5 Navigating Courageous Conversations

Learning Objectives

- Articulate what can make conversations challenging

- Reflect on how your personal and social identities affect your response to conflict and develop greater self-awareness

- Evaluate techniques and strategies to help you and your students navigate challenging situations and courageous conversations

- Anticipate circumstances that could lead to a courageous conversation and make a plan for handling them effectively

What is a Courageous Conversation?

This is one example of a courageous conversation from the article On ‘Difficult’ Conversations By Derisa Grant[1]

Years ago, I taught at a predominantly white institution. During the final class, a student who identified as white, male, and upper middle class advocated removing poor children from their families and placing them in boarding schools. This conversation, initiated by a student holding dominant identities, could very well be described as difficult.

As an instructor, I was forced to confront a perspective different from my own —one that I was shocked to learn my student held and one that I personally found reprehensible. I felt stunned but given that the student had made the comment in front of 49 other students, I also felt pressured to immediately respond.

Therefore, to give the student an opportunity to hear how outrageous his statement was and to clarify, I repeated what he had said and asked if I had understood correctly. When the student affirmed his position, I then opened the conversation to all students and asked them to respond with reference to texts we’d read that semester on topics such as assimilation and culturally relevant pedagogy.

In the discussion, the class countered their peer’s position using literature. I wrapped up the discussion by thanking the student for surfacing the issue and by summarizing the key concerns that his peers had raised.

|

Reflect |

- Have you had similar situations arise in your classroom or learning space?

- How have you responded? What might you do differently if given the opportunity?

- What works/doesn’t work for you about the way the faculty in the example handled the difficult conversation?

Introduction Video

|

Throughout the module, we use this icon to suggest times to reflect on a concept, your professional practice, or yourself. We hope these questions help spark your thinking in new and creative directions. |

Reflecting on Identity

Reflecting on our identities and acknowledging how they manifest in our education practice is ongoing work. Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your own identities and how they relate to this module.

Consider your own personal learning about the topic. Where do you fall on the following continuum?

| I have not yet begun thinking about this |

I have started to learn more about this. |

I am actively thinking and learning about this. |

I am applying my new learningand remain committed to further reflection and growth. |

|---|---|---|---|

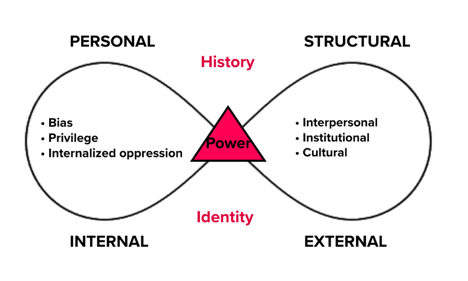

- In what ways does my social and geographical location influence my identity, knowledge, and accumulated wisdom? What knowledge am I missing?

- What privileges and power do I hold? In what ways do I exercise my power and privilege?

- Does my power and privilege show up in my work? If so, how?

- Am I aware of if/how my biases and privileges might take up space and silence others?

It’s important to realize that you do not have to be an expert on these topics to actively engage in self-reflection and conversations with students. Being an equity-centred educator requires regular and repeated reflection on the Eurocentric assumptions, knowledges, and ways of being that guide our thoughts and actions.

Being aware of which knowledges, experiences, and ways of being in the world are privileged in your discipline, classroom, and institution are a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is legitimate action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Unpacking Language: Key Terms

Words matter, and words can have multiple meanings.

In this section, you’ll engage with several important words and ideas related to power, privilege, and bias. We will only skim the surface of these important, complex, and deep-seated issues.

The purpose of this section is to establish a shared understanding and vocabulary to build on in future modules. This work is essential but is also sometimes uncomfortable. This should not deter us from doing it.

As a staff or faculty member, recognizing and addressing the meanings of these words in your planning and reflection is important. The more clearly a term is articulated, the more likely you are to develop the knowledge and skills to use it. You will also feel more comfortable talking about and using these words in your teaching and interaction with students.

