Chapter 4, Doing a Needs Assessment

Objectives

This chapter will help you

► understand the purposes of a needs assessment

► recognize the components of a needs assessment

► identify the procedures involved in a needs assessment

► recognize the nature of the audience of a needs assessment

Introduction

The first step in effective training and development is to find out what the organization and employees need. As earlier chapters have pointed out, the nature of these needs is not self-evident. This chapter presents various ways of conducting a needs assessment, which is the process of identifying issues to be addressed in an organization.

Purposes of Needs Assessment

If employees knew exactly what they needed to learn, they could request certain kinds of training, learn those skills, apply the knowledge on the job and then work “Happily ever after.” If managers could identify their own and their employees learning needs, they too would work in an ideal environment. The reality. however, is that problems at work are expressed indirectly. Poor performance, low morale. and a host of other job-related problems are symptoms. and they cannot be taken only at face value. Individuals and teams may know that something is wrong, but usually are not able to identify exactly what that is.

There are many reasons why employees and managers have trouble identifying the real nature of problems. One is that they are, in a sense, too close to the problem. They know what is wrong in terms of how it affects them, but they do not see the problem in relation to the whole company. Take, for example, Jake, whose job is to deal with customers over the phone. Suppose Jake begins to hear nothing but complaints from customers who call in. From his perspective, Jake may conclude, “The customers sure are grumpy these days. They all need lessons in courtesy.” He logically may blame several things for the complaints: customers are dissatisfied with the product; the weather has adverse effects on people’s moods; or there’s too much bad news in the media. Because his perspective is limited to the scope of his job, Jake is likely to be unaware of company-related circumstances that might cause customer dissatisfaction — for example, a recent decision by the accounting department to pressure customers to pay more quickly, or a new marketing program that makes promises beyond the true capacities of the product. The point is that because Jake’s view is not broad enough. he is unaware of other organizational circumstances that affect customers and therefore have a direct impact on his job.

Another reason it is hard to identify the real problem is that so many possible interpretations exist. Everyone has his or her own ideas about why things go well, or do not go well, and what should be done about it. At work, every person’s performance affects every one else’s, no matter how indirectly. To really address the issue, an organization must synthesize various points of view to get a more complete picture of the problem.

A needs analysis is the process of getting as many views as feasible within the constraints of time, money, and the scope of the problem. The first purpose of the needs assessment, then, is to gather relevant data to help define the problem. When the views are collected, through the various means discussed in this chapter, the organization has a clearer picture of what is going on. In this sense, the needs assessment is a diagnosis of the organization’s health.

A second purpose of the needs analysis is to provide a background for alternative solutions to the problem. In the process of collecting data- that is, information about symptoms of the problem-the trainer can get a sense of what solutions individual managers and employees think would be appropriate. For example, Jake, dealing with customers over the phone, may think that the “real” problem is marketing’s unrealistic promises, and that the solution is to have marketing stop their overreaching campaign. Tracey, who works in marketing. may think the “real” problem is that employees in customer service are rude to customers, and that the solution is to train the employees to explain, in more detail and with more enthusiasm, the features of the product. Brooke, in accounting, may think the “real” problem is the outdated billing system. and the solution is to buy a new billing program. By synthesizing these and other views, the trainer gains an idea of the kinds of solutions that might work.

A third purpose of the needs analysis is to create within the organization an atmosphere of support for training programs the company ultimately will provide. If the firm were simply to tell employees “This is what’s wrong. and this is how we are going to fix it,” strong resistance would be a natural reaction. Even if top management were right, employees would resent its top-down approach. Although this always has been true, it is even more apparent today, as employer organizations become increasingly more team oriented and less hierarchical. By conducting a needs analysis, which asks for input from individuals at all levels of the organization, the firm is telling all employees and managers — all members of the team — that their input matters. The inclusive, participative nature of the needs assessment tends to reduce the likelihood of resistance and increase the likelihood of support. If support exists throughout the organization, solutions such as training programs are more likely to be well received-and effective.

Components of the Needs Assessment

While every needs assessment has unique features to match those of the organization, eight issues to consider are common in all needs assessments.

