Chapter 1, Introduction

This chapter will help you

► understand training and development in the field of communication

► recognize important characteristics of communication

► distinguish between training and development

► identify ways to use training and development within organizations

Why Is Training and Development a Field of Communication?

If you want a career in training, this book will serve as an intro duction to the field. If your career goal is to become a manager, the points discussed in this book will help you develop successful ways of dealing with employees. If you are not yet certain about your career goals, this book will give you ideas to consider. The focus of the book is on the practical application at work of many concepts you learn in college.

The training and development field—T & D—has its own methods, literature, jargon, practitioner journals, societies, research, and folk-lore, as do all professions. An organization’s productivity and success depend a lot on the nature and quality of its T & D. Everything about an employee’s behavior-job performance, productivity, morale, turnover, absenteeism, teamwork, dedication, growth, commitment, career development, and related issues—is affected by the company’s T & D efforts. Companies of all sizes use internal training, public workshops, outside consultants, traditional and nontraditional college courses, and other resources to train and develop their employees. Many large companies have entire departments responsible for T & D. An organization’s T & D program serves as a visible indicator of management philosophy at work.

Whether it is done well or poorly, superficially or thoroughly, some kind of T & D exists in all companies and organizations.

Because of the variety of types of companies and organizations, T & D takes many forms. Sometimes it is done in a casual, haphazard way: for example, an employee may be expected to figure out the work by watching and listening to others who have the same job. At other times, the T&D may be formal, requiring employees to take courses related to new equipment or procedures. Many companies offer continuing training programs that employees may take voluntarily, and other firms require specific training of their employees. Occasionally, T&D covers personal, as well as work-related subjects. For example, a workshop dealing with listening skills may include ways to get along at home as well as at work. Companies also may offer courses in such topics as personal finances or physical fitness. Whatever the style, T&D most often focuses on the specific work at hand. In one restaurant, a new server may be told simply to copy what the other servers do. In another restaurant, he may go through extensive training that covers serving wine, pronouncing French names, and choosing formal clothes.

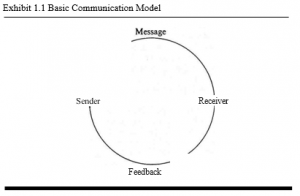

When we talk about communication training and development we address — the single common thread that crosses boundaries between organizations and job needs: the ability to communicate effectively. According to research findings, a basic communication model is as diagrammed in Exhibit 1.1. The sender is the person speaking or otherwise delivering a message, and the receiver is the person who reads, hears, or otherwise gets the message. Feedback is the receiver’s response, which may be in the form of words, facial expressions, or actions. Communication T & D focuses on helping people in organizations learn how to communicate with each other. At first glance, you may be surprised about this need. You may ask, “Why do people have to learn this at work? Don’t they already know this?” Unfortunately, the answer is often a resounding “No.”

Organizations are fraught with communication problems. which at times deal directly with the work at hand. For example, how do you explain a job clearly and thoroughly without overwhelming a new employee with details? If you focus only on the details of a job, the employee may not understand why certain steps are important. On the other hand, if you give “the big-picture” to a new employee too soon, he or she may have trouble understanding the boundaries of the job. As an example, consider the job of cashier. One new cashier may need to learn how to use the computerized cash register before learning anything else. Another new cashier may want to learn about the whole department and its policies before learning details about the computer. Through communication training and development, managers learn how to organize and pace information for new employees.

Managers need to understand various ways different employees learn; for instance, what is the best way to teach someone how to use a complex piece of machinery? Some people want only hands on experience. while others like to read technical descriptions first. Another problem is how to define job duties that are not easily measurable. For example, suppose the job of hotel clerk requires that employees behave in a “businesslike manner.” One person’s definition of ” business like ” may be very different from another’s.

Managers must be able to translate these kinds of job duties into specific behaviors. Other times, communication problems involve the future. How do you evaluate an employee’s performance in ways that motivate that person? Many managers are uncomfortable telling employees that their work needs improvement. and many employees have trouble hearing this. Managers often take good performance for granted, leading employees to feel that their good work is over looked. Communication T & D helps both managers and employees give and take feedback.