Write

Take a couple of minutes to jot down your understanding of the following key terms (don’t worry about getting it right or perfect; the idea is to respond quickly):

- courageous conversation

- hot button moment

- supercharged topic

- brave and safer spaces

Review

Now, review the following definitions to see how your understanding of key terms aligns:

courageous conversation: Participants commit to engaging with each other and the group with honesty, vulnerability, and an open mind. The goal of a courageous conversation is to listen closely so we can understand each other’s perspectives, even if we don’t agree, and to keep the conversation going, even when it gets uncomfortable.[2]

hot button: These moments sneak up on us in the form of microaggressions, stereotypes, myths, personal attacks, generalizations, and the dominant narratives people bring with them into a conversation. Dominant narratives are stories told by the dominant culture to uphold and reinforce through repetition the dominant social group’s interests and ideologies. “Isms” like racism, ableism, and classism are rooted in these dominant narratives, which come to be accepted as objective truths. Hot button moments can provoke strong reactions and disagreements, and though we might not feel qualified to even take a position or have an opinion about some of these issues, we still need to do our best to facilitate a courageous conversation.

supercharged: Supercharged topics are the ones you know without a doubt will provoke debate and elicit strong emotional reactions. While these reliably controversial topics do require careful preparation, they have the advantage of being predictably difficult — so you can be ready to facilitate the conversation responsibly and effectively.

brave and safer spaces: In these spaces, we acknowledge, support, and learn from painful or difficult experiences, rather than eliminating or ignoring them. Brave and safer spaces ask us to engage in genuine and honest conversations about equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging. This involves the participation of the whole community — in this case, the group, class, or organization — in creating supportive spaces where people can be their full, authentic selves.

Approaching Courageous Conversations

Know yourself. Know your biases, know what will push your buttons and what will cause your mind to stop. Every one of us has areas in which we are vulnerable to strong feelings. Knowing what those areas are in advance can diminish the element of surprise. This self-knowledge can enable you to devise in advance strategies for managing yourself and the class when such a moment arises. You will have thought about what you need to do in order to enable your mind to work again.

– Lee Warren[3]

Remember: Facilitating courageous conversations is a skill. Like any skill, it takes practice and repetition. You will make mistakes and you will mess up, but you will also get better and find ways to help your students engage in courageous conversations more safely. There are many resources available online to help you build the skills and confidence to handle hot topics and critical conversations. Check out the Learn More section at the end of the module.

We don’t just do equity with students. A commitment to equity means we work to have courageous conversations with colleagues, family, and friends as well.

Why talk about courageous conversations?

Courageous conversations are an important part of higher education. It’s probably fair to say that we should welcome courageous conversations because they challenge us and help us learn! It’s also fair to say that these conversations can feel scary and sometimes we find ourselves in over our heads.

In any education setting, you’ll find students — and colleagues — with many different experiences, interests, knowledge, and even ways of knowing and making sense of the world. We welcome this diversity because it adds so much richness to learning experiences.

Sometimes policies, programming, course content, or on-campus activities can spark controversy or serious disagreement. When we’re passionate about something, it can be hard to listen to other perspectives, let alone understand them. Helping students learn to have respectful conversations when there is disagreement is important.

As faculty members or student services professionals, we have the privilege of guiding students in exploring emotionally or politically charged issues. Courageous conversations help all students — and us — grow personally and academically.

Approaching Courageous Conversations Step by Step

This series of videos will help you begin to develop skills and confidence to have courageous conversations. Remember that these skills evolve and grow over time, for everyone. Nobody is an expert, and there will be times when you feel uncomfortable, challenged, and like you don’t know what to do or say.

Being prepared for courageous conversations starts with laying the groundwork for students to engage in challenging discussions before those conversations happen.

Even in an environment that centres equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging, students will actively disagree and may become upset about statements made by their peers — or by instructors or student services staff.

Lay the Groundwork

Begin the conversation

After the conversation

Navigating Difficult Conversations in the Classroom

In this video, Dr. Tanya Sharpe and Dr. Geoff Greif, from The University of Maryland School of Social Work, discuss how to navigate challenging conversations in the classroom.

|

Reflect |

After watching the video, take a moment to reflect on the following questions:[4]

- Has a situation similar to this occurred in your classroom, lab, program, or office?

