2 THE DETERMINANTS OF POSITIVE MENTAL HEALTH

Claire Miner; Sophia McGean; and Megan Sponagle

Have you ever wondered what components of your everyday life may contribute to your mental health? In this chapter we will learn about these factors- the social and structural determinants of mental health, how they can vary from person to person, and the levels of mental health treatment an individual may access.

2.1 KEY THEMES AND MAIN IDEAS

2.1.1 Introduction

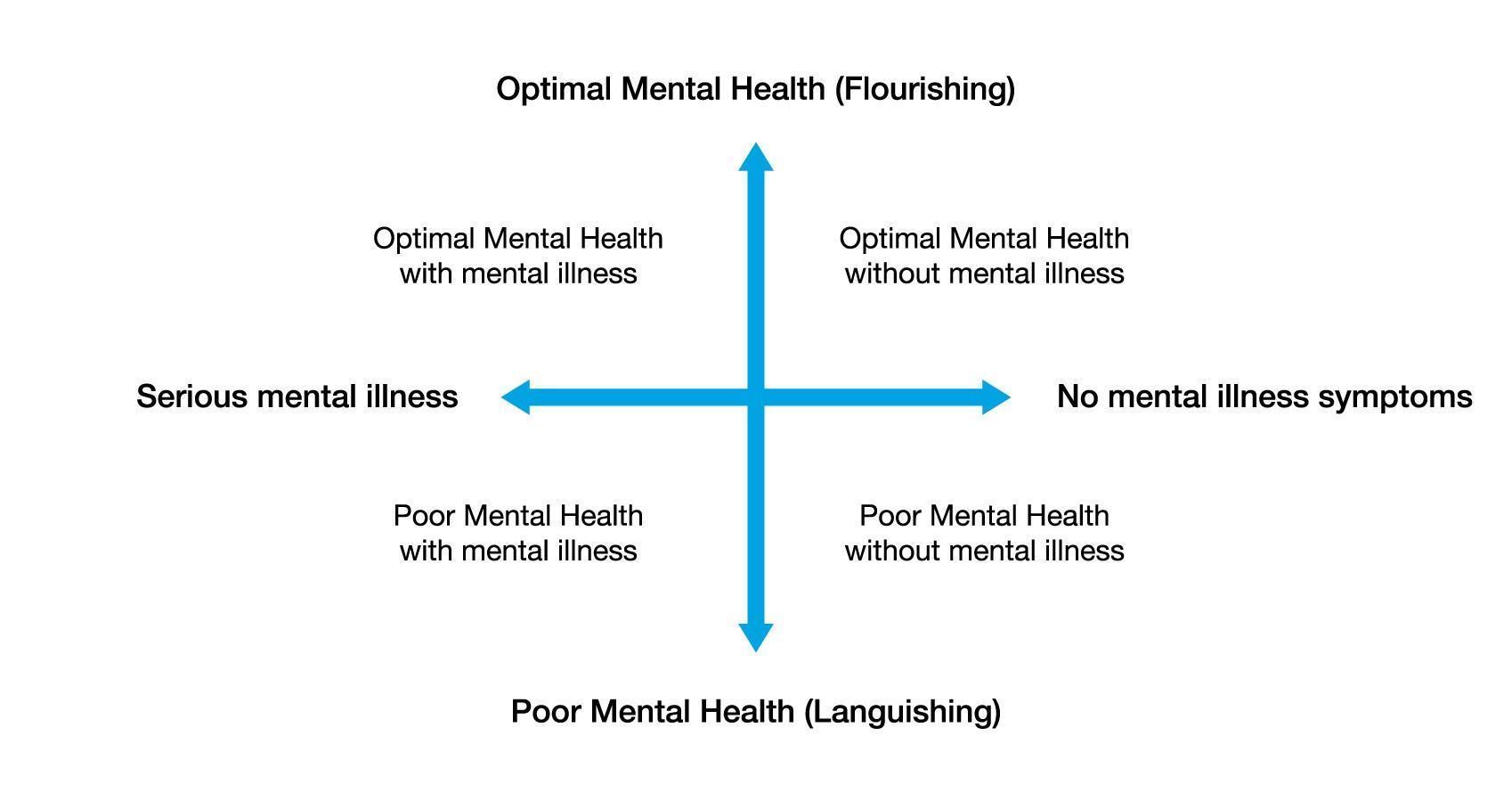

For a long time, mental health was thought of as a lack of mental illness. More recently, researchers have theorized, tested, and confirmed the idea that mental health is more than the absence of mental illness (Keyes, 2002). In fact, research showed people’s classification as languishing or flourishing were associated, but distinct from whether they struggled with mental illness or not (Barry, 2009). This means that individuals can be in a poor state of mental health (i.e., languishing), without also experiencing mental illness (Barry, 2009, pg. 6; Keyes, 2002). These empirical findings cemented the notion that mental health is more than the absence of mental health and inspired Keyes to reconceptualize mental health in a dual continua model. His conceptualization outlines mental health as a continuum from languishing to flourishing, which is overlapping, but distinct from having/not having mental illness (see Figure X). As we learned in Chapter 1, positive mental health is both an antecedent and outcome of mental health promotion (Tamminen et al., 2016). Viewing it as an outcome rationalizes MHP approaches which focus on positive mental health, while its ability to precede and enhance mental health promotion efforts, clarifies its importance as a key determinant of MHP.

2.1.2 The Social Determinants of Positive Mental Health

A determinant refers to a factor that influences the nature of something to produce a particular outcome (Merriam-Webster, 2019). Social and structural determinants of health are factors outside of the body that influences a person’s health (World Health Organization, 2023). Identifying the social and structural determinants of mental health enables us to understand why someone experiences poor mental health. Poor social determinants of health have been seen to impact one’s mental health severely. The most common mental health issues caused by social determinants of health are depression, stress, and anxiety (Barry, 2009). Alegría et al. (2018) says: “a two-way relationship exists between mental health disorders and social determinants, as poor mental health can aggravate personal choices and affect living conditions that limit opportunities” (p. 5). Future, they state, “upstream social determinants (e.g. economic opportunities) act as “fundamental causes” and typically impact health through downstream social determinants (e.g. living conditions)” (Alegría et al., 2018, p. 2).

