4 Calling Out Racism: Anti-Black and Anti-Indigenous Racism

Learning Objectives

- Articulate an expanded awareness and understanding of concepts including racial discrimination, anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism, colonization, and decolonization.[1]

- Reflect on how your identity, power, and privilege as an educator or student support professional positions you to call out or call in racial discrimination.

- Relate the lasting impacts of colonialism and systemic racism to the lived experiences of students.

Introduction Video

|

Throughout the module, we use this icon to suggest times to reflect on a concept, your professional practice, or yourself. We hope these questions help spark your thinking in new and creative directions. |

Race on Campus

From Race on Campus (2:22) mid-article.

Reflecting on Identity

Reflecting on our identities and acknowledging how they manifest in our education practice is ongoing work. Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your own identities and how they relate to this module.

Consider your own personal learning about the topic. Where do you fall on the following continuum?

| I have not yet begun thinking about this |

I have started to learn more about this. |

I am actively thinking and learning about this. |

I am applying my new learningand remain committed to further reflection and growth. |

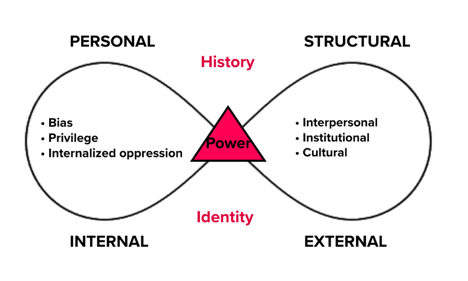

|---|---|---|---|

- In what ways does my social and geographical location influence my identity, knowledge, and accumulated wisdom? What knowledge am I missing?

- What privileges and power do I hold? In what ways do I exercise my power and privilege?

- Does my power and privilege show up in my work? If so, how?

- Am I aware of if/how my biases and privileges might take up space and silence others?

It’s important to realize that you do not have to be an expert on these topics to actively engage in self-reflection and conversations with students. Being an equity-centred educator requires regular and repeated reflection on the Eurocentric assumptions, knowledges, and ways of being that guide our thoughts and actions.

Being aware of which knowledges, experiences, and ways of being in the world are privileged in your discipline, classroom, and institution are a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is legitimate action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Unpacking Language: Key Terms

Words matter, and words can have multiple meanings.

In this section, you’ll engage with several important words and ideas related to power, privilege, and bias. We will only skim the surface of these important, complex, and deep-seated issues.

The purpose of this section is to establish a shared understanding and vocabulary to build on in future modules. This work is essential but is also sometimes uncomfortable. This should not deter us from doing it.

As a staff or faculty member, recognizing and addressing the meanings of these words in your planning and reflection is important. The more clearly a term is articulated, the more likely you are to develop the knowledge and skills to use it. You will also feel more comfortable talking about and using these words in your teaching and interaction with students.

Write

Take a couple of minutes to jot down your understanding of the following key terms (don’t worry about getting it right or perfect; the idea is to respond quickly):

- race

- racism

- racialization

- systemic racism

- colonization

- decolonization

- white supremacy

Review

race: Significant genetic studies conducted by physical anthropologists since the 1970s have revealed that biologically distinct human races do not exist. Certainly, humans vary in terms of physical and genetic characteristics such as skin color, hair texture, and eye shape, but those variations cannot be used as criteria to biologically classify racial groups with scientific accuracy.[2]

Three important concepts link to this fact:

- Race is a social construct, and not an actual biological fact

- Race designations have changed over time. Some groups considered white in Canada today were considered non-white in previous eras (for example, Irish, Italian, and Jewish people)

- The way racial categorizations are enforced (the shape of racism) has changed over time.

racism: Racism stems from the belief, either conscious or unconscious, that one race is better than another (or than all others). This belief can result in acts of racism, such as racial discrimination at work, school, or in a health care setting. Although racism can happen between individuals, it also takes place on a systemic and institutional level. Racism is systemic, structural, institutional, intentional, and a layered approach to dehumanize people.

racialization: Racialization describes the processes by which a group of people is defined by their race. Put very simply, racializing people categorizes them according to their perceived race and imposes racial character on that group as a whole. This racial meaning is then attributed to people’s identity as they relate to social structures and institutional systems, including housing, health care, employment, and education. These stereotypes, biases, and prejudices are socially constructed and have no scientific or biological basis. Typically, a subordinate or oppressed group is racialized by a dominant group to preserve the interests of that group.

systemic racism: Racism that consists of policies and practices, entrenched in established institutions, that result in the exclusion or advancement of specific groups of people. It manifests itself in two ways: (1) institutional racism: racial discrimination that derives from individuals carrying out the dictates of others who are prejudiced or of a prejudiced society; (2) structural racism: inequalities rooted in the system-wide operation of a society that excludes substantial numbers of members of particular groups from significant participation in major social institutions.[3]

white supremacy: white supremacy is the racist belief that white people are superior to those of all other races and should therefore dominate them. White supremacy perpetuates and maintains social, political, historical, and institutional domination by white people. Historically, white supremacy justified the Transatlantic Slave Trade and colonization.[4]

Today, white supremacy is used to justify entrenched systemic and institutional racism. Like racism in general, white people may not realize or acknowledge that they participate in and benefit from white supremacy.

|

Reflect |

- Which terms did you feel most confident defining? Which ones felt more difficult? Why do you think this is?

- How has your understanding of these terms changed over time?

This brief video from Vox to review the historical evolution of the term “race”. The myth of race, debunked in 3 minutes.

|

Reflect |

- In my view, the most important message is…

- I didn’t realize that…

- For me, race means…

Racism at Every Level of Society

Racism Lives Here Too

Watch

A 2-part series, Racism Lives Here Too, from APTN News.

- ‘All my ancestors are survivors’: Racism and the relationship between Black and Mi’kmaw Peoples in Nova Scotia by Trina Roache posted November 06, 2020 on APTN National News.

- ‘Nova Scotia is the deep south of Canada’: A Look at racism from people who live it by Trina Roache posted November 13, 2020 on APTN National News.

