1 INTRODUCTION TO MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION

Alanna Kaser and Megan Sponagle

1.1 HISTORY OF MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION: MENTAL HEALTH VS. MENTAL ILL-HEALTH

1.1.1 Introduction

It is recognized that mental health is an inherent and central component of health and that promoting mental health optimizes our quality of life. In fact, mental health promotion has grown into a key field of health promotion research and programming, as well as a key priority in building thriving individuals, communities, and populations. However, recognition of mental health within the field of health promotion and the emergence of mental health promotion as its own distinct domain was delayed in part, by evolving perspectives and definitions of mental health and its scope of relevance. Understanding a brief history of the conceptualization of mental health is central to the evolution of mental health promotion and how it is widely understood and studied today.

1.1.2 Early Origins: Mental-Ill Health & Mental Illness

Early understandings and study of mental health existed within the domains of psychology and psychiatry, resulting in an approach focused on the treatment and prevention of mental illness at an individual level (Bertolote, 2008; Froh, 2004). By consequence, having “good” mental health was understood to be simply the absence of mental illness (Keyes, 2002). This was achieved and relevant only through a treatment lens, for individuals with existing mental health disorders. Eventually, this perspective expanded to include preventive approaches which identified and targeted risk factors to prevent poor mental health (i.e., the risk-reduction model). Fortunately, the utility of preventive approaches to extend beyond the individual-level (e.g., community programs, prevention policy) and the efficacy and reduced burdens available in seeking to prevent, instead of only treating mental health challenges enforced the recognition of protecting mental health as a key matter of public health. In 2001, the WHO published a report emphasizing the importance of addressing mental health on a global level and clarified the importance of the topic as a matter of public health. The report acknowledged mental health as having equal importance and interconnectedness with physical health, as well as, outlined its vital contributions to well-being, at and beyond the individual-level (WHO, 2001). However, the underlying view of mental health as solely the absence of illness and the dominant focus on treating and preventing mental disorders still informed the predominant prevention and treatment-based actions recommended within both programming and policy.

1.1.3 Influences from other disciplines: The paradigm shift in studying mental health

The paradigm shift towards a positive approach to mental health and its promotion was informed in part by health promotion and population/public health domains, but also by the fields of positive and community psychology. Although the views of more holistic and less-negative versions of mental health date back to the mid-1950s, the diseased-focused perspective of mental health remained dominant until positive psychology gained traction in the early-2000s. Positive psychology shifted focus towards identifying and promoting beneficial and strengthening factors that enhance people’s mental health and their overall quality of life, but the field remains largely focused on the individual (Froh, 2004; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Community psychology functions to advance well‐being at multiple levels (i.e., individual, organizational, and community levels) to foster social change (Neigher et al., 2011). Therefore, contributions from community psychology have extended the promotion and positive-enhancement approach beyond the individual-level. Early research in these fields demonstrated that the enhancement of positive health-related factors can not only improve and prevent both mental and physical health challenges, but also enhance quality of life among individuals and communities in lasting ways (Fredrickson, 2001; Keyes, 2002; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Additionally, positive psychology research clarified that mental illness and mental health are related, but distinct constructs, providing empirical evidence that mental health is more than the absence of mental illness (Keyes, 2002; Keyes, 2005), and introducing the concept of positive mental health. Early (mental) health promotion and population health research also supported the multi-level capacity and beneficial outcomes of promoting positive mental health. Findings demonstrated improved utility and health benefits of strengths-based programs focusing on positive psychosocial factors (i.e., empowerment, competence, resilience, active participation), in comparison to risk-reduction programs (Barry, 2001; Barry, 2007).

1.1.4 Solidifying mental health promotion as a distinct field of study

By 2005, the World Health Organization released their first report featuring mental health promotion, including a new definition of mental health as a state which encompasses positive functioning. The new definition cemented both the re-conceptualization of mental health and the essential place for mental health promotion in promoting population health. Around the same time, more and more research emerged, contributing to a growing body of literature studying theoretical and conceptual bases mental health promotion and demonstrating its utility and efficacy in improving health and preventing ill-health across a variety of settings (Barry, 2007; Barry, 2009; Jané-Llopis et al., 2005). The enhanced understanding of mental health and evidence of its utility across diverse populations and settings, emphasized the importance and efficacy of promoting positive mental health within the general population, as opposed to focusing only on individuals at-risk or diagnosed with mental illness. Although the disorder-focused model provides an important and necessary framework for treatment and prevention for individuals struggling with mental illness and for practitioners in relevant fields (e.g., clinical psychology, psychiatry), the shift towards a widely applicable and holistic view refined our understanding of mental health and unlocked its powerful ability to enhance overall health and prevent ill-health globally (Sharma et al., 2017). With this updated view taken in stride, contributions from positive psychology and mental health promotion pioneers have continued to inform an evolving framework for mental health promotion. Their research continues to explore MHP’s distinctiveness (as its own field), but inherent relevance to health promotion generally, its utility across multiple settings and scales, and its unique strengths-based capacity to simultaneously improve health and protect against poor health.

