3 INFORMING PROGRAMS AND POLICY

Chloe McDermott; Emily Mannella; and Trent Nadin

One way individuals can take care their well-being is by attending mental health programs. In this chapter, we will discuss how these programs, and their policies can be informed by mental health theory.

3.1 KEY THEMES AND MAIN IDEAS

A key action in mental health promotion (MHP) is informing practices and the implementation of programs. Research generates and evaluates evidence on MHP across contexts such as environments (i.e., schools, communities, work settings) and socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., culture, age, gender).

3.1.1 What is Effective Mental Health Promotion?

Designing a comprehensive strategy for the promotion of mental health is most efficient when strategies, ideologies, and values are developed by people who have applicable real-world experience (Jane-Llopis & Barry, 2005). Specifically, MHP programs at home, school and work have benefited from using the experiences of various stakeholders (e.g. policymakers, researchers, implementers) in their designs. This settings-based approach creates supportive environments for health development, as environments such as home life, workplaces, schools, and communities, along with a variety of cultural settings are crucial settings for effective interventions as they address the core determinants of MHP (Jane-Llopis & Barry, 2005). To inform programs and policy, clear frameworks, settings-specific approaches, and efficacy need to be considered.

Frameworks

Developing a proper framework leads to efficient interventions that show an overall improvement in mental health in adolescents through to adults in the workplace, schools, communities, and in home-based settings (Jane-Llopis & Barry, 2005). An organized framework advances and develops a comprehensive strategic approach to health promotion that can be adopted and implemented across many environments tailored to a specific demographic. Furthermore, the use of appropriate evaluation methods and research frameworks that are based solely on knowledge translation and evidence-based approaches are able to distinguish the intricacy, rights and wrongs of existing interventions and/or practices (Jane-Llopis & Barry, 2005).

3.1.2 Evidence-Based Approaches

To ensure the proper implementation of an intervention, it is required to adopt different evidence-based approaches (EBAs) in order to generate the desired measurable outcomes. Evidence-based approaches (EBAs) refer to interventions and policies that are guided by research findings, to provide the most effective outcomes for their intended audience (Drake et al., 2001; Vandiver, 2009). Drake et al. (2001) refer to EBAs as the base layer of mental health services and clarifies their importance: “given that mental health resources are limited persons…. have a right to have access to interventions that are known to be effective” (p. 180). Barry and Jenkins (2007) show that the importance of EBAs is different to different stakeholders. First, EBAs help hold mental health government budgets accountable and provide clarity on the outcomes of their expenses (Vandiver, 2009). EBAs are relevant to the field of mental health promotion because their research has the potential to focus on the holistic view of mental health in relation to the whole person (Drake et al., 2001). Specifically, a wider research lens helps move past the downstream approach of providing treatment to decrease the risk of relapse, towards an upstream approach that focuses on mental health in all aspects of one’s life- their work, relationships, independence, and beyond (Drake et al., 2001). To mental health professionals, EBAs increase their confidence of the interventions having the most effective impact on the population (Barry & Jenkins, 2007). This also increases the confidence of participants, as they have evidence to trust the programs’ effectiveness (Barry & Jenkins, 2007).

