Chapter 5, Presenting Proposals and Assessments

Objectives

This chapter will help you

► identify the three types of proposals for training

► design proposals for effective presentations

► recognize the differences in pre-assessment and

needs-assessment proposals

► understand training proposals

Introduction

If we did everything that was outlined in the previous chapter, the result is a thorough needs assessment of an organization, and we need to know just exactly what to do with it. In this chapter, we will talk about how one goes about presenting needs assessments and even proposals to do needs assessments, as well as how to present training proposals to management. Comments that we have to make here will apply both to the in-house trainer and, even more so, to a consultant who has been retained by an organization. Needless to say, the outside consultant has a bigger job in presenting proposals and assessments because the bottom line for this consultant is his or her very livelihood. The in-house consultant may have the security of being an employee of the organization, but still needs to make a strong case for the assessment and the training. We will take a look at presenting proposals and assessments in the rest of this chapter.

Types of Proposals

Essentially. there are three types of proposals that you can make. We will discuss each type and provide examples, as well as a sample outline for how you might develop a written proposal, which then may serve as a basis for any kind of oral report you may have to or will want to make.

Needs-Assessment Proposals

The first proposal one needs to be familiar with is making a proposal to do a needs assessment. This proposal precedes any needs assessment we might do of an organization. Essentially, what we are saying to our superior, or to the chief executive officer (CEO) if we are an outside consultant, is we think there is a need to take a look at your organization. We would like to propose that an assessment of the organization be made. Sometimes we are asked to do an assessment because the CEO believes there is a need. For example, recently we made a proposal of about eight pages to an organization at their request suggesting that they hire us to do a needs assessment. After we submitted this proposal to do a needs assessment. we were told, “No, the organization will do its own needs assessment.” but they wanted to hire us to do training on what was found as a result of doing the needs assessment.

What, then, goes into a proposal to conduct a needs assessment? It doesn’t vary that much from the needs assessment itself, but simply is a proposal and requires more justification as to why a needs assessment ought to be done. There are three parts to the proposal, as can be seen in the outline in Exhibit 5.1. We would like to discuss each of these three components in some detail.

Exhibit 5.1 Proposal to Conduct a Needs Assessment

- Executive Summary (one page or less)

- Proposed Parameters of the Needs Assessment

- Proposed Procedures

- Population of the assessment

- Sampling plan

- Methodology

- Means of analysis

Executive Summary. The executive summary is the best shot we have to convince whoever reads the proposal that we ought to conduct it. In essence, it is a persuasive communication that encapsulates the entire proposal in a page or less. Why include an executive summary? The answer is clear if one considers the amount of information that decisionmakers have to read on a daily basis. If managers and CEOs are bombarded with a volume of information, they will look for ways to shortcut the process and extract only the relevant information. The executive summary provides that vehicle to aid the manager in decision making. In some cases the manager may circulate the summary to other top managers for review. They may never see or make a decision on the entire proposal.

This executive summary contains an overview, as well as key persuasive arguments to convince the person in charge that this needs assessment ought to be done. The summary must have the ability to stand alone in case it is deliberately separated from the proposal for review. Give the arguments but save the rationale and support material for the proposal.

Proposed parameters.

The second major section of this proposal discusses the parameters. as well as the need for conducting a needs assessment. For example, rumors may be running rampant within an organization and on the basis of the widespread nature of the rumors, we might propose that a needs assessment be done to ascertain not only the source of the rumors, but what might be done vis-a-vis training to reduce the rumors and the tension that may be resulting from them. This section contains a major persuasive appeal for conducting a needs assessment. The parameters might also set out the scope of the assessment. Many times the organization may want you to focus on a particular department or cost center. We recall a student group who was asked to present a proposal to a restaurant but was told up front not to include the kitchen staff. This became a parameter for the assessment. Any limitation that is presented up front is considered a parameter which must be acknowledged.

Some parameters may make the assessment a waste of time. To complete an analysis of a restaurant without exploring the kitchen staff and its relationship to the rest of the organization would be of little value. On the other hand, if you are trying to learn how to complete a needs assessment (i.e., a student), it may be a good learning experience.

By putting the parameters in the proposal, you are signaling the person for whom the assessment is to be done what limitations there might be on the final assessment. Clearly it would be that person’s decision to move forward with the assessment. We are not doing the needs assessment at this point, but simply describing in some detail the reasons the needs assessment ought to be done, as well as the scope of the proposed needs assessment. We are making the sales pitch for the assessment.