Communication T & D also can help managers increase employee morale. Through improved communication skills. managers learn ways to find out what employees need; for example, they might need to be trained in better listening skills. Often, the problems appear to be simple: Didn’t the employee get the message that our meeting was rescheduled? Is this report due tomorrow or next week? Which tool did the supervisor say I should use on this equipment? As the basis of our relationships with others. communication often is at the heart of an organization’s successes and its problems. Communication T & D shows trainers how to help people communicate more effectively.

What Is Communication?

Communication, like T & D, is a field in itself. This book focuses not on specific communication areas but on applications of communication methods, and it presents ways to train individuals and to help them develop their communication skills. Nevertheless, we must start with shared definitions, to be sure we are working toward common goals. Our definitions of communication are listed in the following sections.

What Is Understood Matches What Was Intended

Many people think communication is simply the process of sending out information. Instead, communication is the process of being understood. If the listener understands something different from what is meant, communication has not taken place, miscommunication has. Effective communication means that what is understood matches what was intended.

Roles, Relationships, and Objectives Are Clear

If communication has taken place, individuals understand what roles they play, how their roles relate to each other’s, and what functions everyone serves in the overall organization. “Roles” at work are the jobs people are to perform. The relationships among individuals’ roles are important, because each person’s job affects others’ work. Objectives often become problems at work because so many types and levels of objectives exist. The objectives of the firm, of each department, and of individual employees may differ from or even conflict with each other. Let’s use a manufacturing firm as an example. One goal of the marketing department is to sell as much product as it can, while a goal of the production department is to make quality products at low cost. Conflicts between these two departments often arise when marketing says customers want certain changes in the product, but production says the changes would be too costly. To accomplish anything, these different objectives must be worked out and meshed. Because nothing ever stands still, the process of clarifying roles, relationships, and objectives is ongoing.

Thoughts, Feelings, and Attitudes Are Expressed

When group members are open about what they think and feel, the group develops trust, understanding, and the ability to work things out for everyone’s benefit. Hiding the inner self—that is, refusing to communicate—works against the effectiveness of groups and relationships. Yet many individuals find it difficult to be honest about what they think or feel. Sometimes they are wise to hold back, because the environment does not allow for openness. For example, do you always tell your best friend only the truth? At work, a manager’s gruffness and unapproachable management style may discourage employees from giving honest feedback. Other times, people hold back unnecessarily because of their own personal fears.

The problem is that the success of a group depends on the degree of honesty each member can give and receive. In a group that communicates well, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes are expressed. This is especially true today, because teams and teamwork are more common and more important than ever. Honesty, in a kind manner, is important to successful teamwork.

Specific Wants, Needs, and Instructions Are Identified

In addition to expressing your views honestly. it’s also Important to specify what you want others to do. Vague descriptions or the hope that others will read your mind are doomed to failure. Many of us. however. operate this way without realizing it. We assume that our own perceptions of the world are self-evident to others. and that therefore others will know exactly what we mean or what we need. This assumption ignores the fact that people have their own sense of reality. and that we all have different ideas about what any situation calls for. Communication involves making your expectations clear to others

Process, Rather than Content, Is Emphasized

Content means what people say, and process means how they say it. Often, the content and process of a statement contradict each other. Suppose a manager says. “I’m interested in hearing about your problem.” The content level of this statement is clear. To match the content level. the manager’s process would include such nonverbal clues as eye contact with the employee, a friendly and supportive tone of voice, a facial expression that shows concern and interest, and body posture that is open. If, however, the manager’s process is abrupt, defensive, angry, or closed, it will contradict the content. Research shows us that most people will believe the nonverbal message more than the verbal.

Very often in organizations and in relationships, people think they disagree in the content area when the problem is, in fact, on the process level. For example, two employees may have a conflict about the best way to get a job done, when the real problem is that their boss encourages competition rather than cooperation. In this case, the best way to get a job done is not really the issue. The issue is that neither employee wants to agree with the other. Process— in this case, the way people relate to others, and what kinds of behaviors are rewarded—must be dealt with before the employees and the company can function well. The focus of communication is on how people relate to each other—what processes, cues, and other forms of interaction occur, and how they affect relationships and productivity—as well as on what is said.

