3 Equity-Seeking Groups

Learning Objectives

- Articulate an expanded awareness of equity-seeking groups in Nova Scotia.

- Connect how students from equity-seeking groups in Nova Scotia experience daily life with how they experience barriers in post-secondary education.

- Explore your roles and responsibilities as they relate to Nova Scotia legislation as well as equity policy and procedures at your post-secondary institution.

Introduction Video

|

Throughout the module, we use this icon to suggest times to reflect on a concept, your professional practice, or yourself. We hope these questions help spark your thinking in new and creative directions. |

Reflecting on Identity

Reflecting on our identities and acknowledging how they manifest in our education practice is ongoing work. Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your own identities and how they relate to this module.

Consider your own personal learning about the topic. Where do you fall on the following continuum?

| I have not yet begun thinking about this |

I have started to learn more about this. |

I am actively thinking and learning about this. |

I am applying my new learningand remain committed to further reflection and growth. |

|---|---|---|---|

- In what ways does my social and geographical location influence my identity, knowledge, and accumulated wisdom? What knowledge am I missing?

- What privileges and power do I hold? In what ways do I exercise my power and privilege?

- Does my power and privilege show up in my work? If so, how?

- Am I aware of if/how my biases and privileges might take up space and silence others?

It’s important to realize that you do not have to be an expert on these topics to actively engage in self-reflection and conversations with students. Being an equity-centred educator requires regular and repeated reflection on the Eurocentric assumptions, knowledges, and ways of being that guide our thoughts and actions.

Being aware of which knowledges, experiences, and ways of being in the world are privileged in your discipline, classroom, and institution are a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is legitimate action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Unpacking Language: Key Terms

Words matter, and words can have multiple meanings.

In this section, you’ll engage with several important words and ideas related to power, privilege, and bias. We will only skim the surface of these important, complex, and deep-seated issues.

The purpose of this section is to establish a shared understanding and vocabulary to build on in future modules. This work is essential but is also sometimes uncomfortable. This should not deter us from doing it.

As a staff or faculty member, recognizing and addressing the meanings of these words in your planning and reflection is important. The more clearly a term is articulated, the more likely you are to develop the knowledge and skills to use it. You will also feel more comfortable talking about and using these words in your teaching and interaction with students.

Write

Take a couple of minutes to jot down your understanding of the following key terms (don’t worry about getting it right or perfect; the idea is to respond quickly):

- intersectionality

- equity-seeking groups

- resilience

- decolonization

Review

Now, review the following definitions to see how your understanding of key terms aligns:

intersectionality: Is a way of thinking about and understanding how we and our students are shaped and affected when our multiple identities interact and intersect within systems. It allows us to see people, groups, and social problems in the context of multiple discriminations and disadvantages.

equity-seeking groups: Are groups of people that experience oppression and exclusion from society, the economy, and education based on social, physical, cultural, religious, or personal characteristics. The terminology for equity-seeking groups is constantly evolving. You might also see equity-seeking groups referenced as equity groups, equity-deserving groups, or equity-denied groups.

resilience: Means using personal and collective strengths to protect ourselves and our communities in the face of great stressors and/or oppression and build a better future. It is the capacity of individuals and communities to build and recover their strength, spirit, and emotional well-being. Resistance — active and passive acts that fight back against oppression — is an important part of resilience.

decolonization: Is active resistance against colonial powers, and a shifting of power towards political, economic, educational, and cultural independence and power that originate from a colonized nation’s own Indigenous culture. This process occurs politically and also applies to personal, societal, cultural, political, agricultural, and educational deconstruction of colonial oppression.

|

Reflect |

- Which terms did you feel most confident defining? Which ones felt more difficult? Why do you think this is?

- How has your understanding of these terms changed over time?

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is an important part of any discussion about equity-seeking groups. You already learned about intersectionality in Module 2: Personal Privilege and Bias. Using an intersectional approach to teaching and student support is critical to establishing equity in the classroom and in student services.

The concept of intersectionality was articulated by Kimberlé Crenshaw, an American lawyer, civil rights advocate, philosopher, and a leading scholar of critical race theory.

Intersectionality integrates our overlapping personal and social identities and experiences so we can understand the complexity and interconnectedness of the barriers and prejudices we might face — as well as the advantages and privileges we might enjoy.

These interactions happen within interconnected systems and structures of power. Laws, policies, governments, schools, institutions, people, and organizations with social and economic power interact to create interdependent forms of privilege and oppression.

For example, your experiences as an Indigenous woman are informed by intersections of Indigeneity and gender. Your experiences as an African Nova Scotian who uses a wheelchair are informed by intersections of race and ability.

Intersectionality helps us take action on our professional practice to create equitable educational, social, and economic opportunities for our students. It lets us see each other for who we are and how we came to be here.

A People’s Journey

#APeoplesJourney: African American Women and the Struggle for Equality (2:58) produced by the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. The video explains intersectionality.

|

Reflect |

After watching the video…

- What, if any, intersections of privilege do you stand in?

- How have these intersections affected your life?

What is Intersectionality About?

Intersectionality is not simply about adding up or listing identities. It’s about how the world we live in — its policies, its institutions, its structures — has different impacts on us depending on our identities.[1]

Intersectionality also encourages us to leverage our privilege in the spaces and places where we are, in order to lift up others who do not have power, access, and respect in those places and spaces.

Throughout this module, we invite you to consider how being a member of more than one equity-seeking group might affect a student’s life and educational experience. We’ll also offer readings, video clips, and other engagements to help you understand the complexities of identity.

Black LGBTQ activists bring Pride back to its protest roots

Watch: CBC News: The National segment, Black LGBTQ activists bring Pride back to its protest roots June 27, 2020 (4:18).

As protests against police brutality and anti-Black racism spill into Pride month, Black LGBTQ+ activists are drawing attention to the lives and voices often left out of the picture with the phrase “All Black Lives Matter”.

Read

Finding space for Halifax’s LGBTQ2S+ disabled community: Halifax’s popular queer-centred bar is not as inclusive as it may seem by Stephen Wentzell posted September 6, 2019 in the Dalhousie Gazette.