- How did you respond to the techniques used in the video?

- How do you see yourself using these techniques in your professional practice?

- How might have you responded differently?

Tianyuan Yu: Using the Council Practice or Talking Circle to hold space for all students.

Courageous Conversation Openers

Courageous Conversation Openers

- I’d like to talk about ______ with you, but first I’d like to get your point of view.

- I need your help with what happened. Do you have a few minutes to talk?

- I think we have different perceptions about __ ____. I’d like to hear your thinking on this.

- I’d like to talk about ________. I think we may have different ideas about how to ________.

Culture of Accountability: Brave and Safer Spaces

You’ve probably heard people describe classrooms, common areas, and offices as safe spaces. While the intention behind this idea is good, labelling an area a safe space can be misleading because we can’t guarantee that our educational environments will be free of danger, risk, or harm. The idea of the safe space can also excuse us from tackling difficult issues and doing the hard work required for deep learning.

Brave and safer spaces

Brave spaces, on the other hand, ask us to engage in genuine and honest conversations about equity, diversity, inclusion, social justice, and belonging. We can’t guarantee safety, but we can work toward safer spaces where everyone can be their full selves.

[C]reating brave spaces [can] challenge the implicit and explicit ways in which inclusion and exclusion, affirmation and disenfranchisement, and belonging and alienation play out for people with different identities.

– Alison Cook-Sather[5]

Read

To learn more about brave spaces, read Creating Brave Spaces Within and Through Student-Faculty Pedagogical Partnerships by Alison Cook-Sather in the Spring 2016 issue of Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education.

Jeffrey Dessource and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy. TEDx New Jersey City University.

Establishing Brave and Safer Spaces[6]

Establishing Brave and Safer Spaces[6]

- See conflict as neutral in a diverse group. It’s important to stay engaged through conflict.

- Own your own intentions and your impact.

- Challenge by choice. Encourage students to think about how their social identities influence whether and how deeply to engage in a challenging activity or dialogue.

- Don’t allow attacks. Describe the difference between a personal attack or an individual and a challenge to an individual’s idea or belief.

|

Reflect |

Think of a time you experienced a brave or safer space. This could be a brave space that was created either intentionally or not

- Reflect on what made the space brave. What did you see, hear, and feel? What did the facilitator do to create safety?

- What conversations and actions were made possible by the brave space?

- How can you imagine creating brave spaces in your professional practice?

Ideas for Being and Working Together[7]

There are many words to describe ways of being together and creating safer spaces for courageous conversations. Group agreements, ground rules, or Mawita’mk — “being together” in Mi’kmaq — are all ways to refer to guidelines we co-create with students for engaging with challenging topics. They can help us take part without excessive fear of being labeled racist or biased, avoid blaming, and avoid invalidating others’ experiences and feelings.

Stay engaged

- Focus fully on the conversation topic or exercise at hand

- Silence cell phones

- Share a story, state your opinion, ask a question—risk and grow!

Speak your truth

- Value everyone’s thoughts

- Start by assuming good intentions

- Speak from your own experience and use “I” statements, as in “I think”, “I feel”, “I believe”, or “I want”, “I hear”

- Create a safe environment where everyone is free to speak openly

- Keep in mind that people are in different places in this work

- Be aware of non-verbal communication

- Before speaking, think about what you want others to know

- Recognize mistakes are part of success

- Disagree respectfully

Listen for understanding

- Listen without thinking about how you are going to respond

- Try to understand where another person is coming from

- Be careful not to compare your experiences with another person’s

- Try not to explain or rationalize if someone points out that something you said left them feeling upset. Positive intent is not enough. Say, “I didn’t realize what I said was inappropriate or hurt you in that way, and I’m sorry.”

- Be comfortable with being uncomfortable

Honour confidentiality

- As faculty and staff we need to honour confidentiality, but we cannot guarantee that another student or someone else in the space won’t share

- Encourage students to share with others only what they are comfortable in sharing and offer your space for more deeper sharing if necessary or other resources of support

Expect and accept non-closure

- Courageous conversations involve ongoing work that does not necessarily leave us feeling comfortable. Your level of discomfort will vary, especially if you have personal experiences of marginalization and have to facilitate or be a part of these conversations.

