Chapter 10, Evaluating Training Programs

Objectives

This chapter will help you

► understand both the importance and the complexity of evaluating training programs

► identify various ways to evaluate programs

► recognize the strengths and weaknesses of evaluation methods

► identify ways to relate training to job performance

Introduction

One of the hardest things about training is evaluating it. How can you tell whether a program is effective or not? How do you measure its degree of effectiveness? What is the relationship between how much trainees liked a program and how much they learned from it?

Ironically, the degree of difficulty in evaluating programs is topped only by the political importance of the evaluation process. In many organizations, budget cuts often mean the training budget is the first to be pared down. This is an inappropriate decision in the long run, because it affects the organization’s ability to perform well and grow. Many managers, however, feel short-term pressures more intensely than long-term needs. Without a clear idea of how training affects immediate performance in addition to long-range goals, managers easily dismiss its importance. Knowing this, the trainer must present results in terms managers understand. What specific effects did each training program have on immediate employee performance, as well as long-term performance, and how do these immediate effects translate to the bottom line?

Evaluating training is important, then, in at least two ways. First, it helps trainers learn what works and what does not. Through this information, trainers can improve the quality and effectiveness of their programs. Second, the evaluation process gives trainers a way to show management how the programs affect immediate as well as long-term needs. Because of the relatively weak political position of T & D, the trainer can benefit from using evaluation as a sales tool when dealing with other managers. The more clearly managers can see a relationship between how well trainees learned something and how much this learning improved current work performance, the more managers will support T & D.

The trainer must come up with evaluation procedures that are useful to him or her, to management, to teams, and to individual employees. There are several ways to evaluate training programs. The appropriateness of each method depends on various circumstances.

Trainees’ Immediate Responses

Immediate responses from trainees come in two forms: the trainees’ opinions of a program and the trainees’ test results.

Trainees’ Opinions

The most frequently used trainee response is opinion, usually in terms of how much a trainee liked a program. For example, a typical evaluation sheet asks questions such as these:

- What is your overall rating of this program?

Excellent

Good

Average

Fair

Poor

- How did the program match your expectations?

Exceeded them

Met them

Fell below them

- What is your overall rating of the trainer?

Excellent

Good

Average

Fair

Poor

- What is your rating of the audiovisual materials?

Excellent

Good

Average

Fair

Poor

- How well organized was the material presented?

Very organized

Fairly organized

Poorly organized

- How useful will this program be to you on the job?

Very useful

Somewhat useful

Not useful

While these evaluation questions may be reasonable enough, it is important to notice what they measure. They measure the trainee’s opinion of the program – whether he or she liked the material, the trainer, the visual aids, and whether the trainee thinks the program will help him or her at work.

One weakness of these types of questions is that there is no clear relationship between liking and learning. Trainees may find a program humorous, entertaining, lively, and a good break from work, but may not necessarily learn anything that benefits them or the organization. As an example, one company offered two programs for secretaries: a how-to course in time management and telephone etiquette, and a motivational course designed to boost office morale. The programs were held in adjacent rooms.

Throughout the day, it was clear that the how-to course was, surprisingly, more entertaining than the motivational course, because trainees in the second program heard laughter all day from the room next door. The next day, however, it became clear that while the how-to program was fun, it did not teach much to the trainees: none of them remembered anything about time management or telephone etiquette skills. Enjoyment, then, is different from learning.

Another weakness of such questions is that trainees are not qualified to judge the relevance of material. Their input is important as a way of judging how well the trainer related the material to work situations. But trainees do not have as complete a picture of the organization, their departments, their teams, or even their jobs as do trainers and managers. The evaluation questions listed are useful ways to measure the trainees perceptions of a program, but not to measure the program’s effectiveness. In an engineering firm, for example, employees were asked to attend a program in interpersonal skills. None of the engineers who attended did so willingly: they did not see how interpersonal skills related to their drafting and designing work. From their managers’ points of view, however, the engineers needed to develop these skills because the managers knew that due to changes in the company’s marketing approach, many of the engineers eventually would be dealing more directly with clients. Because the managers had decided not to announce the changes until appropriate individuals were identified, the engineers were unaware of the need for the program, even though the managers knew it was relevant. Trainees, therefore, often are not able to judge the appropriateness of a training course. While the trainees’ opinions – the first type of immediate response – are important in terms of identifying trainees’ preferences and perceptions, they are not meaningful ways to evaluate the effectiveness of a program. To judge effectiveness, trainees’ test results – the second type of immediate response – are more useful.

Trainees’ Test Results

A second type of immediate response from trainees is their scores on tests designed to measure how much they have learned. This response is more useful than opinion if the test does indeed measure what it claims to measure. As every student knows from classroom experience, doing well or poorly on a test does not necessarily reflect what is actually learned. Designing tests that accurately measure participants’ learning is a difficult and challenging aspect of training.