Equity-Seeking Groups in Nova Scotia

The equity-seeking groups described in this section are by no means an exhaustive list of people who are underrepresented, equity-seeking, equity-deserving, or equity groups in Nova Scotia. In addition to people who are Indigenous, African Nova Scotian, racialized, immigrant and newcomer, international, gender- and sexuality-diverse, women, as well as persons with disabilities or who experience barriers to accessibility we might also consider people who belong to certain religious groups, former youth in care, persons who are incarcerated, and women in underrepresented occupations.

Resilience means using personal and collective strengths to protect ourselves and our communities in the face of great stressors and/or oppression and build a better future. Despite living with the effects of intergenerational and historical trauma, members of equity-seeking groups have demonstrated enormous resilience in the face of prejudice, discrimination, and historical and present-day injustice. It’s crucial to recognize, celebrate, and build on this resilience in our professional practice.

As you learn about equity-seeking groups, remember that cultures are complex and changing all the time. They are not static. This applies to cultures as we traditionally think of them, including African Nova Scotian and Indigenous cultures, as well as cultures that have evolved around other shared experiences like being 2SLGBTQ+ or being a person with a disability or who experiences barriers to accessibility, such as those who identify as Deaf or neurodivergent.

Bradley Sheppard: Equity and supports lead to equality for all students

Indigenous students

Mi’kma’ki People

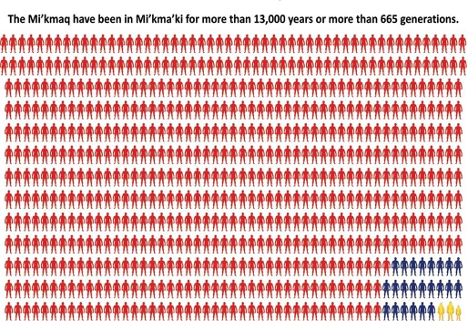

Mi’kma’ki refers to the traditional and current territories of the Miꞌkmaw people and encompasses Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland, as well as parts of New Brunswick, Québec, and Maine. Mi’kmaw people have been in Nova Scotia for more than 13,000 years! Mi’kmaw people have been segregated or centralized into 13 Mi’kmaw communities with more than 16,000 Mi’kmaw people throughout Nova Scotia.

Mi’kmaw communities in Nova Scotia

Interactive Map

Map of Nova Scotia First Nations Communities embedded from Google Maps.

Mi’Kmaki Students’ Challenges

Roger Lewis, Mi’kmaq Cultural Heritage Curator at the Nova Scotia Museum, talks about the difference between contact and colonization (6:10) in Nova Scotia.

Danika Berghamer: How professors’ attempts to censor a presentation oppressed an Indigenous BEd student.

More Than 13000 Years of Mi’Kmaw History

Blue = generations since European contact (23)

Yellow = current generations (3)

Image credit: Mi’kmawey Debert Cultural Centre.

Resistance and Resilience

Mi’kmaw people have lived through many challenges and traumas. The Mi’kmaq, and Indigenous people as a whole, have demonstrated immense personal and cultural resilience and resistance in the face of generations of colonization, violation of treaty rights, and the social and cultural ravages of the residential school system in Canada.

Read

Livelihood or profit? Why an old fight over Indigenous fishing rights is heating up again in Nova Scotia by posted September 23, 2020 on CBC News Nova Scotia.

Peace and Friendship Treaties

On the East Coast, Peace and Friendship Treaties were signed with the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet and Passamaquoddy prior to 1779. Treaties are solemn agreements that set out long-standing promises, mutual obligations, and benefits for both parties. The British Crown first began entering into treaties to end hostilities and encourage cooperation between the British and First Nations. As the British and French competed for control of North America, treaties were also strategic alliances which could make the difference between success and failure for European powers.

Treaty Education Nova Scotia

Treaty Education Nova Scotia Video (13:03) about who the Mi’kmaq are, why treaties are important, what happened to the treaty relationship, and how to reconcile moving forward.

https://www.facebook.com/nsgov/videos/507450066480726/

Treaty Rights in Canadian Constitution

Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution recognizes and affirms existing Indigenous and treaty rights, including the Peace and Friendship Treaties. This means that since 1982, treaty rights are protected by Canada’s Constitution. Unlike later treaties signed in other parts of Canada, the Peace and Friendship Treaties did not involve First Nations surrendering rights to the lands and resources they had traditionally used and occupied.[2]

|

Reflect |

Consider the Peace and Friendship Treaties

- What is your personal relationship to the Treaties — as a settler descendant, Indigenous person, or other social and cultural identity?

- How do dominant higher education structures support practices for the continuation of white supremacy as it relates to Indigenous people in Nova Scotia?

African Nova Scotian Students

Canada’s history of enslavement, racial segregation, displacement, and marginalization of African Canadians has left a legacy of systemic anti-Black racism in Nova Scotia.

African Nova Scotians identify in a number of different ways and come from many backgrounds. Some are descended from generations of formerly enslaved African Black Loyalists and their family and community roots in the province go back more than 400 years. Others might descend from more recent Black immigrants from Africa or the Caribbean or be newcomers from the global Black diaspora.

Black Migration in Nova Scotia

To learn about the peoples of African descent who settled in Nova Scotia from the 1780s to the 1920s view the The Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia’s Black Migration Map for a visual timeline of migration to Nova Scotia.[3]

People who move here from the continent of Africa, the Caribbean, or other parts of the African diaspora have a different lived experience than historical/Indigenous African Nova Scotians born to those who were placed here or came here under duress.

African Nova Scotians/Indigenous Blacks are part of the global diaspora of distinct African-descended peoples who were enslaved and forcibly removed from their homelands on the African continent. African Nova Scotians are descended from generations of African Nova-Scotian Loyalists, Black Refugees, Black Planters, Domestic Workers and Jamaican Maroons.[4]

As a distinct people, African Nova Scotians have collective rights tied to over 52 land-based communities in the part of the unceded territory of Mi’kma’ki known as the province of Nova Scotia. The distinctiveness of African Nova Scotians as a people has been recognized by the United Nations.[5]

Our N.S.: Change for African Nova Scotians

Our N.S.: Change for African Nova Scotians (3:23). This video, from the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission, offers a synopsis of some of the challenges still facing Black Nova Scotians today.

