1 Systems of Inequity

Learning Objectives

- Articulate some of the major systems that shape daily life and life outcomes for people in Nova Scotia and Canada. Describe how these systems both create and perpetuate societal inequities.

- Relate your personal experiences as an educator or student support professional to structural inequities in your institution and/or communities.

- Connect how these systems are linked to each other in ways that intensify inequities.

Introduction Video

|

Throughout the module, we use this icon to suggest times to reflect on a concept, your professional practice, or yourself. We hope these questions help spark your thinking in new and creative directions. |

Reflecting on Identity

Reflecting on our identities and acknowledging how they manifest in our education practice is ongoing work. Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your own identities and how they relate to this module.

Consider your own personal learning about the topic. Where do you fall on the following continuum?

| I have not yet begun thinking about this |

I have started to learn more about this. |

I am actively thinking and learning about this. |

I am applying my new learningand remain committed to further reflection and growth. |

|---|---|---|---|

- In what ways does my social and geographical location influence my identity, knowledge, and accumulated wisdom? What knowledge am I missing?

- What privileges and power do I hold? In what ways do I exercise my power and privilege?

- Does my power and privilege show up in my work? If so, how?

- Am I aware of if/how my biases and privileges might take up space and silence others?

It’s important to realize that you do not have to be an expert on these topics to actively engage in self-reflection and conversations with students. Being an equity-centred educator requires regular and repeated reflection on the Eurocentric assumptions, knowledges, and ways of being that guide our thoughts and actions.

Being aware of which knowledges, experiences, and ways of being in the world are privileged in your discipline, classroom, and institution are a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is legitimate action to combat the impacts of oppression.

What Are Society and Culture?[1]

Sociology is the study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups. A group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture is what sociologists call a society. Sociologists study all aspects and levels of society. Sociologists working from the micro-level study small groups and individual interactions, while those using macro-level analysis look at trends among and between large groups and societies. For example, a micro-level study might look at the accepted rules of conversation in various groups such as among teenagers or business professionals. In contrast, a macro-level analysis might research the ways that language use has changed over time or in social media outlets.

The term culture refers to the group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from routine, everyday interactions to the most important parts of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including all of the social rules.[2]

What are Systems?

According to Émile Durkheim, society is a complex system of interrelated and interdependent parts that work together to maintain stability,[3] and that society is held together by shared values, languages, and symbols. He believed that to study society, a sociologist must look beyond individuals to social facts such as laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashion, and rituals, which all serve to govern social life.[4]

What is a social system?

In sociology, a social system is the patterned network of relationships constituting a coherent whole that exist between individuals, groups, and institutions.[1] It is the formal structure of role and status that can form in a small, stable group.[1] An individual may belong to multiple social systems at once;[2] examples of social systems include nuclear family units, communities, cities, nations, college campuses, corporations, and industries. The organization and definition of groups within a social system depend on various shared properties such as location, socioeconomic status, race, religion, societal function, or other distinguishable features.[3][5]

Systems thinking is “understanding how things influence one another within a whole. In nature, systems thinking examples include ecosystems in which various elements such as air, water, movement, plants, and animals work together to survive or perish. In organizations, systems consist of people, structures, and processes that work together to make an organization healthy or unhealthy.”[6]

|

Reflect |

- What social systems are you part of?

- What unintended adverse consequences in those systems can you identify?

- How is your institution a system?

- What role do you play in your institution? How does that relate to your identity and to the identities of other people? How are you engaged in supporting equity and inclusion?

Unpacking Language: Key Terms

Words matter, and words can have multiple meanings

In this section, you’ll engage with several important words and ideas related to power, privilege, and bias. We will only skim the surface of these important, complex, and deep-seated issues.

The purpose of this section is to establish a shared understanding and vocabulary to build on in future modules. This work is essential but is also sometimes uncomfortable. This should not deter us from doing it.

As a staff or faculty member, recognizing and addressing the meanings of these words in your planning and reflection is important. The more clearly a term is articulated, the more likely you are to develop the knowledge and skills to use it. You will also feel more comfortable talking about and using these words in your teaching and interaction with students.