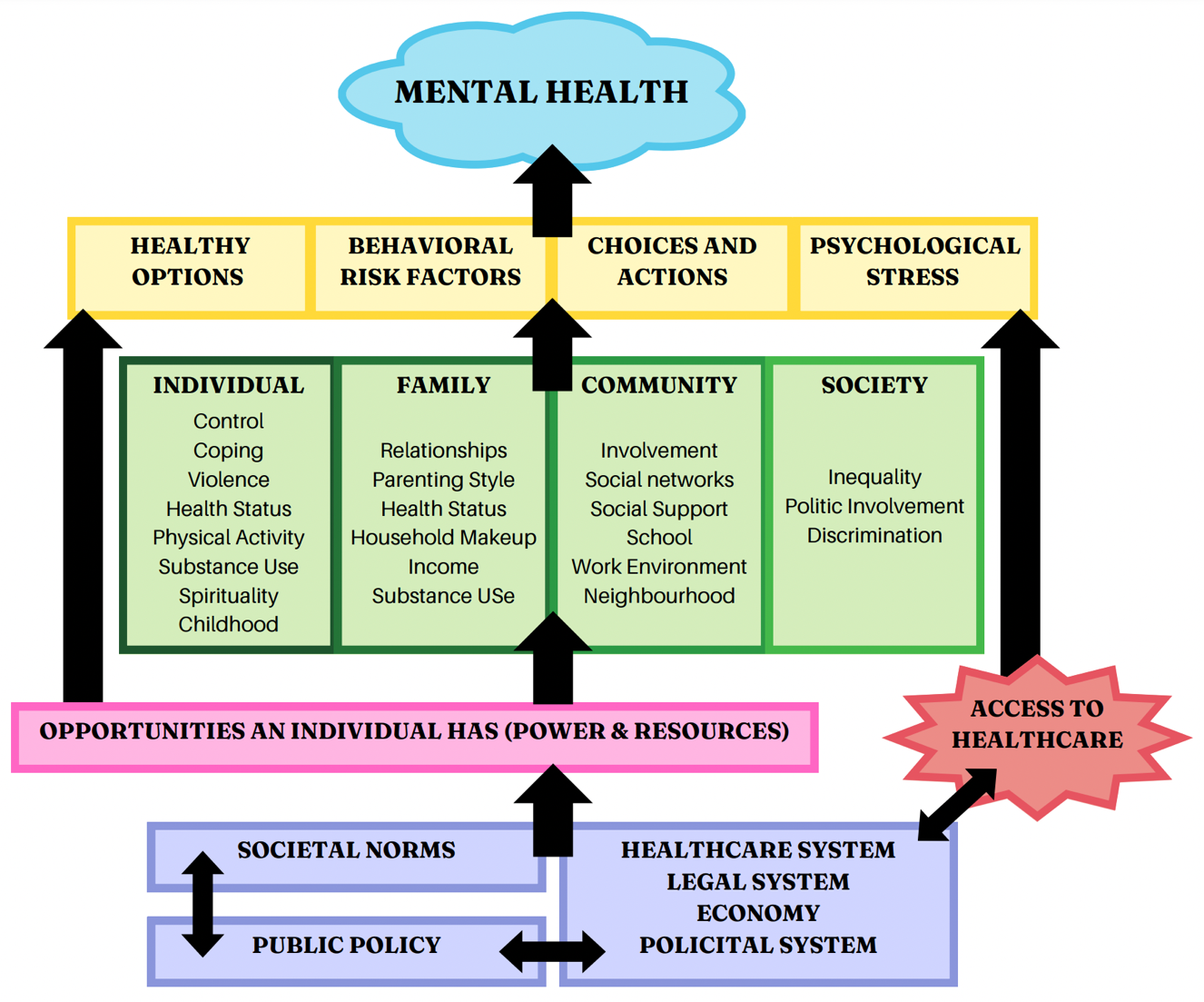

Ten years ago, Canada came across the problem of not having a surveillance system for positive mental health (Orpana et al., 2016). This led to the creation of a new list of 25 determinants specific to positive mental health, shown in Figure 7. This model follows a Socio-Ecological approach built across four levels: the individual, the family, the community, and the society (Orpana et al., 2016). The Orpana, 2016 conceptual framework for monitoring positive mental health of Canadians, found that to support areas that are currently flourishing and build up areas that are not, current frameworks, policies and programs related to mental health must be constantly updated to align with changes that occur in society and consider emerging determinants of mental health (Orpana et al., 2016).

Compton and Shim (2015) focus on less, but more specific categories, arguing that the determinants of mental health are equivalent to the social determinants of health. The five key determinants they suggest are: healthcare access and quality, education access and quality, economic stability, neighborhood or built environment, and social and community context (Compton & Shim, 2015).

Figure 7. The 25 determinants and 5 outcomes of positive mental health sorted across 4 domains (Orpana et al., 2016). This list was created by the Public Health Agency of Canada (Orpana et al., 2016).

Here we will discuss some of the determinants of mental health in more detail.

Healthcare access and quality refers to how two people with the same problem can receive very different levels of care based on outside factors (Compton & Shim, 2015). The National Collaborating Centre For Mental Health (UK) (2011) says poor access to mental healthcare can stem from care being unavailable (e.g. lack of transportation or babysitting), from not wanting to seek it out because of poor previous experiences (e.g. values and behaviours expressed by the care provider or stigma) or from