Communication is all of these things and more. Despite what many people assume, and act on, communication does not just happen by itself. Instead, it takes a great deal of conscious effort, practice, and training. The natural order of things leads more often to miscommunication than to good communication. In organizations. nearly every problem can be traced to a communication problem; but this fact only adds to the confusion. because the subject is so broad. Communication T & D helps people at the process level (things they can do to communicate effectively) so they can better convey the content they wish to deliver.

What Is Training and Development?

Although the two words often are used together, and although they both deal with improving human performance, the words “training” and “development ” represent two different emphases. Traditionally, training means teaching people things they need to know for their current jobs, while development means preparing them for the future.

Training

Training refers to teaching specific skills to individuals. These skills, required by the present job, include the following:

physical manipulations, such as running a machine

specific procedures, such as how to order new materials

company policy, such as supplying an employee with the name of a manager when a personal problem affects his or her work performance

specific behaviors, such as how to deal with customers over the telephone

specific methods, such as how to fill out grant applications

Training can take place any time during a person’s career. A new employee needs training to learn the specifics about the job and company policy. A long-term employee needs to learn how to use the new computer system. Workers need to develop supervisory skills so they can be promoted. New managers need to be trained to deal with specific problems they face in their new jobs. High-level managers need to learn additional skills, such as public speaking or business writing. Teams need team-building and team-maintenance skills. Training is a broad area that covers these and other job -related skills, and takes place on several levels.

Informational Level. The first is the informational level, where the purpose of training is to teach a person about something. Company policy, the importance of following procedures, or rules about work are examples of information that can be taught. Even skills, such as how to give effective presentations or how to use a computer, may be taught at the informational level. In these cases, the person learns thoughts and ideas about a topic, but does not have any physical or applied exposure to the topic. The goal of informational training is to increase trainees’ awareness of a topic. This book will give you informational training.

Behavioral Level. The second level of training is behavioral, which goes beyond thoughts and ideas and gets into specific ways to act or to perform tasks. If the topic were how to give presentations, trainees learning at the behavioral level would actually design, write, and give presentations to the group. If the topic were computers, trainees would actually sit down at computers and design or use programs. The goal of behavioral training is to teach trainees how to do something.

Results-oriented Level. The third level of learning is results oriented, where trainees’ learning is designed to have an effect on the organization. For example, managers who learn how to use performance-evaluation sessions as motivators of their employee may help decrease employee turnover in the company. Because organization-wide results are long term rather than immediately noticeable, they often are difficult to measure. Nevertheless, the goal of results-oriented training is to improve the productivity of an organization and to help determine its future.

Whether the training is informational, behavioral, or results oriented, it relates specifically to job skills employees need in order to do their work. Often, these skills result in effects that are long range or that go beyond the job. For example, a person may learn how to deal with angry customers (a behavioral skill) and this ability may change the way that person deals with people in the office, at home, and elsewhere. In a sense, the carry-over means that the training has gone in the direction of development, because the training is not limited to the person’s present job. Nevertheless, specific information, behaviors, methods, procedures, and physical manipulations comprise training.

Development

The development of a person includes, but does not stop at, training.

Development includes more conceptual understanding of the “why” and more cognitive recognition of how certain behaviors or skills fit into the wider context of the entire organization. Development involves a systems approach. In a systems approach, each persons’

job is seen not only as an activity in itself, but also as one part of the organizational plan. Beginning with self-awareness, individuals learn how they fit into the roles and relationships within the department and, later, with the entire organization. They also learn how others relate to this larger context.

