7 SCHOOLS AS A MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION SETTING

Derica Porier; Jenna Hunt; Mackenzie Wesley-James; and Nora Dunn

CHAPTER 7: SCHOOLS AS A MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION SETTING

Why are schools viewed as a desirable setting for mental health promotion? This chapter will highlight what makes schools such a unique and valuable setting for mental health promotion by examining the programs, features, and frameworks that guide current approaches and programming. Current efforts devoted by the Canadian province of Nova Scotia act as an example and case study for reviewing the resources, goals, and current implementation of effective and sustainable school mental health promotion.

7.1 KEY THEMES AND MAIN IDEAS

7.1.1 Introduction

Mental health promotion (MHP) in schools is concerned with embedding efforts to promote and sustain positive mental health within a school learning environment (Healthy Child Manitoba, n.d.). Based on definitions and aims on general mental health promotion, this involves implementing practices, policies, and programs which both enhance protective/promoting factors of positive mental health and reducing risks for poor mental health at school (Barry & Jenkins, 2007; Cavioni et al., 2020). The diverse and wide-reaching environment that schools provide introduces space for many beneficial opportunities and extended impact, but also many barriers. Thus, school mental health promotion also extends beyond promotion and prevention of mental health to build broader social and emotional competence that beneficially impacts a broader range of social, academic, and health outcomes (Barry & Jenkins, 2007; Cavioni et al., 2020). New programs and initiatives are actively created, implemented, and evaluated to advance mental health promotion in school settings around the globe. Synthesizing current theoretical and empirical evidence and frameworks, as well as, reviewing current practices will inform how to best capitalize on strengths and overcome barriers to mental health promotion at school.

7.1.2 Rationalizing school as an effective MHP setting

Accommodating the Settings-Based Approach to MHP

A setting-based approach to MHP has been discussed since the 1980’s and using schools as a MHP setting was first addressed with the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. It states that “health is created and lived by people within the settings of their everyday life” (WHO, 1986). Schools continue to be recognized as a very strong setting for MHP largely because of their ability to reach a broad population, as well as both the diversity and already-existing structural frameworks within the school setting (Gugglberger, 2021).

Schools have the potential to deliver multifaceted interventions in multiple different settings, such as classrooms, schoolyard, or individual activities. There are also existing supports (ie., school staff, parents, etc.) which can act as unique assets to school-based mental health promotion efforts for youth and can also benefit from school MHP programming (Rones & Hoagwood, 2000). Combining these supports with the existing structure within school-settings, demonstrates that schools provide both enhanced supports and existing educational structures, through which mental health promotion programs can be implemented.

Addressing youth mental health: A population in-need

Another distinct and attractive feature of school-based mental health promotion is that youth largely compose the target population (Gugglberger, 2021). The prevalence of mental disorders amongst youth is an increasing issue across the globe. The age of onset for most mental disorders is early; 50% of adults with mental health disorders experiencing them before the age of 15 (Kessler et al., 2005). In 2001, the WHO reported that schools “can and should” help prevent suicide and enable kids to develop positive mental health in their schools (Jane-Llopis & Barry, 2005). Schools are an ideal MHP setting to address these urgent gaps because youth spend the majority of their child and adolescent lives in school settings and during these periods they are in key developmental periods where promoting mental health competencies can bring both short- and long-term benefits (e.g., resilience against mental health struggles and disorders, empowerment; Gugglberger, 2021; Healthy Child Manitoba, n.d.).

Empirical support: What does the evidence say?

The school environment provides a setting where mental health promotion efforts can leverage existing structures, supports, and reach to be efficient in promoting mental health within a population in-need. Given these strengths and opportunities, MHP in schools has the potential to be a highly effective and useful MHP strategy. Existing empirical evidence supports this effectiveness, with many programs demonstrating improved mental health outcomes and competencies, as well as broader positive social, emotional, and educational outcomes (O’Reilly et al., 2018; Weare & Nind, 2011). However, program reviews, implementation frameworks, and evaluative evidence-based research are limited compared to the scope and promise of school-based MHP initiatives (Higgins and Booker, 2022; O’Reilly et al., 2018). This creates variability in program effectiveness (Weare & Nind, 2011). Current evidence suggests that the most effective mental health promotion programs in schools balance universal and targeted initiatives, include skills education, include parents/teachers/peers, prioritize positive mental health, start programs early-on in youth and continue for longer periods into later development, use multiple delivery modalities and build off existing curriculum, and employ an approach that integrates the whole-school population (Rones & Hoagwood, 2000; Weare & Nind, 2011).