Proposed procedures.

The last major section describes the procedures that we would use in order to conduct a viable needs assessment. We want to describe the total population that would be affected by the needs assessment, as well as any procedure we might use to sample from within the organization. So, if we were working in an organization of 10,000 employees, we might say that the population affected by the needs assessment would be all 10,000, but that we would want to sample half of the employees randomly, or maybe a tenth of the employees going across all of the levels within the organization. This would give us a sampling plan and statistically we could work out how representative this sample would be of the overall population.

In our proposed procedures, we would want to discuss the methods by which we would conduct our needs assessment. We described these methods in some detail in the previous chapter, so that information should be incorporated in the proposal we would present to our manager or to a CEO.

In our proposal, we would want to conclude the procedures section by describing how we would analyze the data and determine whether the results warrant further management time, and whether training might be called for.

This assessment analysis might incorporate some statistics. However, you would not want to incorporate “t-tests” or “analysis of variance” if these concepts were Greek to the person reading the report. On the other hand, if the manager or CEO has some statistical background, failure to incorporate such procedures into your proposed analysis would probably result in your not getting the go-ahead to do the needs assessment. You would not want the manager to ask you why you did not use multiple regression if you do not mention statistical procedures.

These three major components of a needs-assessment proposal would average between five and ten pages of description. It is not a good idea to spell out in too much detail what would be done. Otherwise, if you were an outside consultant, the organization could use your proposal and not bother hiring you to do the actual assessment. Your task, then, is to entice the manager into the need for a needs assessment without revealing too much information

We are making the assumption here that a proposal is necessary before conducting a needs assessment. Sometimes organizations simply assume that needs assessments will be conducted on a periodic basis, and thus no such proposals would be necessary. These organizations view the annual assessment of employee attitudes as an integral part of their commitment to effective management.

Needs Assessment

Assuming we have the go-ahead to do a needs assessment, what, then, should be incorporated in the actual assessment? Exhibit 5.2 contains an outline for the typical assessment, whether it’s being done in-house or by an outside consultant.

Again, you can see that the executive summary is a critical portion of the assessment. Unlike the proposal that we described earlier, in the actual needs assessment you will incorporate the results of the executive summary. No longer are we proposing; we are now describing what we found and the means by which we found it.

Exhibit 5.2 Needs-Assessment Outline

| Executive Summary( one page or less) Background and History of the Organization Parameters of the Needs Assessment Procedures - Population of the assessment - Sampling plan - Methodology - Means of analysis Results Conclusions -Issues determined -Recommendations - Training - Non Training |

In the actual assessment, we want to spend a bit of time describing the nature of the organization, including some brief history or background of the problem area on which we’re focusing. For example, if a new division is created within a company. we want to talk about development of that unit if our needs assessment is of that particular division. We do not want to go into a ten- or twenty-page discussion of the founding of the organization, or include any of the historical materials we might incorporate if we were doing an annual report or a history of the company. Some background, however, is important to comprehend the outcome of our needs assessment. If possible, consult with the person to whom the report is to be delivered on how much background and history is needed. She or he can tell you who might read the report and how much background and history is relevant.

The next two sections of the assessment are pretty much the same as the proposal in that we describe the parameters and topic areas, as well as the procedures that we used in the actual assessment. Where the proposal talked about what we were going to do, the needs assessment talks about what we actually did.