Write

Take a couple of minutes to jot down your understanding of the following key terms (don’t worry about getting it right or perfect; the idea is to respond quickly):

- dominant culture

- social identity

- heteronormativity

- marginalized groups

- oppression

- patriarchy

- power

- prejudice

- systemic oppression

- white supremacy

Review

Now, review the following definitions to see how your understanding of key terms align:

dominant culture: In Canada, dominant culture results from patterns of learned behaviours and values that are shared among members of a group and are transmitted to group members over time; these behaviours and values distinguish the members of one group from another. Even with the extent of racial and ethnic diversity in Canada, the prevailing cultural values are of Christian, European (Western) origin and are perceived as the norm.[7]

social identity: Identity is our image of ourselves and our beliefs about the kind of person we are. Examples of social identities are race/ethnicity, gender, social class/socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, abilities, and religion/religious beliefs.[8]

heteronormativity: A frame of reference that positions heterosexuality as the default and assumes that a man/woman romantic or sexual pairing is the norm.[9]

marginalized groups: Marginalized groups or populations are communities that are systematically discriminated against and socially, politically, and economically excluded by the dominant group or culture. (Groups that have been marginalized is another way of framing this definition).

oppression: The systemic, institutionalized, or individual subjugation of one individual or group by a more dominant individual or group; it can be overt or covert. Put simply, it is an abuse of power that is justified by the dominant group’s explicit ideology. To uphold this unequal dynamic, physical, psychological, social, or economic threats or violence are often used. The term also refers to the injustices suffered by groups that have been marginalized in everyday interactions with members of the dominant group.[10]

patriarchy: The structure of a society in which men have power over women. The unequal power relations that exist between women and men permeate all realms of society — social, legal, political, religious, and economic — thereby systematically disadvantaging women as a whole. Men’s violence against women is a key element of patriarchal structure.[11]

power: The ability to influence others and impose your beliefs.[12] All power is relational, meaning you have power only in relationship to other people. Different relationships either reinforce or disrupt power.[13] Discrimination, including racism, ableism, sexism, and homophobia, cannot be understood without accepting that power is both an individual relationship and a cultural one, and that power relationships are shifting constantly. Power is not always used malignantly and intentionally. Individuals in one culture often benefit from power, over another or others, they don’t even know they have.[14]

prejudice: To “prejudge” an individual or group, consciously or unconsciously, often without legitimate or sufficient evidence.[15] Oftentimes, prejudices are not recognized as stereotypes or false assumptions and through repetition, become accepted as common sense. When backed with power, prejudice results in acts of discrimination and oppression against groups or individuals.[16]

systemic oppression: A series of barriers that disadvantage particular groups of people based on race, religion, gender, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, ability, age, and more. Systemic oppression is often made invisible to those who don’t experience it. It is embedded in social norms and formal institutions such as the police, law, education, and health systems.[17]

white supremacy: The belief that people who see themselves as white are superior to Black, Indigenous, and people of colour and should therefore dominate them. White supremacy perpetuates and maintains social, political, historical, and institutional domination by white people. For example, white supremacy justified the transatlantic slave trade and colonization around the world. Today, it is used to justify entrenched systemic and institutional racism. White supremacy also refers to the political and socio-economic systems that give white people structural advantages over racialized people — both collectively and individually.[18]

|

Reflect |

- Which terms did you feel most confident defining?

- Which ones felt more difficult? Why do you think this is?

- How has your understanding of these terms changed over time?

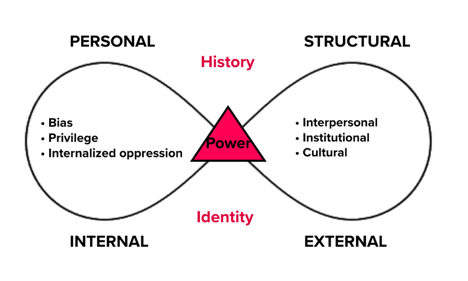

Understanding Power and Oppression as Systems

Systems of Power

Systems of power are the beliefs, practices, and cultural norms that reinforce white supremacy, patriarchy, and heteronormativity as the defining power structures in Canada.[19]

We are all part of these systems, whether we are conscious of it or not. We all either benefit from or are limited by these systems, and many of us experience both benefits and limitations, depending on our personal and social identities.

