own reflections and learning into class discussions

- Invite student feedback specifically about your professional practice as it relates to equity, diversity, and inclusion. If appropriate, find ways for students to give feedback anonymously

- Communicate clearly to students that they can approach you if they have concerns around equity, inclusion, or accessibility

Institutional accountability

Power dynamics in education are intimidating. Whether an issue is personal, interpersonal, institutional, or community-focused, students may feel confused, overwhelmed, and disempowered.

Many, if not most, students don’t know where to go or who to approach to advocate for themselves, their group, or their community.

As a faculty member or student services professional, you can amplify student voice and agency by being a resource and a source of encouragement.

What can you do?

- At the beginning of each course, program, or relationship, communicate clearly to your students that there are resources, policies, and procedures to support equity at the institution

- Give specific information and links on your own website, LMS, and syllabi

- Give specific information about your campus’s accessibility services

- Be clear that students can approach you in confidence with questions and concerns about institutional inequities, and that you will help point them in the right direction

- Be honest if you don’t know what the next step might be for a student with a concern. Help them find out

- You don’t have to know everything and be an expert — commit to listening, learning, and guiding

The Navigating Courageous Conversations module covers in more detail how you can create a climate of mutual understanding and co-learning while ensuring that challenging, uncomfortable, and sometimes difficult conversations can still happen.

|

Reflect |

Consider what you’ve learned so far in this module about student voice and agency.

- Revisit the list you made of topics and concerns important to your students

- Thinking about the four layers of student voice and agency, brainstorm a list of ways you can work with students to cultivate their voices and express their agency. Remember to think collaboratively and focus on student leadership. Think creatively and boldly

Reflecting on Systems

Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your institution as a system and how it relates to this module. Think about the written and unwritten rules, policies, procedures, practices, and traditions that define your institution.

|

Reflect |

Reflect on and write a few lines answering these questions:

- Who is welcomed and can fully participate?

- Who may be excluded, discriminated against, or denied full participation?

- Whose norms, values, and perspectives does the institution consider to be normal or legitimate? Whose does it silence, marginalize, or delegitimize?

- Who inhabits positions of power within the institution?

- Whose experiences, norms, values, and perspectives influence an institution’s laws, policies, and systems of evaluation?

- Whose interests does the institution protect?

Systems of Inequity

Thank you for taking the time to reflect on your own institution in relation to this module. Being aware of the policies, procedures, practices, and traditions and how they intentionally or unintentionally privilege some groups over others is a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is real action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Conclusion

Summary

“For voice to be meaningful, there must be those willing to listen.” Pedro Noguera, Distinguished Professor of Education at the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies and Faculty Director for the Center for the Transformation of Schools at UCLA.

Consider who is listening to your students. Community leaders? Government policymakers? Your institution? You? Look for people and organizations within your institution and in your community who are willing and ready to listen to the voices and ideas of students — and connect your students to them.

|

Reflect |

Think of three actions you can take right away to make and hold space for students whose voices and agency are compromised by inequities and exclusion:

- What resources, strategies, or skills can you help your students develop?

- What platforms can you make available for students to speak their truths and share their ideas for change?

Learn More

Read:

Theorizing Africentricity in Action: Who We Are Is What We See, an MSVU compilation edited by Delvina Bernard and Dr. Sue Brigham.

Academic Well-Being of Racialized Students, by Benita Bunjun, associate professor at Saint Mary’s University

Engaging Student Voices in Higher Education: Diverse Perspectives and Expectations in Partnership

Editors: Simon Lygo-Baker, Ian M. Kinchin, and Naomi E. Winstone

Student Voice in Higher Education Pedagogy, by Mikaela Clark-Gardner and Erin Campbell – CSU Research Report (Concordia)

Engage:

Teaching Tolerance’s Framework for an Anti-Bias Curriculum includes social justice standards. In addition to helping students develop knowledge and skills related to prejudice reduction, many of the standards support voice and agency.

Try:

7 Ways Colleges Can Help Support Students in Speaking Up by Melissa Ezari in Inside Higher Ed, March 2, 2021. This infographic succinctly details how higher education professionals can support student voice and agency.

Attribution

Unpacking Language: Key Terms paragraphs adapted from University of British Columbia & Queen’s University. (n.d.). 2. Unpacking Language.

In University of British Columbia & Queen’s University’s Module 1: Power, Privilege and Bias. [online curriculum]. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Great Schools Partnership. (2014, December 1). Voice. In The Glossary of Education Reform. CC BY-NC-SA. https://www.edglossary.org/voice/ ↵

- OECD. (2019). OECD Future of education and skills 2030: Conceptual learning framework (p.2) [PDF]. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/student-agency/Student_Agency_for_2030_concept_note.pdf ↵

- Adapted from Hughes-Hassell, S., Rawson, C. H., & Hirsh, K. (2019). Module 19: Student Voice & Agency. In Hughes-Hassell, S., Rawson, C. H., & Hirsh, K. (Eds.), Project READY: Reimagining equity and access to diverse youth [online curriculum]. Retrieved from https://ready.web.unc.edu/section-2-transforming-practice/module-19/ ↵

- Cultivating student voice section is adapted from Hughes-Hassell, S., Rawson, C. H., & Hirsh, K. (2019). Module 19: Student Voice & Agency. In Hughes-Hassell, S., Rawson, C. H., & Hirsh, K. (Eds.), Project READY: Reimagining equity and access to diverse youth [online curriculum]. CC BY. Retrieved from https://ready.web.unc.edu/section-2-transforming-practice/module-19/ ↵

- Cultivating student voice section is adapted from Hughes-Hassell, S., Rawson, C. H., & Hirsh, K. (2019). Module 19: Student Voice & Agency. In Hughes-Hassell, S., Rawson, C. H., & Hirsh, K. (Eds.), Project READY: Reimagining equity and access to diverse youth [online curriculum]. CC BY. Retrieved from https://ready.web.unc.edu/section-2-transforming-practice/module-19/ ↵

- Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2002). Critical Race Methodology: Counter-Storytelling as an Analytical Framework for Education Research (p.26). Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040200800103 ↵

- Delgado, R. (1989). Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative. The Michigan Law Review Association, 87, 2411-2441 ↵

- Austen, L. (2018, February 27). ‘It ain’t what we do, it’s the way that we do it’ – researching student voices. Wonkhe. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/it-aint-what-we-do-its-the-way-that-we-do-it-researching-student-voices/ ↵

- hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom.(p. 14). Routledge: New York. ↵