Chapter 9, Using the Computer in Training

Objectives

This chapter will help you

► identify the uses for a computer in training

► recognize how a computer functions

► understand the hardware and software of computers

► recognize the interactive role of computers and video

Introduction

Whether we like it or not, computers touch the life of every person in a variety of ways. They keep track of our electric and gas bills, balance our checking accounts, keep track of our credit-card expenditures, control traffic, direct airlines, make theatre reservations, and arrange dates for us. For those of us interested in communication training, the computer is making inroads that offer both excitement and challenge. As we said in chapter 2, a trainer has to be able to cope with innovation and change. The computer is certainly creating both in training.

In the last chapter we talked about the computer as an aid for the presentation of information in training. In this chapter, we will focus on the computer’s role in the development of training materials and as a potential replacement for the trainer. If video was the innovation of training for the 1980s, the computer with video is the training innovation of the 1990s. We will discuss this role of the computer at the end of the chapter.

Before you panic at the thought of having to use a computer, we would like to arrest your fears. For most of the computer functions that we will consider in this chapter, you do not need to know how to program a computer. You will need to know how to use a microcomputer (one that fits on the top of a desk). If you know how to type and use a small calculator, you can use a micro. The mystique of the computer must be overcome since it will be an integral part of daily existence. You cannot shop at the supermarket or use an automatic teller machine (ATM) without coming in contact with a computer. In fact, most students in our elementary and secondary school systems have had the chance to become computer literate. We have done it, and we know you can too.

The best way to get to know about microcomputers is to browse the various computer stores in your location. Take demonstrations and read about the various functions and features of each of the computers. If you don’t already own a computer, read the rest of this chapter and any of the popular books on the market that describe the uses and types of microcomputers currently available. Make sure that the computer you buy can do all that you want and still have the capability of growth for future uses.

We will not refer to specific brand names for computer programs (software) that are currently on the market because to do so would date the book. By the time this book goes into production, a whole new generation of software programs could be available.

Functions of the Computer

We would like to broaden your view of what computers can do for you as a trainer. Today’s computers can do much more than analyze your data and keep recipes for future use. We will explore the five basic functions of the computer for training purposes: instructing, creating, accounting, analyzing, and communicating. How you use these functions will vary with your needs and your abilities. As we examine each of these functions, we will illustrate them with examples from various training segments in our field.

The computer’s ability to store materials and analyze information frees the trainer for the important tasks of needs assessment and instructional design. To give you an example, both authors keep all of our training materials on computer disks so that we can use what may be appropriate for a given client. As we said earlier, we believe that each program should be designed specifically for the client. For example, we may keep a file on the barriers to communication in the computer. When we are going to talk about the barriers to communication for organization XXX, we just retrieve the communication barriers from computer storage and tailor them to the organization. When we work with organization YYY, we could apply the generic barriers to their situation.

Instructing

The disciplines of psychology and education have relied on computer to assist learning. We can look at the two instruction applications of computer-assisted instruction (CAI) and computer-managed instruction (CMI). Computer-assisted instruction can involve direct instruction or can be used to assist the presentation of material by the trainer.

Direct instruction usually involves the presentation of material by the computer followed by questions that, if you get them right, allow you to proceed to the next section. If you select the wrong answer, you may be directed to review the material and to then make another selection. For example, let’s assume that the material in this chapter was just presented by a computer and we want to know if you understand the concepts. The computer might now ask you:

If you select d, the computer might respond: wrong, please reread the material. If you said a, it would proceed with more material or would present additional questions.

Such a process was called programmed instruction before we introduced the computer into the process. The same material, questions, and messages were provided in book form. You would read the material, answer a question, and turn the page to see if you had the right answer.

With computer graphics, we can enhance the messages we present to the trainee. In other words, we can use a visual aid within a visual aid (the computer). So we could use some computer-generated visuals to highlight key points for a topic we are teaching by computer.

One obvious advantage of CAI is that it allows the trainee to pace the instruction according to his or her own needs. If you have a number of computers or, conversely, a small number of trainees, you are free to help individual trainees as they progress through the program. Rather than lecturing, you are able to function as a true facilitator.