1.2 APPLYING PRINCIPLES OF HEALTH PROMOTION TO MENTAL HEALTH

1.2.1 Introduction

The meanings of health and well-being have evolved with time and vary across many contexts. There are various factors which can influence or contribute to both the absence/presence of disease, as well as good functioning. These are often referred to as types or sub-domains of health or well-being (i.e., physical, emotional, psychological, spiritual, social, and economic), all of which are important to overall quality of life (Government of Canada, 2019). The health promotion field operates within the public health domain and seeks to emphasize this holistic view of health by focusing on promoting well-being and supporting individuals facing illness at community, societal and governmental levels (World Health Organization, 2022). The scope of health promotion begins with improving healthy habits at the individual level, up to shaping health-related policy (World Health Organization, 2022). As effective health promotion results from the combined collaboration of individuals and institutions, everyone must take responsibility for their role in creating a healthy society (WHO, 1986). Rickwood (2011) found that mental health promotion has a goal to help individuals become their best selves, cope with stressors, and become active community participants at every life stage.

The World Health Organization (2005) provides the following definition of mental health: “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” (p. 2). Mental Health is part of the “holistic definition of health and therefore builds on the basic tenets of health promotion” (Barry, 2017, p. 5).

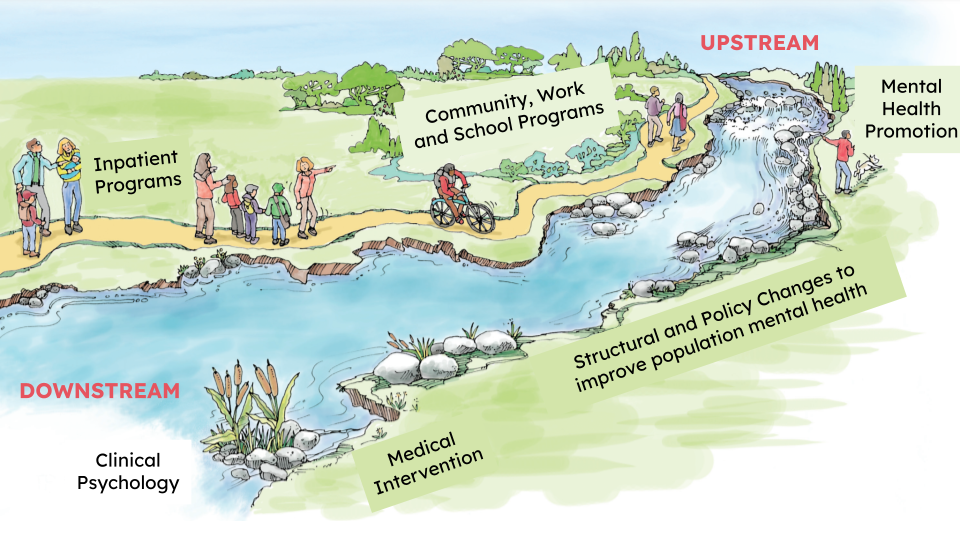

Since all types of health are interconnected, mental health promotion theories should focus more on goals to improve overall health (Jané-Llopis et al., 2005). This makes health promotion theories an even better fit to be used in mental health promotion, as they already have a focus on overall well-being (World Health Organization, 2022). Specifically, mental health promotion refers to developing effective ways for individuals and communities to have positive mental health (Windsor-Essex County Health Unit, 2019). Barry (2017) describes mental health promotion (MHP) as multi-leveled (individual, communal, and socio environmental). MHP follows an upstream approach, meaning it focuses on making structural changes to improve mental well-being of the entire population (Barry, 2017; National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2014). It is for everyone, as opposed to the downstream approach of clinical psychology, which as a primary focus on individuals with or at risk of mental illness (Barry, 2017; Gaspar de Matos et al., 2019; National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2014; see figure 1 for comparison; source). The upstream and downstream approaches can be compared with an analogy by Irving Zola:

“A witness sees a man caught in a river current. The witness saves the man, only to be drawn to the rescue of more drowning people. After many have been rescued, the witness walks upstream to investigate why so many people have fallen into the river. The story illustrates the tension between public health’s protection mandates to respond to emergencies (help people caught in the current), and its prevention and promotion mandates (stop people from falling into the river)” (National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2014, p. 2).

Here, clinical psychology (the downstream approach), can be compared to rescuing the individuals in the river- when an individual faces mental illness, clinical treatments aim to solve their mental health problems (National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2014). In contrast, MHP (the upstream approach) consists of proactive measures that aim to prevent individuals from falling into the river in the first place (National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2014). It responds to the determinants that contribute to an individual’s mental health, to inspire individuals to engage in a mentally healthy lifestyle (Barry, 2017).

Figure 1: A visual comparison of upstream and downstream approaches to mental health-promotion (National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2014).

Adapted from: National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. (2014). Let’s Talk: Moving upstream. Antigonish, NS: National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, St. Francis Xavier University.

This section describes the how various approaches in health promotion (The Ottawa Charter, The Socio-ecological Model, and Strengths-Focused Approaches) can be applied in MHP practice.

1.2.2 MHP in Programming and Policy

MHP programs vary in scope and context; however, true to the holistic and positive view of mental health, all programs focus on enhancing mental health and well-being, rather than the prevention or treatment of mental health challenges (Barry, 2009; Hill et al., 2023). Given this holistic mental health approach, programs less often target a specific mental health risk or disorder treatment populations. Although some focus on broad demographics, programs typically strive for inclusivity and are often embedded in diverse community contexts (Hill et al., 2023). MHP programs have been deemed an effective public health approach because evidence has demonstrated their effectiveness in improving population well-being. For instance, Barry et al. (2013) reviewed 22 mental health programs in populations of children and teens living in low and middle-class countries. Results showed most of the interventions that were implemented in a school setting positively impacted children’s emotional health and ability to cope with stressors (Barry et al., 2013). Similarly, community interventions for teens positively influenced their psychological and social health (Barry et al., 2013). Adult programming findings have also been promising. Le et al., (2021) found that across 33 adult MHP programs, the majority were effective, producing benefits that justified the program costs. Primary benefits included reducing the risk of depression, suicide, substance use, psychosis, anxiety, and eating disorders (Le et al., 2021). Preventative workplace models were one type of program found to be effective (Le et al., 2021). It is important to consider the benefits compared to the program cost because public health and mental health organizations have budgets they must adhere to, therefore more funds should be allocated to programs that are more successful in improving population mental health (Le et al., 2021). Cost-benefit analyses maximize the efficiency of both programs and their budgets (Le et al., 2021).