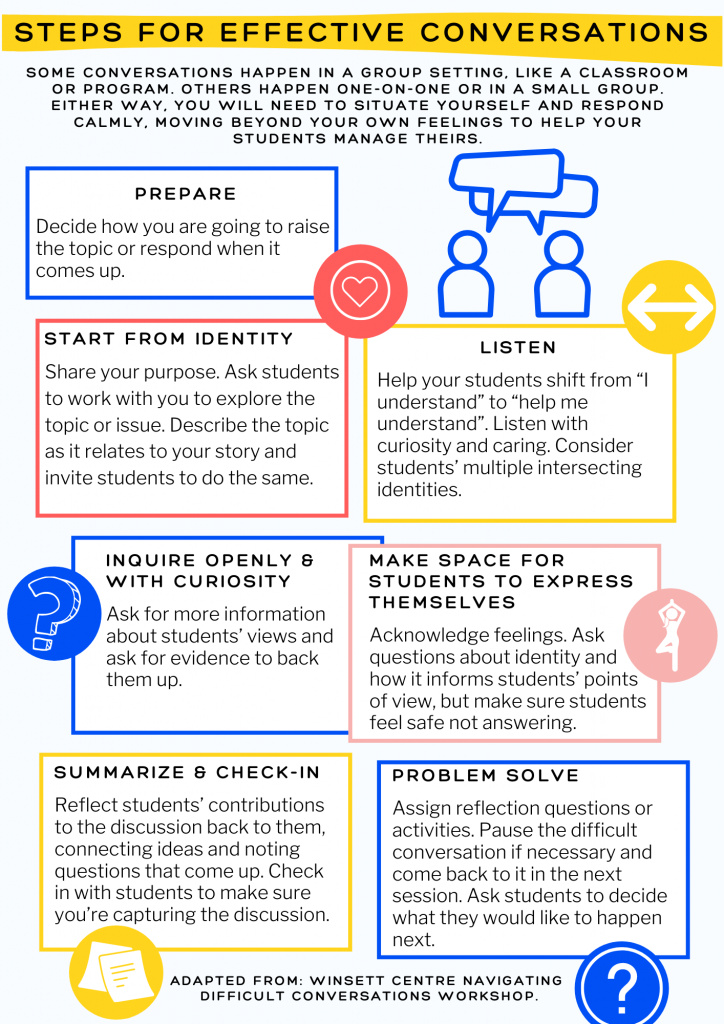

7 Steps to Effective Conversations[8]

Some conversations happen in a group setting, like a classroom or program. Others happen one-on-one or in a smaller group. Either way, you will need to situate yourself and respond calmly, moving beyond your own feelings to help your students manage theirs.

Prepare: Decide how you are going to raise the topic or respond when it comes up.

Start From Identity: Share your purpose. Ask students to work with you to explore to explore the topic or issue. Describe the topic as it relates to your story and invite students to do the same.

Listen: Help your students shift from “I understand” to “help me understand”. Listen with curiosity and caring. Consider students’ multiple intersecting identities.

Inquire Openly & With Curiosity: Ask for more information about students views and ask for evidence to back them up.

Make Space for Students to Express Themselves. Acknowledge feelings. Ask questions about identity and how it informs students’ points of view but make sure students feel safe not answering.

Summarize and Check In. Reflect students’ contributions to the discussion back to them, connecting ideas and noting questions that come up. Check in with students to make sure you’re capturing the discussion.

Problem Solve. Assign reflection questions or activities. Pause the difficult conversation if necessary and come back to it in the next session. Ask students to decide what they would like to happen next.

Why classroom conversations about diversity and identity shouldn’t be framed as difficult (opinion)

In this article Why classroom conversations about diversity and identity shouldn’t be framed as difficult (opinion), Derisa Grant argues that framing discussions as difficult further marginalizes diverse students by labeling them as promoting identity politics when, in fact, all course content reflects identity politics.[9]

|

Reflect |

- In what ways is identity present in your professional practice with students?