being uneducated on treatment options. Alegría et al. (2018) reported that individuals who live in cities have lower rates of mental health conditions. For example, a person living in a big city that is close to a large hospital will likely receive better care than someone who lives in a very rural area and must travel a long time to get to a small medical center. Groups with poorer access to mental health care include people of colour, ethnic minorities, and older adults (National Collaborating Centre For Mental Health (UK), (2011). Many individuals with poor mental health (with or without a mental illness) are still struggling and need help, but there are not enough psychologists and psychiatrists to support this need (Purtle et al., 2020). The impact of untreated mental illness is immense, including “unnecessary disability, unemployment, substance abuse, homelessness, inappropriate incarceration, and suicide and poor quality of life” (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2020). Here in lies the importance of promoting population mental health before it becomes poor.

Education access and quality is referring to the fact that not everyone has the same access to a good education and opportunities because of that (Compton & Shim, 2015). An example of this is two people with the same level of intelligence and work ethic may not get the same opportunities because one went to a highly funded private school, and one went to a public school in a poorer community. Dreger et al. (2014) found that poor mental health was linked to less education. Educational systems with an unclear curriculum and rules were considered risks for poor mental health; whereas low tuition, assistance, and appropriate expectations were considered determinants for positive mental health (Willenberg, 2020). Teens interviewed by Willenberg (2020) “believed that teachers who were “too firm”, “stern”, “strict”, “cruel”, “unfair” or “demanding” adversely impacted their mental health” (p. 5).