Treaty Education Nova Scotia Video

This Treaty Education Nova Scotia Video describes who are the Mi’kmaq, why are treaties important, what happened to the treaty relationship and how to reconcile moving forward.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=8h5QhkZzrbY

Canada. it’s time for Land Back

The Breach is an independent media outlet in Canada that produces critical journalism to help map a just, viable future. Lawyer and professor Pam Palmater argues that symbolic gestures won’t amount to justice.

Study looks at prevalence of racism in Canada – segment from December 9, 2019 edition of The National on CBC.

|

Reflect |

- What is your biggest takeaway from these videos?

- What surprised you?

- What does the phrase “We are all treaty people” mean to you?

Anti-Black and Anti-Indigenous Racism in Nova Scotia

Anti-Black Racism

Child and Youth Development

- Systemic bias resulting in worse educational outcomes for Black students.

Job Opportunities and Income Supports

- Reduce likelihood of Black Canadians succeeding in the job hiring process.

- Impaired career progression and lower levels of integration for Black employees.

Health and Community Services

- Inferior access to healthcare (physical and mental) for the Black population versus other groups.

Policing and the Justice System

- Racial profiling of Black communities and biased outcomes in police interactions.

Anti-Indigenous Racism

Child and Youth Development

- One of the most notorious forms of racism at the institutional level was the residential school system, which represented the attempted assimilation of indigenous children.

Job Opportunities and Income Supports

- Difficulty connected to labour market opportunities. Some of the barriers include systemic racism and discriminatory hiring practices.

- In Nova Scotia, some of the highest child poverty rates are in Mi’kmaw communities.

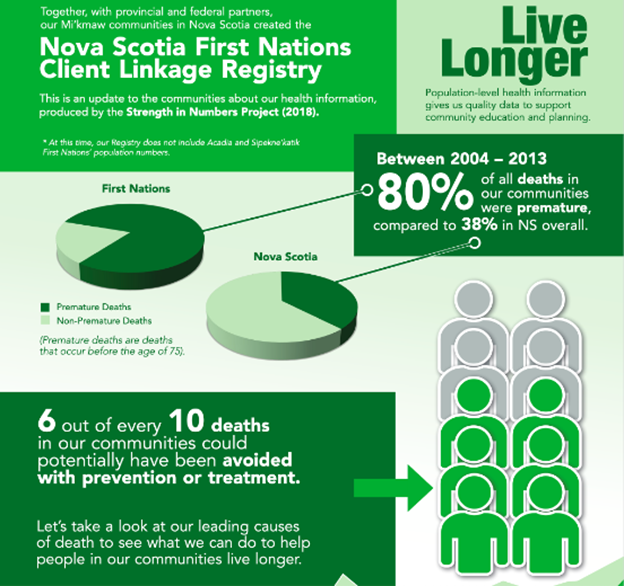

Health and Community Services

- Inferior access to health care (physical and mental) leading to premature and preventable deaths.

Police and the Justice System

- Overwhelming over representation in police involved deaths in Canada and disproportionate incarceration.

How do we know that systemic racism is real and rampant in Nova Scotia?

Introduction

Systemic racism is a corrosive and widespread problem in our society. In recent years, many incidents and practices across the province demonstrate this, including violence against Indigenous people[5] asserting their treaty rights; racist slurs [6]used on a popular transit app; and police street checks [7]that target Black people six times more often than white people in Halifax. These are only a few examples of racism in Nova Scotia.

We all need to do a better job of confronting it — in our work, in our neighborhoods, and in ourselves. As faculty and staff, we need to confront racism in our work with students, to build equity and belonging for everyone.

This section gives more concrete examples of the impacts of systemic racism.

1. Education

Residential school system

One of the most notorious forms of racism at the institutional level was the residential school system, which represented the attempted assimilation of Indigenous children.

In 1880, the first residential school was established in Canada, located off-reserve, funded by the federal government, and run predominantly by Catholic and Anglican churches. Until the 1950s, First Nations (and some Inuit and Métis) children between the ages of five and 16 were forced to attend these schools — many miles and for many months or years — away from their families and cultural traditions. Parents did not approve of the aggressive assimilation practices undertaken by school administrators but had no recourse or authority to remove their children from these institutions.[8]

In May 2021, the news broke that preliminary findings from a survey of the grounds at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School uncovered the remains of 215 children buried at the site.[9]

Read

The Where are the children? Healing the impacts of Residential Schools by the Legacy of Hope Foundation.

The Memorial Map from the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation represents the location of residential schools, and the home communities of the students who never returned home from school.

Listen

Dennis Saddleman on CBC Radio’s The Current performing his poem, Monster about the residential school he was forced to attend as a child.

In 2021,

THOUSANDS

of graves have been

uncovered on or near the

sites of former Indian

Residential Schools in

Canada.

African Nova Scotian learners[10]

The opportunity gap between African Nova Scotian learners and white learners continues to expand, and along with it the opportunity gap. Unlike their white counterparts, many African Nova Scotian learners do not have access to the same resources because a large proportion of African Nova Scotian parents continue to endure poverty and low incomes, and systemic racism.

Equally, a long history of racism and poverty robbed many African Nova Scotian parents and grandparents of access to formal education. In the early 19th century, the provincial governments of Ontario and Nova Scotia created legally segregated common schools, also known as public schools. Amendments in 1884 stipulated that Black children could not be excluded from attending schools where they lived; racial segregation continued in some areas with high concentrations of Black residents, such as Halifax. The original provisions of racial segregation in education remained law in Nova Scotia until 1950. The legacy of systemic racism shows up in subsequent generations.[11]

The education system in Nova Scotia continues to fail African Nova Scotian learners. The BLAC Report on Education, written in 1994, made many recommendations to redress inequities in the education system.[12] To date, some of those recommendations have not been implemented.