7.1.3 Theoretical Background for School-Based MHP

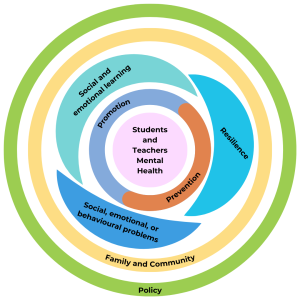

Given the overlap of schools and their relevance within sectors of community, public health, and youth and professional development, there are many disciplines which inform theory relevant to school MHP. However, since school MHP has being defined and studied multi-dimensionally, there is no one set standardized theoretical framework informing school mental health promotion (Higgins & Booker, 2022). One more recently proposed theoretical framework for school mental health encompasses aspects of both the socio-ecological theory, as well as relevant promotional and preventive mental health strategies and is depicted in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Adapted Visualization of A School Mental Health Theoretical Framework originally designed by Cavioni, Ornaghi, and Grazzani (2020).

Ecological Theories: Socio-Ecological models

The socio-ecological model is applied within health promotion generally, enforcing that efforts must be implemented across multiple socio-ecological levels. In relation to mental health and development specifically, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model offers a relevant theoretical approach because it focuses on child development and the role of prominent environments, like school (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The model situates the child within a nested group of interconnected and dynamic systems that interact to influence child development over time. Microsystems are the most proximal systems to the child and together can have direct impacts on the child’s development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Thus, within this model, school can be seen as a microsystem, that should leverage other microsystems (i.e., parents, peers, etc.) to create the best proximal environment for the child. However, it’s necessary that more distal systems (i.e., school boards, government, etc.) create the frameworks for this to be possible. Bronfenbrenner’s theory was more recently updated as a bio-ecological theory to also account for the child’s own biology, cognition, and emotions that bi-directionally interact with the surrounding systems to foster change (Bronfenbrenner, 2001). This emphasizes the need to also build and acknowledge cognition and emotion building individual factors that can improve a child’s mental functioning and well-being at school.

Educational Change Theories:

Educational change theories are action-based and focused on outlining and then acting on all the relevant factors required to define, understand, address, and evaluate a particular goal or problem within the school setting (Fullan, 2006; Hargreaves & Shirley, 2009). Although there are a wide variety of specific theories and related frameworks, two major components include the identification of multi-level health promoting factors that both include and look beyond socio-ecological context and a practical focus on how the educational system can leverage these. These theories support also defining non-contextual factors that programs should focus on to enhance mental health. Teaching developmentally relevant social-emotional competencies (e.g., self-awareness, relational skills), resilience, and preventing problematic social, emotional, and behavioural difficulties have been identified as effective means to promoting positive outcomes, mental health, and well-being in schools (Cavioni et al., 2020; Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, n.d.). Additionally, change theories emphasize the importance of outlining and adhering to clear steps to ensure success, sustainability, and continuous improvement (Hargreaves & Shirley, 2009). This emphasizes the importance of studying and practicing effective implementation and evaluation strategies and monitoring for school based MHP programs, particularly those which work effectively within existing educational structures and frameworks (Rowling, 2009).

7.1.4 Approaches and Frameworks Specific to School MHP

The Whole School Approach

The whole school approach integrates the theoretical influences above, particularly socio-ecological, into a general approach specific to school MHP. The approach supports holistic school MHP, reflecting the shift in viewing mental health more holistically, rather than as only focused on mental illness (Anwar-McHenry et al., 2016). A whole-school approach aims to foster positive mental health at school through multi-pronged efforts (i.e., staff/parent engagement, curriculum design, behaviour policy, etc.) by working collaboratively with all parts of the school community and considering the effects of local and government policies (O’Reilly et al., 2018). The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated empirically and has resulted in widespread use and application of this approach within school based MHP research and practice (Anwar-McHenry et al., 2016; O’Reilly et al., 2018; Weare & Nind, 2011, Wyn et al., 2001). Positive findings emerging from frameworks and interventions adopting the whole-school approach support the idea that MHP needs to be considered in all aspects of the school environment by using strategic, holistic, community-involved perspectives to produce optimal outcomes (Anwar-McHenry et al., 2016; O’Reilly et al., 2018).