Systems of Oppression[20]

The term systems of oppression helps us better identify inequity by calling attention to historical and organized patterns of marginalization, abuse, and exploitation. In Canada, systems of oppression (like systemic racism) are woven into the very foundation of Canadian culture, society, and laws. Other examples of systems of oppression include but are not limited to sexism, heterosexism, ableism, classism, ageism, and anti-Semitism. Society’s institutions, such as government, education, health, and culture, all contribute to or reinforce the oppression of social groups that have been marginalized while elevating dominant social groups.[21]

There are levels of oppression that make it a system.[22] These levels are:

- personal

- interpersonal

- institutional

- cultural

“When we look at racism, sexism, classism, ableism, heterosexism, and other forms of oppression or “isms,” it may be difficult for us to see these issues as an interlocking system operating at the personal, interpersonal, institutional, and cultural levels.”[23]

This is at least partly because many of us only witness or hear about examples of these isms at the personal level (an individual tells a racist joke or makes a homophobic slur) or at the interpersonal level (a teacher expects lower academic achievement from their Black students, or a woman is passed over for a promotion in a non-traditional occupation). Broadening our understanding of these four levels of oppression can help us understand oppression as a system.[24]

Systems of Inequity

The Systems of Inequity Model

|

Reflect |

- What other examples of structural inequities have you seen or experienced?

- What types of oppression do you have control over, as an educator or student services professional?

Connect Personal and Structural Inequities

Thinking about systems of inequity helps us understand and internalize the continual interaction between personal (internal) and structural (external) oppressions. This self-perpetuating system must be interrupted at both the internal and external levels for lasting change to occur.

As potential change-makers, the importance of ongoing work to understand and heal our own internalized privilege or oppression is integral to our ability to analyze and dismantle systemic inequity.

The Systems of Inequity Model is important to everything you will learn in these modules. Reflecting on it will support your personal growth, as well as build your capacity to analyze inequity in policy, law, health, and institutions, in particular the education system.

Each module includes a reflection on personal identity as well as a reflection on structural inequities — which uses the Systems of Inequity Model. Looking at and connecting the big picture to your internal work and examining your own spheres of influence is critical.

In order to make change, we must hold both the collective and the individual responsible.