What systemic anti-Black racism looks like in Nova Scotia

Street Checks

A street check is a practice where police stop a person in public, question them, and record their personal information in a police database. Scot Wortley, who holds a doctor of criminology from the University of Toronto, presented his independent report on the issue of police street checks in Nova Scotia in March 2020. “The research clearly demonstrates that police street check practices have had a disproportionate and negative impact on the African Nova Scotian community,” said Wortley. “Street checks have contributed to the criminalization of Black youth, eroded trust in law enforcement and undermined the perceived legitimacy of the entire criminal justice system.”[6]

To learn more, read the 2019 Halifax, Nova Scotia: Street Checks Report published by the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission or watch the video of the press conference held to promote the release of the report. (2:30:05).

Activity: Systemic Anti-Black Racism in Nova Scotia

Choose one of the following articles and complete the following sentences

- In my view, the most important message is…

- I didn’t realize that…

- For me systemic racism means…

- Gentrification

‘Call it what it is — white ignorance’: Gentrification frays the social fabric in Halifax’s North End by The Current posted February 18, 2018 on CBC Radio.

- Environmental Racism

Nova Scotia group maps environmental racism by Moira Donovan posted March 16, 2016 on CBC News.

- Criminal Justice System

N.S. premier apologizes for systemic racism in justice system by CBC News posted September 29, 2020 on CBC News Nova Scotia.

Resistance and Resilience of African Nova Scotians

There is a strong sense of interconnected community and culture amongst African Nova Scotians. This includes values, traditions, and ways of life passed on from previous generations and how each new generation interprets and adapts these to their own lives and communities.

Community and cultural values and traditions are fluid and change over time. They exist within a specific historical and contemporary context of systemic racism, resistance, and survival. Family, extended family, church, spirituality, and community support are all important parts of African Nova Scotian culture and support individual and community resiliency.

While African Nova Scotians have experienced centuries of racism and injustice, they have also been resistant in the face of injustice and never gave up their cultural pride, which builds the resilience to confront subtle, systemic, and ongoing racism.

Students with disabilities and who face accessibility barriers

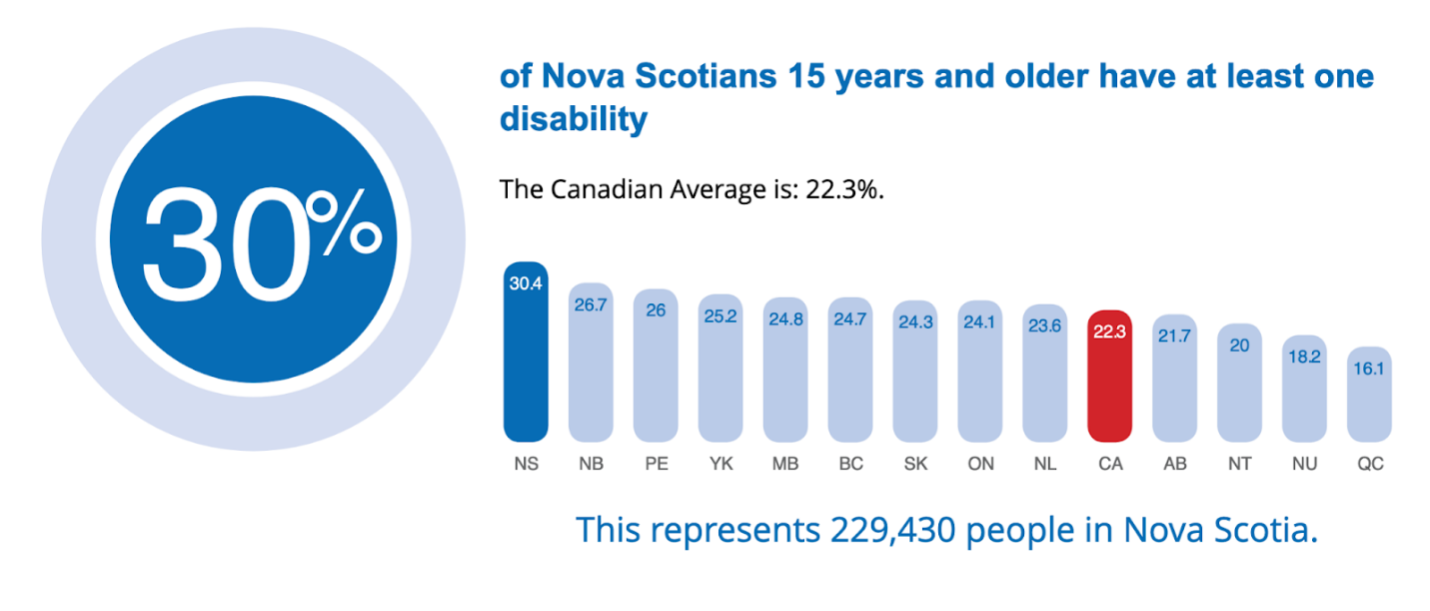

Nova Scotia has a higher percentage of citizens with disabilities than any other province in Canada.