Self-awareness is the key to individual development. Self-awareness begins with a realization of how you come across to others: how they interpret your behavior, regardless of your intentions. Often, people are surprised at the difference between how they see themselves and how others see them. The difference may be positive: others think more favorably about their behavior than the individual had expected, or others benefit more from the individual’s behavior than he or she realized. Or the difference may be negative, as when people think they manage in a participative way but their employees see them as narrow-minded dictators. As an example, an executive who was a client of ours had a companywide reputation for being cold, harsh. unpredictable, and indifferent to employees’ needs. He was aware of his reputation, but disagreed with it, believing himself to be very concerned about his employees and methodical in his methods. By disagreeing instead of listening, this executive cut off feedback and opportunities to learn from it.

Others’ reactions to you are a form of feedback, telling you how you come across. This kind of feedback is crucial to self-awareness, because it helps you learn what you actually do, how you affect others, and how effectively you carry out your intentions. When the feedback differs from your own expectations, it can help you change your behavior. The feedback may also alert you to unacknowledged needs you have or unacknowledged room for growth. Self-awareness begins the long process of individual development. The Johari Window, developed by Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham, represents various levels of self-awareness. The purpose of the Johari Window is to help individuals identify how much they know about their own behaviors. The “window” looks like the illustration in Exhibit 1.2. Box 1 represents things about ourselves that we and others know; for example, whether we are tall or short. In terms of our behavior, this area might include such things as our moodiness, our good sense of humor, or the types of people we like to date. Box 2 represents things we know about ourselves, but do not share with others. For some people, this area would include their political views, while for others it might be such things as their long-term goals, personal morals, or social lives. Box 3 represents things others know about us but of which we are unaware. For example, your friends, and not you, might know that you frown when you read or that you laugh when you are nervous. Box 4 represents a blind spot, where neither you nor others are aware of certain of your behaviors The Johari Window is not something you would draw literally and carry around with you. Instead, it is a model that can help you become aware of how you act and how you relate to others. As an example, suppose you got along well with all but one person in your social group, whom we’ll call John. You could use the Johari Window in the following way:

Exhibit 1.2 The Johari Window

The Johari Window

| Known to Others | Unknown to Others | |

| Known to Self | 1 | 2 |

| Unknown to Self | 3 | 4 |

First, in Box 1, identify what you share with John: what is known to him and to you about how you act toward him. This is a way of asking yourself how you look from John’s point of view.

Second, in Box 2, identify what you keep from John: what you know or do that John is unaware of. This is a way of finding out what John may not know about you. Would you get along any better with him if he knew some of this about you?

Third, in Box 3, put yourself in John’s place and try to imagine what he may know, see, or think about you that you are unaware of. Could your unawareness be hurting the relationship? Might John misunderstand you?

Fourth, the blind spot in Box 4 is not relevant because it involves issues that neither you nor John is aware of. So, based on your analysis of the first three boxes, are there things you could do to improve the relationship with John?

After a while, you may begin thinking this way automatically. The Johari Window is a useful model for increasing your self-awareness.

The process of self-awareness is continuing and disjointed. It occurs in large and small pieces and in unpredictable time frames. Moments of self-realization may take place spontaneously, often days, weeks. or months after a planned development activity. Because of the disorganized nature of individual development, the steps overlap instead of following a sequence.

Roles

Once self-awareness begins, you are ready to learn more about the ways people relate to each other. One aspect of relationships at work involves roles people play. A functional role is a summary of your job description: what you are responsible for at work. For example, an office manager’s functional role is to make sure the office runs smoothly; the functional role of an ironworker is to build a solid framework for a building. The behavioral role you play involves the way you interact with other people. It is predictable, consistent behavior that, over time, others come to expect from you. Your behavioral role has nothing to do with your intentions—that is, what you think you are doing. Instead. your behavioral role is what you actually do, and how your actions affect others. As an example, every office has someone whose behavioral role is the complainer—someone who will object no matter what the circumstances are. Other examples of common behavioral roles at work are the worrier, who predicts gloom and doom for any project; the optimist, who sees the good side despite bad news; the early bird, who considers a person late when that person is on time; and the gossip, who knows and spreads personal news about colleagues. We all have behavioral roles that describe our ways of interacting with others. Benne and Sheats (1948) identify the following categories of roles:

Group Task Roles

Initiator-contributor: starts discussions and begins changes

Information seeker: asks for clarification of facts

Opinion seeker: asks to clarify group’s values Information giver: offers “authoritative” information

Opinion giver: influences group’s values

Elaborator: uses examples, presents implications

Coordinator: pulls ideas together

Orienteer: summarizes what has gone on in discussion

Evaluator-critic: sets standards for group

Energizer: prods group into action

Procedural-technician: does tasks for the group

Recorder: keeps written records

Group Building and Maintenance Roles

Encourager: offers praise and warmth within Harmonizer: mediates differences in group Compromiser: establishes agreement in group

Gate-keeper: encourages participation from all Standard-setter: uses standards to guide action

Group-observer: Interprets group processes

Aggressor: “attacks ” group in various ways

Blocker: negatively resists group processes

Recognition-seeker: calls attention to self

Self-confessor: expresses nongroup-oriented ideas

Playboy-playgirl: flaunts a lack of involvement

Dominator: uses manipulation to gain authority

Help-seeker: seeks sympathy from group

Special-interest pleader: disguises own biases through representing special groups

Interestingly, our functional roles and behavioral roles do not necessarily predict each other. An employee may behave more like a leader than the manager does. A supervisor with a great deal of responsibility may act out the behavioral role of the forgetful one. In the area of individual development, behavioral roles are more important than functional roles. Behavioral roles describe our predictable behaviors, as others have come to expect from us. When we get feedback from others, we learn their perceptions of the behavioral roles we play. To repeat, we may be surprised when people describe us in terms of behavioral roles we did not realize we were playing. The surprise comes from the fact that our intentions often are different from the way our behaviors come across.

Recognition of our behavioral roles is crucial to development. Social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) describes the interaction among individuals, their behaviors, and their environments: all three affect each other equally. According to part of this theory, one’s behavior draws reactions from others and these reactions become part of one’s environment. That is, the ways others respond become part of one’s surroundings — an atmosphere of praise, criticism, encouragement. resentment, support, or an infinite number of other possibilities. For example, a manager may have a policy of praising employees whenever they suggest money-saving ideas. This manager’s response — praise — becomes part of the employees’ environment. In turn, the environment affects them and thus influences the way they behave. Because they know, for example that the manager praises money-saving ideas, the employees are likely to come up with these ideas frequently. Based on this part of social learning theory, the predictable nature of our behavioral roles draws predictable reactions from others. Getting to know people means becoming able to predict their behavioral roles: and as others’ behaviors become predictable to us, our behaviors in turn become familiar to them. The interaction among behavioral roles—each person’s behavior drawing predictable reactions from the others—means that we may influence others’ actions. Once we know the behavioral roles we tend to act out, we can better understand why people respond to us the way they do.

For example, an employee we’ll call Susan has had her job for six months. Susan’s boss has told her that her work is fine, so Susan feels comfortable about her ability to perform well on the job. However, she has noticed that on a social level, she has problems with several coworkers. Realizing that the informal system — that is, the social side — at work could affect her job security, Susan decides to analyze her interaction with her coworkers. Looking first at her own behaviors, Susan recognizes that her behavior at work includes reminding others about their deadlines. Susan means well; that is, her coworkers’ deadlines affect her own work. and her intention is to be helpful to them as well. In terms of her behavior, however, Susan realizes that she acts out the role of the “office nag.” Her behavioral role creates resentment among her coworkers because they perceive her as not giving them credit for managing their own workloads or schedules. Because of her behavioral role, and her coworkers’ resentment of this role, Susan has unwittingly invited negative reactions from others, which she did not intend. Once she realizes how her own behaviors draw negative behaviors from her coworkers, Susan is able to change the relationships. She watches her own work and time frames, and deals with her peers in the usual way except for one thing: she no longer refers to their deadlines. Instead, she leaves their time management up to them. At first, no one notices, because their expectations already have been established and people continue to perceive Susan in terms of her familiar behavioral role. Over time. however, her coworkers come to realize that Susan no longer nags them, and they begin reacting to her in a more relaxed way. Within a month, the relationships among Susan and her peers are much friendlier and more open than before. In terms of predictable roles, Susan’s change in behavior brings about different and more positive responses from her coworkers. This example shows how we can affect the way people respond to us, by recognizing and modifying our own predictable behavioral roles. Development includes this self-awareness and recognition of our behaviors.