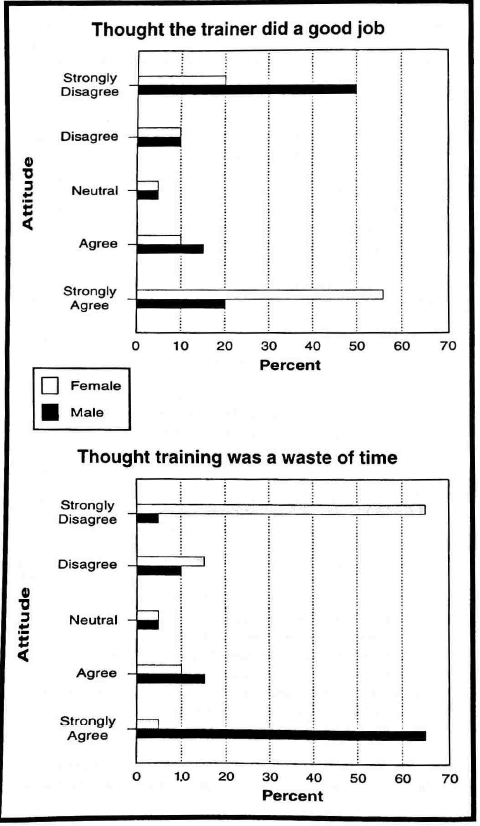

A key difference between the needs assessment and the needs assessment proposal is that we have completed the assessment. Now we have actual results to present in one section of the paper. If we presented employees with an attitude survey, we would present the results of the attitude survey at this point in the document. This might be a description of all the questions with a breakdown of the employees by area, or some other demographic characteristic. Exhibit 5.3 presents a typical page of results produced from a needs assessment. This is hypothetical and does not represent any particular organization. As you can see from the exhibit, we have taken two attitude items and looked at the results from a gender perspective. We could look at age, area of employment, and length of employment just as easily as the gender view. We must decide what ways we want to look at the data collected and present all of the information. In the results section we do not draw conclusions, just present the facts. We would note that a greater percentage of the females valued training than the males. In the next section, we describe what the result means in terms of any conclusions we might want to draw. It is in the conclusion section of our needs assessment that we can tell management what we would recommend based on the conclusions. For example, we might tell management that they have a problem with males in terms of training and that they need to demonstrate the value of training. In another example, we might have found that the attitudes of employees were very low with regard to communication within the organization. We might recommend on the basis of the attitude items that communication be improved. We would draw similar conclusions in other areas of our results so that management would have a clear picture of what the results mean.

We should incorporate alternative explanations for our results if we discover through the assessment that the results may be due to more than just employee attitudes. For example, we might know from interviews that some employees are unhappy with their salary and are negative toward the company, organizational communication, and every other aspect of the company. To report only the negative attitude toward communication would not give a clear set of results. Assessors need to shed as much light as they can on the issues.

Finally, we make recommendations based on our findings in two specific areas. We would recommend. where appropriate, training for groups of individuals in the corporation. We may, for example, recommend as a result of our employee attitude survey that all managers be given training in how to involve employees in participative management. We want to recommend categories of training in the needs assessment without listing each and every training topic.

Many times the results of our surveys and assessments prove that training may not be necessary, but that there are some recommendations that could be made in non-training areas. For example, we might find that a number of employees have personality characteristics and/or values that would suggest they don’t belong in people oriented jobs, but could do very well in other kinds of employment within the organization. This, then, would not be a training issue, but certainly could be a recommendation we would make to management regarding these employees. As we will discuss in later chapters, we do not want to overstep our competency by making recommendations when we are not qualified. We are not psychologists or counselors, so we limit our recommendations to areas of our expertise.

Thus, our needs assessment is a complete document, specifying the issues, the procedures, and the conclusions we would make relative to a specific audience and a specific assessment. We are now ready to present our document to our supervisor or contact person.

Exhibit 5.3 Attitudes toward training

Training Proposals

Once the needs assessment is made, we may want to incorporate a training proposal in the document or develop a separate training proposal based on the needs assessment. If we choose the latter approach, we would want to develop a document following the outline in Exhibit 5.4. You will recall an earlier example in which we talked about a proposal to do a needs assessment, but the company chose to do its own assessment and then turned to us for training. To follow up on that example, we were given the company’s needs-assessment document and the conclusions drawn from that assessment, and we were then asked to propose training on the basis of the needs assessment. In further interviews we developed the training proposal using the outline you see in Exhibit 5.4. We recommend this outline for any training proposal. Let’s examine the various categories within the training proposal in more detail.

As with the other two types of proposals, we are firmly convinced that an executive summary provides an excellent overview, as well as a persuasive mini document to convince the decisionmakers of the need for the training. When time does not permit a full review of the entire document, the executive summary contains a cogent synopsis of what is being proposed.

All of the other topics outlined in Exhibit 5.4 do not necessarily have to be presented in that specific order. We recommend that a trainer put them in the order appropriate for the organization.