CAI also can be used after initial instruction as a form of repetition or drill. If you have conducted a session on the proper use of adverbs in written communication, you could save computer-generated messages that could check the trainee’s understanding of the concept of adverbial use. Likewise, you can use CAI with the simulations, games, and other training activities discussed in chapter 7. You are only limited in your use of CAI by the availability of commercial programs or your ability to write computer programs on your own. We will discuss computer programming later in this chapter.

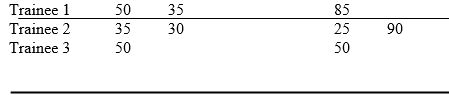

Computer-managed instruction has limited value to the communication trainer. Unless you are required to keep track of the progress of your trainees, you will not use the commercially available programs for CMI. Such programs keep track of trainees on a large number of exercises and give you a total performance score. This is useful if you have a large number of trainees and a number of training programs that can be taken in any order. For example, if you were running a training program for a company, you could track all of the employees who have gone through training, monitoring each trainee’s progress. A print-out of your training log might look like the following:

Training Topic

Listening Group Process Public Speaking

As you can see, only Trainee 2 has completed all three training units.

If you were required to test trainees on a given topic, CMI allows you to compile a test item pool from which you could select questions for a given test. The computer will even select the questions if you tell it how many you need. Theoretically, you could have a different test for each trainee. CMI can be very useful for training programs that must test for certain proficiencies.

With CMI you are creating what the computer people call a spreadsheet (see above example discussing training topics). There are numerous such software programs available commercially for your use. We would caution you to find an integrated package of software that is compatible with others. For example, you would want software that allows you to move from spreadsheets to word processing and even to graphics programs without difficulty. Again, there are a variety of such packages on the market and we will not endorse one over the other. Why is integration important? The authors of this book are currently using two different packages of software, which means we must reenter (type) each other’s material if we are going to make revisions via the computer. Needless to say, this is a time-consuming process and would be entirely unnecessary if we had used the same software package.

Another CMI tool is that of a computer modem. Essentially this is a device that allows you to communicate from your computer to another computer via a telephone hookup. This is important if you are working with a trainer in another city and want to share information quickly. For example, you could prepare your training materials and send them to your colleague for revisions via a modem. The revised material could be returned by modem to you in a relatively brief period.

The modem also allows you to retrieve data from the Internet, a system of linked computers from which you can retrieve information and materials from all over the world. For example, we wanted the phone number of a colleague at Ohio State University so we went through the Internet to a phone directory on the campus and retrieved the address, phone number, and some other demographic data about our colleague. At the risk of dating the book, we will talk more about the Internet later in this chapter.

The modem is central to your ability to communicate with the rest of the world so you should make certain that it is included with the computer you purchase, or that you can add it to whatever system you purchase.

CAI and CMI offer the trainer instructional opportunities to enhance learning for the trainee. It should be obvious that the computer cannot take the place of the trainer, at least not in its present form. Like audiovisual aids, which we discussed in the last chapter, the computer supplements your role as a trainer.

Creating

The most exciting prospects for the computer are yet to come. Considering the impact of the computer thus far has been limited to linear and numerical approaches, it is clear that by extending the range of the computer to three dimensional spaces, as we have seen with computer graphics, a visual revolution is at hand. With these graphics capabilities, you will be able to create exciting simulation and learning games for your trainees.

As we said in the beginning of this chapter, you do not need to know how to program a computer for most of what you can do in training. However, if you want to make maximum use of the creating function of your micro, you will need a working knowledge of a computer-programming language, unless your employer can provide a computer programmer for your unique uses.

Which languages you should learn and where you get the training are your choices. If you are still going to school, you might turn to the computer science department or business school for a basic computer-programming course. If you are out of school, you might look at community colleges for the same courses or explore what computer stores provide in the way of training. Another alternative is to use CAI and let the computer teach you how. Unfortunately, most computer manuals are not written with effective communication and clarity in mind. This approach may take you a little longer and be frustrating, but don’t give up. It is well worth the effort.

Perhaps the most widely used creative function of the computer is word processing. This entire book was written using word processing software. What is word processing? It is a glorified way of saying we sat down at a computer and typed the chapters. As stated earlier, we word processed all of our training materials and stored them on computer disks (think of disks as blank records on which you save information).

The big advantage of word processing and storage for the trainer is the ability to move, insert, and delete information in order to customize your training programs. For example, you may have to do a training program on presentation skills for a company. In storage (on a disk) you have materials on presentation skills that you used for a previous client. Using word processing, you can transfer portions of that previous program into your new document without having to retype the entire package. Over a period of time, you might have ten or more versions of a particular program that you can edit as needed.