In development, an individual also would learn how these behaviors fit into the broader picture: company needs, his or her own interests and goals, and other opportunities within the firm. Development increases individuals’ self-awareness, helping them discover how they relate to others, how their self-images compare to others’ perceptions of them, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. Development also deals with individuals’ long-term career goals, first by helping people learn what their skills, interests, and capabilities are. The next step is to help them identify their specific goals. For example, someone who is good in math may want to go into accounting, computer programming, engineering, or any number of other careers. Once the specific goal is identified by the manager and worker, the next step is to help individuals identify the training they need to reach these goals. Some people may want to go to college or enroll in graduate programs, while others need in-house courses or outside workshops. While training focuses on specific skills and behaviors, development aims at helping people achieve their full potential, both personally and professionally.

Training and development, as a field, emphasizes two different sides of one process. When the emphasis is development, the newly learned skills and behaviors affect individuals’ self-images, capabilities, and goals. When the emphasis is training, the person must learn specific behaviors and skills to do his or her job well.

Who Needs Communication Training and Development?

Everyone needs communication training and development. In all companies, nonprofit agencies, and other organizations, some people almost always are teaching others how to do the work, how to hire new employees, how to train new workers, how to improve work performance, how to give job evaluations, how to write memos, how to write proposals and reports, how to motivate others, how to get more productivity out of employees, how to deal with customers, how to get help for troubled workers, how to avoid or resolve conflicts, and an infinite number of other issues. Ironically, while many people may be qualified to teach the content of these issues, they are not necessarily skilled in the process of teaching them. The result often is poor learning and, therefore, poor performance due to ineffective communication.

Naturally, the first group of people who should learn communication training and development are those who hope to become trainers: the professionals whose work it is to teach employees within organizations. Sometimes, trainers learn about equipment, company policy, ways to discipline employees, and other content areas they will teach, without learning the processes of training. Partly because communication is a subject area in its own right, and mostly because communication is the system that helps or hinders organizations, all trainers need communication training and development. Another, larger group also needs communication T & D: the managers and supervisors who run organizations. They need to understand and know how to use the communication process, because they are the ones who determine the effectiveness of the company. It is from managers and supervisors that employees — and the managers themselves — learn “how we do things around here”: how we make decisions, what kinds of behaviors gain recognition, what it takes to get promoted, how teams can be effective, what quality of performance is expected, what the firm’s philosophy is, and numerous other subtleties. Managers and supervisors are also the ones who teach employees how to do specific jobs. Because communication is the basis of everything that goes on among people, everyone who teaches people needs to know how to communicate effectively.

A third group needing communication T & D is the employees themselves. In addition to teaching specific skills to each other, employees continually interact because their work overlaps. Misunderstandings, mistakes, physical dangers, poor work, hard feelings, high costs, and other negatives can result when coworkers have trouble communicating with each other. Working in teams requires constant communication. In addition, employees often feel frustrated because they would like to convey certain ideas to management but they do not feel comfortable doing so, usually because they do not know how. Communication T & D helps employees and, through them, the entire organization.

In fact, there is hardly anyone who does not need communication T & D. All of us have multiple roles, and all of us communicate with others in various ways and for various purposes. We all learn from one another. Each of us is a product of our relationships, as well as of our uniqueness. We affect each other. for better or for worse. Because our relationships depend on how well we communicate, we all need training and development.

Summary

Training and development is vital to all organizations. Training relates to employees’ specific needs for their current jobs, while development involves a system-wide approach to meeting individual career needs and organizational management needs. Communication training and development teaches trainers how to help people communicate more effectively. Because communication is such a crucial element in organizations, communication T & D serves an important function.