6 Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Practices

Learning Objectives

- Articulate an expanded awareness of the concepts and theoretical frameworks around cultural relevant pedagogy and practices (CRP), including critical race theory, anti-racist and anti-oppressive, and social justice theories.

- Reflect on how your cultural identities and experiences intersect with other cultural identities and experiences.

- Reflect critically on your professional practice to incorporate different world views into your own frame of reference.

- Connect the principles and practice of CRP to your professional practice, and strategies for implementing them.

Why is Culturally Relevant Pedagogy Important?[1]

Gloria Ladson-Billings (1994) introduced the concept of culturally responsive teaching. She saw it as a way to maximize students’ academic achievement by integrating their cultural references in learning environments. Since then, a deep field of research has developed around CRP, including important work by leaders like Geneva Gay, Sonia Nieto and Zaretta Hammond.

Culturally responsive/relevant pedagogy and practices (CRP) is a powerful way to reach ALL students. Here’s why:

It raises expectations for all students. CRP moves away from approaching instruction with a deficit mindset. (A deficit mindset would focus on what a student can’t do.) Instead, CRP identifies students’ assets and uses them to create rigorous, student-centred instruction. CRP builds relational competence. It validates the assets every student brings into the classroom and creates a community of learners committed to social justice.

Students are validated and empowered. With CRP, students tie their learning to their cultures, experiences, interests, and the issues that impact their lives. When students see themselves represented (through knowledge, visually, and physically) in the curriculum, they feel like they belong. They’re more likely to develop the trust it takes to build a relationship with a teacher. Brain science tells us that this sense of belonging makes learning easier and builds students’ self-confidence.[2]

It builds cultural competence. Inclusive pedagogy and practices enhance student learning. It helps both you and your students understand different perspectives and worldviews, appreciate others’ strengths, and build empathy. CRP can also help you reflect on how your own identity and experiences impact your attitudes, pedagogies, and practices.

It works with UDL to create equity for all students. CRP and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) work together to create equitable learning for all students. Both approaches include the use of students’ backgrounds and high expectations by leveraging students’ strengths. Both use practices that are student centred.

CRP in Practice

In March 2019, the Kingstec L’nuek Alliance hosted their second annual Tribute to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two-Spirited people. The event began with the grand reveal of a four-foot-tall steel red dress built by Heavy Duty Equipment / Truck & Transport Repair students Alex Bent and Ben Able, with support from their instructor Dave Myre.

This project is a beautiful demonstration of how awareness of Indigenous realities of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls can be woven into just about any subject — in this case, welding. It shows how the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge and perspectives doesn’t have to take time away from an already busy schedule; it can be the means through which course outcomes are met.

|

Reflect |

Can you think of an example from your own practice, your colleagues, or your campus?

In these examples:

- How did faculty support the process?

- What was the impact on students?

- What is your biggest take-away?

Introduction Video

|

Throughout the module, we use this icon to suggest times to reflect on a concept, your professional practice, or yourself. We hope these questions help spark your thinking in new and creative directions. |

Reflecting on Identity

Reflecting on our identities and acknowledging how they manifest in our education practice is ongoing work. Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your own identities and how they relate to this module.

Consider your own personal learning about the topic. Where do you fall on the following continuum?

| I have not yet begun thinking about this |

I have started to learn more about this. |

I am actively thinking and learning about this. |

I am applying my new learningand remain committed to further reflection and growth. |

|---|---|---|---|

- In what ways does my social and geographical location influence my identity, knowledge, and accumulated wisdom? What knowledge am I missing?

- What privileges and power do I hold? In what ways do I exercise my power and privilege?

- Does my power and privilege show up in my work? If so, how?

- Am I aware of if/how my biases and privileges might take up space and silence others?

It’s important to realize that you do not have to be an expert on these topics to actively engage in self-reflection and conversations with students. Being an equity-centred educator requires regular and repeated reflection on the Eurocentric assumptions, knowledges, and ways of being that guide our thoughts and actions.

Being aware of which knowledges, experiences, and ways of being in the world are privileged in your discipline, classroom, and institution are a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is legitimate action to combat the impacts of oppression.

What is Culture?

Culture is “an amalgamation of human activity, production, thought, and belief systems.”[3]

Culture is a dynamic system of social values, cognitive codes, behavioural standards, worldviews, and beliefs used to give order and meaning into our own lives as well as the lives of others… Because teaching and learning are always mediated or shaped by cultural influence, they cannot ever be culturally neutral.

– Geneva Gay[4]

Culture goes much deeper than typical understandings of ethnicity, race and/or faith. It encompasses broad notions of similarity and difference, and it is reflected in our students’ multiple social identities and their ways of knowing and of being in the world. We must be responsive to culture to ensure all students feel safe, welcomed, accepted, and inspired to succeed in a culture of high expectations for learning.