Many social factors, or determinants, interconnectedly influence mental health and general well-being (Compton & Shim, 2015). Policy creates and influences the social, economic, and political infrastructure which shapes these determinants and, thus, has the potential to impact mental health (Compton & Shim, 2015). Compared to implementation and evaluation of MHP programming, policy efforts relating to mental health status are less frequently evaluated. Growing recognition around mental health promotion, has resulted in the publication of various reports and initiatives (i.e., WHO, 2005; WHO, 2022). Additionally, certain countries have implemented policies and mandates which focus on the promotion of mental health, especially through positive enhancement lens. For example, New Zealand’s first “Well-Being Budget” recently committed to changing the way they prioritize and measure well-being, including looking beyond GDP as a sole measure of well-being and prioritizing the improvement of mental health and other related social determinants (i.e., poverty, Indigenous inequalities; Mintrom, 2019). However, there a need for research empirically evaluating effectiveness and utility of specific policies and initiatives across health, education, political, and economic sectors in both reducing mental health burdens, but enhancing mental health and overall well-being (Enns et al., 2016).

1.2.3 Using the Ottawa Charter to Inform Mental Health Promotion

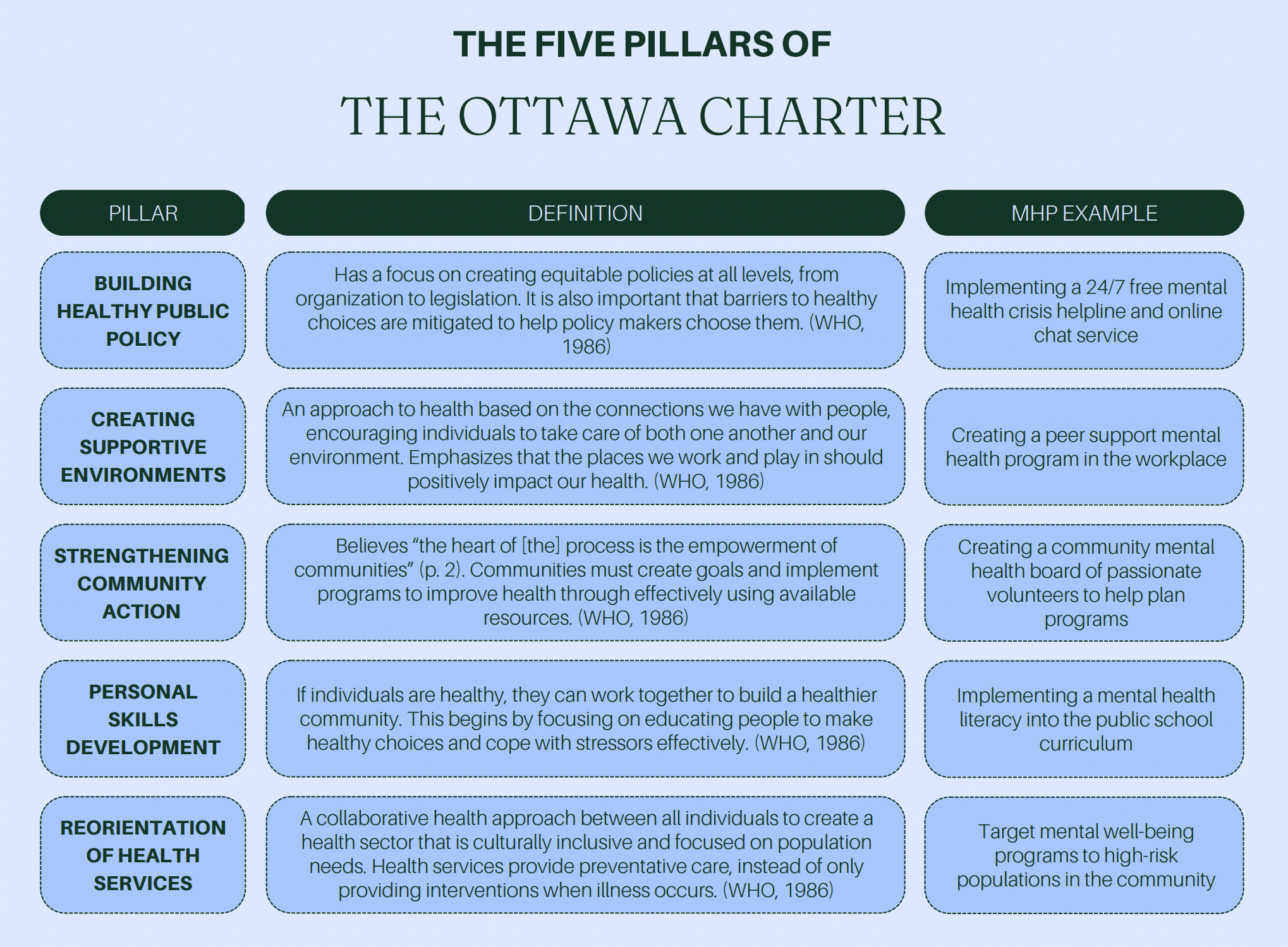

One key framework used in the field of health promotion is the Ottawa Charter, a well-known set of guidelines that shape many programs seen today (WHO, 1986). The Ottawa Charter was created 37 years ago, at the first health promotion conference, when the world knew they needed a new positively oriented public health strategy (Jackson, 2016). The Ottawa Charter can be used effectively for MHP because it focuses not only on the individual but also on the well-being of society (Rickwood, 2011). The five pillars of the Ottawa Charter contribute to understanding how a well-known approach to health promotion can be applied in mental health settings; they are summarized in Figure 2 below: (Jané-Llopis et. al, 2005).

Figure 2: The five pillars of The Ottawa Charter (WHO, 1986), and how they can be applied in mental health promotion settings.

*MHP = mental health promotion, template by (Amabile, n.d.-a)