There is very little in the system that reflects African Nova Scotian history, perseverance, accomplishments, contributions, culture, or resilience. Hundreds of African Nova Scotian learners have been stereotyped as unruly and learning-capacity impaired, often streamed into non-academic programs unsuitable for college and university prep and Individual Program Plans (IPPs). “The 2016 Individual Program Plan (IPP) Review found that African Nova Scotian students were 1.5 times more likely to have an IPP in at least one subject or programming area … Indigenous students were 1.4 times more likely to have an IPP than non-Indigenous students.[13] African Nova Scotian learners are also suspended from school at higher rates than other students.[14]

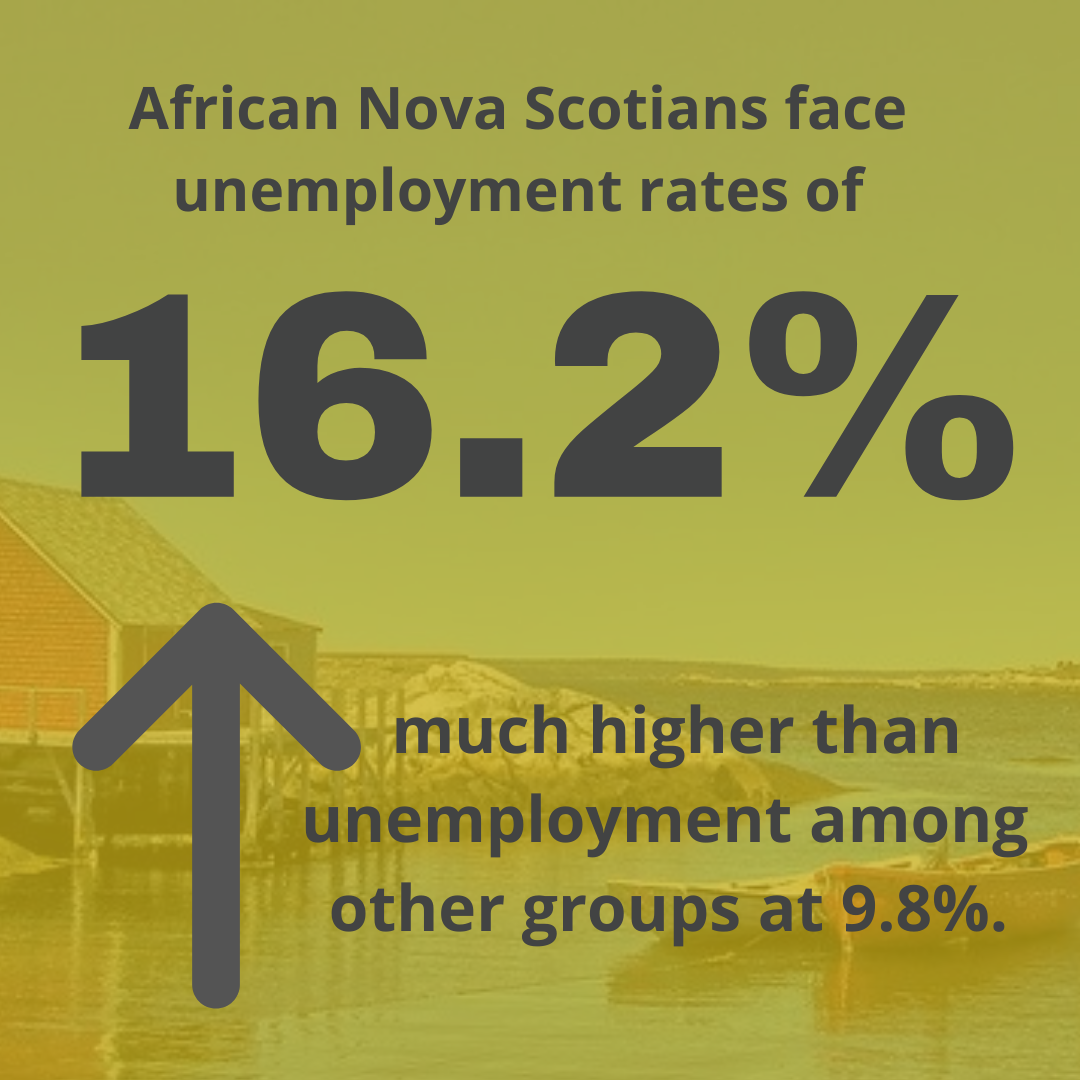

2. Employment

According to the OneNS Dashboard, First Nations and African Nova Scotians as general population groups have traditionally been economically disadvantaged in Canada and have faced systemic difficulties connecting to labour markets. Some of the barriers to successful labour market attachment include systemic, structural, and institutional racism and discriminatory hiring practices.[15]

It’s not a matter of Black Nova Scotians giving up. Statistics Canada data shows that a slightly higher percentage of African Nova Scotians (10%) are actively trying to find a job, compared to 6% for whites.[16] These numbers point at the ongoing and systemic racism in Nova Scotia that stops African Nova Scotians from finding good jobs and working their way out of poverty.

The stories below shine a light on systemic racism in Canada.

In their words: Canadians’ experiences of racism by Brooklyn Neustaeter posted June 9, 2020 to CTV News. The story includes an interview with George Swaniker, a NSCC faculty member, about his experience finding employment in NS.

5 things to know about the dispute over Nova Scotia’s Indigenous lobster fishery By Michael MacDonald posted October 21, 2020 on Global News. This story is about Nova Scotia’s Mi’kmaw communities trying to carry out their right to a moderate livelihood fishery. They faced violence from Nova Scotians and the police.