Existing Frameworks: Applying Approaches and Theory

There are a wide range of frameworks that have guided school based MHP programming within various schools or regions with specific aims and needs. Although they often incorporate similar broad theoretical influences and approaches, frameworks often slightly differ depending on their scope and field of origin.

The WHO, in collaboration with the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) put forth a broader Health Promoting Schools (HPS) framework which subscribes to the whole-school approach (WHO & UNESCO, 2021). The HPS framework includes eight global standards required for health promoting schools: government policies and resources, school policies and resources, school governance and leadership, school and community partnerships, school curriculum, school social-emotional environment, school health services, and school physical environment (see Figure 14; WHO & UNESCO, 2021).

Figure 14. Overview of the Global Standards and Statements for Health Promoting Schools (WHO & UNESCO, 2021)

Note. From a report by WHO and UNESCO (2021), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/)

Many other frameworks have been developed across various regions and countries which differ in their depth and scope; however, most adopt the whole-school approach (O’Reilly et al., 2018). For example, the Comprehensive School Health framework is a Canadian-based framework aiming to improve education outcomes for students while also addressing school health in a holistic way (JCSH, n.d.). It includes four components: social and physical environment, teaching and learning, health school policy and partnerships and services (Government of Manitoba, n.d.). Some frameworks also take influence from an educational change-based approach, outlining the required steps, levels, and domains required to achieve improved functioning and well-being among students.

7.1.5 School MHP in Practice: Programming and Interventions

School-based MHP programs and interventions are often designed to build desired competencies and reflect appropriate approaches in ways that best reflect the needs, constraints, and goals of the involved students, schools, educational system, and government. Implementation of broad approaches and frameworks within these programs often involves focusing on some of the many competencies and practices that are theoretically relevant and empirically supported within the health promotion and/or education fields. This could include resilience, partnerships, participation, empowerment, holism, equity, and sustainability (Gugglberger, 2021; O’Reilly et al., 2018). Further, approaches can be targeted (i.e., towards high-risk students or certain health outcomes) or universal, and can also vary in how they are structured (i.e., classroom-based skills training; changing the school environment; Barry and Jenkins, 2007). Although more holistic and multi-modal approaches are favoured in research, there is also a need to incorporate targeted interventions to supplement and balance universal/broader approaches (O’Reilly et al., 2018). The Gatehouse Project, for example, is an intervention designed for a systematic and sustainable MHP in secondary schools, aiming to prevent depressive symptoms by promoting a more positive school social environment and address common emotional needs of youth (Patton et al., 2000). The project was informed by epidemiology of adolescent mental health issues, attachment theory, education reform research, and health promotion theory and practice. Impacts included positive change in schools’ social and learning environments, fostered important skill development through the school curriculums, and strengthened the relationships between the school and community (Patton et al., 2000). Furthermore, an article written by Domintrovich & Greenberg reviewed the Childhood Development Project (CDP), a prevention program focused on creating school environments that are “caring communities of learners” (2000). The CDP provided school-wide community-building activities that promoted school bonding, reinforcing partnerships, cooperative learning, discipline, and self-control. For four years implementation data was collected and evaluated, and the program yielded positive results in relatively small schools (Domintrovich & Greenberg, 2000). Thus, existing interventions support the crucial role schools play in mental health, development, and education in a variety of diverse ways.

This introduction section has reviewed the current conceptualization, empirical support, influencing theory, and practice and scope of school-based mental health promotion. The remainder of this section describes school based MHP in Nova Scotia to exemplify the approaches and application of school MHP in a specific region.