Chapter 4 (The Social and Structural Determinants of Mental Health) reminds us that mental health is shaped by numerous factors (e.g., social support, spirituality, coping skills, workplace, and economic status) known as the determinants of mental health. The Ottawa Charter can be used as a program framework, to enhance the positive determinants of mental health, and eliminate the negative determinants of mental health (Jane-Llopis, 2007). For instance, the Youth Mental Organization in Australia is called Headspace and has found an effective basis on the five pillars of the Ottawa Charter, focusing on communicating, promoting, and preventing mental health disorders. It plays a large role in modifying the healthcare services available to youth and has helped them grow up in improved mental health settings (Rickwood, 2011). Some health promotion programs that have a basis in the Ottawa Charter have been shown to improve mental health even if that was not their primary goal, showing MHP programs can be effectively guided by the Ottawa Charter (Jane-Llopis et al., 2005).

We can see that MHP program results can motivate a larger change in the community (Herrman et al., 2007). Jané-Llopis et. al (2005) comment on the examples that build healthy health promotion programs and policies, to help community members learn and grow to their full potential. This includes improving the ability to provide nutritious foods and quality education to all people, regardless of socioeconomic status (Jané-Llopis et. al, 2005). Individuals need an environment that allows and encourages them to improve their determinants of mental health (Jané-Llopis et. al, 2005). This could include having a mental health professional periodically visit the homes of families at risk or with mental health disorders to assist (Jané-Llopis et. al, 2005). When locations at the organizational level (schools and workplaces) work together with families and friends at the interpersonal level, there is an opportunity for an additive effect to promote mental health (Jané-Llopis et. al, 2005).

The Ottawa Charter can be used as an assessment tool to determine the strengths and future directions of both MHP programs and the field as a whole (Rickwood, 2011). Rickwood (2011) notes the Ottawa Charter has helped develop stronger community involvement at the micro and macro levels. Micro level programs (such as Headspace mentioned above), empower community members and caregivers to participate in improving the mental health of the people around them (Rickwood, 2011). Macro level programs target larger scale policy measures (Rickwood, 2011). For instance, the GetUp! program focused on holding political leaders responsible to act on important causes (Rickwood, 2011). This has stimulated community growth in other locations like Ireland and has created changes in funding to help youth gain increased access to therapy. Overall, the Ottawa Charter provides well-thought-out guidelines that have been effective across multiple mental health settings.