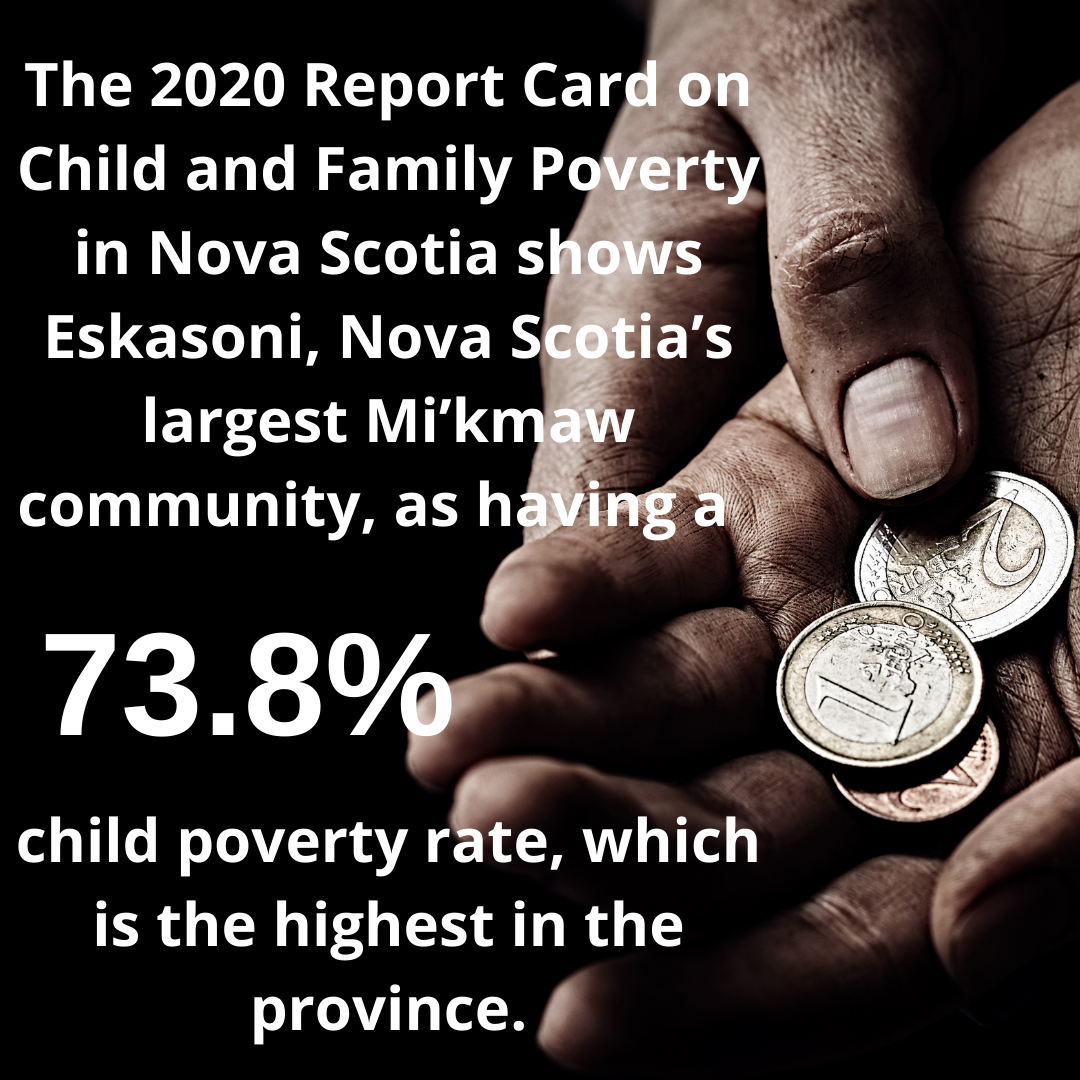

3. Poverty[17]

Census data from 2016, from Statistics Canada, showed poverty to be more rampant in Nova Scotia than any other province, with 17.2 percent of the provincial population considered low income. As shocking as this number is, it pales in comparison to the poverty rate of 32.1 percent among African Nova Scotians, who face poverty rates of twice the number experienced by whites.[18]

For African Nova Scotian youth 18 to 24, the poverty rate is 50.2 percent; 39.6 percent of African Nova Scotian children up to 17-years old live in poverty. The 2020 Report Card on Child and Family Poverty in Nova Scotia shows Eskasoni, Nova Scotia’s largest Mi’kmaw community, as having a 73.8 percent child poverty rate, which is the highest in the province.[19]

4. Environmental Racism

Environmental racism is a form of systemic racism whereby communities of colour are disproportionately burdened with health hazards through policies and practices that force them to live in proximity to sources of toxic waste such as sewage works, mines, landfills, power stations, major roads and emitters of airborne particulate matter. As a result, these communities suffer greater rates of health problems.[20]

Environmental devastation is most often felt by people who have been marginalized; in Canada, that means Indigenous, Blacks, and other people of colour. The pattern has, and continues, to repeat itself. It is environmental racism. It’s blatant and systemic.

One of the most egregious cases in the country is on the Pictou Landing First Nation in Nova Scotia. Here, a pulp and paper mill dumped toxic effluent directly into Boat Harbour, on the reserve, for over 50 years. It’s been devastating for the community. The Northern Pulp mill in Boat Harbour, NS, had to shut down in January 2020, amid concerns about pollution and environmental racism after decades of effluent treatment.[21]

Another example is Lincolnville, a Black community within the Town of Shelburne, NS, where residents are worried about contamination from a nearby landfill. They want authorities to investigate their health-related fears and to provide access to town water.[22]

5. Police Violence

Both Indigenous and Black people are overwhelmingly over represented in police-involved deaths in Canada. Between 2007 and 2017, Indigenous peoples represented 1/3 of people shot to death by RCMP police officers.[23] The Ontario Human Rights Commission found that a Black person in Toronto was more than 20 times more likely to be shot and killed by the police compared to a white person.[24]

Listen

A look at anti-black racism in Canada (9:59) CBC News host Carole MacNeil speaks to Robyn Maynard, author of Policing Black Lives: State violence in Canada from slavery to the present, about anti-Black racism in Canada.