7.1.6 Case Study: Examining School Mental Health Promotion in Nova Scotia

Theoretical Influences: The Whole School Approach

Initiatives towards MHP in the school setting have the potential to create and foster positive impacts on the mental health of youth populations. Several different policies and programs within the province of Nova Scotia are being developed to promote and support the mental health and well-being of these young individuals in the school environment. Some of the programs being developed locally over the last couple of decades may be recognized such as initiatives including Health Promoting Schools (HPS), Comprehensive School Health, as well as Healthy School Communities (Nova Scotia Health Authority [NSHA] et al., 2015). These developing programs and initiatives typically take on a whole-school approach, which involves acknowledging all aspects of the school environment and their potential in promoting mental health.

The rationale and practical guidelines relevant among Nova Scotia health and education agencies and groups for their whole-school approach is outlined in a practical guiding document (Nova Scotia Health Authority [NSHA] et al., 2015). They emphasize the bi-directional relationship between an enriched school environment and positive health/wellbeing outcomes, as students who thrive in the learning environment are often healthier, and students who are healthy tend to learn better (Nova Scotia Health Authority [NSHA] et al., 2015). MHP in the classroom often encourages and supports better academic achievement and attendance as well as better classroom behavior which is likely to increase the social and emotional well-being of students (Nova Scotia Health Authority [NSHA] et al., 2015). Paired with MHP in the social and physical environments of schools and a policy shift including MHP efforts, there is great potential for students to develop skills and thrive. In such an environment, students as well as others have the potential to live a long, healthy life both physically and emotionally (Nova Scotia Health Authority [NSHA] et al., 2015).

The Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Development’s Continuous School Improvement Framework and SchoolsPlus uphold the same philosophy which supports the whole-school approach associated with MHP in the school environment. In 2005, Health Promoting Schools (HPS) was introduced in Nova Scotia and has now become a partnership between several organizations including the Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness (DHW), the Nova Scotia Health Authority (NSHA) as well as the public-school boards in the province (Nova Scotia Health Authority [NSHA] et al., 2015). Additionally, The Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness allocates and provides funding for eight public school boards within the province, as well as the Mi’kmaq Kina’matnewey, who work closely with the Nova Scotia Health Authority and other organizations to strengthen school communities across the province and improve the quality of academic and health outcomes in students (Nova Scotia Health Authority [NSHA] et al., 2015). These partnerships between both health and education organizations and the frameworks which arise from them contribute to enforcing the whole-school approach and provide the opportunity for coordinated efforts ensuring that NS schools and students can reach their full potential.

Frameworks: The 4 Pillars of Comprehensive School Health

The four pillars (social and physical environment, teaching and learning, partnerships and services, as well as healthy school policy) from the Joint Consortium for School Health (JCSH) have been adopted by Health Promoting Schools (HPS) in Nova Scotia (Nova Scotia Health Authority [NSHA] et al., 2015). The four pillars create the foundation for comprehensive school environments which prioritize both health and education and play an extremely important role in developing and implementing a whole-school approach to MHP (JCSH, n.d).

In Nova Scotia, the teaching and learning pillar is partly expressed through a healthy living curriculum which focuses on certain health issues which are found to be significant in youth populations. These include mental and emotional health, physical activity, healthy eating, substance use and gambling, injury and communicable disease prevention, as well as sexual health (Nova Scotia Health Authority [NSHA] et al., 2015).

Within the social and physical environment pillar, the social environment involves the quality of relationships between the students and staff and the emotional well-being of students (JCSH, n.d). The social environment is heavily influenced by the relationships between the school and the community/families (JCSH, n.d). This type of environment should also support and encourage healthy decision making within the school environment, drawing on concepts such as autonomy and connectedness (JCSH, n.d.). The physical environment is concerned with the physical structures and surroundings such as the buildings, equipment, and play space within the school environment (JCSH, n.d). This also includes things such as sanitation and healthy foods available to the students and staff within their environment. The physical environment should also be designed to promote and support safety and accessibility for all those within the school environment (JCSH, n.d.).

The healthy school policy pillar can be encompassed by the policies, guidelines, and practices which are in place to promote and support the well-being and achievement of the students and other school community (JCSH, n.d.). This pillar is also essential in building the guidelines that enforce respectful, safe, inclusive, and caring environments within schools and the school system for all students, staff, and community members within the school environment (JCSH, n.d.).