- What would help you feel more skilled and confident in facilitating important conversations about identity?

Hot Button Moments

What’s a hot button moment? We’ve all been there. A topic comes up and triggers strong feelings, opinions, and sometimes even conflict — and sometimes hot buttons are made worse by group dynamics. If you don’t plan for and manage hot buttons appropriately, they can get in the way of learning and create tension in your meeting, program, or class.

These critical conversations may relate to a range of topics, including race, politics, religion, gender identity, indigenization, climate change, or other subjects where you and/or students have different perspectives and opinions.

It’s critical that people who have been marginalized in the room not be looked to as experts or spokespeople for all members of their social identity group — all Indigenous people for example. People who face barriers to equity are not responsible for the labour of educating their peers. Be prepared to offer resources and supports so all students can learn about the hot topic at hand.

Inaction is still action. When you witness a biased, stereotypical, or discriminatory comment, not saying anything can cause harm. If you don’t know how to proceed in that moment, acknowledge that what was said is not okay, and that you will do some work and come back to it later.

|

Reflect |

With the right approach, hot buttons can be a great opportunity for learning and growth. Reflect on your own professional practice up till now.

- Think back to a hot button moment you’ve experienced as an instructor or student services professional. How did you handle it?

- How did the hot button moment feel while it was happening? How did you feel afterwards? How do you think others in the room felt during and afterwards?

- What was effective or ineffective about your response and why?

What makes a hot button moment?[10]

- Dominant narratives

Dominant narratives are stories told by the dominant culture to uphold and reinforce a dominant social group’s interests and ideologies.[11] For example, if a student starts talking about fisheries disputes in Nova Scotia from the dominant narrative of white fishermen, this could create a hot button moment when it comes up against the counter-narrative that asserts treaty rights and looks at how they are being violated. The danger of dominant narratives is that they are typically accepted as truth.

- Microaggressions

As we learned in Module 2: Personal Privilege and Bias, microaggressions are subtle forms of abuse that target people or groups through hostile, derogatory, or negative messages based on their group membership. Microaggressions can be based on any aspect of identity: socio-economic status, ability, sex, gender, gender expression or identity, sexual orientation, racialized identity, ethnicity, nationality, or religion. They often constitute a pattern of behaviour, and the cumulative effects of these small attacks can be devastating.

Read

Microaggressions in the Classroom, a resource from University of British Columbia’s (UBC) Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology.

- Personal comments

Personal comments are either used or could be interpreted as personal attacks. They might be directed at a particular person or group of people based on the speaker’s unfiltered emotional reaction, unconscious or overt bias, or membership in another social identity group.

- Generalizations

Generalizations are grand sweeping statements. Stereotypes are the most common hot button generalization. They are often rooted in the misconception that all members of a social identity group share common characteristics, views, or practices.

SNIPPET: Microaggressions in the Classroom

In this video, SNIPPET: Microaggressions in the Classroom (2:39) students talk about microaggressions they’ve experienced. You can watch the longer version here (18:03)

Words and Strategies for Hot Button Moments[12]

Another strategy to facilitate hot button moments is Diane J. Goodman’s “Straight A’s Model”. This model outlines an effective way of addressing those sudden hot button moments in the classroom:

Affirm: Affirm and appreciate people’s comments and questions.

- Thank you for asking that question. I’m sure others were wondering about that too.

- Interesting point. Let’s consider that.

- I appreciate that you raised that point.

- I appreciate your willingness to stay open and consider other perspectives.

- I know this isn’t easy to think or talk about. Thank you for raising that point.

Acknowledge: Acknowledge what people are saying. Make sure you understand what they’re expressing.

- I’m hearing you say that… is that correct?

- It sounds like you feel…

- So, from your perspective…

- It seems like you’re both concerned about… even though you’re approaching it differently.

- Those are both good examples of the effects of racism because…

Ask: Ask questions to better understand individuals’ behaviours and perspectives

- Can you tell me more about how you came to think that?