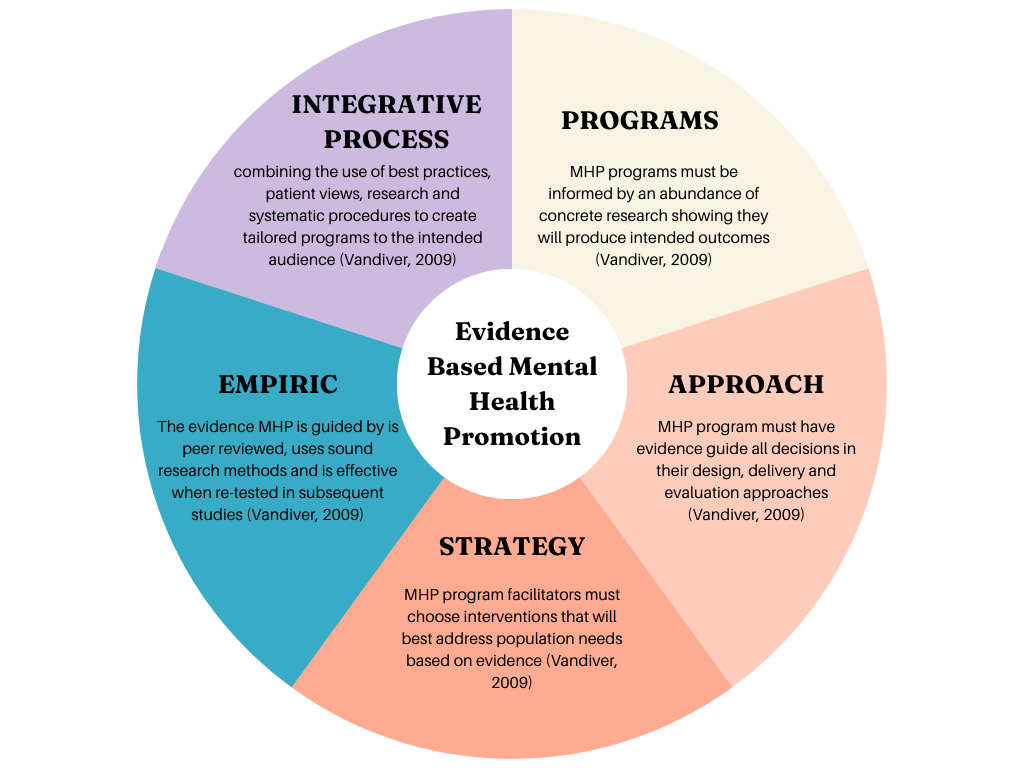

Vandiver (2009) shows EBAs can be defined using five slightly different qualities- integrative process, programs, approach, strategy and empiric-each impacting different elements of the health promotion process. Figure 10 shows how these elements can be modified to fit the MHP scope (Vandiver, 2009). Notice how there is much overlap between each element, showing having sound evidence informed by good quality research methods is the key to successful MHP programs and policies (Vandiver, 2009).

Figure 10: The 5 components of Evidence-Based Mental Health Promotion (Vandiver, 2009).

3.1.3 Knowledge Translation

Examining research in the field of mental health in order to advance the development of knowledge translation is for successful program implementation (essential and effective) (Goldner et al., 2011). Knowledge translation (KT) is a key component to program implementation, evaluation, and replication/adoption. CanChild (n.d.) says KT “is a complex, two-way process between those who develop the knowledge and those who will use the knowledge” (para 1). In an article presented by Goldner, it is shown that KT efforts are deemed a very important part of the field of MHP promotion – especially in areas of research, policy, and practice (2011). This review examines research in order to advance the development of KT by helping inform the development of a Knowledge Exchange Centre initiated by the Mental Health Commission of Canada. This knowledge exchange center constitutes a key initiative that will bring action aimed at achieving improvements to mental health initiatives in Canada (Goldner, 2011). Improving the KT between stakeholders, policymakers, and researchers significantly increases a successful program implementation, ultimately producing successful program evaluations and outcomes. KT is not simply applying any research to any program (Barry & Jenkins, 2007). Effective KT requires careful determination of which EBAs best suit MHP research, and which methods with reach the needs of the general population (Barry & Jenkins, 2007).

Previous Research and Applicable Research

Research of knowledge translation in areas of mental health have been very limited and confined to health organizations in Canada and a few key researchers. There has been an exponential peak in interest and publications that are focused on KT in mental health initiatives which have sparked some awareness in recent years, growing the conversation. Many of the KT interventions seek to enhance mental health care services and improve the outcomes of mental health disorders. Knowledge translation in MHP generally addresses the translation of scientific evidence; being translated to social media, marketing campaigns, and websites (Goldner, 2011). Being able to effectively communicate program design, implementation, adoption strategies, evaluation needs, and program efficacy across all sectors and from previous research is crucial for a successful intervention. In order to do this, relationships between researchers, policymakers, stakeholders, implementers, and evaluators need to be strong enough to effectively communicate knowledge for a successful intervention overall.