Within the final partnerships and services pillar of comprehensive school health, partnerships are defined as the connections and relationships between the school and its students’ families (JCSH, n.d.). Partnerships are often developed among schools, community organizations, and working government sectors making them essential in advancing school health province wide. Many advancements and improvements are facilitated and/or strengthened through collaboration and innovation across education and health sectors. Services can be defined as acts of assistance which promote and support well-being and health within the community and school environment. These are often community or school-based and can be extremely important and beneficial for those involved, particularly when enhanced by various partnerships (JCSH, n.d.).

Programs and Initiatives: SchoolsPlus and Uplift

SchoolsPlus is a collaborative school mental health approach provided by the Nova Scotia Health Authority (NSHA) through the Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (NSDEECD) which is available across the province to children and youth populations (NSDEECD, 2023a; NSHA, n.d.). This program addresses a wide range of important subjects including but not limited to alcohol/drug use, anxiety, grief, stress, eating disorders, etc. SchoolsPlus utilizes a whole school approach which includes and supports the unique needs of the children as well as their families within the school environment and the community (NSHA, n.d.). School sites participating in the program receive an outreach worker and facilitator who connect students, families, communities, and staff members with the resources and services needed within the school environment (NSDEECD, 2023a). SchoolsPlus also provides school mental health clinicians at school sites to help treat mental health issues and provide support to students in-need (NSDEECD, 2023a). The programs and services that schools relate to through SchoolsPlus include outreach/mentoring programs, homework clubs, employment support, health services, breakfast programs, community gardens, early years centres, community policing, youth groups, parenting support, as well as recreational programming (NSDEECD, 2023a). Although there are no formal studies or research papers examining the effectiveness of SchoolsPlus, the NSDEEC produces and releases quarterly newsletters which highlight the important SchoolsPlus initiatives and projects running across Nova Scotia (NSDEECD, 2023c). Stakeholders work to continue SchoolsPlus as part of Nova Scotia’s Action Plan for Education. Additionally, efforts are expanding to reach more NS families and youths using SchoolsPlus to help support their engagement and success (NSDEECD, 2023a).

UpLift is another MHP initiative in Nova Scotia based out of the Healthy Populations Institute at Dalhousie University (UpLift, 2018a). Uplift promotes and supports both health and learning for youth across the province by utilizing a Health Promoting Schools (HPS) approach through partnerships with schools, universities, communities (UpLift, 2018a). One of the most important components of the approach used by UpLift is that it provides an opportunity for youth to engage and drive the changes within their environment that they want to see. This is possible with the collaboration between HPS Leads and Youth Engagement Coordinators within the school communities across Nova Scotia (UpLift, 2018a).

UpLift operates on five key strategies to ensure that all children can learn and grow in a healthy, educational environment. The five key strategies include youth, school, and community engagement; planning and evaluation; partnership and leadership; capacity building; and knowledge exchange (UpLift, 2018b). Youth, school, and community engagement involves including youth in the decision making when it comes to change for their schools, families, and communities. Policies and programs become more effective and impactful when youth can actively participate in their development and implementation (UpLift, 2018b). Planning and evaluation is done periodically through data collection and analysis as well as process evaluation to ensure that programs and policies are current and up to date. This process involves students, school staff members, Youth Engagement Coordinators, as well as other stakeholders within the Health Promoting Schools network in Nova Scotia (UpLift, 2018b). This process highlights how partnership and leadership are key aspects of the UpLift organization. Collaborating with different sectors such as health and education and with students themselves fosters healthy learning environments for children to reach their full potential (UpLift, 2018b). Youth/school community involvement emphasizes capacity building which allows these individuals to grow their skills and knowledge and make impactful change. UpLift also prioritizes knowledge exchange by developing tools and resources to educate individuals on the benefits of Health Promoting Schools for youth populations (UpLift, 2018b). Additionally, many of these resources are accessible in French and English, including, manuscripts, evidence-based research, surveys, impact and evaluation reports, project frameworks, infographics, as well as case studies (UpLift, 2018c).