Economic Stability is one of the most important social determinants of health because it is interconnected with all aspects of health. In our world money is directly linked to opportunities such as healthy food, safe housing, paying for medication, relaxation, and schooling so it makes sense that the more money a person has the better their quality of health will be (Compton & Shim, 2015). Surveys by Dreger et al. (2014) demonstrated that low economic status, structural and safety issues of the home, air and water quality, and material deprivation were associated with negative mental health, with the latter having the highest link. Higher risk of mental illness occurred in jobs with emotional strains, power gaps, coworker conflicts and in health organizations that were for profit (Alegría et al., 2018). Alegría et al. (2018) also found higher stress levels in individuals who were unemployed, had inconsistent employment or who had poor working conditions. These results held consistent even in countries with universal healthcare, showing the cause of poor mental health must be more than just being unable to afford healthcare services (Alegría et al., 2018).

Neighborhood and built environment refer to the physical environment where people live and work (Compton & Shim, 2015). Willenberg (2020) found environmental “risk factors included conflict (examples included war, brawling, flighting, coercion and massacre), lack of tolerance of religion, unemployment, corruption, badly regulated governments, poor relationships with neighbours, and failure to adapt to social change” (p. 5). This is supported by research in China, where there is a negative association between safe and satisfying neighbourhoods, and a diagnosis of depression (Alegría et al., 2018). One teen said, “the water is so dirty, it makes people stressed” (Willenberg, 2020, p. 5)

Finally, social and community context refers to belonging and feeling welcomed among other people. This is very important because it creates a sense of well-being and safety in numbers (Compton & Shim, 2015). Willenberg (2020) interviewed teenagers in Indonesia, and they emphasized the value of community involvement and volunteer work for their mental well-being. One teen stated specifically: “good mental health reflects good emotional control and good relationships and interactions with others” (Willenberg, 2020, p. 3). Qualities most important in friendships were mutual respect, trust, acceptance and protectiveness (Willenberg, 2020). In families, important relational qualities included supportiveness, empathy, honesty and an age-appropriate level of protection (Willenberg, 2020).

One risk determinant is that mental health disorders are highly stigmatized, being viewed as something that only other individuals experienced (Willenberg, 2020). Teens described individuals with poor mental health with negative and stereotypical qualities such as ““tattooed”, “malnourished”, “dirty”, “pale face”, “skinny”, “red eyes” and “not well groomed”; ““crazy”, “insane”, and “weak”” (Willenberg, 2020, p. 3). Also, Willenberg (2020)’s study found that another risk factor for mental health was bullying. Parents that put too much pressure on their children or exhibited uninvolved parenting styles were also mentioned as risk factors in some populations (Alegría et al., 2018; Willenberg, 2020).

Physical activity is another determinant of positive mental health (Orpana et al., 2016). Increased physical activity of any kind in humans, especially those experiencing mental health issues, is extremely beneficial in the promotion of positive mental health and is used as a coping mechanism and serves as hands-on, quality education (Penedoa & Dahn et al., 2005). People who regularly engage in physical activity had positive links to flourishing, emotional and social well-being (Beckervordersandforth, 2021). Sharma (2016) noted that exercising increases an individual’s cognition and self-esteem, while decreasing low mood. The promotion of exercise and physical activity is beneficial in achieving positive mental, physical, and emotional health outcomes across different cultural and socioeconomic populations. Research has been conducted to prove the benefits through randomized trials and promotion exercise that is directed at mental health (Penedo et al., 2005). Education on the importance of exercise for mental health can be promoted in various environments such as schools, communities, and workplaces, where poor mental health is more prevalent (Scheirer et al., 1995).

2.1.3 The Structural Determinants of Positive Mental Health

Structural determinants of mental health are similar to social determinants of health except they focus on larger factors including “the actions and norms of systems and policies”, that are much more difficult to change (Castillo et al., 2018, p. 1; Hastings et al., 2022). Examples include “economic, legal, political and healthcare systems”, and social hierarchies, present in schools, jobs, housing, prisons, hospitals and our climate (Castillo et al., 2018, p. 1; Hastings et al., 2022; Mariwala Health Initiative, 2021a). Societal norms refer to the “values, attitudes, impressions… biases… opinions… beliefs… [and] views” prevalent in society (Compton & Shim, 2015, p. 15). These affect health in similar ways as the social determinants of health, but the social determinants are more fluid and constantly changing whereas structural determinants rarely change (Hastings et al., 2022).