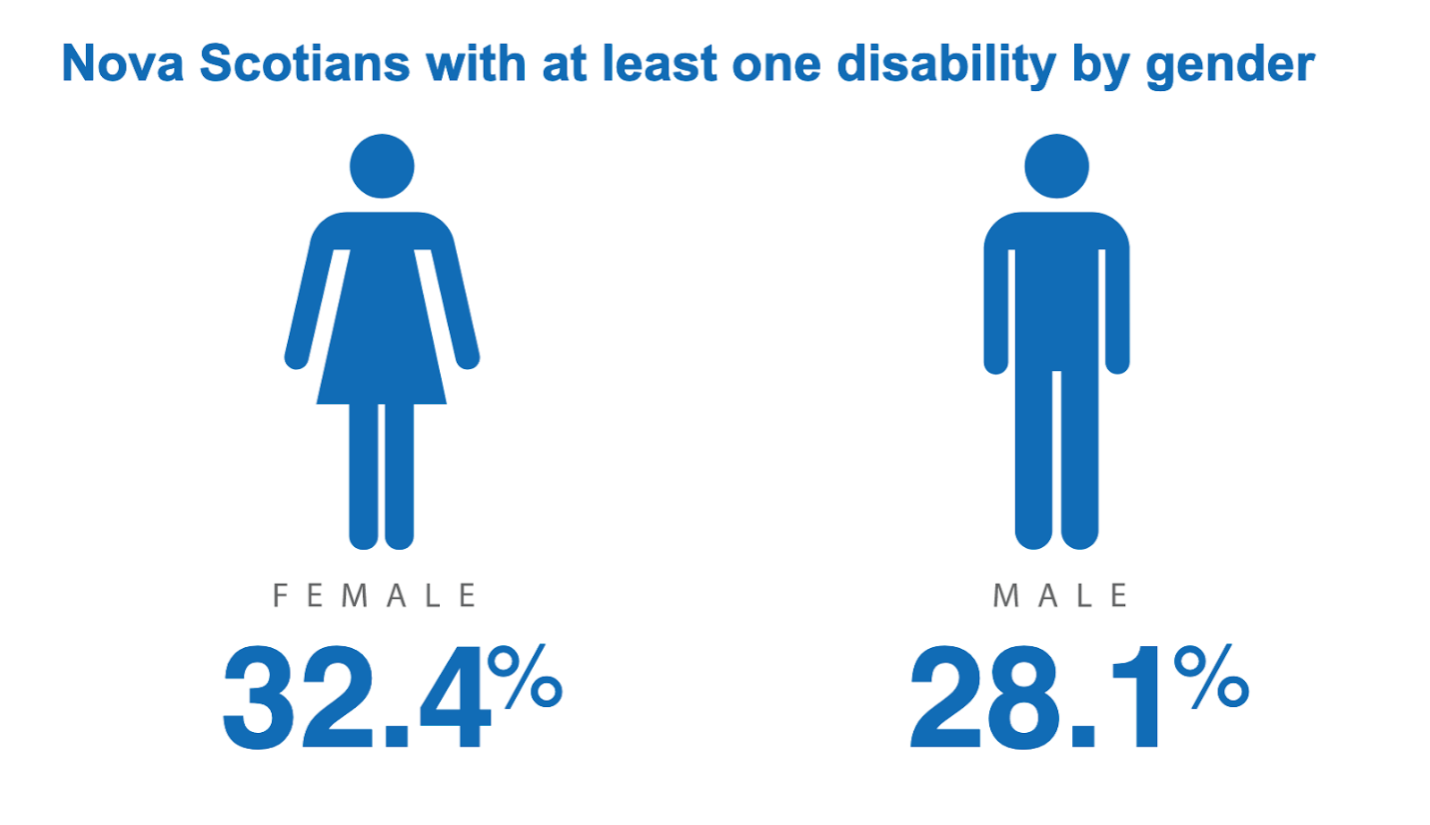

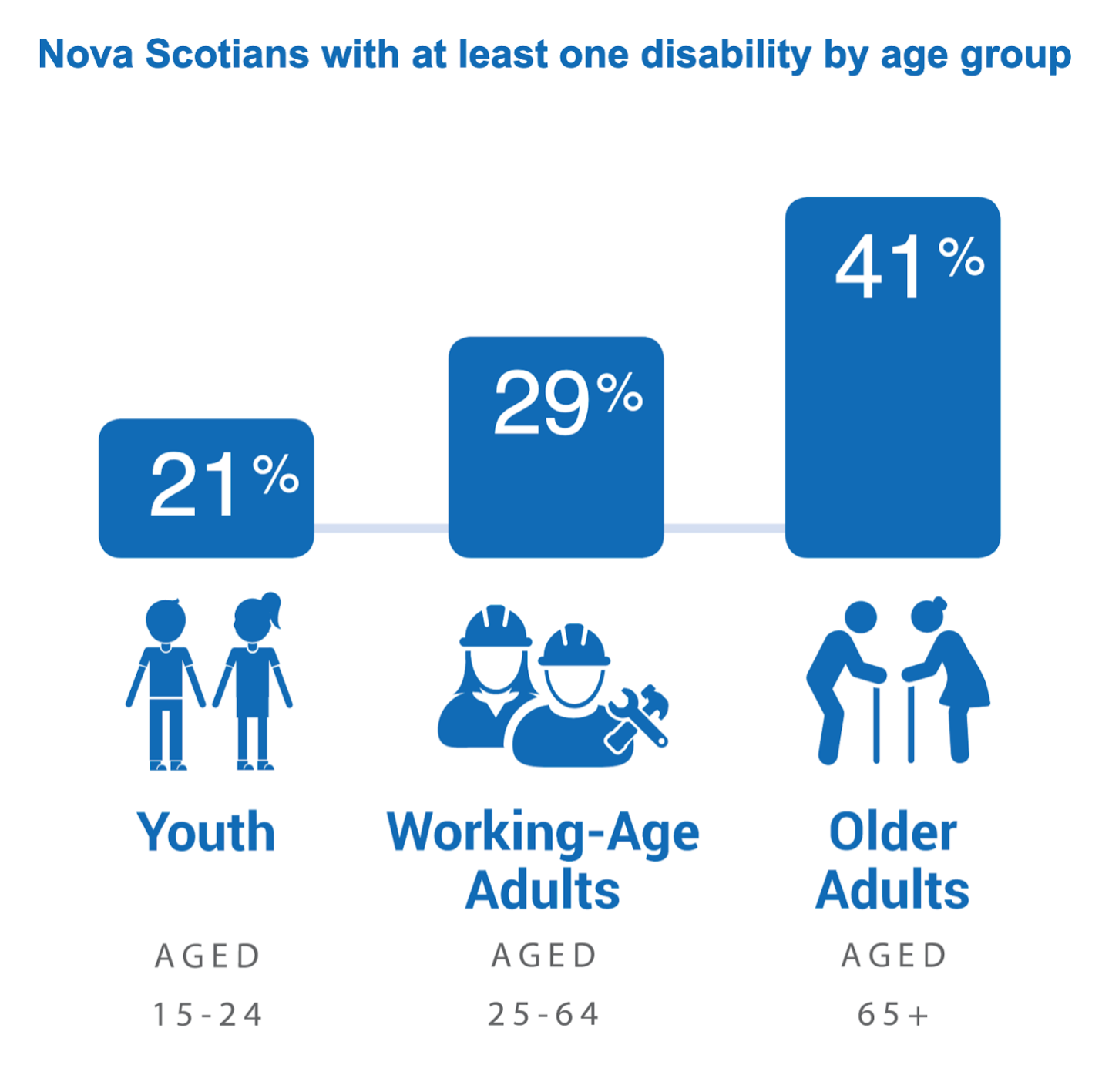

30% of Nova Scotians 15 years and older have at least one disability. The Canadian average is 22.3%. This represents 229,430 people in Nova Scotia. 32.4% of Nova Scotians with at least one disability are female, and 28.1% are male. By age group in Nova Scotia, 21% of youth aged 14-24 have at least one disability, compared to 29% of working-age adults (25-64), and 41% of older adults (65+). [7]

What does the word disability refer to?