3.1.4 The Implementation of Mental Health Promotion Programmes

How Research of EBAs can inform Program Implementation

Barry and Jenkins (2007) state “implementation turns theory and ideas into practice and translates design into effectively operating programmes” (p. 48). The existing challenge is that we are seeing a gap between mental health research findings, and the strategies being used in programs, indicating the need for more EBAs in mental health programs and policies (Vandiver, 2009).

The implementation of an effective intervention or program consists of more than just program content and how it is delivered (Barry, 2005). Successful implementation relies upon the quality of a program and strong efficacy evidence. Program implementations become a challenge when implementation is not researched, reported or not evaluated properly. One issue in mental health promotion research is that the majority of studies focus on mental illness, not mental health (Vandiver, 2009). This has created an abundance of EBAs for clinical treatments, and a lack of EBAs on positive mental health and the social and structural determinants (Vandiver, 2009). Data collection on program implementation is advancing knowledge as it relays crucial information for replication in an applicable setting (Barry, 2005). This data collection is also very important for adoption in other socioeconomic settings, such as low to middle-income countries (Barry & Jenkins, 2007). In contrast to perceptions that EBAs cannot be implemented because of community and participant differences, Drake et al. (2001) indicates that the more a program follows the same principles of an EBA, the more it will produce similar outcomes, regardless of community circumstances.

How to we determine what research can inform EBAs? There are many different ways to assess the quality of research, to determine whether it can be used in EBAs (Drake et al., 2001). Drake et al. (2001) says the best evidence comes from randomized controlled trials, because individuals can be randomly assigned to groups, and they can therefore compare intervention to no intervention, or alternative interventions. However, in the field of mental health promotion, randomized controlled trials are not used very often, because of the focus on population health, in comparison to treating individuals (Vandiver, 2009). Individuals cannot be randomly assigned to the social and structural determinants of mental health, preventing randomized controlled trials from being used (Dalhousie University Introduction to Psychology and Neuroscience Team, n.d.). In these cases, Drake et al. (2001) recommends informing EBAs from quasi-experimental studies. EBAs should not be based on research from open clinical trials and clinical observations because they are informed with opinion, and therefore have a higher risk of containing researcher bias (Drake et al., 2001). Some agencies sort these types of research into levels of evidence quality (ex: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality), some use expert consensus (ex: Triuniversity consortium), and others have specific guidelines that research designs must meet (Drake et al., 2001).

The Implementation Process:

The implementation of a program has room to be influenced by the delivery, target audience, and program responsiveness (Barry et al., 2005). Quality and quantity can affect the behaviours to which the program is responded (Barry et al., 2005). Participants are more likely to give the same energy back that was given to them by program implementers (Barry et al., 2005; Barry & Jenkins, 2007; Jane-Llopis & Barry, 2005).