Current Steps Forward

Nova Scotia is actively working and investing to provide more mental health and wellness resources for schools. For example, mental health and wellness grants and online resources are also being developed and allocated towards providing additional resources and services in schools for students, families, and communities (NSDEECD, 2023b). Some of these resources include an annual investment of $2 million towards the Healthy Schools Fund, 70 new school counsellor positions and 19 psychologist positions, more than 1000 new positions in the education sector to help support students and teachers, online classroom resources for teachers about mental health, as well as a virtual platform available to students and families to access services (NSDEECD, 2023b). These efforts demonstrate that the province of Nova Scotia is continuously taking steps to help improve and implement MHP in the school setting through numerous initiatives and programs designed to benefit students, families, and their communities.

In this case study, we have learned about the 4 components for improving education outcomes according to the comprehensive school health framework (environment, teaching and learning, policy, and partnerships). We examined how Nova Scotia implements the JCSH framework through initiatives and school mental health programs such as SchoolsPlus and Uplift.

7.2 GAPS AND LIMITATIONS

Limitations in school mental health promotion include: barriers in defining and understanding (school) mental health, lacking integration and synthesis of theory and empirical evidence in current practice, and minimal focus on understudied and underserved sub-populations in schools.

7.2.1 Introduction

School is a setting that is imperative in the development of all school-age children and adolescents. The essentiality of school expands far beyond the academics, as it is a critical setting for many key areas of development, including mental health. These areas of development also include the development of social and emotional skills, along with a basic understanding of self-concept (National Research Council (US) Panel to Review the Status of Basic Research on School-Age Children, 1984). When focusing on the aspect of mental health within schools, there is significant evidence on how schools aid in not only the identification of mental illness, but also support of mental illness, and MHP. These facets are beneficial throughout the student population, and extend to staff, parents & guardians, and members of the surrounding community (Gugglberger, 2021). Regardless of the concrete evidence supporting the connection between the setting of school and MHP, there are still several gaps and limitations missing from the existing research.

7.2.2 Problems with Definitions and Understanding of Mental Health

Despite existing research expanding on the measures of MHP that are implemented in schools, there is inconsistency within the true definition of mental health and school mental health. Many school MHP studies reference the holistic MH definitions (i.e., World Health Organization or Public Health Agency of Canada) honouring that mental health encompasses both positive mental health and mental illness (e.g., Weist & Murray, 2008). However, other studies and programs often treat or educate on mental health as solely the absence of mental illness, with limited or no incorporation of positive mental health and well-being (e.g., Campos et al., 2018). This is undesirable given that school MHP interventions emphasizing positive mental health have been shown to be particularly effective (Weare & Nind, 2011). This limited view of mental health can also translate into decreased understanding of holistic mental health among those in the school environment, which can harm the implementation and effectiveness of school MHP programming. For example, school MHP involving teachers often fails to be incorporated into pre- or in-service teacher education and causes a lack of competence to follow policy directions for MHP programs (Askell-Williams & Cefai, 2014). While teachers generally held a positive attitude towards promoting mental health, half revealed that their mental health knowledge was limited and they lacked the proper resources to promote student’s mental health (Askell-Williams & Cefai, 2014). Given the important of teacher engagement in school MHP research and practice, comprehensive mental health training for educators and curriculum-based mental health education for students might enhance their MH literacy and their ability to engage with and benefit from MHP interventions at school (Gugglberger, 2021; OReilly et al., 2017). It’s imperative that school-based programming incorporates the holistic mental health definition and provides the comprehension and training required for confident and informed participation in school MHP interventions. Ensuring that those involved in programs (from researchers to participants) share and adopt a consistent understanding of holistic mental health and school based MHP will remove comprehension barriers and enhance both research and practice.

7.2.3 Research Gaps: Missing Evidence and Synthesized Theory

Various research reviews have identified a wide range positive outcomes emerging from school based MHP programming (O’Reilly et al., 2018). However, there remains a need for a stronger empirical evidence base, as well as synthesized and consistent theoretical frameworks and terminology (Cavioni et al., 2020; O’Reilly et al., 2018). Much of the current school MHP practice is situated within the health promotion context, which is useful, but not always tailored to leverage the unique school environment and educational environment (Rowling, 2009). Additionally, there is a need to synthesize theory and evidence contributions across education and health promotion to adopt consistent frameworks that have a clear theoretical and conceptual grounding. Existing empirical findings suggest that intervention effectiveness varies between studies and remains contingent on many factors (i.e., program fidelity, multi-modal delivery, etc.) that are not consistently prioritized across existing interventions (O’Reilly et al., 2018; Weare & Nind, 2011). Additionally, many studies lack long-term evaluation of intervention outcomes (O’Reilly et al., 2018). This limits comprehensive understanding of interventions long-term effectiveness and reduces the strength of available evidence to warrant continued support of these interventions by funding institutions.