Timing

The first component is the timing of the needs assessment. If employees are under pressure, for example, they may be too hurried or distracted to give full attention to questions being asked of them. Or, if top management has just announced a new policy, say, longer or shorter vacations, the employees’ comments may relate more to the immediate event than an overall picture of the work environment. Suppose you were asked to do a needs assessment immediately following the announced layoff of a thousand employees. How might other employees view the timing of your task? They may think you are “spying” or helping management decide who gets laid off. To get accurate information, the needs analysis must take place under conditions that are as close to “normal” as possible. However, continual change, downsizing, fear of layoffs, high stress and other negative factors are part of the “normal” environment in many workplaces today. Trainers, therefore, must distinguish between incident-related stress and the “normal” high-stress atmosphere.

Participation

The second component is participation. Should everyone in the organization be involved in the needs analysis? While this may be ideal, it is extremely costly in terms of both time and money. It also is not necessary, because random selection of employees probably provides views that represent the entire organization. Sometimes, only certain departments need to be involved. To be effective, a needs analysis must get information from the appropriate sources. In a construction company, for example, the owner was concerned about delays on one project. He checked with his foremen, they checked with their crews, yet no cause for the delays could be identified. After much wasted time and through a casual remark to his secretary, the owner learned the delay was caused by problems involving paperwork in the office. By focusing only on the field crews, the owner had overlooked important sources of information. It is important to identify all relevant departments, and to include appropriate and/or representative employees from those departments.

Confidentiality

A third component is the confidentiality of information that is gathered. Most commonly, needs analyses focus on the issues raised, and not on who raised what issues. The confidentiality of the sources of information allows individuals to speak more freely. It also helps them believe that management is trying to focus on the issues rather than spying on them. Trainers’ reputations follow them. This is true for both external consultants and internal trainers. Confidentiality may be harder for internal trainers to maintain, because they work daily with the same people, develop friendships and prefer certain individuals over others. Those who maintain confidentiality will find it easier to work with the same employees “next time,” and those who don’t, wont.

Selection of Issues

A fourth consideration is how to select the issues to be examined. For example, the company may preselect certain issues that will come under scrutiny; e.g., management may want to examine leadership, job satisfaction or compensation. Once the issues are chosen, the needs analysis will be aimed at learning about them. The opposite, or emergent, approach is to use general open-ended questions, such as “How are things going in the company (or agency)?,” to find out what issues emerge as important to employees.

Whether a needs analysis takes the preselected approach or the emergent approach depends on the organization’s intentions. The preselected approach provides answers to what top management wants to know: the emergent approach seeks to find out what employees think is important. Both approaches have advantages and disadvantages.

In the preselected approach, one advantage is that management is able to focus on what it wants to find out. Another advantage is that employees simply answer what is asked, without having to think of issues themselves; this may save time and money. A third advantage is that employees learn which issues are important to management. This approach also has disadvantages, however. First, employees may resent the fact that they have no input about which issues are important to the company, in which case management would be making things worse by asking any questions at all. Second, management’s questions may focus more on the symptoms than on the real problems, and the view may be too narrow to identify real issues. Third, because of either the resentment employees feel or the symptomatic nature of the issues, management may get distorted responses.

The emergent approach has the advantage of allowing employees to speak their minds and identify any issues they consider significant, thereby helping them feel included and important. A second advantage is that the issues identified are likely to be close to the real problems, at least from the employees’ points of view. A third advantage is that because they had input, employees are more likely to support programs based on emergent issues. A disadvantage of this method is that it is time-consuming to unearth issues from answers to open-ended questions. The answers are likely to be broad and long, requiring time to sort through. A second disadvantage is that because of the time involved, this method is costly. A third is the risk that employees may expect all the issues they’ve identified to be addressed. Because not all issues can be addressed — at least, not at one time — care must be taken to alert employees to this fact. Otherwise. their expectations will be unrealistically high and they will perceive any solutions as falling short.

Company Philosophy

The fifth component of a needs assessment is the degree to which the needs analysis is part of company philosophy. If a firm’s general management philosophy is to tell rather than ask, a needs assessment may cause resentment or, even worse, suspicion on the part of employees. If, however. the company continually asks for input from all levels, the needs assessment will be perceived as a natural or appropriate event. This is especially true today, as both companies and government agencies move more towards participative and even decision-making, teamwork.

Target Population

The sixth issue is the target population – those individuals, departments, levels, or other categories that are going to be included in the questioning process. The size of the group may effect the number of types of questions that can be asked.

For example, if you were doing a needs analysis in a restaurant that had ten employees. the group is small enough for you to include everyone. In a larger restaurant chain employing five hundred people, however, you probably would make random selections of representatives from each job type.