Walsh et al. (2022) highlights the need for changes in the structural determinants to help individuals have positive mental health:

“The path to flourishing is no simple issue of mind over matter. It also depends on society’s systems and structures: safe, affordable housing. A living wage. Solutions to systemic racism. Affordable, quality food and health care, including mental health care… It will take a lot more than simple activities to flourish. It will take structural change” (para 17-18).

Addressing the structural determinants of mental health begins with a focus on improving system inequalities (Mariwala Health Initiative, 2021a). Mariwala Health Initiative (2021a) states that these inequalities derive from “power relations that shape distribution of resources across communities and populations” (p. 6). Structural determinants can disproportionally affect racial, ethnic, gender and sexual minorities, and individuals living in countries with lower average incomes (Mariwala Health Initiative, 2021a).

One structural determinant is the economic policies surrounding universal healthcare. Publicly funded healthcare does not cover therapy by psychologists, causing individuals who cannot afford these costs to be unable to receive care (First Session, n.d.). While the structural determinants hold responsibility for creating many mental health inequalities, Mariwala Health Initiative (2021a) also reminds us of their ability to “reduce the risk of poor mental health as well as exert influence over the opportunities for care and support available to people across their life” (p. 5).

Creating interventions for the social and structural determinants of mental health can occur at an individual, community or structural level (Barry, 2000). These levels are similar to the levels described in the Socio-Ecological model of health promotion (see Figure 4) (Heise, 1999).

The individual level refers to intervening one person at a time (Barry, 2009). It follows a downstream approach, using strategies such as individual therapy (National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2014). Barry (2009) says: “there is a tendency to view mental health as an attribute of the individual, to emphasise the importance of more proximal psychological factors and in turn to underestimate the impact of the wider social and structural determinants” (p. 9). This individual approach is used less often in a mental health promotion approach because it uses a lot of resources to help very few people, making it less effective in helping the overall population (Frieden, 2010). However, the Mariwala Health Initiative (2021a) highlights the importance of these individual level interventions, because they connect to the larger social and structural determinants.

Community level interventions occur primarily at work, school and community centers (Barry, 2007). They can include support groups, education about mental health, or social groups to help build connections (Canadian Mental Health Association et al., n.d.). These are used in mental health promotion (MHP) because it takes fewer personal resources than the individual level and is easier to put in place compared to the structural level (Frieden, 2010; Hastings et al., 2022; McLeroy et al., 2003). These interventions are discussed in more detail in subsequent Chapters 6 (The Role of Community), 7 (School as a MHP Setting), and 8 (Work as a MHP Setting).

The structural level of intervention consists of making changes to policies and laws to reduce inequalities and better the mental health of many people (Barry, 2009). While these affect the population, it is also the most difficult intervention to put in place and normally takes lots of time, resources, and social capital (Barry, 2009).

2.1.4 The Interaction Between the Social and Structural Determinants

After understanding what the social and structural determinants are, it is important to consider how they intertwine with one another (Jeste & Pender, 2022). Compton and Shim (2020) this connection is evident because we see individuals in society being affected by more than one determinant at once. The benefit of this is that a single intervention can also address more than one determinant of mental health at once (Compton & Shim, 2020). An example that demonstrates how these determinants intertwine is nutrition in segregated areas. Research by Cotton and Shim (2022) shows that living in segregated areas puts families at a high risk of food insecurity, as a result of poverty and food deserts. Poverty is a social determinant of mental health by Compton and Shim (2015). Structural determinants are built by policies and those in power (Fang et al., 2021). The individuals in power have created these segregated areas and made them only livable to individuals on the lowest end of the income spectrum (Hastings et al., 2022). Children in these areas suffer from inferior education, because of limited funding (Cotton & Shim, 2022). This leads to lack of education on general school curriculum and students’ understanding of health literacy and behaviors that enhance their health due to less staff, therefore overcrowding in classrooms (Cotton & Shim, 2022). These behaviors also indirectly affect other determinants including employment and income, which can have life-long effects on an individual’s mental health (Cotton & Shim, 2022).