The word disability is very broad. It can refer to:

- Physical disability

- Cognitive disability

- Sensory disability such as hearing or visual

- Mental health-related disability

- Learning disability

- Intellectual disability

- Neurological diversity such as autism spectrum disorder or ADHD

There are different ways of looking at disability and barriers to accessibility. The social model of disability says disability is caused by the way society, supports, and the built environment are set up. The medical model of disability says people are disabled by their impairments or differences. It focuses on what’s wrong with the person, not what barriers the person faces.

Ableism is discrimination or social prejudice against people with disabilities or who experience barriers to accessibility, such as those who identify as Deaf or neurodivergent, based on the belief that typical abilities are superior. Disclosing a disability can be stigmatizing. Disability, like other kinds of difference, is not well understood. People with disabilities or who experience barriers to accessibility face constant, daily barriers to participation in education, recreation, and employment.[8]

Not everyone who experiences accessibility barriers identifies as disabled. This might include Deaf students or students who are neurodivergent (e.g., students with autism or ADHD). Ensuring that the built environment, learning materials, and educational approaches are designed for universal access benefits everyone.

Barriers for people with Disabilities

People with disabilities experience many different barriers

- Attitudinal

- Organizational or systemic

- Physical

- In how information, communications, and technology systems are designed

Video: Emily Duffett: Barriers faced by students with accessibility needs

Video: What is the social model of disability?

Social Model Animation

Visible and Invisible Disabilities

Disabilities can be visible or invisible. A visible disability is one you can see. For example, a person with a visible disability might use crutches, have a service dog, or wear a hearing aid. An invisible disability, sometimes called hidden disability, is not immediately obvious. Some examples include depression, learning disabilities, bipolar disorder, chronic illness, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Some disabilities, like autism or a brain injury, might be invisible at first and become more obvious as you interact with someone. People with invisible disabilities still face barriers.

Accessibility and Accommodations

Accessibility means intentionally designing our world to include everyone, regardless of ability. It’s also a way to remove physical, attitudinal, systemic, and technological barriers for people with disabilities.

An accommodation is when an arrangement or adaptation is made so people with all abilities can fully participate — in work, school, social situations, and life.

Disability is vastly diverse and each person experiences their disability differently. In addition to ensuring accessibility in our professional practice, we must provide accommodations to individual students to remove specific barriers. Accommodations need to be flexible and responsive to meet the needs of students with disabilities or who experience barriers to accessibility. Accommodations do not provide an unfair advantage — they improve the playing field.

Quick Facts

Quick Facts on persons with disabilities in Canada by the Canadian Human Rights Commission:[9]

- Bullying: More than 25 percent of persons with disabilities report being bullied at school because of their disability

- Exclusion: 35 percent of persons with disabilities in Canada report being avoided or excluded at school because of their disability

- Taking fewer courses: 37 percent of persons with disabilities in Canada report taking fewer courses because of their disability. This means it takes longer — and costs more — to complete a program

- Early School Leavers: Across Canada, 16.1 percent of youth with disabilities aged 15 to 24 left school because of their impairment

Further Reading

Left Out: Challenges faced by persons with disabilities in Canada’s schools a 2017 report written by the Canadian Human Rights Commission.

Disable the Label: Improving Post-Secondary Policy, Practice and Academic Culture for Students with Disabilities released December 4, 2014 by Students Nova Scotia.

Resistance and Resilience of People with Disabilities

Disability advocates have been fighting for equity in work, education, recreation, and economic participation in Nova Scotia for decades. Despite significant progress in inclusion and accessibility, many stark inequities still exist. Disability can also intersect with many other social identities to create significant barriers and challenges.

Activity Disabilities and Accessibility

Choose one of the following articles and complete the following sentences

- In my view, the most important message is…

- I didn’t realize that…

- For me, ableism means…

- For an article on accessible washrooms in restaurants and other public places read the article: Disability activists say province too slow to act on tribunal order by Jean Laroche posted: October 12, 2018 on CBC News Nova Scotia.

- An article about fighting for service animal rights on public transit: Man with guide dog denied access to Halifax Transit bus by Emily Baron Cadloff posted January 30, 2020 on CTV News Atlantic.

- Read Filmmaker wins award to explore racism, mental health in North Preston by Elizabeth Chiu posted October 18, 2019on CBC News Nova Scotia.

Watch the video interview called Depression, anxiety and ADHD are what Tyler Simmonds calls his ‘superpowers’. North Preston, NS, filmmaker Tyler Simmonds talks about his first film In My Mind, about what it means to live with mental illness as a Black man.

2SLGBTQ+ Students

Your students and colleagues have a range of sexual orientations, gender identities, and gender expressions. You might even witness changes in someone’s gender, gender expression, or sexual orientation over time.

2SLGBTQ+ means two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, and more.

Quick Facts[10]

- Just over 1 in 10 (11 percent) sexual minority Canadians reported that they had been physically or sexually assaulted within the past 12 months in 2018—almost three times higher than the proportion of heterosexual Canadians (4 percent).

- Since the age of 15, sexual minority Canadians (59 percent) were also much more likely than heterosexual Canadians (37 percent) to have been physically or sexually assaulted by someone who was not an intimate partner.

- Transgender Canadians were more likely than non-transgender (cisgender) Canadians to report experiencing violent victimization since the age of 15. They were also more likely to report experiencing inappropriate sexual behaviours in all settings covered by the survey—in public, online and at work—than their non-transgender peers.