Once you have the basic word-processing software, you can add a spelling dictionary, thesaurus. an outline function, and even check your grammar before you print a final copy. These features alone can save the trainer a lot of embarrassment with handouts. Remember, your credibility as a trainer is constantly on the line.

You can use word processing for a lot more than storing and editing training materials. If you need to develop questionnaires for needs assessment, the computer can facilitate it. You can put proposals to conduct training into storage as well. Once you have the material on a disk, you can save yourself time in drafting proposals and even final reports. For example, suppose you have submitted a proposal to do a needs assessment and training to the Triple Z Corporation. At the completion of training, the president of Triple Z would like you to submit a final report with recommendations for further follow-up. As you sit at your computer, you can have your original proposal on part of the screen (window), your training materials on another part of the screen, and can use the space remaining to write the final report. Any time you want material from your proposal or training documents, you insert into your final report those sections. Most software programs will allow you multiple windows to view several documents at once and patch back and forth. By analogy, you are painting a picture (final report) by combining what you see from several windows, all available at once.

An interesting series of software programs is emerging that enhances your creating capabilities. You are limited only by your imagination in drafting initial concepts or themes. If you have taken a small-group communication class, you probably had an opportunity to brainstorm. Now the computer can do a large part of that for you. The software brainstorms new combinations for the ideas that you developed originally. We do not want to focus on the types of software that can do this type of creating as they are changing on a daily basis. You need to examine what is currently available.

While the computer can aid you in the creating process, it cannot replace the creative act (so far, that is). If you cannot find the software you need to help you in the creative act, you may need to learn how to write (program) the necessary instructions so that the computer can help. Learning to program a computer is very useful to the trainer but it is the last step, not the first. If you know how to use software with your computer, you will be able to function fully as a trainer without programming skills. Adding those skills will take you one step beyond to make maximum use of your computer for creative training purposes.

Accounting

When we discussed the use of spreadsheets earlier in this chapter, we were talking about an accounting function of the computer. Trainers need to keep track of training materials, budgets, fees, schedules, clients, and appointments, to name a few. Effective use of the computer can organize these for you. Again, you will have to select the appropriate software programs or write them yourself. We recommend the former as it is easier.

For keeping track of schedules, appointments, and miscellaneous ideas, choose a type of software that is always at hand on the computer and can be turned to as needed. For example, if you are busy writing a training proposal and you get a call to set up a meeting, you can switch to your computer appointment calendar and schedule it. You can even make notes in your calendar for expenses, and so on. If you need a printed copy of your schedule, it is at your fingertips.

Whether you are working as a trainer in-house or as an outside consultant, you can use a spreadsheet to account for your various training programs. You can monitor all of the employees in the various stages of training, as we suggested earlier when we were discussing the computer-managed instruction function of the computer. You also can keep track of expenses, mileage, and other items required for tax purposes.

The beginning trainer will have less use for the accounting function of the computer, but if you start with such a program, you will be ready as the need arises. As we have stressed throughout this chapter, it is better to have too much capacity and software than to have too little and not be able to add because your computer does not have the capacity.

Analyzing

Another major function of your computer for training is that of analyzing. Essentially, we are talking about the computer’s ability to analyze data. For example, suppose that you gave all of the employees of your firm an attitude questionnaire about their views of the company. What do you do with the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of questionnaires that you collect? You could list each respondent’s answers to the questions, or you could develop summaries of responses based on the averages of all the respondents. (If you are going to be using a computer to analyze data and do not have a basic knowledge of statistics, we suggest you review some elementary statistics reference materials.)

Entering all of your questionnaire data on the computer will allow you statistically to analyze your responses quickly and easily. Once the data is entered, the options for analysis are almost unlimited. You could find out what the majority of female employees thought about a particular issue, or what the employees who had worked for the company for more than ten years thought, compared to those who were new. Your only limits on analysis will be what you entered into the computer initially. If you did not ask the age of the employee, you could not use age as a basis for comparison.