6. Surveillance: Street Checks

Street checks are also known as carding. They have allowed police officers to document information about a person they believe could be of interest to a future investigation, and record details such as their ethnicity, gender, age, and location. Black people are six times more likely than white people in Halifax to be carded. In October 2019, after many years of community activism, it was announced that the practice of street checks is now banned. Although this is a positive step, there is still lots of work to be done in addressing systemic racism within law enforcement.[25]

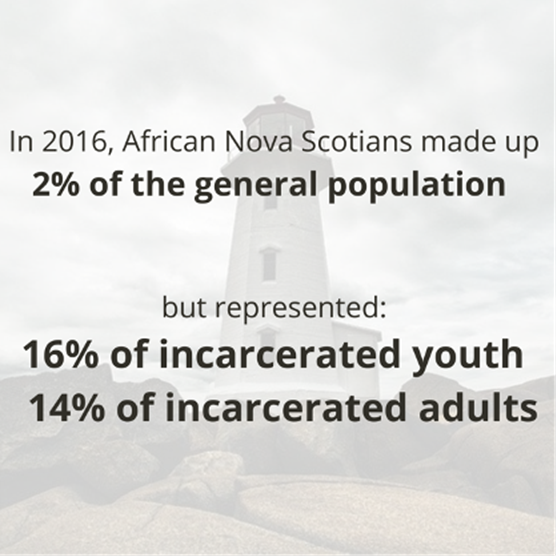

7. Criminal Justice: Disproportionate Incarceration Rate

There are few Canadian statistics on issues affecting Black people. It was only in 2014 that a report was issued about the conditions Black inmates endure while in federal correctional facilities. Black people are now the fastest-growing group of incarcerated people in Canada, and rates of incarceration for Black women are increasing steeply.[26]

The disproportionate incarceration of African Nova Scotians and Indigenous people in this province is clear: 2014-15 numbers from the Nova Scotia Department of Justice, show African Nova Scotians made up 2 percent of the general population in Nova Scotia but 16 percent of incarcerated youth and 14 percent of incarcerated adults; Indigenous people made up 5.7 percent of the general population but 12 percent of incarcerated youth and 7 percent of incarcerated adults.[27]

Indigenous offenders are more likely to receive jail sentences if convicted of a crime and are currently the most over-represented group in the Canadian criminal justice system.

8. Health Care

Racism within Canada’s health care system

Racism within Canada’s health care system is a significant contributor to lower health outcomes for Black, Indigenous, Métis, and Inuit people. Structural racism exists in policies and practices throughout the Canadian health care system that are expressed through longer wait times, denial of access to services and resources, fewer referrals, and disrespectful treatment.[28]

Joyce Echaquan’s death

https://globalnews.ca/video/embed/7370087/

Joyce Echaquan’s death and the abuse she faced in her last moments have put a focus on systemic racism. Her life could have been saved but wasn’t.[29]

Deaths in Mi’kmaw communities in Nova Scotia

In Nova Scotia, 80 percent of all deaths in Mi’kmaw communities are premature (versus 38 percent in the general population), and 60 percent of deaths are avoidable with prevention or treatment.

Anti-black racism in health care system

According to Barb Hamilton-Hinch, assistant professor at the school of health and human performance at Dalhousie University, access to health care can be a challenge for Nova Scotians of African descent.[30]

Read: How anti-Black racism affects the health of Nova Scotians of African descent by Nebal Snan posted June 6, 2020 in The Chronicle Herald.

Introduction to Decolonization

One of the core goals of this curriculum is unsettling our ways of thinking, just as a primary aim of teaching and learning is to challenge ourselves to embrace different frames of reference and ways of knowing. This section is a short introduction to this complex and ongoing journey.

In teaching and learning, to engage in decolonization is to engage in effective practice that:

- Disrupts traditional dichotomous thinking which keeps us entrenched in us/them, white/other, oppressed/oppressor binaries

- Makes us aware of how we hear and interpret each other’s narratives

- Is mindful of whose voices are and continue to be privileged

- Makes connections between the global and the local

|

Reflect |

- When you hear the word decolonization, what words, phrases, and ideas come to mind?

- How do you define decolonization within your practice?

Defining Terms

Colonization can be defined as some form of invasion, dispossession, and subjugation of a people. The invasion need not be military; it can begin, or continue, as geographical intrusion in the form of agricultural, urban, or industrial encroachments. The result is the dispossession of vast lands from the original inhabitants and is often legalized after the fact. The long-term result of such massive dispossession is institutionalized inequity. The colonizer/colonized relationship is, by nature, an unequal one that benefits the colonizer at the expense of the colonized.[31]

Decolonization may be defined as active resistance against colonial powers, and a shifting of power towards political, economic, educational, and cultural independence and power that originate from a colonized nation’s own Indigenous culture. This process occurs politically and applies to personal, societal and cultural, political, agricultural, and educational deconstruction of colonial oppression.[32]

- “Decolonization doesn’t have a synonym; it is not a substitute for ‘human rights’ or ‘social justice’, though undoubtedly, they are connected in various ways”.[33]

- “Decolonization demands an Indigenous framework and a centering of Indigenous land, Indigenous sovereignty, and Indigenous ways of thinking.”[34]

- “Decolonization is a goal, but it is not an endpoint…the struggle for decolonization is a journey that is never finished, and, on this journey, uncertainty is not to be feared.” [35]

Decolonization Learning Journey

Call to Action

Review the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action

and/or

The Spirit Bear’s Guide to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Calls to Action

This booklet is written by Spirit Bear as a youth-friendly guide to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) published by the First Nations Child & Family Caring Society of Canada.

Choose three Calls to Action that either relate to your discipline or that you can create links and interdisciplinary connections.

|

Reflect |

- What are two practical examples of how you would enact your chosen Calls to Action in your life and professional practice?

Read

Two-Eyed Seeing – Elder Albert Marshall’s guiding principle for inter-cultural collaboration [PDF]. Originally shared at the NS: Climate Change, Drawdown & the Human Prospect: A Retreat for Empowering our Climate Future for Rural Communities held at Thinkers Lodge in Pugwash N.S., September 28 – October 1 2017. This summary presents a comprehensive view of the two-eyed seeing approach to understanding Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledges.[36]

|

Reflect |

- After you have read Elder Albert Marshall’s guiding principle, reflect on the ways in which this approach appreciates Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives and sees them as necessary for personal advancement and development.

Aboriginal Worldviews and Perspectives in the Classroom: Moving Forward

|

Reflect |

- Although it was created for the K–12 system, think about what you can learn from this video about the need for Indigenization for all students.