- What experiences led you to that belief?

- How would you make sense of…?

- What would it mean for you if this were true…?

- How were you feeling when…?

Add: Challenge misinformation, broaden people’s perspectives, address differences in power and privilege, and put issues in a larger context.

- It is interesting you think that, I was taught…

- This reminds me of a story I was told as a child…

- This research study found that…

- Let’s consider how the history of… may have contributed to what we see today.

- How might people’s social identities affect their experiences in this situation?

- What are some other explanations for this?

Jean-Blaise Samou: Putting students at the centre.

Supercharged Subjects

Strategies for dealing with supercharged subjects

Supercharged subjects are emotionally charged, polarizing, and can evoke strong reactions. The good news is that unlike many hot button moments, supercharged subjects can usually be anticipated and planned for.

A few strategies can help you and your students get ready to tackle them with respect and self-awareness. The key is to honour student input and help students take ownership of the discussion.[13]

- Build a foundation for discussing controversial topics. We’ve already talked about supporting students to respectfully participate in conversations. Before the supercharged subject arises, refresh students’ toolboxes.

- Introduce the controversial topic neutrally. Review different perspectives, knowledge bases, and major arguments. Describe common assumptions and biases behind specific arguments and unpack popular and prevailing attitudes.

- Talk about your shared roles and responsibilities. As a group, share and agree on ways you might respectfully discuss, learn, or disagree about the topic.

- Offer a range of perspectives. This is especially important if certain perspectives are missing from or not being heard in the group.

- Encourage students to contextualize. Discuss the cultural, historical, and social contexts of the supercharged subject. Give students a chance to process and reflect on why they think the way they do about it — then connect it to their personal experiences.

- Acknowledge both agreement and disagreement. Make these points explicit and pause to observe them together.

|

Reflect |

Review the suggestions in this section and consider:

- What topics do you engage with in your professional practice that might benefit from using some of these strategies?

- What other words, phrases, or strategies have you used that worked well? Why or why not?

- What have you learned from your students about dealing with hot button issues or supercharged topics?

Reflecting on Systems

Take a moment to reflect and think deeply about your institution as a system and how it relates to this module. Think about the written and unwritten rules, policies, procedures, practices, and traditions that define your institution. Reflect on and write a few lines answering these questions:

- Who is welcomed and can fully participate?

- Who may be excluded, discriminated against, or denied full participation?

- Whose norms, values, and perspectives does the institution consider to be normal or legitimate? Whose does it silence, marginalize, or delegitimize?

- Who inhabits positions of power within the institution?

- Whose experiences, norms, values, and perspectives influence an institution’s laws, policies, and systems of evaluation?

- Whose interests does the institution protect?

Systems of Inequity

Thank you for taking the time to reflect on your own institution in relation to this module. Being aware of the policies, procedures, practices, and traditions and how they intentionally or unintentionally privilege some groups over others is a critical first step to making education equitable. The next step is real action to combat the impacts of oppression.

Conclusion

Summary

The aim of this module is to help you handle and respond to challenging conversations in your educational practice — with students, colleagues, and others. The goal of a courageous conversation is to listen closely so we can understand each other’s perspectives, even if we don’t agree, and to keep the conversation going even when it gets uncomfortable.

This module introduced you to concepts and strategies for anticipating and navigating challenging conversations, including:

- hot button moments, where a courageous conversation can happen unexpectedly

- supercharged subjects, where a courageous conversation can be anticipated

- brave spaces, where we create and hold space for students to share their experiences and learn from one another, even when the going gets rough

Learning about courageous conversations is critical to skillfully and bravely handling challenging discussions and helping students feel supported, safe, included, and able to learn — something all students are entitled to.

Courageous conversations are an opportunity to challenge ourselves and grow together with our students.