7.2.4 Lack of Accommodation for Distinct Populations

Despite the high level of diversity in school settings, there is a gap involving the lack of understanding on how specific school populations and sub-populations respond to MHP in schools. Many studies focus on single age-groups, for example, Jerusalem & Hessling (2009) findings involve students ranging from the young child to adolescent-age, while Timimi & Timimi (2022) focus on secondary school students. The roles and perspectives of teachers and other school staff are often overlooked despite the importance of their engagement and training to intervention success (Gugglberger, 2021). Additionally, cross-cultural research on school MHP, particularly in lower-income countries, is limited (Gugglberger, 202). Identifying and studying unique populations and particular demographics over time, might highlight and distinguish important demographic differences/needs and developmental changes that would impact the effectiveness and guide the implementation of relevant interventions.

Evidence supports a mix of both universal and targeted approaches to school MHP (O’Reilly et al., 2018; Weare & Nind, 2011; Wyn et al., 2001). This is important considering the many factors that might place certain people at higher risk for developing mental health problems and many barriers that some people might disproportionately face when attempting to promote their mental health. Evidence suggests that individuals from marginalized communities will suffer with mental health more than individuals from majority communities (Rasmussen et al., 2016). Supportive schools could support these individuals, as well as improve health in deprived areas. Further research directed towards varying school populations can aid in the identification and procedure for addressing unique challenges, as well as the development of both targeted and universal MHP strategies that effectively cater to populations in need.

We have learned that to improve school mental health promotion, we must enforce a universal definition of mental health, which includes positive mental health, address gaps in research and practice, complete more research and offer accessible programming under-studied and underserved populations.

7.3 FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Advancing research in school mental health programs plays a crucial role in improving the practices which will helping children develop positively into healthy teenagers and adults (Healthy Child Manitoba, n-d). In this section we will explore how school mental health promotion research and practice can address the many existing limitations by solidifying and integrating the empirical and theoretical knowledge bases and theory. Special topics and considerations are also discussed.

7.3.1 Improving the Foundations

Integrating Theory and Empirical Evidence

To facilitate synthesis of theory and its effective implementation in practice, there is a need to better accommodate and consider educational factors (i.e., school conditions, structures, etc.; Rowling, 2009), not just health promotion theory. Incorporating key aspects of educational change, such as, leadership, capacity building, and professional learning, will ensure comprehensive frameworks and interventions that are best suited to MHP in a school environment (Higgins & Booker, 2022; Rowling, 2009). Additionally, further concept analyses and theoretical reviews may be useful in integrating theory, conceptual understanding, and inconsistent terminology across both health promotion and educational literature. It’s essential that this synthesis is reflected in practice as well, by creating integrated frameworks and interventions. For example, the MindMatters program was derived from synthesized education and mental health promotion frameworks (i.e., whole school approach) and strategies and involved collaboration with professionals from both sectors to plan the program design and implementation at a national level (Wyn et al., 2001). Adopting a similar whole-schools-based framework has also demonstrated success in implementing mental health promotion campaign that was then able to successfully facilitate school cohesion, a sense of belonging for students, improved behaviour, and academic success, and reduced stigma around mental illness (Anwar-McHenry et al., 2016). Therefore, more programs adopting similar innovative and integrated frameworks and strategies have the potential to be highly successful and should be evaluated empirically to identify best practices and overcome barriers (i.e., time and costs of a truly integrating whole-school approach).