One way to allow for legitimate testing is to clarify at the design phase of a program the objectives of the course. What will trainees know at the end of the program? If the trainer wants them to know the names and positions of engine parts, a clear way to measure this knowledge is to present, at the end of a program, a diagram of an engine and have trainees label the parts. If the objectives of a course include knowing company policy regarding confidential information, trainees can be asked, at the end of the course, to write down what the company’s policy is. In both these cases, the trainer can tell whether objectives have been met by how accurately trainees answer these questions.

One weakness of this testing, however, is that open-ended questions such as “What is the company policy about confidential information?” lead to long essay-style answers that are both time consuming to evaluate and hard to standardize for comparisons. For these reasons, written tests often are in true-false or multiple-choice formats. In the case of company policy, sample questions might be:

- Confidential information is labeled with “XR.” T F

- If a caller asks you for information that you think might be confidential, you should:

a) ask your boss what to say

b) refer the caller to the public relations department

c) give out the information

d) get the caller’s phone number and give it to the information officer

These types of questions have weaknesses of their own. Multiple-choice and true-false questions often measure a trainee’s ability to recognize rather than remember information. Fill-in questions provide a way to emphasize recall. A fill-in question might be:

- Confidential means the information is available only to Personnel.

As with essays, fill-in answers may be time consuming and may lead to decision making about answers that are only “close.”

Another weakness in testing is that trainees may get good at test taking, but not at applying the information to work. Every classroom has students who score well on tests but do not know how to use the information. Several ways to resolve this problem are discussed in the next section.

Another issue to consider in testing is whether trainees actually learned from the training program, or whether they may already have had the information. A way to determine this is to use the pretest-posttest method. At the beginning of the session, before any training starts, participants answer a pretest, that is, a test asking for knowledge about the information that is going to be covered. At the end of the training session, the trainees take a posttest – the same test that was used as the pretest. Ideally, the difference in scores would indicate how much the trainees learned. For example. if most of the trainees got 0 or 1 correct answers on a pretest of 25 questions and then got 24 or 25 correct on the posttest, these results would indicate that the trainees learned a great deal in the program. If they got 24 or 25 correct on the pretest, they obviously would not need the program. And if they got only 1 correct on the posttest, it would mean the program was not successful. A problem with this method, however, is that the very act of taking a test, as in the pretest, may tell trainees what to pay most attention to during the program. In addition, taking the same test twice – using “repeated measures,” in research terminology – may improve trainees scores simply on the basis of random chance. The pretest-posttest method has its limitations, although it can be very useful. Other testing methods are discussed in the section entitled “Types of Evaluation.”

Trainees immediate responses take two forms: opinions and test results. Their opinions are important in terms of telling trainers how receptive trainees are to existing and future programs. Test results, however, are more accurate measures of a training program’s effectiveness. Accurate testing requires clear, specific objectives.

Relationship to Performance on the Job

Managers are eager to know whether training pays off on the job. As mentioned before, learning information does not necessarily translate into learning new behaviors. For example, in a workshop about performance appraisals, one manager consistently gave good answers when the trainer asked such questions as “What is the best way to use the appraisal as a form of motivation?’ or ‘How do you help an employee feel comfortable about the appraisal?” Based on these answers, it would be easy to assume that this manager was proficient in giving performance appraisals. On the job, however, the employees in this manager’s department were upset because of his blunt, negative comments. Clearly, the manager knew the right answers but was not able to use them. The same problem exists when a mechanic labels diagrams accurately on tests but cannot repair an engine on the job, or a receptionist correctly lists the five steps of telephone etiquette but speaks rudely and hangs up when callers irritate him or her. The information is of little value unless it improves behaviors on the job.

Types of Behaviors

Behavioral objectives must be set for programs designed to influence behaviors at work. Just as informational objectives state what a trainee should know at the end of the program, behavioral objectives state what the trainee should be able to do.

Sometimes these objectives can be measured immediately after the course. In a programming course, trainees are asked to design and run a certain type of program. In a hair-styling class, trainees demonstrate what they have learned by cutting and setting hair. These examples refer to specific skills that are relatively easy to observe and measure at the end of a training program.

Other behaviors require both time and the reactions of coworkers, employees, or bosses before they can be measured. For example, suppose managers took a course in ways to delegate. An informational test may measure how much the managers know, but only time and employees’ reactions can tell how well they use what they know. In this case, the managers would practice the new delegation skills for a certain period of time-say, two months. During this time, employees would learn what effects the managers ‘ delegation styles have on them. Do the managers select them for tasks on the basis of skills and interests, instead of favoritism or convenience? Do they give them enough authority along with responsibility? After this time period, employees would fill out – anonymously – a questionnaire asking such things as:

- Compared to six months ago, has your manager improved his or her delegation skills?