Exhibit 5.4 Training Proposal Worksheet

| Executive Summary Target Audience for Training Title of Program Length of Program(s) Number of Sessions Objectives for Each Session Teaching Strategies Teaching Material Audiovisual Equipment Evaluation Plan Proposed Follow-up |

When making a proposal to do training, you are guided by any needs assessment previously conducted by you or others and by your conversations with the person who will hire you to do the training (decision-maker). One hiring agent may want your proposal to stress goals and objectives and may not care about a/v materials. Adapting your training proposal to meet the needs found in the assessment and to reflect the views of the decision-maker are your guides for ordering the proposal.

At some point in the document there should be a discussion of the trainees: who they are, and the purpose for their attending the training program. It should go beyond simply stating all managers at the supervisory level or above are the trainees. There should be a discussion as to why these people need the training we are proposing. We want to anticipate questions like “Why all managers?” or “Why only the employees?”

Certainly the title of a program would be optional, although selecting the title may help motivate employees. If the title indicates that participants will be in a training program on participative management practices. they may not be as motivated as if they are going to be put in a participative interactive management (PIM) program (of course, you’d better define the Jargon). It says the same thing, but may offer a little more pizzazz. The title, as well as the description, can be useful if the training programs are going to be voluntary rather than mandatory. Can you imagine employees giving up a day off to attend an all-day seminar on Affirmative Action regulations? They might, however, come to a session on “Avoiding lawsuits; hiring and firing with new Affirmative Action guidelines.”

The next two sections should incorporate the length of the program, as well as the number of sessions to accommodate the training. You may determine on the basis of your needs assessment and your program design that you need approximately twelve hours to develop a sound, listening-skills training package. Thus, the length has been determined, but you need to decide how the segments are going to be presented and the number of sessions. Would it be better to break up the twelve hours into two six-hour segments, four three-hour sessions, or three four-hour sessions? The resolution of these questions depends in a large measure on the content of the program, as well as the work schedules of the target participants in the training program. It may not be feasible to establish two six-hour training programs, but it might be feasible to offer four three-hour sessions spread over a 3-month period that the trainees can adapt their own work schedules to the train! program.

We believe that the proposal should include objectives for real training session, as well as a brief narrative of what will be covered within the session. We are not proposing that a complete description of the entire course and lesson plans be developed for your training proposal. The proposal should only give the manager enough information to decide whether it meets the needs assessment that has been conducted on the organization. Later, you will want to develop the complete program to ensure more effective training.

The next two sections talk about the strategies and materials that will be used for the training program. In other words, many managers want to know what teaching strategies will be used. For example, will the trainer offer a lot of participation or more of a straight lecture-discussion approach? From our discussion in chapter 3 of the adult learner, our bias on this issue leans heavily toward participation. What we’re doing is giving the manager or decision-maker enough information to decide that this training is something which should be delivered.

Some discussion should be included of what audiovisual equipment will be necessary for two reasons. First. is such equipment available in the organization? Second, spelling out the audiovisual needs will give the decision-maker further information on the teaching strategy to be incorporated by trainers.

No other portion of a training proposal is as important as the evaluation plan. In Chapter 9, we will discuss fully how one can go about evaluating the training program, but we need to underscore here that any training program should describe what evaluation will be used and how it will occur. Will the evaluation simply be a reaction to the training at the end of the sessions. or will there be some kind of on-the-job assessment of the training as it relates to employee participation and productivity? It’s important that the evaluation plan be spelled out. particularly if it’s going to occur long after the training program has been completed.

The final section, which is really a part of the evaluation, includes plans for a follow-up. Many times, managers and decision-makers balk at the training that is provided because it is like a shot in the arm: it helps for a while, but if there is no follow-up it has little lasting value. If we can incorporate some kind of follow-up to show that the training not only will be integrated. but also will be assessed periodically over six to twelve months, there is a greater likelihood that the training can be conducted.

We have thus described the type of training proposal that ought to be done whether you are an in-house trainer or an outside consultant. As we have suggested with the other two proposals, the training proposal is of greater importance for the outside consultant than it might be for the in-house trainer. It’s a good exercise for the in-house trainer to develop such a proposal even though the decision may be made inside the training unit. This proposal becomes a viable way of assessing the effectiveness of a training program within an organization by having it on file, even though approval may not be necessary from corporate management.

Presenting Proposals

We have described, then, three basic types of proposals that a trainer has to make on the job. We would like to talk a little bit about some of the characteristics of presenting the proposals without going into a complete discussion of written style or how to make oral presentations. We will touch on who the audience might be, how the proposals might be presented. and what the content might be.