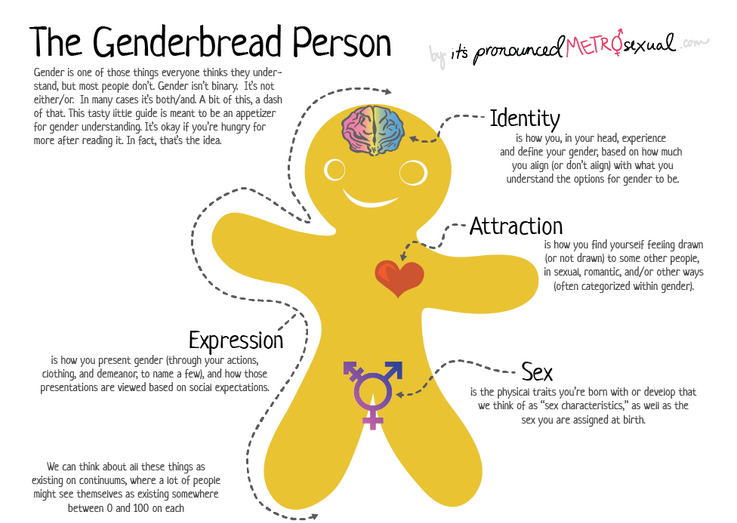

Human Gender and Sexuality

Sexuality and gender diversity are complex concepts. Preferred language and terminology, as well as prevailing attitudes, about gender identity and sexuality have evolved rapidly in Canada over the past few decades and continue to evolve today.

Sexuality describes a person’s identity in relation to the gender or genders to which they are sexually attracted. Sexuality is sometimes called sexual orientation. A person’s sexuality has nothing to do with that person’s gender or gender expression.

Gender refers to the social and cultural characteristics, rather than the biological ones, typically ascribed to men and boys and girls and women. Gender describes socially constructed characteristics. Sex and gender are separate and independent. You can’t tell a person’s gender by looking at them.

Sexual orientation describes to whom a person is sexually attracted. Some people are attracted to people of a particular gender; others are attracted to people of more than one gender. Some are not attracted to anyone.

Gender identity and expression describes the ways a person identifies and/or expresses their gender, including self-image, appearance, and embodiment of gender roles. Sex (male, female, intersex, etc.) is usually assigned at birth based on physical biology. Gender (male, female, genderqueer, etc.) is our internal sense of self and identity. Gender expression (masculine, feminine, androgynous, etc.) is how we embody our gender attributes, presentations, roles, and more.

A person’s sex, sexuality, gender, gender identity, or gender expression might change over the course of their lifetime.

Resistance and Resilience of 2SLGBTQ+ Nova Scotians

The rights of 2SLGBTQ+ Nova Scotians are hard-won. Gay liberation groups in the province have fought for equality for decades, initiating the first nationally coordinated gay and lesbian day of action in 1977, and spearheading a campaign to include sexual orientation in the Human Rights Act.

Our understanding of gender and sexuality is constantly growing. It can feel confusing or overwhelming to keep pace with that understanding, especially if you don’t have family or friends who can help you through sharing their personal experiences.

The most important thing you can do for 2SLGBTQ+ students and colleagues is to be open. Listen to and work to understand their perspectives, honour their experiences, and learn about what will create an inclusive, responsive, and accessible learning and working environment for them. This includes being willing to be corrected.

|

Reflect |

Sex, sexuality, gender, gender identity, and gender expression are complex and evolving topics

- What, if any, misconceptions about gender and sexuality did you grow up with or have you been exposed to? How did you learn more and correct these misconceptions?

- How can you learn more, on your own, without turning to a 2SLBGTQ+ colleague or friend?

Immigrant and international students

Nova Scotia is home to people from all over the world.

Some come here as immigrants. This group includes economic immigrants, refugees, and people who are reuniting with family members. Immigration from other countries is a big contributor to population growth in Nova Scotia. The province received 2,124 immigrants during the second quarter of 2019, the highest level for any quarter for data that begins in 1946.[11]

Others come as international students, many of whom decide to stay in Canada. More than 9,000 international students from over 140 countries attend Nova Scotia’s universities, colleges, secondary schools, and language schools, meaning nearly 10 percent of students on Nova Scotia campuses are from outside Canada.

Read

Record number of international students staying in N.S. after studies by Shaina Luck posted February 7, 2020 on CBC News Nova Scotia.

You likely encounter many new Canadians and international students in your daily practice, as well as first- and second-generation immigrants who were born here but whose parents or grandparents immigrated to Canada. Many newcomers face language and social barriers and often experience discrimination.

Acknowledging, responding to, celebrating, and amplifying what these diverse students bring to the classroom and the institution is critical to offering an equitable education.

Racialized students

During my childhood, in the protective and inclusive domicile of my family, I had no race. My parents taught me the words to describe our heritage and identity. Stepping out of the house, society named me and changed that name as it felt fit. I wonder if European Canadians feel that Canada is like a large family home, where they are included and protected and have no race. I look forward to a future when I feel that again.

-Dreeni Geer, Director of Human Rights and Equity, Lakehead University.[12]

Racialization refers to the processes by which a group of people is defined by their race. Put very simply, racializing people categorizes them according to their perceived race, and imposes racial character on that group as a whole. This racial meaning is then attributed to people’s identity as they relate to social structures and institutional systems, including housing, employment, and education.

These stereotypes, biases, and prejudices are socially constructed and have no scientific or biological basis. Typically, a subordinate or oppressed group is racialized by a dominant group in order to preserve the interests of that group.

Some of the students you encounter daily have been racialized since the day they were born, including Black Nova Scotians and other people of colour who were born or grew up here. Other students might never have experienced racialization before they arrived in Nova Scotia. For them, the experience of being racialized — perceived and treated as other or outside the norm because they are not white — might be new, shocking, and traumatic.

I didn’t know I was Black until I moved to Canada

In societies where white people hold economic, political, and social power — like ours — racialization is both created and maintained by social structures and systems based on race. Historically, these systems include institutions like slavery and social and economic segregation based on skin colour. Today, processes of racialization are evident in the racial inequalities embedded within social structures and systems.

This blog post Racialized is the new Black, and Brown, and… by Dreeni Greer posted on the Ontario Library Association’s Open Shelf website describes a personal experience of being racialized in Canada.

Students perceived to be not white are racialized. This racialization is imposed upon them by the dominant culture, and by the systems they interact with — it may or may not reflect how they see themselves.

|

Reflect |

- Which terms did you feel most confident defining? Which ones felt more difficult? Why do you think this is?

- How has your understanding of these terms changed over time?

Women students

While this module focuses primarily on students who experience racism, homophobia, xenophobia, and ableism, sexism is also a significant intersectional factor facing women in higher education and in the workforce.