The area of specialization of a department may influence the kind of information that can be gathered. If you were interviewing engineers, for example, you could expect them to talk about the technical side of their work. When you interviewed the sales staff, however, you would be more likely to hear about personalities and stress.

Employees levels of sophistication also can affect the type of information you get. For example, experienced, computer-literate employees are likely to describe symptoms that relate to the system; employees who are unfamiliar with, or resistant to, computers are likely to describe symptoms that relate to their terminal, boss, customer. or department.

Specific Method

The seventh component is the specific method used to do a needs assessment. A variety of methods is presented in the next section. The important consideration, however, is that each method has its own impact on different groups. Methods must be chosen on the basis of what will be most effective for each group. For example, interviews might be appropriate for small groups, while questionnaires would be better for large ones.

Depth

The eighth component is the depth of the needs analysis, or how much personal and emotional commitment it draws from employees. The appropriate depth varies with each situation, but a general rule is to go “only as deep as you have to.” It is both ineffective and unprofessional to become more involved than necessary. As an example, one consultant we know did a needs assessment for a bottling firm. Instead of limiting his questions to the immediate issues- such as employees’ opinions about company morale and opportunities for advancement, he began asking whether any employees drank alcohol on the job. Because his questions were deeper than the situation called for, he created distrust, suspicion and fear among employees and was unable to finish the project.

These eight components give the trainer ways to identify appropriate methods for a needs assessment. The trainer is then ready to select a needs assessment procedure.

Procedure for Needs Assessments

The number of ways in which to conduct a needs assessment probably matches the number of individuals doing them. Key ways to do a needs assessment include interviews, questionnaires, sensing, polling, confrontation meetings, and observation.

Interviews

Our professional preference is to use the interview as the first step in the assessment process whenever possible. We would recommend that you interview everyone you can, from the top person down through the organization. This may not always be possible if you were invited into the company by a manager to look at a specific department. But try to get a total picture of the organization you are assessing.

Who and how many people should you interview? We make it a point to interview people at each level and division in the organization. If the organization is small (for example, fewer than 50 employees), we may be able to interview everyone. If there are more than fifty employees, we can select employees in such a way as to give us a good cross section of the company. Your contact person can provide you with an organizational chart that should assist you in selecting interviewees.

The interview provides us with useful information that we can incorporate in questionnaires we might use. In one assessment, we discovered in interviews that employees apparently were not aware of career training opportunities within the company, so we developed a series of questions on career development training.

The interview method provides a personal touch, with all its benefits and limitations. Questions may be structured — that is, aimed at getting yes or no or other specific answers — or unstructured – that is, open-ended enough to require employees to raise issues of concern to them. The following structured questions were part of an interview with engineers.

For what kinds of jobs do you write proposals?

What is the average length of your reports?

Do your reports follow a prescribed format. or do you choose your own?

The following unstructured questions were used in the interview with the engineers’ clients:

How effective are the proposals the engineers write?

In what areas do you think the engineers might need help?

How creative are the engineers’ proposals?

You can see that the interviewer will get a vivid picture by varying the types of questions used and comparing the answers from each point of view. Through this process. a sensitive interviewer can glean a great deal of information from nuances, nonverbal behavior, and a host of other communication patterns, in addition to the answers themselves.

The interview establishes a great deal of rapport between employees and the interviewer. This rapport can contribute to support for the needs assessment itself and for the new programs it brings about. A limitation of interviews, however, is that more personal and emotional information than is useful may emerge. For example, during interviews one of the authors conducted in a hospital, many employees vented frustrations about their spouses. While this problem was real to the employees, it related only indirectly to the organizational issues. It also was the kind of problem that should be addressed in personal counseling, rather than in organizational training.

The interview method requires a great deal of time. Another negative aspect is that the interviewer’s skills greatly influence the richness of the data collected. If more than one person does the interviews, responses may not be equivalent.