Learn More

Do

The University of Michigan Center for Research on Teaching and Learning (CRTL) provides an amazing selection of resources for anticipating, facilitating, and responding to difficult discussions and moments, as well as classroom incivility:

- Guidelines for planning and facilitating discussions on controversial topics

- Strategies for making productive use of tense or difficult moments (PDF)

- Facilitating Challenging Conversations in your Classes (blog post)

- Sample guidelines for class participation

- Guidelines for responding to particular topics and tragedies

- Responding to Incivility in the College Classroom

Read

Three posts by Tereigh Ewert posted to the University of Saskatchewan’s Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching Effectiveness (GMCTL) Educatus Blog:

Part 1: Tools and Strategies for ‘Hot Topics’ posted October 11, 2016 to Educatus.

Part 2: Tools and Strategies for ‘Hot Topics’ posted October 17, 2016 to Educatus.

Part 3: Tools and Strategies for ‘Hot Topics’ posted October 24, 2016 to Educatus.

Watch

Ilana Redstone: Beyond Bigots and Snowflakes: Building Community through Viewpoint Diversity (5:47) Our worldviews shape how we filter information and how we understand and interpret the world. So, what happens when you and I see the same thing, the same action, but our filters are radically different?

Engage

Continuing Courageous Conversations Toolkit by Lisa D’Aunno and Michelle Heinz, University of Iowa School of Social Work. The Toolkit contains several group exercises designed to guide participants through a courageous conversation that can occur within a 20- to 45-minute time frame.

Attribution

The sections listed below were adapted from University of British Columbia and Queen’s University. (n.d.). Inclusive Teaching: Module 1: Power, Privilege and Bias and Module 5: Difficult Conversations. [online curriculum]. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license:

- Learning Objectives from Module 5 – 1. Introduction to Difficult Conversations – Learning Outcomes

- Unpacking Language: Key Terms paragraphs from Module 1 – 2. Unpacking Language

- Words and Strategies for Hot Button Moments text from Module 5 – 3.2 Strategies for Hot Button Moments – Part 2

- Grant, D. (2020, July 15). On difficult conversations. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/07/15/why-classroom-conversations-about-diversity-and-identity-shouldnt-be-framed ↵

- Adapted from D'Aunno, L. et al. (2017, August 8). Ground Rules for Continuing Courageous Conversations. Continuing Conversations Toolkit. http://www.polkdecat.com/Toolkit%20for%20Courageous%20Conversations.pdf ↵

- Warren, L. (2000). Managing Hot Moments in the Classroom. Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, Harvard University. https://www.elon.edu/u/academics/catl/wp-content/uploads/sites/126/2017/04/Managing-Hot-Moments-in-the-Classroom-Harvard_University.pdf ↵

- Adapted from University of British Columbia. (n.d.). 2.3 Clip: Navigating Difficult Conversations in the Classroom. In Inclusive Teaching. [online module]. https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/31444/pages/2-dot-3-clip-navigating-difficult-conversations-in-the-classroom?module_item_id=1672646 ↵

- Cook-Sather, A. (2016). Creating brave spaces within and through student-faculty pedagogical partnerships. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education. Issue 18. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/tlthe/vol1/iss18/1 ↵

- Adapted from: From safe spaces to brave spaces: A new way to frame dialogue around diversity and social justice by Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens in The Art of Effective Facilitation: Reflections from Social Justice Educators. ↵

- List adapted from D’Aunno, L. & Heinz, M. (2017). Continuing courageous conversations toolkit (p.3-4). University of Iowa, School of Social Work. http://www.polkdecat.com/Toolkit%20for%20Courageous%20Conversations.pdf ↵

- Adapted from WinSETT Centre Navigating Difficult Conversations Workshop. ↵

- Grant. D. (2020, July 15). On difficult conversations. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/07/15/why-classroom-conversations-about-diversity-and-identity-shouldnt-be-framed ↵

- Section adapted from University of British Columbia. (n.d.). Hot Button Moments. In Inclusive Teaching [online curriculum] https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/31444/pages/3-hot-button-moments ↵

- Adapted from University of Michigan Inclusive Teaching. (n.d.) Dominant Narratives. https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/inclusive-teaching/wp-content/uploads/sites/853/2021/12/Dominant-Narratives.pdf ↵

- UBC 3.2 ↵

- section adapted from UBC Module 5 unit 4 ↵