Culture manifests through all our expressive behaviours including thinking, relating, speaking, writing, performing, producing, learning, and teaching.[5]

Culture Iceberg

Edward T. Hall: Culture Iceberg

Hall’s cultural Iceberg outlines the differences between surface culture (the aspects of culture that are explicit, visible, and taught) and deep culture (habits, assumptions, understandings, assumptions- things we know but can’t easily articulate).[6]

Use the slider on the following image to review some examples of surface and deep culture. Use the questions to reflect on your own or other cultures to discover more about this concept.

Now try the following Cultural Iceberg drag and drop activity to see if you can recall those aspects of culture that are either easy or difficult to see.

|

Reflect |

- Which questions were harder to answer?

- What surface culture elements influence the way you think, relate, speak, write, perform, produce, learn, and teach?

- What deep culture elements influence the way you think, relate, speak, write, perform, produce, learn, and teach?

It is important to consider Equity Seeking Groups and the different ways of knowing that students from these diverse communities bring to learning environments. However, this does not mean knowing every single culture in our learning environments but instead seeing student cultural diversity as strengths distinct from the dominant Euro-Canadian culture. It is about using culture to enhance learning rather than as challenges and/or deficits of the student or particular community.

Locating your own social identities and bringing them into the classroom

Tereigh Ewert: Locating your own social identities and bringing them into the classroom

|

Reflect |

Do you articulate your own social positionality when interacting with students? If so, how? If not, why not?

What is Culturally Relevant Pedagogy and Practice?

Culturally Relevant Pedagogy and Practice

Learn More on Culturally Relevant Pedagogy and Practice

Nicole West-Burns: Culturally Responsive and Relevant Pedagogy: The Foundation and Core Components

Tereigh Ewert: Why taking a deficit approach to students is problematic

Listen

Listen to the blogcast contained at the bottom of the article Start with Responsive by Zaretta Hammond.

A foundational premise of Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain is that relationships in the form of learning partnerships are the starting point of becoming culturally responsive as an educator. In this blogcast, Zaretta Hammond talks about the why and how of becoming more responsive starting with these three strategies[7]:

- Humanize your interactions with all students

- Use the Neuroscience of Trust as your first CRP tool

- Practice touching the spirit by igniting positive emotions

|

Reflect |

- In my view, the most important message of these resources is…

- I didn’t realize that…

- For me CRP means…

- What stands out for me as the core components of CRP are…

- The core components I already use in my practice are…

- Core components that I can further develop are…

CRP In Practice[8]

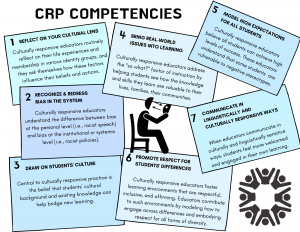

Building on this scholarship, and the CRP competencies developed by New America (think tank and civic innovation platform in the United States), we outline seven core competencies that describe what culturally responsive educators know and do. Reflection questions facilitate further reflection and learning.

CRP Competencies

CRP Competencies

- Reflect on your Cultural Ties

- Recognize and Redress Bias in the System

- Draw on Student Culture

- Bring Real World Issues into Learning

- Model Expectations for all Students

- Promote Respect for Students Differences

- Communicate in linguistically and culturally responsive ways.

Competency 1: Reflect on Your Cultural Lens

Culturally responsive educators routinely reflect on their life experiences and membership in various identity groups, and they ask themselves how these factors influence their beliefs and actions. They understand that they, like everyone, have internalized biases that shape their professional practice and their interactions with students, and colleagues. They understand that they can unknowingly use stereotypes and commit microaggressions if they are not vigilant about how they think and act.

Therefore, these educators diligently work to reflect on their unconscious attitudes and develop cultural competency—that is, understanding, sensitivity, and appreciation for the history, values, experiences, and lifestyles of others. Becoming self-aware can be difficult and uncomfortable, particularly for educators who have never explored their identities.

|

Reflect |

- How does my identity shape my thinking, values and understanding of the world?

- How does my identity differ from students and colleagues? How does it shape my interactions with students and colleagues?

- Do I access resources to deepen my own understanding of cultural, ethnic, gender, and learning differences to build stronger relationships and create more relevant learning experiences?

- Do I have the skills to respond to stereotypes and microaggressions when they happen?

- How can I further develop this competency?

Do

Cultural Competency Assessment This self-assessment tool is designed to explore individual cultural competence. Its purpose is to help you to consider your skills, knowledge, and awareness of yourself in your interactions with others.

|

Reflect |

- What surprised you?