Figure 8 shows the existing relationships between the social and structural determinants of health (Compton & Shim, 2015, figure 1-1; Compton & Shim, 2020, figure 1; Orpana, 2016, figure 1). The structural determinants are in the purple boxes (societal norms; public policy; economy; healthcare, legal and political systems), and the social determinants are in the green and red boxes (determinants listed in figure 7 and healthcare access) (Compton & Shim, 2015, figure 1-1; Compton & Shim, 2020, figure 1; Orpana, 2016, figure 1). Figure 8 also demonstrates that the structural determinants lead to unfair advantages toward some individuals, causing differences in the opportunities an individual has (pink box) (Compton & Shim, 2015). The yellow boxes (healthy options, behavioral risk factors, choices and actions, psychological stress) refer to the indirect consequences of the social and structural determinants, which have a direct effect on an individual’s mental health (Compton & Shim, 2015, figure 1-1; Compton & Shim, 2020, figure 1).

Figure 8: Model of the existing relationships between the Social and Structural Determinants of Mental Health. This figure was created by combining information in the models by Compton and Shim (2015, figure 1-1), Compton and Shim (2020, figure 1) and Orpana (2016, figure 1).

In this section, we have learned about key social determinants of mental health. While having poor social determinants of mental health can lead to increased susceptibility to mental health issues, poor structural determinants (which are biased towards some groups of people) can reduce the chances can individual will receive quality mental health treatment.

2.2 GAPS AND LIMITATIONS

In this section we will touch on the gaps in mental health research, including a lack of research on positive mental health, underrepresented populations, and limitations of using a westernized definition of well-being.

2.2.1 Lack of Research on Determinants of Positive Mental Health

Huppert & Whittington (2003) state that mental health comprises mental ill-health and positive mental health, two separate constructs. One gap in current evidence of the social and structural determinants of mental health is the limited research about the determinants of positive mental health. Most mental health research focuses on risk factors for poor mental health, instead of protective factors that make up positive mental health (Orpana et al., 2016). After reviewing 88 studies related to mental health, Orpana et al. (2016) found that the majority had a connection to mental illness, and none were exclusively about positive mental health. In 2013, the public health surveillance agency’s only surveillance system for mental health was for mental illness (Orpana et al., 2016). The agency created a framework to patch this hole in existing research, so interventions could focus on improving positive, not only treating poor mental health (Orpana et al., 2016).

This gap is also evident in many national health surveys put out to the public, with many covering only a small number of determinants related to positive mental health (Dreger et al., 2014). From this, researchers cannot determine how indicators of positive mental health appear during different stages of life (Dreger et al., 2014). Dreger et al. (2014) was one of the first studies to incorporate questions about determinants of positive mental health (“sociodemographic, psychosocial, and material factors”) into their survey (p. 2).

However, there are also limitations to Dreger et al. (2014)’s study. Using a cross-sectional research method (researchers collect data from different aged participants at one time point) means that the authors cannot conclude how or whether the determinants of positive mental health found will change over time (Dreger et al., 2014). Researchers are also unable to infer causation (whether one determinant causes positive mental health), they can only indicate whether a determinant is associated with positive mental health (Dreger et al., 2014).

There are limitations to the population Dreger et al. (2014) use in their study. Although the sample of participants was selected using random sampling, the biggest concern was that only 41% of participants selected to participate completed the interview (EQLS survey) (Dreger et al., 2014). This selection bias could mean that individuals with poor positive mental health or additional barriers may not have responded, meaning the results may not truly represent the general population (Dreger et al., 2014).

2.2.2 The Determinants of Positive Mental Health May Apply Differently to Less Researched Populations

The existing research also has gaps in how the determinants of positive mental health will apply to less researched populations. One group that this is particularly evident in is youth. Children may have different determinants of positive mental health than adults, making it challenging to include all age groups in one framework (Orpana et al., 2016). The Public Health Surveillance Agency created a separate framework for children and teens. However, Orpana et al. (2016) reported that it is still in progress (while the adult framework is complete). This limited data makes it difficult to create frameworks and tools specifically for youth and children, as different indicators may be present throughout an individual’s life course (Orpana et al., 2016).