Yes No

- Does your manager make clear what you are expected to do?

Yes No

- Does your manager give you enough authority to carry out assigned responsibilities?

Yes No

Based on employees’ responses, the trainer and the managers can determine the effectiveness of the program in behavioral terms. This same process may be used at any level in organizations.

Several months after having employees attend a training course, bosses might fill out – anonymously – questionnaires about changes in employees’ behaviors at work. If, for example, the training program dealt with time-management and organizational skills, the questions might include:

- Do your employees manage their time more effectively now than they did six months ago?

Yes No

- Does their work appear to be more organized?

Yes No

Sometimes, coworkers evaluate each other’s work performance after a training program.

In all cases, the questions asked would be based on the behavioral objectives of the program: what trainees should be able to do on the job after the training. Whether the behaviors are immediately observable skills or longer-term behaviors within a broader context, they can be identified, asked about, and used at work.

The Bottom Line

Remember that the broad, long-term goal for all training is organizational productivity. In addition to specific job-related skills and behaviors, individual employee development, and improved departmental performance, training aims at increasing organizational effectiveness.

Effectiveness and productivity are difficult enough to measure. In most organizations, the bottom-line definition of these terms includes lower turnover, lower absenteeism, greater number of units produced, higher quality of production, increased sales, fewer accidents, lower costs, and increased profits. These outcomes are measurable in that they deal with numbers. What is hard, however, is determining how much these results are due to training and how much they are due to other circumstances, such as pay raises, the general economy, competition, new management, or other events. Even harder to measure, and harder to identify the source of, are such things as office morale, motivation level, dedication, support, and commitment.

Despite the difficulties in defining, measuring, and identifying causes for these outcomes, they are meaningful to organizations. Trainers must use cost-related measures when possible and, at least, behavioral objectives and outcomes to identify their contribution to the organization’s bottom line.

Types of Evaluations

The pretest-posttest method was discussed briefly under the “Trainees’ Test Results” section. While this probably is the most commonly used method in training, its weakness, again, is that there really is no way to determine whether increased knowledge indicated on the posttest is due to the training program or to other factors. Suppose a hotel holds a training program in housekeeping methods and several months later the rooms are noticeably cleaner. The posttest results – that is, the cleaner rooms – may be due to the program, but they also could be related to other circumstances, such as new vacuum cleaners, better-quality cleaning products, management’s recent emphasis on improved room care, or any other possible causes. The pretest-posttest method does not say much about what caused the changes. To evaluate more accurately the effectiveness of training, several other testing methods are useful.

After-Only Design with a Control Group

Remember that the problem with the pretest-posttest method is it does not clearly identify training as the reason for improved knowledge or performance. In the after-only design method, a control group is used to determine whether training made the difference.

In research, a control group is one that does not get the treatment you are measuring. In this case, the treatment would be the training program. The control group in an organization would be employees who did not get the training experienced by the treatment group, or the trainees. To keep everything else as equal as possible, the control group should be as similar as possible to the treatment group in terms of job titles, age, experience, gender mix, and other factors. Random assignment of employees to either the treatment or the control group ensures statistical equality between groups.

Using this method, no pretests would be given. The treatment group would go through the training program, while the control group would not. Both groups would take the posttest after the training was over. Suppose both groups scored about the same; this would mean the training had no effect, because the untrained group scored just as well (or just as poorly) as the trained group. In this case, training clearly made no difference. Suppose, however, the trained group scored much higher than the untrained group. Because the groups were equal in everything except the training, these results would indicate that training made the difference. Data analysis is used to determine whether the differences in scores are statistically significant or simply due to random chance.

There always is the chance – unlikely though it is – that the treatment group would score lower than the control group, meaning the training hurt trainees’ skills! This is an example of a trainer’s nightmare, and in the unlikely event that it occurs, the trainer’s job is then to reexamine the program and the identified needs. Remember, everyone learns from mistakes.

Pretest-Posttest Design with a Control Group

In this method, employees again are randomly assigned to a treatment group or a control group. Here, both groups take a pretest, only the treatment group receives training, and both groups take a posttest.

Both groups are equal statistically, which means that differences in scores on the posttest can be attributed only to the training program, and not to group differences in intelligence, experience, or other factors. One advantage to this design is that the pretest results ensure equality between the groups. In case the results indicate inequality, statistical techniques may be used to correct the imbalance. Once again, statistical analysis determines whether differences in posttest results are significant – that is, whether they are due to the training program – or whether they are due to random chance.