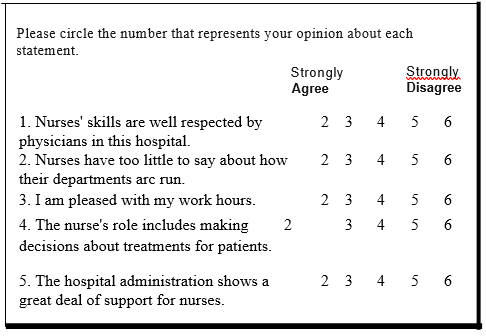

Questionnaires and Instruments

A questionnaire is the traditional method by which employees respond anonymously to a series of questions, While the questions could come after an emergent approach is used — that is. a questionnaire based on earlier input from employees — most deal with issues that are preselected. There are a variety of issues that you can address through questionnaire assessments. The primary purpose for questionnaires is to provide the trainer with employee perceptions of some aspect of the organization. Exhibit 4.1 contains a very generic questionnaire about nurses’ perceptions of their roles in a hospital environment. The questions cover topics from workload to credibility; none goes into depth on the issues. On the positive side, the questionnaire is brief and assures the nurses of anonymity.

Exhibit 4.1 Nurses’ Perceptions

At the other end of the continuum, some organizations ask employees to complete a ten- to fifteen-page survey on a regular basis. These surveys cover all aspects of the organization, from working conditions to career development. The success of lengthy questionnaires depends on management support and enthusiasm. If employees are asked every year for their opinions but the results are neither shared nor acted upon, employee cooperation will wane. In a survey for a high-tech firm, we distributed more than five hundred questionnaires to the hourly employees and received twenty completed ones. The time the company wanted the surveys distributed coincided with media reports of the plant’s closing and a major holiday season. You can see several of our eight guidelines were violated in this assessment by the person who requested the analysis.

Questionnaires also can be designed to focus on specific issues within the organization. If interview information suggests that a topic is important, a questionnaire can be used to determine how widespread the concern is. Interviews in one local government agency led us to conclude that teamwork and cooperation were lacking. We asked the employees to respond to a series of questions concerning leadership, teamwork, and cooperation. We combined the interview data with the survey results and presented a series of recommendations for training in that area.

Four other factors should be considered as you develop questionnaires. First you do not have to develop every survey from scratch. There are a number of questionnaires that have been used by both trainers and researchers that could aid you in designing questions. The bibliography at the end of this book provides numerous examples of questionnaires, whose topics range from organizational culture to communication satisfaction. You may want to use pre existing questionnaires, so be sure they meet your needs and that you have made appropriate arrangements with the survey developer (who owns the copyright). It may be easy to use a generic questionnaire, but you must make sure it fits the organization you are assessing.

Most questionnaires are in the form of statements with which a respondent can agree or disagree. The sample questionnaire in Exhibit 4.1 is in this form, which we call Likert scales. Choices for responding to these statements allow for degrees of feeling, ranging from strongly agreeing to strongly disagreeing and including several choices in between. Other choices might range from very frequently to never. We recommend this format because it is easy for the respondent to understand and complete. We also recommend that you read one of the research methods texts for a more complete discussion of survey development (see Babbie, 1985).

Another issue is who and how many people should get your survey. Ideally it would be desirable to survey everyone in the organization, but this is not always practical. Survey everyone in organizations with fewer than fifty employees. With larger organizations, make certain you survey employees at each level and within each division. You must make certain that you don’t survey just one person at a level or department, for the results could be biased and the anonymity of the respondent would be lost. Beyond these guidelines, we try to get our questionnaires into the hands of as many employees as we can.

When you consider a questionnaire, be sure you plan for each audience. For example, if you are assessing a supermarket chain, you will want to get feedback from customers as well as from employees. In today’s customer-oriented company and government agency, clients and customers — external and internal — should be included, along with department employees, as respondents. When a department in one firm wanted to know how effectively it communicated, we surveyed all employees in the department, all the department’s clients within the firm, and all its external customers. Each departmental employee got feedback about how his or her communication was perceived by departmental coworkers, organizational clients, and external customers.

A final concern in the development of a survey is the use of open-ended questions. As in interviews, open-ended questions allow the respondent some freedom in giving you useful information. You might ask employees to describe what they like best about their jobs and what they like least. While open-ended questions are not easily coded for computer analysis, the information can be invaluable. In an assessment completed by our students, they found agreement between the interview data and the open-ended responses but nothing useful in the Likert-type items. Analysis of the Likert-type items indicated they were too generic and in some cases, internally inconsistent. The assessment was not lost, however, because the students used several sources of information.