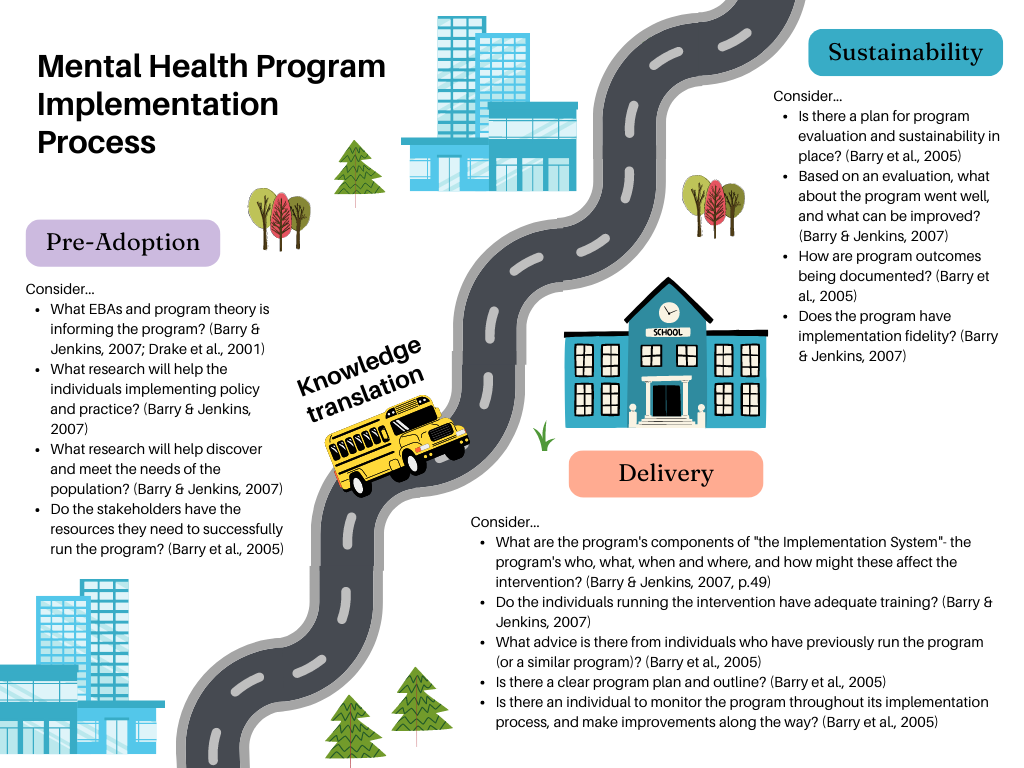

The MHP programs implementation process strives to adapt to the fundamental principles that are outlined in the Ottawa Charter, by delivering programs in a collective, empowering, and interactive way (Barry et al., 2005). There are three phases that are recommended for the improvement of program implementation for MHP (Barry et al., 2005). These three phases are the pre-adoption phase, delivery phase, and sustainability phase (Barry et al., 2005). Some key components the pre-adoption phase consists of are assessing available resources, identifying the main problem with the protective and risk factors it is associated with, ensuring the program is appropriate for the target audience and planning for long-term success (Barry et al., 2005). The delivery phase consists of assessing the preparedness of intervention in the applicable setting, using evidence-based theories and interventions, modifying to fit needs, providing a detailed framework, providing support and partnering with an evaluator (Barry et al., 2005). Lastly, the sustainability phase aims at developing a framework to ensure the program is feasible and can last long-term (Barry et al., 2005). The sustainability phase uses the documentation information from the implementation and delivery phase in order to adapt and process the data to continuously make changes that best suit the environment in which the intervention is being held (Barry et al., 2005).

Figure 11 uses an example of a school mental health promotion program, showing considerations for the pre-adoption, delivery and sustainability phases (Barry et al., 2005). Knowledge translation is represented by a school bus to demonstrate how it is the connection between the research evidence (EBAs) and the interventions used in programs (CanChild, n.d.).

Figure 11: The MHP Program Implementation Process: Pre-Adoption, Delivery, Sustainability (Barry et al., 2005; Barry & Jenkins, 2007; CanChild, n.d.; Drake et al., 2001)

3.1.5 Evaluation

Llopis and colleagues (2005) show us that programs and policies have the ability to produce mass change when there is efficient program design, evaluation, implementation, and assessment. Program evaluation and assessment are capable of pinpointing mediating variables, that can produce change at many different levels of the program. Being able to identify these benefits as a result of these changes can, in turn, produce programs that are effective, feasible, and sustainable across multiple settings, increasing efficacy (Jane-Llopis & Barry, 2005). Evaluation allows us to “improve our understanding of how a programme achieves what it does” (Barry & Jenkins, 2007, p. 72). It facilitates KT, and allows best-practices in MHP to be developed and shared (Barry & Jenkins, 2007).