Solidifying a Quality Evidence-Base

O’Reilly et al. (2018) state, “there is still a need for a stronger and broader evidence base in the field of MHP, which should focus on both universal work and targeted approaches to fully address mental health in our young populations.” (p. 660). O’Reilly et al. (2018) recommends that future research be guided by evidence of effectiveness from previous programs to create more sustainably designed future programs. This can be achieved by ensuring a detailed plan, including clear goals, guidelines, and expected outcomes of the program, based on health promotion and educational change theory (Weare and Nind, 2011; Higgins and Booker, 2020). There also need for evaluation studies to clarify whether resources are being used efficiently. If a program is ineffective, it is unnecessary to spend costly time and resources on its implementation (O’Reilly et al., 2018). More longitudinal research examining program effects, outcomes, and feasibility is crucial, especially in under-studied places that might particularly benefit from school-based programming (Gugglberger, 2021). The longer time frame will permit strengthened empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of school based MHP and delineate the evolving influence of facilitators and barriers relevant in guiding future research and practice. Additionally, programs must more widely and consistently implement the factors of effective programs including better support and training for teacher/school staff involvement, focus on positive mental health, multi-modal delivery, skills training aspects (O’Reilly et al., 2018; Rones & Hoagwood, 2000; Weare & Nind, 2011). Balancing targeted and universal approaches has also been identified as beneficial (Weare & Nind, 2011). Thus, examining and implementing supportive school programming in under-represented places (i.e., lower-income countries, under-resources areas) and evaluating intervention impacts on high-risk groups (i.e., marginalized students, cultural/religious/sexual minorities) will allow study of how to address gaps in universal school interventions using more targeted MHP efforts both at school and beyond.

7.3.2 Special Topics: School Mental Health and COVID-19, Social Media, and Climate Change

More research must target new topics becoming increasingly important in children’s lives, including the COVID-19 pandemic, social media, and climate change. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed schools’ responsibilities concerning health (Gugglberger, 2021). Research shows that the pandemic has negatively affected children’s mental health (Hamoda et al., 2021); therefore, future efforts must determine how children’s mental health needs have changed since they have returned to in-person school and how new programs can meet them (Gugglberger, 2021). Similarly, as climate issues become an increasingly pressing global issue, schools have been taking more action against climate change, warranting more research investigating related mental health impacts at school and identifying the supports that a school setting might provide (Gugglberger, 2021).

With the increase in child technology and social media use, O’Reilly et al. (2018) suggest exploring digital avenues of school MHP, as its use had been limited within existing interventions. Future research is needed to determine potential benefits and costs and whether online options have sustainable intervention potential (O’Reilly et al., 2018). Since digital media can contain false information, programs need to teach children to fact-check what they read online, so that unreliable information does not negatively affect their mental health or the accuracy of their mental health literacy (Gugglberger, 2021).

7.3.3 Conclusion

When MHP is at the forefront of education, it is easy to create a learning environment that fosters and promotes positive mental health for all. The challenge is integrating MHP within the educational context. An increasing number of students worldwide are suffering from mental health difficulties, resulting in mental health becoming a leading cause of child and adolescent disability (Cavioni et al., 2020). Centralizing school as a setting focused on fostering MHP and its associated principles may help to combat the high rates of mental health among youth and well as build competencies that allow youth to thrive and grow into adulthood. The school setting provides the unique opportunity and responsibility to be able to impact, support, and connect with such a high number of children and adolescents. This importance of this responsibility is evident to Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, with an increasing number of unique and accessible school based MHP initiatives such as Health Promoting Schools, SchoolsPlus, and UpLift (NSHA, n.d.). Evidently, it is imperative that educators and school staff acknowledge their responsibility to adequately support the mental health of future generations by executing and coordinating interventions with fidelity. However, this is impossible without higher-level support and cooperation between public health promotion and education sectors (O’Reilly et al., 2017; Rowling, 2009). On a larger scale, it is important to continue building and synthesizing evidence on school-based mental health promotion, leveraging and integrating knowledge and collaboration across both health and education sectors to strength MHP in schools and inform future programming and policy needs.

In this section we have studied how school mental health promotion needs to be continually updated as our world continually changes. Programs need to involve both teachers and students, and create organized goals, plans, guidelines and expected outcomes.

Media Attributions

- AdaptedCavioniFigure © Valeria Cavioni , Ilaria Grazzani, and Veronica Ornaghi adapted by Alanna Kaser is licensed under a Public Domain license

- global-standards-on-health-promoting-schools © World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license