Questionnaires are relatively inexpensive and therefore make it easier to get information from everyone in the company. They simplify the confidentiality of responses and provide anonymity, which probably increases the likelihood of honest answers. Questionnaires also lend themselves to statistical processing. On the negative side, questionnaires lack the personal touch and too often do not allow for employee input in terms of content.

Sensing

This method is the same as the interview method, except that a select number of employees participate. The interviewees may be employees who are dissatisfied with something, a group on whom a pilot program has been tested, or individuals with some other characteristic that distinguishes them from the rest of the firm. One positive outcome of the method is that management is exposed to diverse views. Another is that programs may be designed for specific groups. One limitation is that this method may be perceived by employees as spying. Another limitation is that the effectiveness of the method depends on both the groups’ willingness to be honest and the interviewer’s skills.

Polling

Through this method, a group surveys its members to find out how people feel or think about current issues: Do we have too many meetings? How much influence on the company do I feel I have? How quickly and how well does management share its decisions? As an example, your boss might chat with each employee one day, asking, “How do you feel about the parking arrangements?” or “What would you think of us holding weekly staff meetings?” This method works best in groups of five to thirty. The benefits are that polling is fast and includes the entire group. A limitation is that the questions are not designed professionally and may not be useful outside of a specific group.

Confrontation Meetings

The confrontation is one in which individuals involved in a problem meet to discuss the problem openly. Generally, this kind of meeting cannot take place as a first step; rather, it follows preliminary work that includes individual interviews with the participants. The individual talks help create trust and support, both of which are required for effective confrontation meetings. A benefit of this method is that participative and gives everyone a chance to raise issues, learn others’ views, and share ideas. A limitation is that a great deal of skill is required on the part of the facilitator to neutralize potentially explosive situations and to create an atmosphere in which people will communicate openly and calmly.

Observation

Management by Walking Around (Peters & Waterman, 1982) is a fine way to do a needs assessment. If a manager’s regular behavior includes talking and visiting with employees, the manager gets a firsthand view of how things are going. By doing this regularly, the manager gains trust from the employees and is less likely to be seen as spying than is a manager who only shows up occasionally. These general procedures comprise needs assessment methods. It is important to remember that each organization is unique, and that every method must be adapted to fit the situation.

Audience for Needs Assessments

Even before needs assessment begins, the trainer must recognize who the audience is going to be. Everyone within an organization is a potential member of the audience. Depending on the situation, an individual may have a number of different roles: part of the target population during the needs assessment, a member of the audience when the assessment is complete, and a participant in training programs that follow the assessment.

Top Management

Top management is an audience that wants to know the needs to be addressed for greater company effectiveness. Top management’s concerns involve the long-term success of the firm. If employees needs go unmet, the results are poor performance, low quality work output, and dissatisfied customers or clients. If needs are met, the results are often good performance quality of work, and satisfied customers or clients. Because top management’s planning affects the future of the company, the managers must know what needs exist and then plan ways to meet these needs.

Top management has its own views and goals, and these must be included in the needs assessment. For example, suppose top management believes in promoting new managers from within, instead of hiring them from outside. One focus of any needs assessment within such a company would include ways of identifying the needs of employees who have the potential for. and interest in, becoming managers.

Managers

Individual managers within the organization comprise another part of the audience. These managers are responsible for the immediate performance of their employees, so they, too, want to know what needs must be met. In addition, managers have their own ideas about what needs exist for themselves and for their employees, so their views must be considered. As an example. the manager of a fast-food restaurant has many part-time employees whose jobs involve dealing with the public. The manager probably would want the needs assessment to include ways of finding out the strengths and weaknesses of his or her employees’ consumer-relations skills. At the same time, the manager would make sure the trainer conducted the needs assessment at various times of day, so all appropriate part-time help could be included.

Team Leaders

Team leaders make up another segment of the audience. Their roles are ambiguous, they guide and represent their work teams, but they do not have the authority of supervisors or managers. Team leaders rely on participation, cooperation, feedback, cross-training, and numerous other methods of continually improving team performance. They want input from internal customers (such as managers, other departments, and other teams), external customers (the final users of their products or services), and each other. As an example, computer services installs computers for the firm’s sales department. The sales department is an internal client of computer services. Customers who buy products through the sales department are external customers-not only of the sales department, but also of computer services. If the sales department’s computers are reliable, the external customers benefit because they can order any time they want to; if the sales department’s computers are down a lot. the external customer is inconvenienced. In this situation, the team leader within computer services is likely to want the needs assessment to include input from external customers as well as from the sales department.