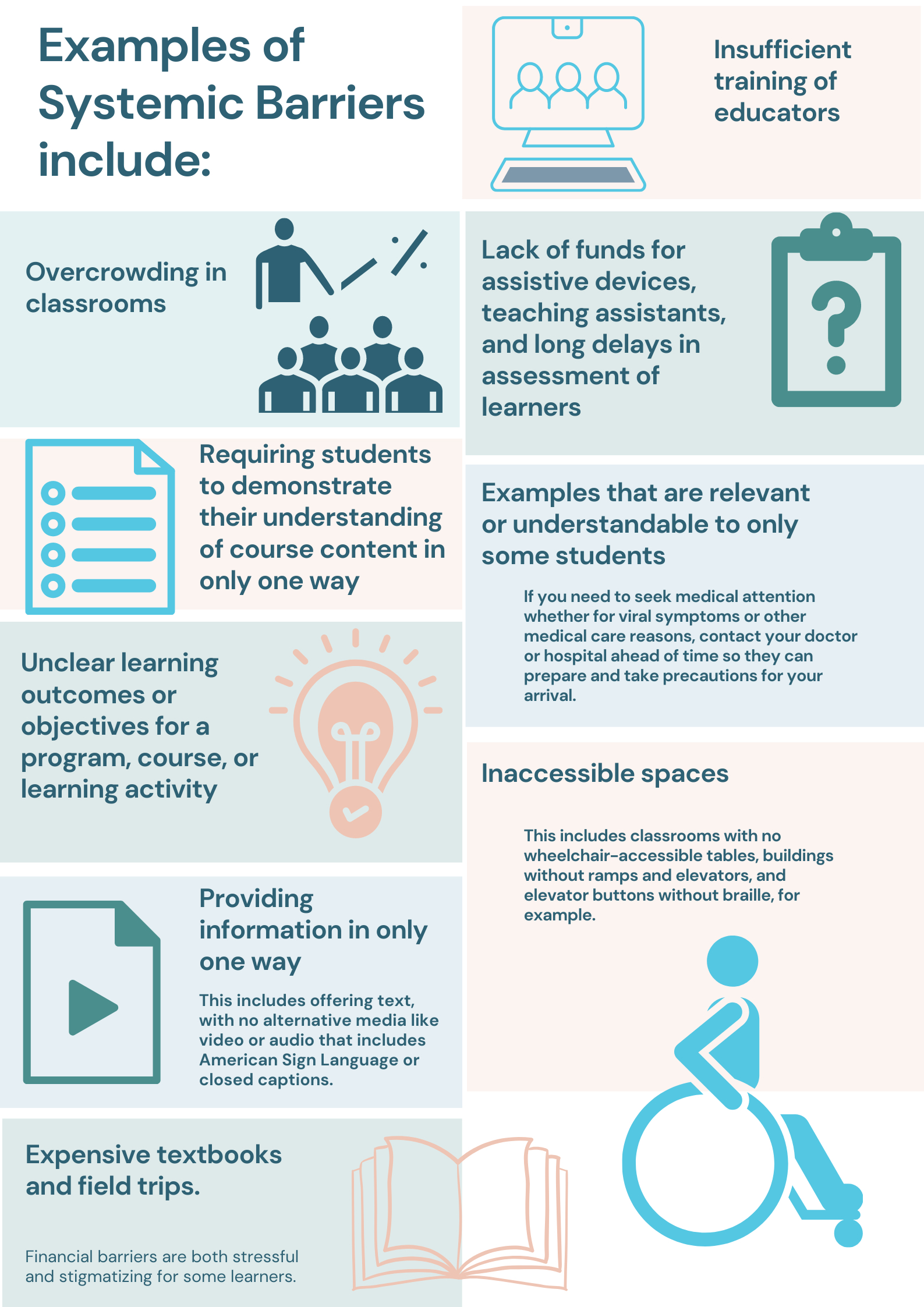

Systemic Barriers in the Education System

Systemic barriers to learning are created by the education system itself, as a result of policies, procedures, or practices that prevent individuals from having equitable access to services or resources so they can fully participate. These barriers are put in place intentionally and unintentionally, and can have severe negative impacts.

Tereigh Ewert: Going deeper to look at how education systems and institutions are oppressive.

Nik Basset: How the history of public education lays a foundation for oppression.

Systemic barriers disproportionately affect equity-seeking groups in Nova Scotia, including students of African descent, Indigenous students, students with disabilities, immigrant and international students, and 2SLGBTQ+ students.

Examples of systemic barriers include:

- Insufficient training of educators

- Overcrowding in classrooms

- Lack of funds for devices, teaching assistants, and long delays in assessment of learners

- Requiring students to demonstrate their understanding of course content in only one way

- Examples are relevant or understandable to only some students.

- If you need medical attention whether for viral symptoms or other medical care reasons, contact your doctor or hospital ahead of time so they can prepare and take precautions for your arrival.

- Unclear learning outcomes or objectives for a program, course or activity

- Inaccessible Spaces

- Providing information in only one way.

- This includes offering test, with no alternative media like video or audio that includes American Sign Language or closed captions.

- Expensive textbooks and field trips.

- Financial barriers are both stressful and stigmatizing for some learners.

“To create equitable learning environments, educators and staff must be aware of the barriers that affect student learning and educational opportunities, and they must proactively remove the barriers that are within their control.”[25]

Story: “Poverty is still that glass ceiling or glass door”

Ann Sylliboy, Post-Secondary Consultant with Mi’kmaw Kina’matnewey (MK), tells a story about what happens when a student tries to apply for university without a credit card.

MK is a unified team of chiefs, staff, parents, and educators who advocate on behalf of and represent the educational interests of Mi’kmaw communities and protect the educational and Mi’kmaw language rights of the Mi’kmaq people.

I had a call from a parent whose son was applying to a university, to a fairly competitive and highly sought-after program. But they needed a credit card to apply online, and they don’t have a credit card. I know these parents. They both work, but they’re just people that don’t believe in credit card debt. The parent or the community director did call the registrar, and said, you know, is this really the only way to process this application? We don’t have a credit card, and my son, who’s not 18 and just graduated out of high school doesn’t have a credit card. The registrar told the parent, well then you should, or you should try and borrow a credit card, kind of rudely.

I met with the school, and I said I’m not just here on behalf of Mi’kmaq people — I think I’m here on behalf of poor people. The elitist thinking behind ‘If you don’t have a credit card, you’re not welcome at our school’. The messaging to that student is, you know, if you are not of a certain “class”, that’s it for admissions.

We have lots of students that could be applying to lots of programs and have the potential and have something to offer to schools. And this gatekeeping sends the message that there is a certain level you need to have and if you do not have it then don’t even bother. That’s even before getting into university, right? That’s just admissions. I think the message is you don’t want poor people. You only want people that have good credit. And what does good credit mean, right?