- How did you feel doing the assessment?

Competency 2: Recognize and Redress Bias in the System

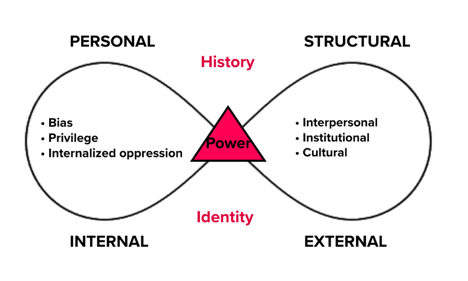

Culturally responsive educators understand the difference between bias at the personal level (i.e., racist speech) and bias at the institutional or systemic level (i.e., racist policies). They seek to deepen their understanding of how identity markers (i.e., those assigned by race, ethnicity, ability, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, and gender, etc.) influence the educational opportunities that students receive.

Bradley Sheppard: The importance of representation and seeing the whole person.

|

Reflect |

- Do I understand the difference between personal privilege and bias and systemic bias and oppression?

- Do I find and use tools and processes that promote self-reflection in order to mitigate behaviors and practices (e.g., racism, sexism, homophobia, unearned-privilege, eurocentrism, etc.) that undermine inclusion and equity in education?

- Do I take leadership with colleagues in influencing institutional culture on issues of race, culture, gender, linguistic background, and socio-economic status?

- How can I further develop this competency?

Competency 3: Draw on students’ culture

Central to culturally responsive practice is the belief that students’ cultural background and existing knowledge can help bridge new learning. Believing this to be true, culturally responsive educators use cultural scaffolding by providing links between new academic concepts and students’ background knowledge that comes from their families, communities, and lived experiences; they regularly use student input to shape assignments, projects, and assessments.

|

Reflect |

- Do the assignments, assessment, and instructional resources I use allow students to see themselves?

- Do I use cultural references, experiences, and knowledges students bring as assets to be connected to/built upon?

- Do I review the instructional resources I use for historical accuracy, stereotypes, cultural relevance, and multiple perspectives?

- How do I seek to learn about my students’ existing knowledge, cultural backgrounds, interests, and issues of concern?

- How can I further develop this competency?

Watch

Learning from Indigenous World-Views from the UBC course Reconciliation through Indigenous Education. Dr. Jan Hare, who is an Anishinaabe from M’Chigeeng First Nation, talks about Indigenous worldviews and how they apply to teaching and learning.

|

Reflect |

- What values or beliefs do you think underlie Western approaches?

- What values or beliefs do you observe in Indigenous educational approaches?

- What are the benefits, for all students, of integrating Indigenous approaches into curriculum?

Competency 4: Bring Real-World Issues into Learning

Culturally responsive educators address the “so what?” factor of instruction by helping students see how the knowledge and skills they learn are valuable to their lives, families, their communities. They ask:

- What does this material have to do with your lives?

- Does this knowledge connect to an issue you care about?

- How can you use this information to take action?

They regularly assign activities, projects, and assessments that require learners to identify and propose solutions to complex issues, including issues of bias and discrimination. They actively seek input from students when planning learning activities and they ensure learning happens inside and outside of the classroom.

|

Reflect |

- How can I guide learners in developing possible solutions to real-world problems?

- How do the projects, assignments, and assessments I use empower and prepare students to solve problems in their lives, their communities, and in the world?

- How does my professional practice connect knowledge to students’ daily lives, including experiences with oppression and injustice?

- Does my professional practice develop students’ self-efficacy, critical consciousness, and motivation to challenge the status quo?

- How can I further develop this competency?

Competency 5: Model High Expectations for All Students

Culturally responsive educators believe all students can achieve high levels of success. These educators understand that students from equity-seeking and other marginalized groups are vulnerable to negative stereotypes about their intelligence, academic ability, and behavior. They understand that these stereotypes can inadvertently influence their pedagogical choices and expectations of students, which in turn influence students’ perceptions about their own abilities.

Culturally responsive educators are vigilant in maintaining their belief that all students can meet high expectations if given proper support and scaffolds, regardless of their identity or past performance. These educators do not accept anything less than a high level of success from all their students and they do not allow students to disengage from learning. Instead, they help students develop high expectations for themselves.

High Expectation Teaching by the Education Hub

|

Reflect |

- How do I communicate that I have high expectations for students of all backgrounds and identities?

- How do I help students develop high expectations for themselves?

- What supports and scaffolds do I provide to ensure that all students are able to meet rigorous outcomes goals?

- How can I further develop this competency?