Time-Series Design

While both methods just described use a single pretest or posttest, the time-series design uses a number of measures both before and after training. The purpose of this method is to establish individuals’ patterns of behavior and then see whether a sudden leap in performance followed a training program. By having many data points to identify patterns, large variations legitimately can be attributed to the program.

One weakness with this method is that because of the relatively long time period covered, even large changes in behavior can be attributed to circumstances other than the program. For example, one company was eager to increase morale among employees in one department. Various training sessions were implemented, and because the topics included motivation and goal setting, top management expected that the sessions would increase morale.

Periodic testing indicated a sudden leap in morale, and management was tempted to interpret the leap to mean the sessions were successful. The leap, however, coincided with replacement of the department’s manager. Obviously, the increase in morale could be attributed to more than one event. Here again, use of a control group can make a difference. All employees would have gone through similar circumstances, such as changes in management, raises, job pressures, or other events.

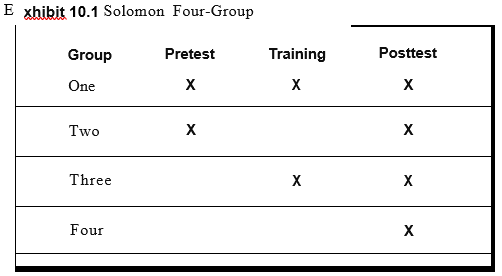

Solomon Four-Group

This method uses more than one control group, and its purpose is to minimize the effect that pretesting may have on trainees. Because of the possibility that the act of taking a pretest changes trainees’ attitudes toward the program, this complex design attempts to account for these effects.

In this method, trainees are randomly assigned to one of four groups. Group 1 is a treatment group – that is, a group receiving the training – that takes a pretest and a posttest. Group 2 is a control group that takes the pretest and posttest but takes no training. Group 3 is a treatment group that gets training and takes only the posttest, and Group 4 is a control group that does nothing but take the posttest (see Exhibit 10.1).

With this design, neither control group has received the training and only one has taken the pretest. Through statistical analysis, the trainer can determine what differences both the training and the pretest made. One major limitation with this method is that it is not really practical in ongoing organizations. Nevertheless, it is used in research projects when the situation allows for it.

Multiple-Baseline Design

Another complex method is the multiple-baseline design. The method compares the performances of individuals within groups, rather than between groups. In this case, the multiple baselines are the individuals’ current levels of performance. Differences – and, it is hoped, improvements – in each person’s level of performance are compared to the original baselines. The individuals are controls for themselves.

The trainer who uses this method is trying to determine whether improvements occur only after training programs, or in some other random fashion. Suppose the baselines of individual salesclerks showed certain levels of performance in terms of accuracy and speed on the computerized register, and suppose the clerks take a training program in using the register, after which their speed and accuracy increase. If this procedure were repeated over time, and the pattern showed that performance increased after training, and only after training, the results would indicate that training made a difference.

All these methods provide various ways to evaluate the effectiveness of training programs and to determine that it truly was training that made the difference. Because of their need to “prove” its worth in terms of the bottom line, trainers must consider the evaluation aspect even when designing programs. It would be to the trainer’s advantage to keep management posted regularly about evaluation results.

Long-Term Implications

A combination of things makes evaluation a key element of training. As mentioned earlier, management must see the direct relationship among training, behaviors, performance, and the bottom line. The trainer truly must sell this relationship to management. Computer technology allows for sophisticated and usable statistical analysis to serve as a tool for the trainer. Because the evaluation procedure is crucial both in terms of its implications about training programs and its political uses, the trainer must identify the appropriate evaluation method while designing the program.

Despite the emphasis on the need to use statistics in the evaluation process, a word of caution is in order. Sometimes, the computer and statistical processes can seduce a trainer into a “research for research’s sake” approach. Remember that the purpose of training is practical – that is, the results must be relevant and useful to the organization and to society. Research is valuable, but only if it is applicable to the needs of the trainees and the organization.

Summary

The evaluation process is both a difficult and crucial part of training. Programs can be evaluated in a number of ways. One category of evaluation methods involves trainees’ immediate responses. These methods include trainees’ opinions and trainees’ test results. Another category of methods attempts to measure the relationship of training to performance on the job. These methods are concerned with types of behaviors and the bottom line.

Types of evaluations include pretest-posttest, after-only design with a control group, pretest-posttest design with a control group, time-series design, the Solomon four-group, and multiple-baseline design.

Because training departments are politically weak in most organizations, trainers can use the evaluation process to show managers the contributions training makes to the organization. The trainer may use statistical methods to strengthen his or her position, but must remember that the bottom line always must be practical and usable.