I find there’s attention paid to Indigenous students; there’s attention paid to African Nova Scotian students; there’s attention paid to students with physical and learning disabilities, but there’s no real mention of poor students. Poverty is still that glass ceiling or glass door that hasn’t even been broached by universities.

I don’t think they were being racist, and I don’t think it was just Indigenous students, it was just this assumption that everybody should have a credit card. There are impoverished communities all over Nova Scotia and everybody says that post-secondary education is the way out of poverty. I don’t 100 percent agree, but I mostly agree, and there’s some intersections along the way.

If you’re poor, then, there’s kind of no hope. And you know what, even if I were to go finish high school, you know, am I going to go to university? How am I going to get in? And that one incident with the credit card kind of highlights it: “Right, yeah, you’re right. You’re not getting in.”

|

Reflect |

- What systemic barriers do you notice in your institution?

- What barriers do you have control over, as an educator or student services professional?

Systems of White Supremacy and White Privilege[26]

The New York Times reports that the term “white supremacy” was used fewer than 75 times in 2010, but nearly 700 times in 2020 alone (as of the article’s printing on Oct 17, 2020). Originally, white supremacy was the belief that white people are superior to Black, Indigenous, and people of colour and should therefore dominate them. White supremacy brings to mind extremist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazis, and Proud Boys[27].

Today, white supremacy is used to justify entrenched systemic, structural, environmental, and institutional racism and refers to a political and socio-economic system where white people enjoy structural advantages and rights that other racial and ethnic groups do not. Many white people are unaware that this system exists, which is one of its successes.

Peggy McIntosh’s influential article White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack[28] discusses the everydayness of unearned entitlements and advantages. White privilege includes powerful incentives for maintaining this privilege and its consequences, and powerful negative consequences for trying to interrupt or reduce its consequences.

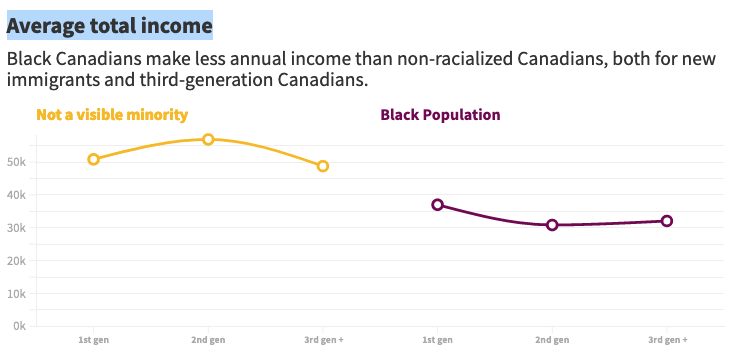

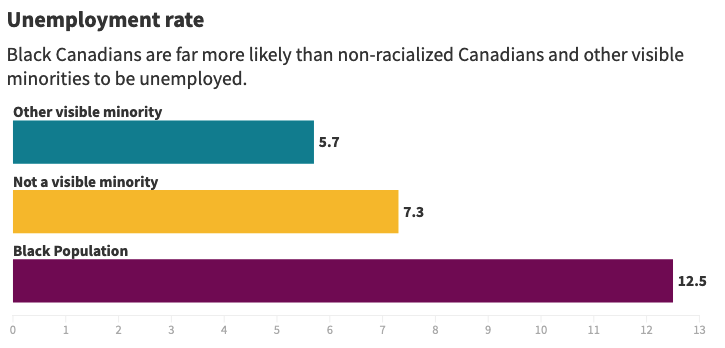

The racist and oppressive structures of white supremacy and the privileged people who uphold and benefit from them — intentionally or unintentionally — are responsible for:

- ongoing, disproportionate levels of poverty for Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC)

- poorer health, lower levels of education, and fewer job opportunities for BIPOC than for their white peers

- employment discrimination and lower earnings for BIPOC compared to their white peers

- poor living and working conditions, less access to health care, and an increased likelihood of being the victim of police violence for BIPOC

We’ll talk more about tangible, everyday examples of these oppressive structures in the Calling Out Racism module.

While it is possible for any person to experience low income and reduced opportunities, individual and systemic racism play a significant role in creating disadvantages and barriers for BIPOC.