Who should hear or read the training proposal? If you are working inside the organization, your immediate supervisor may be the appropriate audience for any of the three proposals. Sometimes this will be the vice-president of human resources or you may report directly to the president or CEO. If you are an outside consultant. The person who should receive the proposal is the one who requested you submit the proposal in the first place.

The reason this is a significant issue is that many times we do proposals only to discover that one of the problems within the organization is the very person who has requested the proposal in the first place. We have an ethical obligation to return the report with recommendations to the person who requested it, rather than to go over the head of that individual, either to a higher level of management or to a board of directors. If, in fact, the manager who requested the proposal is ineffective, that is something that person’s supervisor will have to discover and deal with, rather than using our report as a basis for such information. We are presenting our proposal to the person who requested it, rather than someone we personally might think would benefit most from it. That’s not to say that the person who requests it might not want us to give the proposal in written or oral form to others. In essence, we are saying that the proprietary rights of the assessment or proposal belong to the person who requested it.

For example, you may be asked by a corporate CEO to assess his or her organization. After interviews with employees, clients, managers, and the board of directors, you discover the CEO is a problem. You must still give your report to the CEO. If you are on good terms with the CEO, you can direct pointed issues to him or her.

Should the report be in oral or written form? Here there is no right or wrong answer, but only what is appropriate. If a written report is requested (or not rejected), it probably should be put in writing, even if an oral report is made in the first place. We are convinced that an oral report can be very effective but, like the executive summary, a written report is something that our manager or hiring agent could go back and look at in order to make final decisions. So, what are we saying? We are saying make the oral report only if that is what management has requested. If the door is left open, then certainly do an oral report followed by a written proposal like the ones we have suggested in the three different outlines. We can be very effective orally, but a written report provides good follow-up.

How should the reports be structured? We have offered sample structures for the three different types of reports. These are not cast in concrete, but are suggestions as you begin to develop proposals. They seem to be fairly standard and cover the essential information that would be requested by management or a decision-maker, in the case of an outside consultant.

The final question we need to consider is, what should the content of the various proposals be? We’ve tried to stress all along that when we make proposals, we keep the specific information limited. We do not believe that you should reveal all of your attitude items, for example, in a proposal to do a needs assessment, or all of the sampling procedures in great detail. Perhaps we’re being somewhat paranoid here, but we are convinced that if it’s your proposal it ought to remain as such and not be something done for others so that they might then go ahead and do the work without you. This is probably a bigger problem for the outside consultant, because we know of a number of cases where organizations have requested proposals only to decide that they would do the needs assessment and/or training in-house, and then incorporated what was submitted as proposals by outside bidding agencies. Certainly, this is not ethical, but it would appear to be a practice used by some organizations. Therefore, it’s essential, whether you are working in-house or are earning a fee for service, that you provide enough information to get the proposal accepted, but not so much information that the proposal could stand alone without your specific help.

In the needs assessment, we are convinced that you should provide as much information as you possibly can. keeping in mind the issues we described in chapter 4 with regard to the confidentiality of the people who are interviewed or surveyed. You have an obligation to avoid revealing the identity of individuals if the descriptions of their job titles would, in fact, reveal who they are. For example, if there are three employees within a division, each one varying in age by 20 years and by number of years within the organization, it wouldn’t take very long for someone to figure out who the three individuals were and what their opinions are. Certainly, you would be violating their confidentiality in providing that kind of detail. It is important in the needs assessment that the reader understand the basis for any results and conclusions you might draw. While we have yet to discuss ethics, we do want to be careful in how we draw conclusions based on our needs assessment findings. It’s very easy to say that the employees of X division were unanimous in their dislike for a particular employment practice, only to discover that only three of the ten employees filled out the questionnaire. This kind of information would certainly bias the results and conclusions we could draw.

Summary

What we have tried to do in this chapter is to spell out for you the types of proposals that trainers are often called upon to make, as well as to describe how you might present a needs assessment. We have talked about the proposal to do a needs assessment, the needs assessment, and the training proposal. We’ve also talked about who you should address your proposal to and the format in which the proposal ought to be presented. In the next chapter, we will talk specifically about how to design the training program that you have discovered was needed on the basis of your needs assessment.