Student Perspectives on Decolonization

In this video, you will hear from students at Queen’s University on the topic of decolonization. Take note of their diverse understandings of decolonization and how important it is to their learning.

What Does Indigenizing the Curriculum Mean?

This is an interview with Jo-ann Archibald, professor and the director of Native Indian Teacher Education Program (NITEP) at the Department of Educational Studies (EDST), as well as the associate dean for Indigenous Education at the Faculty of Education at UBC. She talks about what ‘Indigenizing the curriculum’ means and how it can be practiced.

|

Reflect |

- What perspectives in the videos most resonated with you? Why?

- What elements from the videos do you see in your own practice?

- What new ideas have the videos and your reflection on them sparked?

Read

Pete, Schneider, and O’Reilly’s (2013) article Decolonizing Our Practice, Indigenizing Our Teaching [PDF] for a deeper exploration of what these terms entail from the perspective of three female (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) academics.[37]

|

Reflect |

- Use the subheadings in their article to document your own position and perception of these topics, constructs, and issues as they relate to your institution, your students, and your colleagues.

- If possible, engage one or two colleagues in a conversation similar to the authors’ conversation.

The journey to Indigenize your practice fosters self-development. Whether you are an Indigenous or non-Indigenous person, this journey challenges your insights into your own culture and background, privileges, or oppressions that have affected your life. You will question the pervasive dominance of Western ways of knowing, pedagogies, and practices, and make space for including Indigenous ways of being that can benefit all learners.

If you want to learn more, a comprehensive curriculum is contained in the open textbook Pulling Together: A Guide for Curriculum Developers by Asma-na-hi Antoine; Rachel Mason; Roberta Mason; Sophia Palahicky; and Carmen Rodriguez de France published by BCCampus.

Calling Out Racial Discrimination

In light of the killing of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis and the global Black Lives Matter movement, universities and colleges everywhere have been quick to put out anti-racist statements; some have promised to recontextualize their historical links to slavery and colonization. In some places, statues have been removed and lecture theatres renamed.

But that is the easy bit. The real question is whether post secondary institutions are effective in combating the racism on their campuses. Do students feel comfortable reporting racism? What actually happens when you report racism to senior management? And how effective are the systems in place?

Antiracist education is good for everyone… It is good for the teacher, it is good for the learner, it is good for the administrator, it is good for the policy maker, because how we come to understand our world is powerfully connected to how we make sense of our existence in society.

Dr. George S. Dei[38]

In this section, you’ll learn about how your identity, power, and privilege as an educator or student support professional, positions you to call out racial discrimination. In this curriculum, we’ve already covered some important ideas about personal and social identities and how they position us in relation to our students, our professional practice, and our institutions.

What does it mean to “call out” racism?

Your approach to calling out racism will depend on how you are positioned and how personally safe you feel in any given situation. Remember that you are not obligated to speak up or take action if you feel unsafe, threatened, or at risk of harm. You can also seek support from others to speak up and report. What resources are available at your institution? Is there an anti-racism policy? Is there an equity office?

Sometimes, especially if you are one of only a few racialized people in your workplace or classroom, non-racialized people may turn to you for guidance. Although the intention might be positive, this approach can place most if not all responsibility for change on the backs of people who are already dealing with discrimination, microaggressions, and institutional racism. If you identify as a member of a racialized or oppressed group, it is not your responsibility to educate your colleagues or be their barometer for acceptable discourse of behaviour. How much you choose to participate in educating your colleagues is up to you.

The first step in preparing to talk about and call out racial discrimination when you see it, hear it, or experience it, is to learn about the history and lived experiences of racialized communities in Nova Scotia and Canada.

What does it mean to “call in” racism?[39]

While call outs can be important ways to speak truth to power and call racist people to account, call-out culture is also criticized. Call outs can be performative and a way to signal virtue that is more interested in self-aggrandisement than in achieving real change, especially on social media.

The concept of calling in seeks to refocus challenges to racism by talking to the person privately and aiming for change, rather than shame.

How do you do it? Actively decide if you will call out or call-in racism.

Calling out is useful when you need to let someone know when their behaviour is unacceptable, or when it must be interrupted to avoid causing more harm. This is also a signal to the wider community.

Calling in is useful if you want to engage someone in a deeper discussion, understanding and reflection. It involves listening as well as feedback in a two-way conversation.

Here are a few other ideas to get you started thinking about creating change at the institutional and personal levels.

Creating Change on an Institutional Level

-

Review Organizational Culture

- Review policies, practices, and decision-making for systemic racial discrimination

- Review organizational culture such as patterns of communication, interpersonal relations, and social networks

- Collect and analyze numerical data to identify areas of systemic discrimination

Building Reconciliation Forum, UVic

-

Create an Anti-Racism Strategy

An anti-racism strategy is a common approach that acknowledges and pro-actively seeks to address and prevent racism and racial discrimination.

A strategy could include:

- An anti-racism/discrimination vision statement and policy

- Monitoring and data collection

- Identifying and implementing strategies

Creating Change on Personal Level

- Recognize your own privileges

- Listen more than you speak

- Educate yourself constantly (especially about historical and ongoing colonization and cultural genocide)

- Question and resist stereotypes (Refer to Module 9- Navigating Difficult Conversations)

- Learn about the history and current day realities of African Nova Scotians

- Tour the Black Cultural Centre, Africville Museum, and Birchtown Museum

- Participate in a Stop the Violence Walk

- Experience the Nova Scotia Mass Choir

- Educate yourself on the Restorative Inquiry (Home for Coloured Children)

- Visit an historic Black community

- Attend a church service

- Visit Pier 21

- Learn about the history and current day realities of Mi’kmaw people

- Read and promote the TRC Calls to Action

- Experience a Mi’kmaw Powwow

- Visit Millbrook Cultural and Heritage Centre

- Learn about treaties

- Invite first voice speakers to your spaces and value their time

- Explore and evaluate anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism resources and strategies for your practice.

- Take the University of Alberta’s course Indigenous Canada, a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) from the Faculty of Native Studies that explores Indigenous histories and contemporary issues in Canada.