Understanding and accepting white privilege is not an academic exercise. Our responsibility is to internally and externally work to dismantle the system of white supremacy in all its forms.

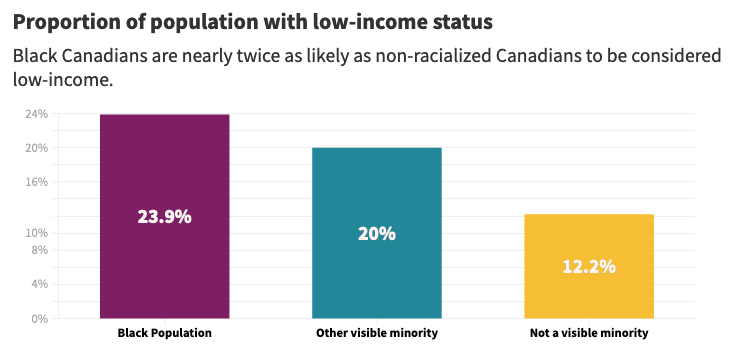

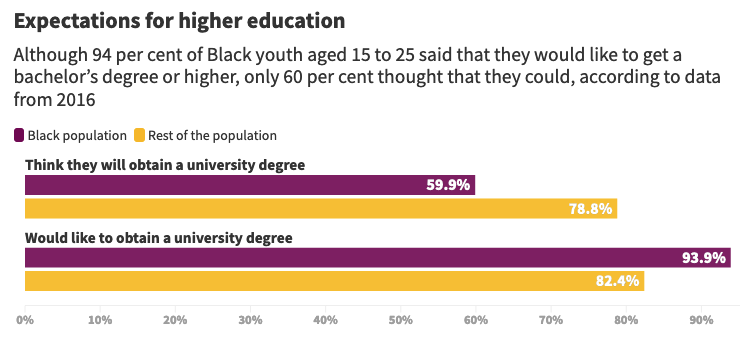

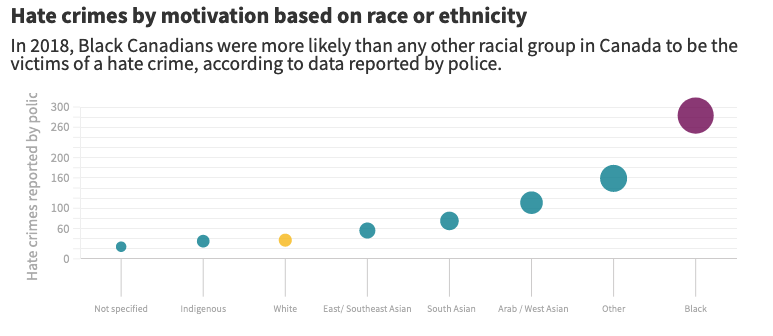

What does systemic racism look like in Canada?

Five charts that show what systemic racism looks like in Canada

By Graham Slaughter and Mahima Singh posted June 24, 2020 to CTV News.

Graph source: Slaughter, G. & Singh, M. (2020, June 4). Five charts that show what systemic racism looks like in Canada. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/five-charts-that-show-what-systemic-racism-looks-like-in-canada-1.4970352

Graph Source: Slaughter, G. & Singh, M. (2020, June 4). Five charts that show what systemic racism looks like in Canada. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/five-charts-that-show-what-systemic-racism-looks-like-in-canada-1.4970352

Graph Source: Slaughter, G. & Singh, M. (2020, June 4). Five charts that show what systemic racism looks like in Canada. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/five-charts-that-show-what-systemic-racism-looks-like-in-canada-1.4970352

|

Reflect |

Consider and complete the statements below

- In my view, the most important message is…

- I didn’t realize that…

- For me systemic racism means…

White Supremacy and the Education System

Achievement gap and opportunity gap are two of the most widely used terms in the educational research and policy world. Achievement gap serves as shorthand for widespread and persistent disparities in educational outcomes (i.e., standardized test scores) between Black and Indigenous students and their Asian and white peers; opportunity gap refers to inequities in resources (and thus opportunities).

Questions about achievement and opportunity gaps have grown louder in recent years. Educators, researchers, parents, and students alike are challenging this narrative by implying that it is students of colour and their families who are failing in school, rather than schools and school systems failing students.

Typically, the goal of conversations about these gaps is educational equity for all.

Historical narratives that decentralize whiteness

Jean-Blaise Samou: The gap between what institutions say and what they do.