Specific evaluation techniques rely on detailed program explanation, reliable documentation, and program monitoring (Barry et al., 2005). Barry et al. (2005) explains this happens to evaluate the quality and the quantity of the program implementation which is necessary to understand how the programs work, why they work, the program’s strengths and weaknesses, and to provide feedback to ensure quality improvement during the implementation process.

An important factor to measure when evaluating programs is implementation integrity (the amount of the designed program that is actually being implemented) (Barry & Jenkins, 2007). The level of implementation integrity depends on a program’s consistency between its design and delivery, the quality of its delivery, how well participants are engaged in the program, and the program timeline (Barry & Jenkins, 2007). When an evaluator assesses the positive and negative results from a program, compared to the implementation integrity, it eliminates the risk of incorrectly attributing the wrong cause to outcome (Barry & Jenkins, 2007). For instance, negative program results do not always mean the program not effective (Barry & Jenkins, 2007). Barry and Jenkins (2007) indicate that evaluation efforts should study: systems to monitor population mental health, results of applying interventions to alternative populations, and the results of interventions both in “real world” and research conditions. Through generating EBAs, research aids the implementation of MHP programs and policies (Barry & Jenkins, 2007). MHP as a whole is concerned with the implementation process, as well as the evaluation and outcomes.

This section has discussed how effective programs must build upon knowledge translation of existing research, take account for personal experiences, and focus on long-term sustainability.

3.2 GAPS AND LIMITATIONS

In this section we will study the limitations in existing program and policy research, such as the lack of program transferability from one population to another and lack of resources to sustain effective programs.

3.2.1 Lack of Consensus on Evidence-Based Approaches

One existing problem for informing programs and policies, is that there is a lack of consensus on the definition of “evidence” (Barry & Jenkins, 2007). With researchers in disunity over this term, it creates even larger problems when trying to agree on evidence-based approaches (EBAs). Barry and Jenkins (2007) state that researchers need to determine “how best to respond to the challenge of assembling evidence in ways which are relevant to the complexities of contemporary health promotion” (p. 29).

3.2.2 Specific Populations Require Unique Modifications

MHP promotion programs designed for specific populations have difficulty being sustainable and transferable to other populations (Barry & Jenkins, 2007; Drake et al., 2001). Programs designed for low-income populations can have difficulty adapting to recreating the program to apply to other populations (Barry & Jenkins, 2007; Drake et al., 2001). An example would be programs designed for less educated populations that must be adjusted for other populations with higher academic standings.

Low-income Populations

Kopinack (2015) studied the implementation of a Western-oriented mental health systems in different cultures, specifically in Uganda. The national government recognized the challenges faced in mental health services in developing countries showing that it poses serious public health and development concerns. The Uganda Health Services Strategic Plan states their main challenges in the mental health system as limited access, poor referral systems, lack of skilled staff and more (Kopinack, 2015). As more countries start introducing Western medicine, cultural bias must be considered. It focuses on values, beliefs, resiliency, health promotion, and recovery. Implementing Western medicine in developing countries will be slow and gradual; however, it will improve mental health systems’ efficiency, providing improved care, better outcomes, and overall quality of life (Kopinak, 2015).

3.2.3 Programs Expenses and Limited Resources

MHP programs and interventions have many direct and indirect costs, requiring strategies to secure and manage funding (World Health Organization, 2004). Support and research efforts toward MHP are growing, however, more resources are necessary to be effective (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2019). EBAs unique to a specific population are needed; however, there are limited resources to properly support, assess and implement these programs (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2019). Jane-Llopis et al. (2005) discuss the combination of long-term research-based results with diverse community needs and resources that make applying policies difficult and expensive.