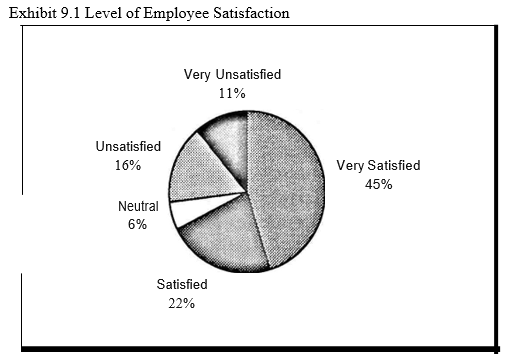

Once you have analyzed the results and have a composite picture of employee attitudes. you could use a graphics software package to render striking visual images for the reader of your report. For example, if employees were asked how satisfied they were with the company. a graph of their responses might look like the pie chart in Exhibit 9.1.

The uses of the computer for analysis are endless. As with all other functions of the computer, you are limited only by your knowledge of the computer’s capabilities and your ability to use the software that is currently available.

Communicating

The newest and one of the most exciting uses of the computer is for communication. While members of universities have had limited ability to communicate with each other by computer, new technology has made such communication available to anyone with a computer, a modem, a phone line, and cash. You need the cash to connect to some system that will transmit your communication to others. The computer, modem, and phone line are your taxi or communication link to friends, colleagues, families, libraries, and data depositories around the world.

We will not discuss specific services currently offering this connection, only what you can accomplish generically. For example, your computer can serve as a fax machine. After generating a message or letter on your word processor, the computer can send it to a regular fax machine or to a computer which can read it as hard copy or as a file to be edited by the receiver using his or her own word processing. For example, the authors faxed chapters of this book back and forth to each other’s computer. One could revise the other’s material without making a paper copy. That same message may be sent by one of the Internet services, which would treat it as electronic mail. If you are sending your message as a fax, you need a phone line and a fax machine or computer at the other end. As an e-mail, you need a system that allows you to send or receive messages.

The computer as a tool for communication is still in its infancy. We would quickly outdate this book if we listed what is currently available – the technology for communicating via your computer will make great strides over the next several years. As trainers, we will be inhibited only by our ability to use the computer and our willingness to spend the money for the technology.

Emerging Uses of the Computer

By now, we hope you realize the potential and the value of the computer for you as a trainer. We would like to conclude this chapter with a discussion of the computer as an integral part of a self-contained training program. By linking the computer with videotapes or videodiscs, you could prepare and deliver an entire training program. We began the chapter by talking about the computer as a teaching tool that both presented the material and tested users on their understanding of concepts. Combining the computer with video will allow you greater flexibility in the training function.

Visualize the following scenario. You want to teach a unit on leadership style in small groups to a number of new middle managers in your organization. You could develop a computer-training program that combines video examples (good and bad) of the various leadership styles. Each middle manager could go through the program at his or her own pace and not only learn the material but also practice the skills by identifying the leadership styles from video illustrations. Numerous examples could be called forth by the computer to meet the differing needs of the middle managers.

Using such a software program requires additional skills from a trainer. You must produce the videos as well as develop the computer-training package. There are software programs currently on the market that will direct you through the design and development process.

As with any training program, you must make certain that you are meeting the needs of the trainees and that the material you are delivering via the computer is as informative and interesting as it would be using the traditional formats of lecture, discussion, and case studies.

We could not end this chapter without speculating on the future of the computer in training. Although we now have computers that are voice activated, they are not ready for mass production and widespread use in training. When that time comes, new training programs via the computer will emerge. In 1966, we suggested the day would come when a trainee could be videotaped making a presentation and the computer could be used to make an analysis of the message’s effectiveness for a given audience. Using interactive video and computer programs, a trainee could present case studies orally and be given feedback by the computer, complete with an analysis of both the verbal and nonverbal dimensions of the presentation. Does this sound farfetched? It’s not. That day has arrived and we, as trainers, have to be ready to implement it in our training programs.

Summary

We have selected to talk about general uses of the computer rather than list all of the hardware and software that is available. In the six years since the first edition of this book, one word-processing software has published six new versions. We would hope that the prospects of the computer would entice you to familiarize yourself with what is currently available.

The computer has progressed from a tool that can speed up complex, time-consuming tasks, to one that can make the editing and revision of text simple. It has advanced from accounting functions to diagnostic functions. For the trainer it has become the one piece of equipment that can make your work easier. It can never replace the trainer, but it can and will make you more effective.