Competency 6: Promote Respect for Students Differences

Culturally responsive educators foster learning environments that are respectful, inclusive, and affirming. Educators contribute to such environments by modeling how to engage across differences and embodying respect for all forms of diversity. They also help students value their own and others’ cultures and develop a sense of responsibility for addressing prejudice and mistreatment when they encounter it.

|

Reflect |

- How do I create learning environments that are safe, respectful, and inclusive for all students?

- How do I role-model proactive responses to all forms of bias and oppression?

- How do I help students recognize their responsibility to stand up against all forms of bias and oppression in their everyday lives?

- How can I further develop this competency?

Competency 7: Communicate in Linguistically and Culturally Responsive Ways

When educators communicate in culturally and linguistically sensitive ways, students feel more welcomed and engaged in their own learning. Culturally responsive educators seek to understand how culture influences communication, both in verbal ways and nonverbal ways. They allow students to use their natural ways of talking in the classroom.

|

Reflect |

- What is my style of communicating verbally and nonverbally? Does my style of communication differ from that of my students?

- How do my behavioural and communication expectations of students consider varying cultural norms?

- How do I actively work to reduce communication barriers between myself and students?

- How can I further develop this competency?

Connection to Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Both UDL and CRP frameworks focus on:

- Identification and removal of barriers

- High expectations for all learners

- Building and maintaining relationships

- Fostering the learning process

- Connections to the neuroscience of learning

- Building on strengths

- Attitudinal investment and shifts from educators

CRP and UDL work together to create equitable learning for all students. Both approaches include the use of students’ backgrounds and high expectations for learning.

Both CRP and UDL are grounded in neurological science and when implemented, have a positive impact on student learning and wellness.

Reflecting on Systems

Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your institution as a system and how it relates to this module. Think about the written and unwritten rules, policies, procedures, practices, and traditions that define your institution.

|

Reflect |

Reflect on and write a few lines answering these questions:

- Who is welcomed and can fully participate?

- Who may be excluded, discriminated against, or denied full participation?

- Whose norms, values, and perspectives does the institution consider to be normal or legitimate? Whose does it silence, marginalize, or delegitimize?

- Who inhabits positions of power within the institution?

- Whose experiences, norms, values, and perspectives influence an institution’s laws, policies, and systems of evaluation?

- Whose interests does the institution protect?

Systems of Inequity

Thank you for taking the time to reflect on your own institution in relation to this module. Being aware of the policies, procedures, practices, and traditions and how they intentionally or unintentionally privilege some groups over others is a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is real action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Conclusion

Summary

This module builds a foundation for culturally relevant or responsive pedagogy and practices, CRP for short. We developed a shared understanding of CRP concepts and competencies, including:

- Reflecting critically on your professional practice to incorporate different world views into your own frame of reference;

- Articulating an expanded awareness of the concepts and theoretical frameworks around CRP, including anti-racist, anti-oppressive, and social justice theories;

- Reflecting on how your cultural identities and experiences intersect with other cultural identities and experiences; and

- Connecting CRP competencies to your professional practice.

Learn More

Read:

Activism Skills: Land and Territory Acknowledgement by Amnesty International Canada

Tips for Creating an Indigenous Land Acknowledgement Statement by the Native Governance Center, October 22, 2019.

How can I Make the Land Acknowledgement Meaningful? by Dr. Angela Nardozi on her personal blog November 13, 2017.

NAHLA Land Acknowledgement, Template for Personalization, Definitions, and Speaker Protocol by the Northern Alberta Health Libraries Association

Watch

TrillEDU: Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (13:37), Jeffrey Dessources, TEDX

Attribution

CRP Competencies section copied from New America’s “Teacher Competencies that Promote Culturally Responsive Teaching.” (2020). [website]. Shared under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Adapted from Educators Team at Understood. (n.d.) What is culturally responsive teaching? Understood. ↵

- Kaufman, K. (n.d.). Building positive relationships with students: What brain science says. Understood. https://www.understood.org/articles/en/brain-science-says-4-reasons-to-build-positive-relationships-with-students ↵

- Ladson-Billings, G.J. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Education Research Journal, 35, 465-491. ↵

- Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: theory, research, and practice (Third). Teachers College Press. ↵

- Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: theory, research, and practice (Third). Teachers College Press. ↵

- ( 2020, September 2).The Iceberg Model Of Culture And Behavior. https://harappa.education/harappa-diaries/iceberg-model-of-culture-and-behavior/ ↵

- Hammond, Z. (2017, November 17). Start with responsive[blog post and blogcast]. In Culturally Responisve Teaching and the Brain. https://crtandthebrain.com/start-with-responsive/ ↵

- Adapted from Muniz, J. (2020, Sept. 23). Culturally Responsive Teaching: A Reflection Guide. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/policy-papers/culturally-responsive-teaching-competencies/ ↵