Another limitation of program design is the cost-benefit analysis, as presented by Jane-Llopis et al. (2005). Depending on the population, program delivery can cost more than other populations with an equal or less desired outcome compared to other populations. Ensuring that the cost put into the program produces significant results will be important. If two populations have the same MHP program cost, but one population benefits less from it, this population will see fewer results regarding improved mental health. For this population, the minimal program benefits may not be worth the cost of the program. Rickwood (2001) found an association between poor mental health and low-income countries, indicating the need to provide improved mental health programs and policies.

The cost-benefit analysis for MHP programming is lacking. The cost outweighs the outcome benefits to meet the needs of the target population, delivery, resources, and structure. Rickwood (2011) examines a population that is understudied heavily: youth and young adults. Researching this population will be expensive and time-consuming. For instance, at the beginning of 2021, the Government of Canada put $100 million dollars toward mental health promotion and mental illness prevention (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2023).

Moreover, intended outcomes vary from population to population, making calculating the cost-benefit ratio difficult. Goldner et al. (2011) describe actions that can be made, such as increasing publications that seek to enhance mental health, address knowledge translation (KT) in scientific evidence and improve KT between stakeholders. Barry & Jenkins (2007) suggest that this calls for the creation of more methods and frameworks to evaluate research and develop more EBAs.

This section has mentioned that the benefits of mental health programs need to outweigh their costs for resources, which is especially important in low-income populations.

3.3 FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

The implementation of mental health promotion is what will determine the success and effectiveness of mental health programs because of the people they can reach. The implementation process of creating a program is the most important part because, without a framework plan for the future direction of the program, it will not be sustainable. Mental health promotion programs research has shown increasingly positive results in attracting individuals to seek youth or resources. Additionally, there has also been research addressing the factors of poor framework and the capability of creating a program that is sustainable enough to make a large impact in schools, communities or individuals’ homes. Implementation is an essential part of mental health programs and the effectiveness that mental health promotion can give. It shows the importance regarding the future direction of research in implementation. Research is needed for the implementation of MHP on the need for practice and policy guidelines based on effective available evidence considering all critical factors that will better the program and process of effectiveness (e.g., schools, communities, homelife).

3.3.1 Economic Settings

Increasing the replication and effectiveness across a range of cultural and economic settings to ensure the implementation is successful but also provide widespread dissemination in the “real” world settings. Cultural and economic settings are a large contributor to how mental health promotion programs will be seen and effective, as all different individuals are able to have access to them. This is followed by the facing challenges of trying to implement and collect evaluations in less developed countries where there are fewer resources and support (Barry et al., 2005). The importance of evaluation findings in this sensitive section regarding mental health promotion programs plays a critical role in demonstrating the potential to provide funding and sustain long-term in less developing countries (Barry et al., 2005). This will also give insight into the outlook of widespread dissemination regarding the “real world” settings and ensure that the strategies being implemented are directed at certain needs and appropriate to the audience. Future research will then ensure different knowledge and skills of evaluation for the onset of mental health that is developed in different settings through different opportunities. Research has shown that keeping an agenda is important to sustain a program but also involves administering an approach to connect with the embraced community that is in need of help (Dadds et al., 2001). This article also touches on the factors of allowing for short-term strategies to be introduced until the program has adapted to the setting and then deciding on long-term strategies to build for the future (Dadds et al., 2001). Another research article suggests that positive effects have come from an amplified intervention that targets multiple negative barriers from different domains (individual environments, school, home) (Kiselica et al., 2001). Future research within economic settings should reflect on overcoming the barriers of implementing mental health promotion in lower unsupportive settings that need more help. Creating an agenda will allow for better success of this strategy.