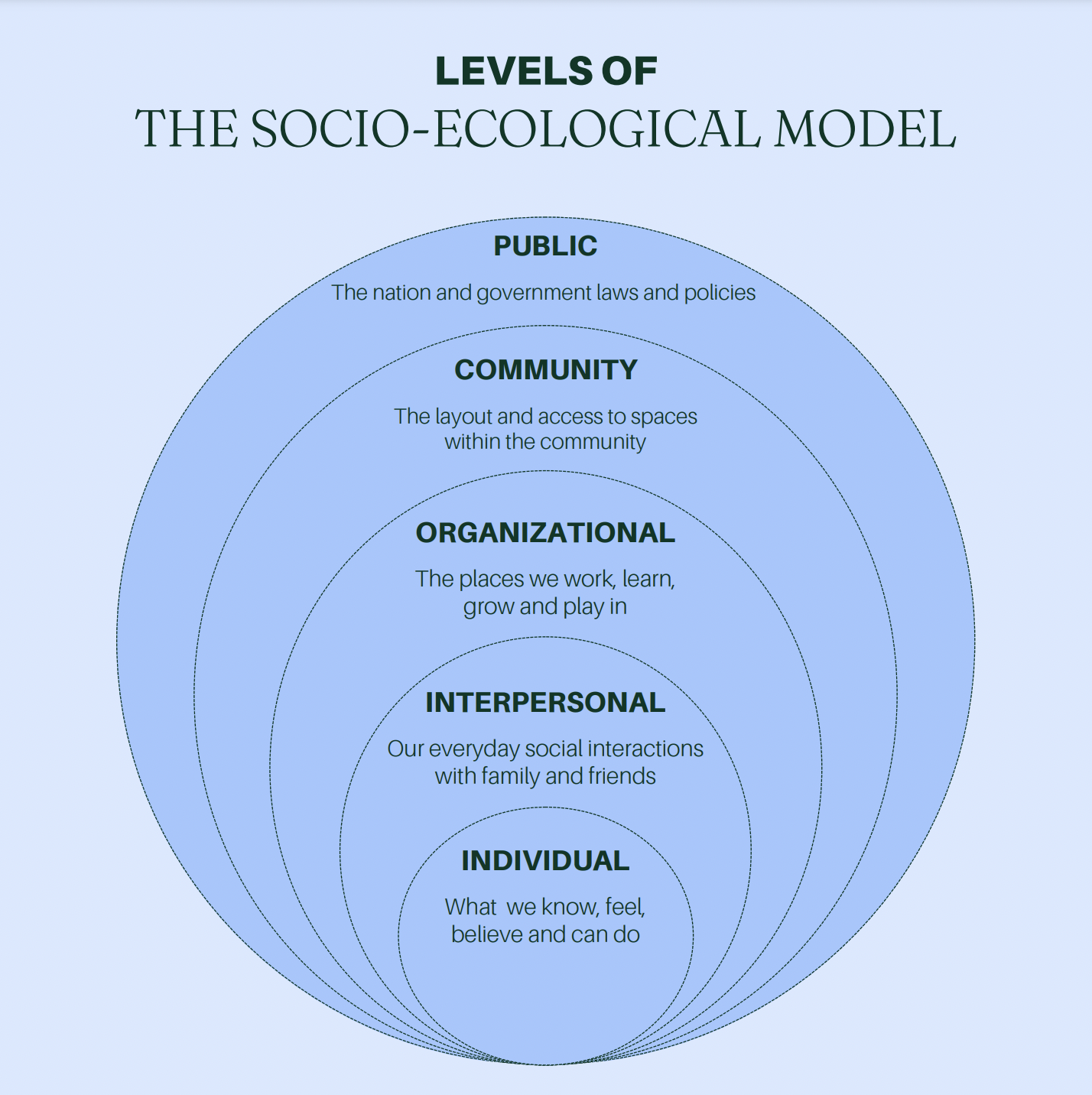

1.2.4 Applying the Socio-Ecological Model to Mental Health Promotion

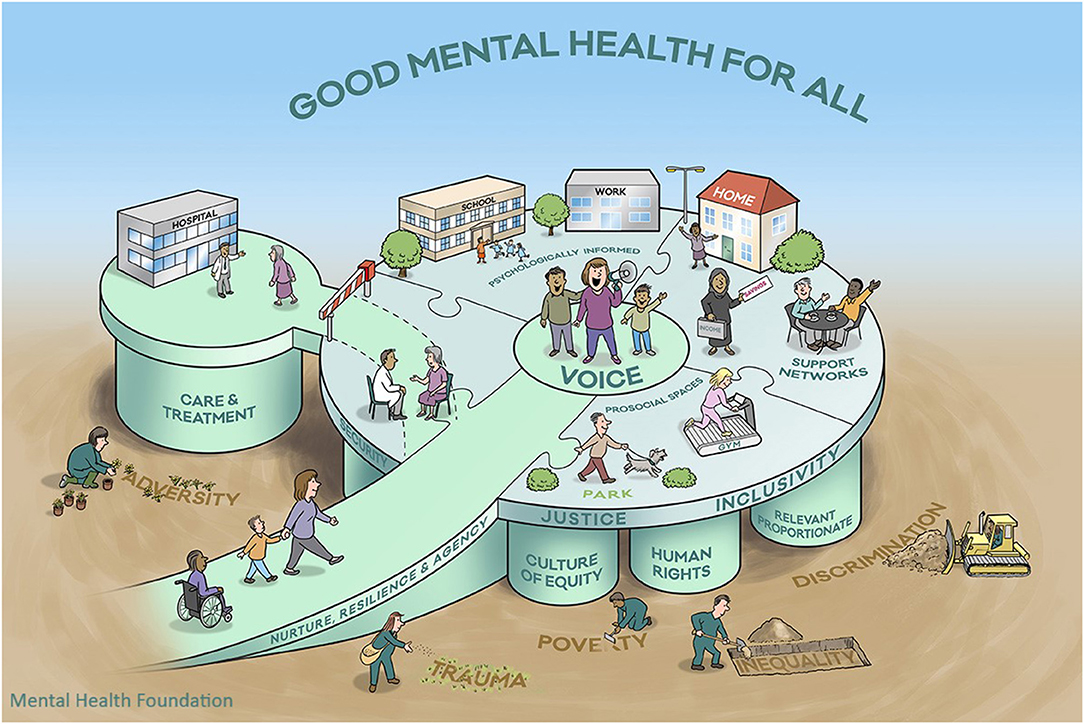

Another framework used in health promotion is the Socio-Ecological model. The Socio-Ecological approach shows that MHP operates at all levels- individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public (shown in Figure 3 below; Barry, 2007). Barry (2007) emphasizes the connection between an individual and their environment, and how that needs to be part of how we develop MHP theories. We need interventions that target more than one level of the Socio-Ecological hierarchy. The Socio-Ecological model can be applied to MHP because it demonstrates interconnection from the individual to the public level (Barry, 2007). For example, Kousoulis and Goldie (2021) adapted this model and created a visual illustration of how it is applicable to community mental health (Figure 4). Kousoulis and Goldie (2021) show that resilience and agency at the individual level are needed to sustain positive mental health at the community level. Individuals at the bottom of the diagram have barriers to positive mental health that get in the way of making a positive contribution to the interpersonal, organizational, community, and public levels (Kousoulis & Goldie, 2021). This reminds us that a community must be built on public pillars of equity, human rights, and respect, so all members can be active participants in positive public mental health (Kousoulis & Goldie, 2021).