Reflecting on Systems

Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your institution as a system and how it relates to this module. Think about the written and unwritten rules, policies, procedures, practices, and traditions that define your institution. Reflect on and write a few lines answering these questions:

- Who is welcomed and can fully participate?

- Who may be excluded, discriminated against, or denied full participation?

- Whose norms, values, and perspectives does the institution consider to be normal or legitimate? Whose does it silence, marginalize, or delegitimize?

- Who inhabits positions of power within the institution?

- Whose experiences, norms, values, and perspectives influence an institution’s laws, policies, and systems of evaluation?

- Whose interests does the institution protect?

Systems of Inequity

Thank you for taking the time to reflect on your own institution in relation to this module. Being aware of the policies, procedures, practices, and traditions and how they intentionally or unintentionally privilege some groups over others is a critical first step to making education equitable. (Link to Systems of Inequity). The next step is real action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Conclusion

Summary

To work effectively toward racial equity across systems and organizations, we need to build a firm foundation. In this module, we developed a shared understanding of concepts central to racial equity work.

You learned about:

- Anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism

- Colonization and decolonization

- How your identity, power, and privilege as an educator positions you to call out, or call in, racial discrimination

- How the lasting impacts of colonialism and systemic racism connect to the lived experiences of students

Learn More

Watch:

In their words: Canadians’ experiences of racism by Brooklyn Neustaeter, CTV News posted June 8, 2020 (1:18:27)

A’se’k – The Other Room (Boat Harbour) YouTube Video posted by Barrie Bernard (18:48)

Megan Ming Francis: Let’s get to the root of racial injustice TEDX (19:37)

Baratunde Thurston: How to Deconstruct Racism, One Headline at a Time, TED (16:50)

The Little Black School House (rental, $3.99)

Read:

Additional Resources to Support Your Decolonization Learning Journey by Community Sector Council of Nova Scotia.

The Stories We Tell: Land Acknowledgements & Indigenous Sovereignty posted October 9, 2020 to the Center for Story-based Strategy.

Anti-Racist Video Pedagogy Project. The Anti-Racist Video Pedagogy Project is a sustainable video repository of anti-racist materials at Concordia University.

Aboriginal Social Work Education in Canada: Decolonizing Pedagogy for the Seventh Generation by Raven Sinclair in First Peoples Child & Family Review, 1(1), 49-62.

For definitions of additional terms related to race & racism, check out the Racial Equity Tools Glossary

Anti-Black Racism Social Equity Action Card on Centennial College Libraries, Teaching & Learning in Higher Education Guide.

In 2010, the Taskforce on Anti-Racism at Ryerson University released a report that examined systemic racial issues and barriers on campus: Final Report of the Taskforce on Anti-Racism at Ryerson.

Understanding how racism becomes systemic by Colleen Sheppard, Tamara Thermitus, & Derek J. Jones, Centre for Human Rights & Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) at McGill University.

Opinion: Hiring a Black leader? Learn from my experience and treat it like it matters by Ivan Joseph, August 3, 2020 a contributed piece in The Globe and Mail.

NSCAD: The Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery website

How to Be an Antiracist a 2019 book by Ibram X. Kendi published by One World.

White Fragility a 2016 book by Robin DiAngelo published by Random House.

So, You Want to Talk About Race a 2018 book by Ijeoma Oluo published by Seal Press.

Policing Black Lives a 2017 book by Robyn Maynard published by Fernwood press.

The Skin We’re In a 2020 book by Desmond Cole published by Penguin Random House Canada.

Listen:

When should we call something or someone “racist?” The NPR podcast Code Switch explored this question.

Read: We Asked, You Answered by Leah Donnella, posted January 26, 2018 to NPR From Our Listeners.

Explore:

Indian Residential School Survivors Society website

The Legacy of Hope Foundation website

The Native Women’s Association of Canada website

First Nations Child & Family Caring Society website

Do:

Keep track of how the Canadian state is doing on the 94 Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Read:

Delivering on Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action on the Government of Canada’s Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada website.

Write to your MP to pressure for follow through on all 94.

Beyond 94. In March 2018, CBC News launched Beyond 94, a website that monitors progress on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action.

Attribution

Unpacking Language: Key Terms paragraphs adapted from University of British Columbia & Queen’s University. (n.d.). 2. Unpacking Language.

In University of British Columbia & Queen’s University’s Module 1: Power, Privilege and Bias. [online curriculum]. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Adapted from Queens University. (n.d.) Power, Privilege & Bias. https://healthsci.queensu.ca/sites/opdes/files/modules/EDI/power-privilege-bias/#/ ↵

- Brown, N., de Gonzalez, L. T., & McIlwraith, T. (2017). Race and Ethnicity in Cultural Anthropology. Lumen learning. CC BY-NC-SA. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-pima-ant112/chapter/chapter-5-race-and-ethnicity/ ↵

- Henry, F., & Tator, C. (2006). The colour of democracy: Racism in Canadian society. 3rd Ed. (p. 352). Toronto, ON: Nelson. ↵

- White Supremacy. (2022, February 19). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_supremacy ↵

- Star Staff. (2020, October 22). The legal rights of Mi’kmaq fishers in Nova Scotia and the violence they face. Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/podcasts/thismatters/2020/10/22/the-legal-rights-of-mikmaq-fishers-in-nova-scotia-and-the-violence-they-face.html ↵

- Burke, D. (2021, February 3). Moovit transit app blasted after racist slur used to identify historic N.S. Black community. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/racism-moovit-app-preston-public-transit-1.5898970 ↵

- CBC News. (2019, March 27.). Black people in Halifax 6 times more likely to be street checked than whites. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/street-checks-halifax-police-scot-wortley-racial-profiling-1.5073300 ↵

- The Royal Canadian Geographical Society in conjunction with Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the Assembly of First Nations, the Métis National Council, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation and Indspire.(2021). History of Residential Schools. https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/article/history-of-residential-schools/ ↵

- Dickson, C. & Watson, B. (2021, May 29). Remains of 215 children found buried at former B.C. residential school, First Nation says. CBC News British Columbia. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/tk-eml%C3%BAps-te-secw%C3%A9pemc-215-children-former-kamloops-indian-residential-school-1.6043778 ↵