Tereigh Ewert: Add and infuse historical narratives that decentralize whiteness.

|

Reflect |

- How do the Dominant Higher Education Structures Support White Supremacy?

Activity

Choose the article that resonates most with you, then answer the reflection questions.

1. Being Black on campus: Why students, staff, and faculty say universities are failing them

, posted on CBC News February 24, 2021. Students, staff, and faculty at some of Canada’s largest universities say they have experienced anti-Black racism on campus, and that they were targeted if they spoke out about their treatment, an investigation by The Fifth Estate has found.

2. Inequality Explained: The hidden gaps in Canada’s education system by Anastasia Rogova, Ashley Pullman, Cristina Blanco Iglesias, & Rachel Bryce posted January, 19 2016 to Open Canada. Written by students, this article explores how income inequality impacts educational attainment.

Despite Canada’s efforts to promote equal access to education, the experiences and outcomes of students differ greatly depending on their family incomes. The authors explore the educational opportunities of the top and bottom 10 per cent of students in the early childhood, primary, secondary, and postsecondary sectors. They illustrate how, in Canada, these groups are differentiated by much more than just income.[29]

|

Reflect |

- What does this story highlight for you?

- How do the dominant higher education structures support practices for the continuation of white supremacy?

Conclusion

The Systems of Inequity module built a foundation for your learning about social equity. You learned about some of the systems that shape daily life and life outcomes for people in Nova Scotia and Canada, including:

- Social systems

- Systems of power and oppression

- Systems of white supremacy and white privilege

- Education systems

- Connecting personal and structural inequities

You also learned how these systems can create and perpetuate or uncreate and stop social inequities and oppression. You were invited to reflect on these systems in relation to your own experiences as an educator or student services professional.

Learn More

Colour of Poverty – Colour of Change 2019 Fact Sheets by Colour of Poverty – Colour of Change (COP-COC) an Ontario based network.

Anti-Black racism in schools: Still a long way to go by Philip Moscovitch posted July 24, 2020 on the Halifax Examiner.

Me and White Supremacy by Layla F. Saad a new book published February 1, 2022 by Sourcebooks.

Inspiration Porn vs. Actual Inspiring People a blogpost posted February 3, 2020 by The Wheelchair Teen.

UN report slams Nova Scotia education system’s treatment of African Nova Scotians by Marieke Walsh posted September 25, 2017 on Global News.

Attribution

Unpacking Language: Key Terms adapted from University of British Columbia & Queen’s University. (n.d.). 2. Unpacking Language. In Module 1: Power, Privilege and Bias.[online curriculum]. Shared under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

White Supremacy and the Education System adapted from Hughes-Hassell, S., Rawson, C. H., & Hirsh, K. (2019). Module 14: (In)Equity in the Education System. In Hughes-Hassell, S., Rawson, C. H., & Hirsh, K. (Eds.), Project READY: Reimagining Equity & Access for Diverse Youth [online curriculum]. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Lumen Learning. (n.d.). What is sociology. In Introduction to Sociology. CC BY. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sociology/chapter/what-is-sociology/ ↵

- ibid. ↵

- Durkheim, Émile. 1964 [1895]. The Rules of Sociological Method, edited by J. Mueller, E. George and E. Caitlin. 8th ed. Translated by S. Solovay. New York: Free Press. ↵

- Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Functionalism. In Introduction to Sociology. CC BY. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sociology/chapter/theoretical-perspectives/ ↵

- Social Systems. (Date). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_system ↵

- Environment and Ecology. (n.d.). Systems thinking. http://environment-ecology.com/general-systems-theory/379-systems-thinking.html ↵

- The CARED Collective. (2020, September 28). Our Glossary. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/511bd4e0e4b0cecdc77b114b/t/60c79621d2b7b530aa639143/1623692835250/CARED+Glossary+Final+2020-converted-compressed.pdf ↵

- Adapted from Northwestern Searle Center for Advancing Learning and Teaching. (n.d.) Social Identities. https://www.northwestern.edu/searle/initiatives/diversity-equity-inclusion/social-identities.html#:~:text=%20Social%20Identities%20%201%20Race%20and%20Ethnicity.,relation%20to%20the%20lesbian%2C%20gay%2C%20bisexual%2C...%20More%20 ↵