Figure 3: The levels of the Socio-Ecological Model (Heise, 1999)

Template by (Aida, n.d.)

Figure 4: A Visual illustration of the Socio-Ecological Model adapted to fit the Scope of Mental Health (Kousoulis & Goldie, 2021)

1.2.5 Using Strength-Focused Models to Enhance MHP in Practice

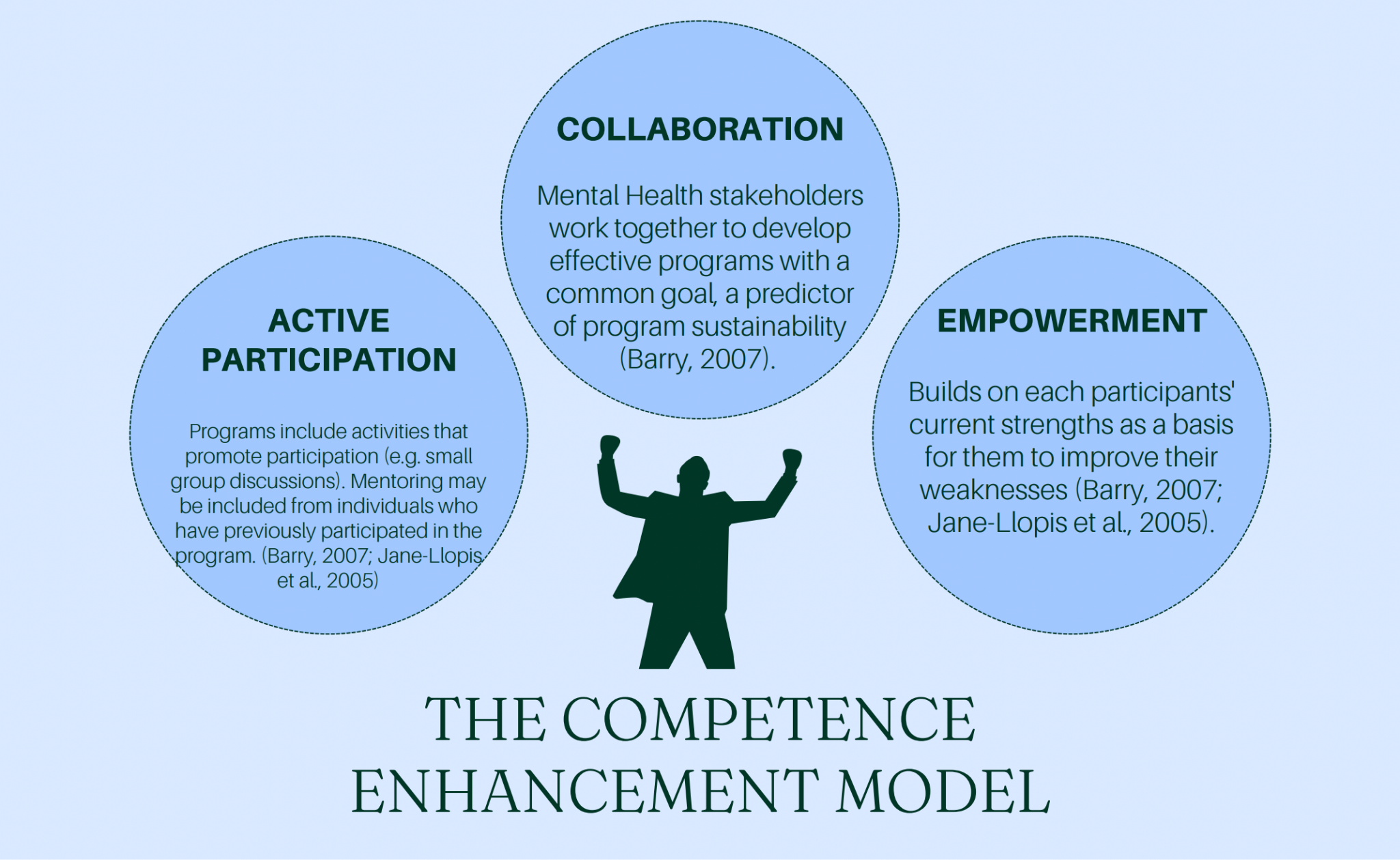

Strengths-based models of MHP (i.e., competence enhancement model) emphasize the importance of the determinants of mental health, as they are the components these programs try to improve (e.g. resilience, physical activity, and parenting styles; see Chapter 4: The Social and Structural Determinants of Mental Health) (Barry, 2007). An important aspect of this model is that it focuses on promoting positive mental health, while others simply aim to reduce mental illness or treating it when it occurs (i.e., risk-reduction, pathogenic approaches; Barry, 2007). These programs see mental health as a resource which helps individuals thrive and thus, focus on helping participants be confident and capable in coping with everyday life stressors by building positive mental health enhancing factors (Barry, 2007). For example, the competence-enhancement model focuses on integrating empowerment, participation, and collaboration to promote mental health (Figure 5) (Barry, 2007; Jane-Llopis et al., 2005). The skills and factors featured in specific strengths-based models have considerable overlap with skills needed for positive mental health, demonstrating the central importance of positive mental health to effective mental health promotion (Barry, 2007; Barry, 2009).