- Adapted from Sheppard, R. (2019, July 23). Black education - A failing grade for the province. Nova Scotia Advocate. https://nsadvocate.org/2019/07/23/black-education-a-failing-grade-for-the-province/ ↵

- Henry, N. (2021, August 30). Racial segregation of black students in Canadian schools. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/racial-segregation-of-black-students-in-canadian-schools ↵

- Black Learners Advisory Committee. (1994). BLAC report on education: redressing inequity - empowering black learners. https://www.ednet.ns.ca/fr/docs/blac-report-education-redressing-inequity.pdf ↵

- Province of Nova Scotia. (2021, June 11). Assessment of equity in individual program plans will address barriers in education. https://novascotia.ca/news/release/?id=20210611001 ↵

- Woodbury, R. (2016, December 12). African-Nova Scotian students being suspended at disproportionately higher rates. CBC News Nova Scotia. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/african-nova-scotian-students-suspension-numbers-1.3885721 ↵

- One Nova Scotia. (n.d.) Goal 8: Employment Rate - First Nations and African Nova Scotians - Deep dive. https://www.onens.ca/goals/goal-8-employment-rate-first-nations-and-african-nova-scotians ↵

- Statistics Canada. (2017). Nova Scotia [Province] and Canada [Country] (table). Census Profile. 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Released November 29, 2017. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E ↵

- Adapted from Devet, R. (2017, Nov 30). Census 2016: African Nova Scotian poverty rates through the roof, unemployment numbers terrible. The Nova Scotia Advocate. ↵

- Frank, L., Fisher, L., & Sauln, C. (2020). 2020 Report card on child and family poverty in Nova Scotia: Willful neglect? Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Nova%20Scotia%20Office/2020/12/Child%20poverty%20report%20card%202020.pdf ↵

- Frank, L., Fisher, L., & Sauln, C. (2020). 2020 Report card on child and family poverty in Nova Scotia: Willful neglect? Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Nova%20Scotia%20Office/2020/12/Child%20poverty%20report%20card%202020.pdf ↵

- Beech, P. (2020, July 31). What is environmental racism and how can we fight it? World Economic Forum. ↵

- Bacter, J. (n.d.). For 50+ years, pulp mill waste has contaminated Pictou Landing First Nation’s land in Nova Scotia. CBC DOCS POV. For 50+ years, pulp mill waste has contaminated Pictou Landing First Nation’s land in Nova Scotia ↵

- Ore, J. (2018, February 12). A community of widows': How African-Nova Scotians are confronting a history of environmental racism. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/features/facing-race/a-community-of-widows-how-african-nova-scotians-are-confronting-a-history-of-environmental-racism-1.4497952 ↵

- Freeze, C. (2019, November 17). More than one-third of people shot to death over a decade by RCMP officers were Indigenous. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-more-than-one-third-of-people-shot-to-death-over-a-decade-by-rcmp/ ↵

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2020, August 10). New OHRC report confirms Black people disproportionately arrested, charged, subjected to use of force by Toronto police. https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/news_centre/new-ohrc-report-confirms-black-people-disproportionately-arrested-charged-subjected-use-force ↵

- Ray, C. (2019, October 18). Street checks permanently banned in N.S. after review calls them illegal. CBC News Nova Scotia. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/halifax-street-checks-illegal-1.5326217 ↵

- Government of Canada. (2014). A case study of diversity in corrections: The Black inmate experience in federal penitentiaries: Final report. https://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/rpt/oth-aut/oth-aut20131126-eng.aspx ↵

- Luck, S. (2016, May 20). Black, Indigenous prisoners over-represented in Nova Scotia jails. CBC News Nova Scotia. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/black-indigenous-prisoners-nova-scotia-jails-1.3591535 ↵

- Gunn, B. L. (n.d.). Ignored to Death: Systemic Racism in the Canadian Healthcare System. Submission to United Nations Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP). https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/IPeoples/EMRIP/Health/UniversityManitoba.pdf ↵

- Page, J. (2021, May 27). Joyce Echaquan died of pulmonary edema, could have been saved, inquiry hears. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/joyce-echaquan-inquiry-toxicology-1.6042783 ↵

- Snan, N. (2020, June 6). How anti-Black racism affects the health of Nova Scotians of African descent. The Chroncile Herald. https://www.saltwire.com/halifax/news/local/how-anti-black-racism-affects-the-health-of-nova-scotians-of-african-descent-458879/ ↵

- Nayan, F. (2020). Raising Multiracial Children: Tools for Nurturing Identity in a Racialized World (p.200). North Atlantic Books. ↵

- San José State University. (2020). Terms Related to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. https://www.sjsu.edu/diversity/office/education/terms.php#D ↵

- Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang quoted in Ritskes, E. (2020, September 21). What is decolonization and why does it matter? IC. https://intercontinentalcry.org/what-is-decolonization-and-why-does-it-matter/ ↵

- ibid ↵

- Ritskes, E. (2012, Sept. 21). What is decolonization and why does it matter? IC. https://intercontinentalcry.org/what-is-decolonization-and-why-does-it-matter/ ↵

- Two-Eyed Seeing – Elder Albert Marshall’s guiding principle for inter-cultural collaboration. Institute for Integrative Science & Health (IISH). http://www.integrativescience.ca/uploads/files/Two-Eyed%20Seeing-AMarshall-Thinkers%20Lodge2017(1).pdf ↵

- Pete, S., Schneider, B., O’Reilly, K. (2013). Decolonizing Our Practice - Indigenizing Our Teaching. First Nations Perspectives 5, 1: 99-115. https://iportal.usask.ca/index.php?sid=224669526&id=46594&t=details ↵

- Dei, G.S. (1996). Anti-Racism: Education Theory and Practice. Fernwood Publishing. ↵

- Section copied from Diversity Arts Australia and The British Council. (n.d.) Call out & call in racism. In the Creative Equity Toolkit. https://creativeequitytoolkit.org/topic/anti-racism/call-out-call-in-racism/ ↵