In 2019-20, 26,538 (57 percent) students enrolled in higher education in Nova Scotia identified as female, and 19,623 (43 percent) as male.[13] Despite women making up a higher percentage of the student population, women are still more likely to face discrimination based on their gender and choice of discipline. Women are grossly underrepresented in mathematics, computer, and information sciences in Nova Scotia, with almost three times the number of male students pursuing these disciplines as female students. The same is true for architecture, engineering, and related technologies.[14]

According to a 2019 study by Statistics Canada, one in ten (11%) women students reported experiencing a sexual assault in a post-secondary setting during the previous year. A majority (71 %) of post-secondary students witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the past year. Among students, 45% of those who identified as women and 32% of those who identified as men personally experienced at least one such behaviour in the context of their postsecondary studies.[15]

Higher education, like all parts of Canadian society, must grapple with systemic gender discrimination.

Read

63% report experiencing sexual harassment on campus, Ontario survey shows by The Canadian Press, posted on CBC News March 19, 2019.

|

Reflect |

Consider how women students whose identities intersect with other equity-seeking groups might experience multiple oppressions

- How might being a woman make the experience of being a Black student in your area of discipline more — or less — challenging? What about being an Indigenous, racialized, international, or immigrant student, or a student who experiences barriers to accessibility?

- What have you personally observed or experienced about the intersection of being part of an equity-seeking group and being a woman?

Equity Legislation and Frameworks in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia Human Rights Act

The Nova Scotia Human Rights Act[16] prohibits actions that discriminate against people based on a protected characteristic in combination with a prohibited area.

Protected characteristics:

- Age

- Race

- Colour

- Religion

- Creed

- Ethnic, national, or aboriginal origin

- Sex (including pregnancy and pay equity)

- Sexual orientation

- Physical disability

- Mental disability

- Family status

- Marital status

- Source of income

- Harassment (and sexual harassment)

- Irrational fear of contracting an illness or disease

- Association with protected groups or individuals

- Political belief, affiliation, or activity

- Gender identity

- Gender expression

- Retaliation

In addition to protection from discrimination, the Act also prohibits harassment based on any of these characteristics and prohibits sexual harassment in all areas of public life.

Prohibited areas:

- Employment

- Housing or accommodation

- Services and facilities (such as stores, restaurants, or provincially funded programs)

- Purchase or sale of property

- Volunteer public service

- Publication, broadcasting, or advertisement

- Membership in a professional, business or trade association, or employers’ or employees’ organization

Accessibility Legislation in Nova Scotia

In 2017, Nova Scotia passed the Act Respecting Accessibility in Nova Scotia. The aim of the Accessibility Act is to make Nova Scotia inclusive and barrier-free by 2030.

As of April 1, 2020, Nova Scotia universities and the Nova Scotia Community College (NSCC) became public sector bodies under the Accessibility Act. This means they must create multi-year accessibility plans, establish accessibility advisory committees, and comply with accessibility standards.[17]

The Nova Scotia government is working with people with disabilities, as well as public and private sector organizations, to create six standards for an accessible Nova Scotia. The accessibility standards will apply to:

- goods and services

- information and communication

- transportation

- employment

- education

- built environment

These standards are in development, with the first standard development areas being education and the built environment. Compliance with the standards is mandatory and the Act contains fines of up to $250,000 for the most serious cases of non-compliance.[18]

Access by Design 2030: Achieving an Accessible Nova Scotia is the provincial government’s strategy to achieve its goal of an accessible Nova Scotia by 2030. It was developed in consultation with persons with disabilities and their families, service provider organizations, the Accessibility Advisory Board, and representatives from the non-profit, education, health, municipal, and business sectors.[19]

Post-Secondary Accessibility Framework

Nova Scotia’s Post-Secondary Accessibility Framework was collaboratively developed by university and NSCC representatives, faculty, staff, and students, with a focus on first-voice. It was endorsed in June 2020 by the Council of Nova Scotia University Presidents. The purpose of the Framework is to establish a shared vision and commitments for accessibility in Nova Scotia’s post-secondary sector, and to inform the development of institutional multi-year accessibility plans.[20]

The Framework’s vision is for “Nova Scotia post-secondary education institutions [to] provide full and equitable access to education, employment, and services within a collaboratively-developed and values-based commitment to accessibility that prioritizes institutional accountability within a human rights framework.”[21]

The Framework outlines commitments for accessibility in post-secondary education including:

- Awareness and capacity building

- Teaching, learning, and research

- Information and communication

- Goods and services

- Employment

- Transportation

- Built environment

- Implementation, monitoring, and evaluation[22]

|

Reflect |

Connect legislation and social movements to equity seeking policy and procedures at your post-secondary institution

- In what ways has your institution been responsive to this legislation?

- What are three examples of action that you can take in your professional practice to align with the legislation?

Reflecting on Systems

Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your institution as a system and how it relates to this module. Think about the written and unwritten rules, policies, procedures, practices, and traditions that define your institution.

|

Reflect |

Reflect on and write a few lines answering these questions:

- Who is welcomed and can fully participate?

- Who may be excluded, discriminated against, or denied full participation?

- Whose norms, values, and perspectives does the institution consider to be normal or legitimate? Whose does it silence, marginalize, or delegitimize?

- Who inhabits positions of power within the institution?

- Whose experiences, norms, values, and perspectives influence an institution’s laws, policies, and systems of evaluation?

- Whose interests does the institution protect?

Thank you for taking the time to reflect on your own institution in relation to this module. Being aware of the policies, procedures, practices, and traditions and how they intentionally or unintentionally privilege some groups over others is a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is real action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Conclusion

Summary

This module introduced you to some of the equity-seeking groups in Nova Scotia, including:

- Indigenous people

- African Nova Scotians

- Racialized people

- People with disabilities and those who experience barriers to accessibility

- 2SLGBTQ+ people

- Immigrants and international students

- Women

Learning about equity-seeking groups in Nova Scotia is key to developing equity-centred practices that ensure every student has equitable access to education, an equal opportunity to learn and develop, and feels like they belong.

The students you encounter face many systemic inequities and multiple forms of discrimination. Some of these challenges may be obvious to you, and some may not.

Understanding your students’ lived experiences as members of equity-seeking groups is a first step in responding to their individual needs as learners.