Barry (2009) states that greater investigation is required into the relative effects of material resources, social capital, and psychosocial elements, as well as how these factors combine to affect the mental health and wellbeing of populations and people. This is evident in reference to socioeconomic status. Poor mental health is linked to low socioeconomic status, and low socioeconomic status is also linked to lower levels of education (Barry, 2009). The problem is that if a community does not have access to higher levels of education, it is difficult to obtain the professionals needed to improve policies for positive mental health (Barry, 2009).

There is also limited research on the behavioural determinants of mental health. Behavioural factors, such as physical activity, may indirectly affect positive mental health but were not researched in any of these studies (Dreger et al., 2014). There is a need to further investigate the relationship between the resources an individual has access to and positive mental health (Dreger et al., 2014). For instance, physical activity is a determinant of positive mental health (Orpana et al., 2016). However, living in a high-risk neighbourhood could decrease their access to play outside safely (Dreger et al., 2014). Dreger et al. (2014) state that studying behavioural factors would be a valuable topic for future research.

2.2.3 Positive Mental Health is Defined Differently Cross-Culturally

It is also a critical limitation that our determinants of mental health are based on a Western definition of mental health. What is viewed as making up positive mental health in one culture may not make up positive mental health in another culture. Ideas of positive functioning, beliefs surrounding illness, acceptable behaviours, and societal norms vary; this suggests the need for cross-cultural perspectives and may constitute a gap within already limited available data sources. Much of the research highlighted in these articles includes research in North American and European nations and does not give an overview of global population mental health.

In this section we have learned that existing research places emphasis on poor, and not positive mental health, and research methods lack the ability to demonstrate which determinants that cause positive mental health.

2.3 FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

This section covers how we can further research on the determinants of mental health, by creating a universal definition of mental health, studying the relationship between the social and structural determinants, and improving existing frameworks.

2.3.1 Introduction

Social and structural determinants of mental health often go hand-in-hand with one another because social determinants are often dependent on the structures in society (Compton & Shim, 2015). Social determinants of mental health are considered to be societal matters that affect one’s mental health in a positive or negative way (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2010). In Canada, social determinants of mental health are freedom of discrimination, social inclusion, and access to economic resources (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2010). In contrast, structural determinants of mental health refer to policies and programs in place for citizens (Compton & Shim, 2015). Both determinants play a large role in a person’s quality of life, therefore research into new areas must be developed so individuals can flourish. In addition, previously developed areas must be refreshed to keep the past work current. Throughout this section of the chapter these areas will be discussed. As well as how social and structural determinants intertwine, and the role that MHP plays in educating individuals on upstream approaches to their mental health. However, creating a generally agreed upon definition of mental health is the first discussion.

2.3.2 Defining Mental Health:

A first step in furthering research in the field of MHP, and better understanding the determinants of mental health is to create a definition of mental health that can be universally agreed upon. To date, multiple definitions of mental health exist; such as the

World Health Organization (WHO), stating that mental health is “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (World Health Organization, 2022). In comparison, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) defines mental health as “the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, inter connections[,] and personal dignity.” (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014). In PHAC’s definition of mental health it takes into account mental health and mental illness, whereas the WHO’s definition is from a more positive perspective. Revising the WHO’s definition is beneficial as their current definition measures the concepts of mental health such as resilience, rather than the determinants of mental health (Barry, 2009). This is problematic because measuring the concepts of mental health assumes that cultures have the same values, norms, and social influences, when they may be very different (Barry 2009). These factors ultimately lead to variation amongst definitions across current research, leading to different factors of mental health being measured, therefore potentially skewing results. An example of this is the Orpana 2016 model (Figure 6). Their model is based on Western ideologies. Although this model was built for Canadian citizens, it does not take into account newcomers to Canada. Future work must define mental health before building a model to avoid inconsistencies in research.

The inconsistencies between definitions are thought to be the result of a lack of theory related to mental health and mental illness (Kelloway et al., 2023). Incorporating more theory when defining mental health will keep the definition well-rounded by recognizing that mental health is a continuum and looks different for every person (WHO, 2022). Building off of models such as Keyes’ Dual Continuum Model, (Figure X) recognizes that while someone has a low mental illness they are still able to languish, or while one has high mental illness they are still capable of flourishing (Keyes, 2002). Recognizing that not every society has the same needs and that individuals may still be doing well in some aspects of life while languishing in others is vital to acknowledge when defining mental health.