- LearnRidge. (2021). Glossary. In LearnRidge's Supporting Survivors of Sexual Violence: A Nova Scotia Resource. [online curriculum]. https://nscs.learnridge.com/glossary/ ↵

- The CARED Collective. (2020, September 28). Our Glossary. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/511bd4e0e4b0cecdc77b114b/t/60c79621d2b7b530aa639143/1623692835250/CARED+Glossary+Final+2020-converted-compressed.pdf ↵

- LearnRidge. (2021). Glossary. In LearnRidge's Supporting Survivors of Sexual Violence: A Nova Scotia Resource. [online curriculum]. https://nscs.learnridge.com/glossary/ ↵

- Canadian Race Relations Foundation. (n.d.). CRFF Glossary of Terms. https://www.crrf-fcrr.ca/en/resources/glossary-a-terms-en-gb-1?letter=p&cc=p ↵

- Adapted from The CARED Collective. (2020, September 28). Our Glossary. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/511bd4e0e4b0cecdc77b114b/t/60c79621d2b7b530aa639143/1623692835250/CARED+Glossary+Final+2020-converted-compressed.pdf ↵

- ibid. ↵

- Canadian Race Relations Foundation. (n.d.). CRFF Glossary of Terms. https://www.crrf-fcrr.ca/en/resources/glossary-a-terms-en-gb-1?letter=p&cc=p ↵

- The CARED Collective. (2020, September 28). Our Glossary. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/511bd4e0e4b0cecdc77b114b/t/60c79621d2b7b530aa639143/1623692835250/CARED+Glossary+Final+2020-converted-compressed.pdf ↵

- LearnRidge. (2021). Glossary. In LearnRidge's Supporting Survivors of Sexual Violence: A Nova Scotia Resource. [online curriculum]. https://nscs.learnridge.com/glossary/ ↵

- LearnRidge. (2021). History - Slavery, Entrenched Racism, and Black Activism. In LearnRidge's Supporting Survivors of Sexual Violence: A Nova Scotia Resource.[online curriculum]. https://nscs.learnridge.com/topic/anshistory/ ↵

- Definition copied and adapted to reflect Canadian context. Source: The Centre for Law and Social Policy. (2019). Our Ground, Our Voices: Systems of Power and Young Women of Color. https://www.clasp.org/our-ground-our-voices-young-women-color ↵

- Paragraph defining Systems of Oppression copied and updated to reflect Canadian context. Source: Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. (n.d.). Social identities and systems of oppression. In Talking About Race. https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/social-identities-and-systems-oppression ↵

- ibid ↵

- Concepts and definition of levels adapted from: Pizaña, Dionardo. (2017, December 29). Understanding oppression and “isms” as a system. Michigan State University Extension.https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/understanding_oppression_and_isms_as_a_system ↵

- Pizaña, Dionardo. (2017, December 29). Understanding oppression and “isms” as a system. Michigan State University Extension.https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/understanding_oppression_and_isms_as_a_system ↵

- Paragraph copied and updated to reflect Canadian context. Source: Pizaña, Dionardo. (2017, December 29). Understanding oppression and “isms” as a system. Michigan State University Extension.https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/understanding_oppression_and_isms_as_a_system ↵

- Ontario's Universities Accessible Campus. (n.d.). Understanding barriers to accessibility: An educator’s perspective. https://accessiblecampus.ca/tools-resources/educators-tool-kit/understanding-barriers-to-accessibility-an-educators-perspective/ ↵

- Section on Systems of White Supremacy and White Privilege is copied and adapted from Racial Equity Tools to fit a Canadian audience. Source: Racial Equity Tools. (n.d.). Systems of white supremacy and white privilege. https://www.racialequitytools.org/resources/fundamentals/core-concepts/system-of-white-supremacy-and-white-privilege ↵

- Powell, M. (2020, October 17). 'White supremacy’ once meant David Duke and the Klan. Now it refers to much more. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/17/us/white-supremacy.html ↵

- MacIntosh, P. (1989).White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. The National Seed Project. https://nationalseedproject.org/Key-SEED-Texts/white-privilege-unpacking-the-invisible-knapsack ↵

- Rogova, A., Pullman, A., Blanco Iglesias, C., & Bryce, R. (2016, January 19). Inequality Explained: The hidden gaps in Canada’s education system. Open Canada. https://opencanada.org/inequality-explained-hidden-gaps-canadas-education-system/ ↵