Learn More

Watch

Facing Race Halifax (2:35:13). This CBC town hall about racism in Nova Scotia was recorded in 2018. This recording is long but contains a great deal of local context that is critical to developing a deeper understanding of racism in Nova Scotia, particularly Halifax. Mi’kmaq Culture and Resilience (30:00). Six videos sharing examples of Mi’kmaw culture A series of four 4 minute videos that are done in a light-humored kind of way to break attitudinal barriers for people with disabilities (17:47)

Assistive Technology (AT) in the Workplace, Job Accommodation Network, a presentation guide on how to use AT in the workplace, which relates to the classroom as well (20:44)

Read

I was paralyzed 6 years ago and now I struggle with suicide — but not for the reason you think. Scott Jones was attacked outside a New Glasgow, N.S., bar in 2013, which left him paralyzed from the waist down. The musician and music teacher founded the Don’t Be Afraid campaign shortly afterward to encourage others to speak out against homophobia.

Before the Parade: A History of Halifax’s Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Communities, 1972-1984, a 2020 book by Rebecca Rose published by Nimbus Publishing.

Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome a blog post by Dr. Joy DeGruy

Shaping a Community: Black Refugees in Nova Scotia by Lindsay Van Dyk posted November 19, 2020 posted to the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 website.

The story of Africville by Matthew McRae on the Canadian Museum for Human Rights website.

Who Lives Next Door to Your Waste? by Mark Butler and Chantal Gagnon, an article originally published October 16, 2007 in The Chronicle Herald.

Navigating 2 identities: Being black and gay in Nova Scotia posted July 11, 2019 to CBC News Nova Scotia.

A chronological history of Boat Harbour, Nova Scotia by Michael Trombetta and Seyitan Moritiwon posted January 29, 2020 to The Signal.

Practical Guides for Accessibility

Guide to Planning Accessible Meetings and Events, Nova Scotia Accessibility Directorate, Department of Justice

Accessibility at CNIB – guidelines for creating accessible content.

Clear Print Accessibility Guidelines by CNIB Foundation.

Creating Accessible Word Documents Using Word (Win/Mac) by Queen’s University

Creating Accessible PowerPoint Presentations (Win/Mac) by Queen’s University,

Assistive Technology (AT) in the Workplace by the Job Accommodation Network (JAN). A training module that will give you a brief look into what assistive technology is and how it can benefit employees with disabilities.

Attribution

Unpacking Language: Key Terms paragraphs adapted from University of British Columbia & Queen’s University. (n.d.). 2. Unpacking Language.

In University of British Columbia & Queen’s University’s Module 1: Power, Privilege and Bias. [online curriculum]. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Nova Scotia Accessibility Directorate. (n.d.). Prevalence of disabilities in Nova Scotia [infographics]. https://novascotia.ca/accessibility/prevalence/

- University of British Columbia & Queen's University. (n.d.). 4.3 Intersectionality. In Identity Matters: Connecting Power, Privilege and Bias to Anti-Racism Work [online curriculum]. ↵

- Adapted from Government of Canada. (2015, December 10). Peace and Friendship Treaties. Negotiations in Atlantic Canada webpage. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028589/1539608999656 ↵

- Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia. (n.d.). Black migration In Nova Scotiahttps://bccns.com/our-history/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Government of Nova Scotia. (2019). Count us in: Nova Scotia’s Action Plan in Response to the International Decade for People of African Descent 2015–2024. https://adsdatabase.ohchr.org/IssueLibrary/NOVA%20SCOTIA_Action%20Plan%20in%20Response%20to%20the%20International%20Decade.pdf ↵

- Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission. (2017, September 18). Independent expert to examine police street check data [news release]. https://humanrights.novascotia.ca/news-events/news/2017/independent-expert-examine-police-street-check-data ↵

- Statistics Canada. (2018). Table 13-10-0374-01 Persons with and without disabilities aged 15 years and over, by age group and sex, Canada, provinces and territories. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/1310037401-eng ↵

- Eisenmenger, A. (2019, December 12). Ableism 101: What it is, what it looks like, and what we can do to to fix it. Access Living. https://www.accessliving.org/newsroom/blog/ableism-101/ ↵

- Canadian Human Rights Commission. (2017, March 9). For persons with disabilities in Canada, education is not always an open door[press release]. https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/en/resources/persons-disabilities-canada-education-not-always-open-door ↵

- Burczycka, M. (2010, September 14). Students’ experiences of unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault at postsecondary schools in the Canadian provinces. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2020001/article/00005-eng.htm ↵

- Province of Nova Scotia. (2019, September 30). Daily stats [Nova Scotia immigration table]. In Nova Scotia Economics and Statistics. https://www.novascotia.ca/finance/statistics/news.asp?id=15179#:~:text=Nova%20Scotia%20received%202%2C124%20immigrants,data%20that%20begins%201946%20Q1. ↵

- Geer, D. (2018, November 18). Racialized is the new Black, and Brown and …[blog post]. Open Shelf. https://open-shelf.ca/181105-racialized-is-the-new-black-and-brown/ ↵

- Maritime Provinces Higher Education Commission (MPHEC). (2019). Trends in Maritime Higher Education. Annual Digest: University Enrolment 2019-2020. Volume 18, Number 1. https://www.mphec.ca/media/200206/Annual-Digest-2019-2020.pdf ↵

- Maritime Provinces Higher Education Commission (MPHEC). (2019). Table 11: Total Enrolment by Province, Major Field of Study and Gender, 2015-2016 to 2019-2020[PDF]. https://www.mphec.ca/media/198375/Table11_Enrolment_2019-2020.pdf ↵

- Burczycka, M. (2010, September 14). Students’ experiences of unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault at postsecondary schools in the Canadian provinces. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2020001/article/00005-eng.htm ↵

- null ↵

- Enter your footnote content here. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Government of Nova Scotia. (n.d.). Access by design 2030: Achieving an accessible Nova Scotia. Access by Design 2030. https://novascotia.ca/accessibility/access-by-design/ ↵

- Council of Nova Scotia University Presidents (CONSUP). (2020, June). Vision statement in Nova Scotia post-secondary accessibility Framework (p.3). https://www.nscc.ca/docs/about-nscc/nova-scotia-post-secondary-accessibility-framework.pdf ↵

- Council of Nova Scotia University Presidents (CONSUP). (2020, June). Vision statement in Nova Scotia post-secondary accessibility Framework (p.4). https://www.nscc.ca/docs/about-nscc/nova-scotia-post-secondary-accessibility-framework.pdf ↵

- Ibid. p.5-9 ↵