Figure 9 : Keyes’ Dual Continuum Model (MHW Advisory Groups, 2020)

2.3.3 Confounding Variables in the Determinants of Mental Health:

To improve upon the negative effects of poor social and structural determinants of mental health, research must study prevention efforts for confounding determinants (Braveman & Gottlieb, 2014). In psychology, confounding variables refer to variables that are not being studied, but influence the variable that is being studied (Thomas, 2020). Therefore, in this case, a confounding determinant would refer to a social or structural determinant that was not measured, but was influencing mental health (Thomas, 2020). These variables can be misleading, because results can appear as if the determinant being measured is affecting mental health, when in reality it is not (Thomas, 2020). This calls for more sound and robust research methods that take confounding variables into account (Thomas, 2020). There also needs to be greater diversity in research methods used, such as integrating longitudinal studies, pragmatic trials and cost-effectiveness analyses (Alegría et al., 2019). Alegría et al. (2019) indicate one limitation of existing research is that “[m]any social determinant studies have used cross-sectional designs that fail to account for temporal trends and cumulative effects [114], and many have failed to include control groups or address selection bias” (p. 9).

Research then must explore relationships between different determinants to identify other high-risk groups lie (Sowden et al., 2017). For example, children in segregated areas and the Métis are considered high-risk groups because there is a current lack of research on them (Nelson, 2013). Research should strive to positively impact all members of the population, so it is important to consider how some study results (ex: high-risk groups) could be used to stigmatize groups, and take measures to reduce this (Alegría et al., 2019). It is important to study how the social and structural determinants affect different populations and life stages to determine how and when interventions will be most effective (Alegría et al., 2019). Similarly, there must be more detailed research looking at how specifically the determinants interaction, not just that they do (Alegría et al., 2019). Alegría et al. (2019) suggests that one way to study more connections between social and structural determinants is by using simulations, and that all research should use many different types of data.

When exploring determinants, it’s imperative research be done from a MHP perspective; not a psychology or health promotion perspective (Dreger et al., 2014). This is important because researching confounding variables from a psychology perspective looks at downstream approaches rather than a preventative (upstream approach) (Dreger et al., 2014). Since social and structural determinants impact the entire population, policy changes need to be guided by the needs of the entire population (Alegría et al., 2019). Research that guides these policies should come from identified population inequalities, not from the vulnerabilities that occur in a small subset of individuals (Alegría et al., 2019).

2.3.4 Improving Past Frameworks:

As our society continues to evolve, the social determinants of mental health may change, and frameworks will need to be updated to fit these new determinants. An example of a current framework needing an improvement is the Orpana 2016 framework (Figure 7) as it is missing social media as a determinant. Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic, online platforms (ex. TikTok) have become extremely popular worldwide (Molla, 2021), therefore researching social media as a determinant is a consideration when revising the current framework. In comparison, the more recent Willenberg 2020 model includes social media as a determinant of mental health for Indonesian youth as it is a space used for cyberbullying (Willenberg et al., 2020). To reduce this risk participants recommended limiting time spent on social media (Willenberg et al., 2020). To improve on the current frameworks, researchers may use historical data (Orpana et al., 2016) and monitor indicators based on other researchers’ frameworks to address potential data gaps.

2.3.5 Early Intervention:

Furthermore, promoting mental health requires research to find the most effective way of introducing it early in the lives of youth and young adults. Adding mental health studies into the school curriculum may be a method to use so the term is neutralized. However, this area needs to be researched to determine the outcome. In adults, bringing mental health education into part of general job education is shown to be beneficial (Kelloway et al., 2023). Research shows if employees know that they will be supported by their leaders for taking time off due to mental illness the long-term effects are less severe (Kelloway et al., 2023). This is exemplified by destigmatizing workplace absences or modifications so employees feel they can ask for help right away and be accommodated for, rather than later (Kelloway et al., 2023). These measures can decrease employer spendings on longer leaves of absence as well as benefit the employee as a consistent job gives them consistent income, thus better mental health.

2.3.6 Conclusion:

Future research into the social and structural determinants of mental health must be flexible; it must create a foundation by defining mental health, as well as make slight distinctions between programs for different groups. Researchers must display their work so the general public will be able to understand and implement it; specifically, when promoting an upstream approach to mental health.

In this section we have studied how universal determinants of mental health cannot be created without a universal definition, and mental health frameworks need to be continually updated as society changes to incorporate the new needs of the population.