3.3.2 Evaluation of Cross-Fertilisation

Identifying program-specific outcomes in MHP from evaluation in different settings and stimulating cross-fertilization in order to connect existing programmes. This will help to increase efficiency (e.g., programs like the world health organization or Healthy Cities project) around operational partners who can help to address social determinants of health and public health needs that are essential to people (WHO, 2023). Examining other previous programs around mental health and determining ways for future improvement based on the fails or issues that were done by other programs. It is important to address previously made mistakes regarding sustainability or strategies so that they are not repeated. Evaluation can save numerous amounts of time and energy, as it provides a guide of the things that will make and break the program but also will give an opportunity for individuals to express how they felt. Examining the intent of program integrity more in the future will allow for more evaluation from both primary and secondary analysis (Dane et a., 1998). This will create program intent and a planned route through detailed evaluation, creating more opportunities for new ideas and resources for the future but also limiting the ongoing research being done that is useless to mental health promotion program contribution (Dane et a., 1998). Program delivery should be based on past evaluations and also be completed in the process of any ongoing mental health programs to ensure the right target audience resources are being provided with consistently changing dynamics.

3.3.3 Long-Term Follow-Ups

Include long-term follow-ups of evaluation and the organizational structures of policies that will support the long-term goals of MHP implementation to create sustainability. Well, future research includes program evaluation, it should also include long-term follow-ups as this will allow sufficient time for interventions to show their effects. Long-term follow-ups in the future will provide a more accurate estimation of the duration of effects and help determine other individuals’ paths of support for mental health through the program (Herman et al., 2005). Adding more attention to long-term follow-ups in the future can create and reflect the reality of how the program works and the effects it has (Herman et al., 2005). This will also create more influence and promote the intervention of mental health in the proper settings.

3.3.4 Improved Knowledge Translation

Studies has not been able to demonstrate the long-term benefits of KT in MHP due to the lack of research presented on this topic, even with the current effective research that has provided important connections. Future research on involvement in the function of knowledge translation within MHP will address stakeholders and the numerous benefits. These numerous benefits are not known to many as there is a lack of KT in many program settings when it is a strategy that can be very helpful. As of now, there is limited research on how knowledge translation can be used but also how it can possibly affect mental health promotion. Knowledge exchange can be challenging as there are many areas to consider, and it allows for a progressively broader perspective, incorporating a wider range of participants and increased knowledge. Knowledge translation can give experiential knowledge that will ease the building process of a program and also help to understand the contexts of mental health in a structured way.

3.3.5 Targeting Decision-Making

Targeting the efforts to include more knowledge translation in the implementation of MHP to ensure that logical effective frameworks are being used and demonstrate shared decision-making for future programs. Knowledge translation is a great tool to include when developing a framework and targeting a certain topic of interest. More research was developed regarding the process of KT around how it can make the process of program implementation more successful but also how it can bring more attention and result in better outcomes. Logical effective frameworks that contribute to all individual needs and ideas can be done using knowledge translation as it can generate ideas around shared opinions but also apply guidelines to stick to an agenda. An article presented by Elliot Goldner states that knowledge translation can keep MHP accountable for sticking to their frameworks and meeting the requirements that are needed for mental health support. Healthcare institutions have started to look into the future direction of knowledge translation because it is known to be consistent and apply accurate knowledge when in a workplace environment (Goldner, 2011). Future implementation and knowledge around including shared decision-making through KT will measure the effectiveness and determine further ideas when creating support for mental health (Dane et al., 1998).

3.3.6 Participatory Research

Conducting more participatory research on KT surrounding evaluation of the benefits that have been inflicted on MHP to provide more resources for new incoming implementation programs that present logical strategies. Participatory research can also test for new building strategies in different settings in order to determine if they should be introduced as a mechanism or treatment. This direction of future participatory research is also acting on change and growth in mental health, creating new ways that will seek answers for those with mental health. Additionally, it is important to include new growing populations and cultural assets that are evolving, and this research can also help to provide updated status on different setting approaches to appeal to. Measuring the implementation processed within programs for mental health is important, as keeping all working fields on the same page (Scheirer et al., 1995). Combining roles as researchers and gathering relevant valid information that can be used for evaluation or data, is a way to of showing how KT is involved (Scheirer et al., 1995). Measuring future approaches through participatory research could create breakthroughs in MHP programs.