Have you ever joined a program and left feeling bored, disconnected, or worse about yourself? After a negative experience, most people will not return to the program. Additionally, policies which focus solely on the prevention of treatment of mental disorders only address certain populations (i.e., at-risk, or already mentally) after issues have already manifested (i.e., risk or diagnosed mental illness). By contrast, following a strengths-based approach means that policies and programs take an upstream approach which simultaneously prevents mental illness and enhances both positive mental health and general well-being in a more inclusive, efficient, and beneficial way (Barry, 2007; Barry, 2009).

The strengths-based model can be applied to MHP practice among both youth and adults, by building policies and programs which foster factors empirically supported in enhancing mental health and related competencies. The Community Mothers program provides home visits to first-time low-income mothers, educating and empowering them with the skills needed to be an effective parent (Barry, 2007). The strengths-focus impacts the design of this program by empowering parents by “drawing out the potential of parents rather than giving advice and direction” (Johnson et al., 2000, p. 337). Using an approach that empowers and works directly with participants allows needs and areas of growth to be identified so resources can be used efficiently and the program can succeed (Barry, 2007, Jane-Llopis et al., 2005). Strengths-based models have also been proven to be effective in programs for teens and youth (Barry, 2007). The Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) program set a goal to help children understand the emotional expression and regulation, self-control, and problem-solving (Greenberg et al., 1995). This uses positive elements characteristic of the strengths-based approach, including participation (questions throughout the lesson) and collaboration (role-play of skills) based activities (Paths Program LLC, 2021). When PATHS was used in 30 second and third-grade classrooms, results showed children could communicate and manage their emotional experiences better (Greenberg et al., 1995).

Figure 5: The three components of the competence enhancement model (Barry, 2007)

Template by (Amabile, n.d.-b)

1.2.6 Conclusion

This portion of chapter 1 provides on overview of public health contributions to health promotion and supports the application of a health promotion approach in improving and promoting mental health. The Ottawa Charter informs MHP efforts by identifying five pillars on which to act (healthy public policy, supportive environments, community action, personal skills, and health services; WHO, 1986). This has been proven effective in many mental health programs, including Headspace (an Australian youth program). Like the pillars in the Ottawa Charter, the Socio-Ecological Model prioritizes health at every level, from the individual to public policy (Barry, 2007). The Socio-Ecological Model intends to create a society where individuals improve the health of communities, and communities improve the health of individuals in return (Barry, 2007). Across all these levels, employing a strengths-focused approach greatly enhances the efficacy and success of mental health promotion in practice. For example, looking at the community level of the Socio-Ecological approach, the competence enhancement approach guides programs to be empowering, interactive, and collaborative (Barry, 2007; Jane-Llopis et al., 2005). When these various models are tailored and used effectively within relevant populations, public mental health and general well0ebing can be improved.

1.3 SYSTEMATIC CONCEPT ANALYSIS OF MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION

Clarifying the concept of mental health promotion and pinpointing contributing factors are imperative to overcoming existing barriers, guiding future research and study in this field, and maximizing the current utility of mental health promotion among individuals, communities, and across countries.

1.3.1 Introduction

The emerging field of mental health promotion has built on many theoretical and conceptual frameworks from the domains of health promotion, public health, and positive/community psychology. Definitions, research, and practice of mental health promotion also vary across contexts, cultures, political landscapes, and over time (Kovess-Mastefy et al., 2005; Tamminen et al., 2016). We’ve discussed many of the current models and perspectives informing current understanding of mental health promotion, including the competence-enhancement approach and socio-ecological model. These perspectives all make important contributions to the field, however, differences between them have challenged our ability to develop a one-size-fits-all conceptualization of mental health and mental health promotion. Thankfully, our understanding of mental health is largely widely accepted. However, there remains division and uncertainty regarding other aspects of mental health promotion. For example, some argue that mental health promotion encompasses both the prevention and promotion of mental health, while others see prevention of mental disorders as a distinct, separate goal outside the direct scope of mental health promotion.