Employees

Employees at all levels are an audience. They know the details of their work and many of the company programs are aimed at them. The accuracy of their input is crucial to the success of the needs assessment as is their acceptance of the results. Suppose, for example, the desk clerks in a hotel are told to take

a course in first aid. Their first reaction may be “Why?” because they do not see an immediate need. Even if they finally agree, they may resist management’s method of forcing this course on them. In this example, the main problem is that the employees know nothing about needs identified through an assessment process. Instead, they are simply told to take a course. Had the trainer recognized them as an audience, however, the clerks would have been included at the start of the needs assessment, and through their involvement in the data-gathering process, the clerks would have become aware of, and more receptive to, identified needs. When employees are included from the beginning of the process, they are more open to the results.

Trainers

The trainer is a special audience for the needs assessment. It is the trainer’s role to design the assessment in ways that produce legitimate identification of needs. The trainer’s role also means using this information effectively: designing programs that meet identified needs.

Knowing that he or she will design programs on the basis of the needs assessment, the trainer must make sure the assessment provides information both of the right type and in a useful form. For example. a consultant was called in by an electronics firm to help a trainer. Steve, design a needs assessment. Steve was looking for specific information: What kind of training in communication did employees need? He had planned to ask employees directly: “How much do you know about the communication process?”, “What areas of communication are you weak in?” , and similar questions. This plan would have resulted in useless types of information based on individuals’ self-perceptions of their communication skill, rather than uniform or shared definitions of communication. Steve also would have gotten this information in a form he could not use: personal opinions with no common scale of measurement.

The approach actually taken was to break communication into specific behavioral definitions. In this case, management turned out to be interested in public-speaking skills. Next, Steve identified ways of measuring the degree of a person’s success in this skill. As criteria he used audience evaluations and top management’s ratings of speakers. He then grouped speakers as excellent, average, or poor. Interviewing representatives randomly selected from each group. Steve asked questions that called for short, simple answers: “How much time do you spend rehearsing a speech?’. ”Do you use note cards or read from typed pages?”, and so forth.

Steve got information of the right type: in this case, answers about each speaker’s preparation and style. He also got the information in a useful form: answers that were either yes-no or numerical in terms of length of time. Because of their type and form. the data could now be compared and interpreted. By seeing themselves as part of the audience, trainers are better able to design needs assessments in ways that are useful to them.

Customers and Clients

Customers and clients also are audiences for needs assessments because they receive the final result of training programs: the actual products or services they get from an organization. They also are the reason for the organization’s existence. In the past, customers and clients were not involved in needs assessments because they were not directly involved with the company’s day-to-day activities. However, today’s focus on customer orientation emphasizes the importance of including customers in needs assessments. Because they are the “ultimate decision-makers ” about the value of the products , services, and the company or agency, customer/client input is extremely valuable.

When changes occur in a firm, customers and clients usually know this quickly. Whether changes are for better or worse depends, to a great extent, on training, which, in turn, depends on the accuracy and usefulness of a needs assessment. Take, for example, a drugstore where the cashiers are unfriendly. Customers may be attracted to the store because of convenience or low prices.

Some potential customers may avoid the store, despite convenience or prices, because of the unfriendliness. If a needs assessment were done in the store, and if it included customer input, one result might be interpersonal skills training for the cashiers. If the training were effective, customers would quickly notice the change.

Changes in management, in policies, or in other areas can have a negative effect on employees who otherwise are content. These changes, too, are quickly noticed by customers. The job of the trainer is to include customers’ views in the needs assessment, and to make sure the outcome will have a positive effect on them. The effect on customers determines, ultimately. the success of the firm.

Summary

Needs assessments affect everyone in the organization, and indirectly affect everyone outside of it who deals with the organization. Useful needs assessments are based on specific purposes, have key components, follow certain procedures, and are aimed at various audiences. Purposes include defining a problem, providing a background for solutions, and creating support for training programs. Key components are made up of timing, participants, confidentiality issue selection (preselected or emergent), company philosophy, target population, specific method, and depth of analysis. Interviews, questionnaires, sensing, polls, meetings, and observation make up the methods for a needs assessment, while the audience includes managers, team leaders, employees, the trainers themselves, and customers. As a basis for training programs, needs assessments serve as a diagnosis of what an organization needs to do to improve its effectiveness.