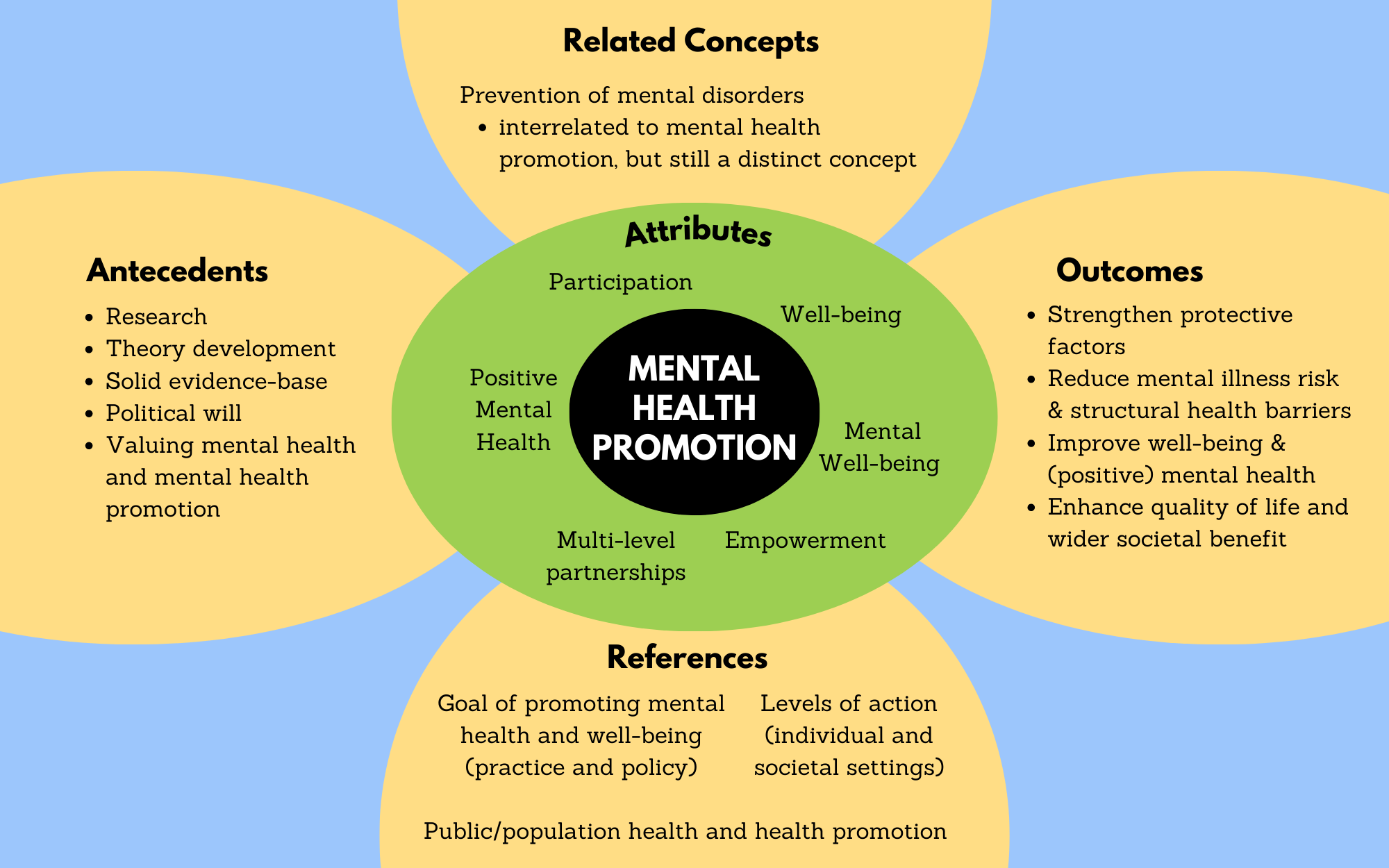

As MHP and programming grows in popularity, it becomes harder to manage existing inconsistencies in the definitions, aims, and components which translate into practice (i.e., prevention and treatment). Fortunately, Tamminen et al., (2016) conducted a systematic concept analysis, which involved reviewing the existing literature on MHP and using a structured framework to identify the most consistently agreed upon attributes, antecedents and consequences, related concepts, and reference terms (Figure 6). These identifications greatly advance and organize knowledge on MHP and provide the clarification necessary to streamline its scope of relevance and practice. The map of their work depicted below provides a great educational tool outlining the concept of mental health promotion.

Figure 6: Visualization of a concept mapping of mental health promotion based on a concept analysis and figure map completed by Tamminen and colleagues (2016).

1.3.2 Mental Health Promotion: What, Why and How?

The attributes of mental health promotion describe the concepts’ unique characteristics and qualities, in other words, the “what” of MHP. Based on attributes, mental health promotion can be understood to promote positive mental health to achieve well-being through empowerment, participation, and multi-sectoral partnerships. Positive mental health includes self-esteem, optimism, subjective well-being, and stress/adversity coping skills and in addition to mental well-being, was recognized in existing MHP research mostly at the individual-level (Tamminen et al., 2016). Both these attributes were recognized as important to MHP, but not central in current policy or strategy literature. Alternatively, the attributes of partnerships and cross-sectoral integration/efforts were dominant in the extant policy and strategy articles (Tamminen et al., 2016). Both empowerment and participation were identified as key features of mental health promotion, most specifically, in relation to how to foster mental health promotion in practice. For example, empowerment is an aim of the Ottawa Charter and both empowerment and participation are key aims considered in building and evaluating MHP programs (Barry, 2007; WHO, 1986).

The references clarify the domains and circumstances which mental health promotion is most relevant while antecedents identify what is required or what comes before MHP. Tamminen and colleagues (2016) review of MHP references illustrates that mental health promotion aims to improve mental health and well-being across multiple socio-ecological levels through policy, strategy/research, and practice (aka programming). Further, these goals and actions are situated within the scope of overall health promotion, specifically in relation to public and population health domains (Barry, 2007). While references provide context for the identified attributes, there are also certain factors (i.e., antecedents) which help ensure MHP has the attention and resources to thrive. These include political will, strong research theory and evidence-base, and people who value mental health and mental health promotion (Tamminen et al., 2016). The antecedents help identify important emphasis points for what can be done across multiple levels to advance the promotion of mental health either through direct actions from individuals, communities, or institutions/government or further research. Together, the references and antecedents help to identify the “how” of mental health promotion, which explains the relevant context and concrete factors leading/contributing to MHP.

The identified consequences tie everything together. As the “why” of MHP, the outcomes which occur from MHP rationalize why it is so important and widely beneficial. Findings demonstrate that MHP improves well-being, strengthens many protective factors and reduces risk factors for mental disorders, and also permits a wide range of broader societal benefits (e.g., social and economic capital, societal productivity; Moodie & Jenkins, 2005). Thus, the consequences of MHP can extend beyond the initial points of focus (i.e., mental health) and goals (i.e., enhancing well-being; Tamminen et al., 2016). For example, the ability for positive mental health promotion efforts to be effective in primary intervention/prevention of mental illness, in addition to enhancing well-being. These extended benefits emphasize the broad utility and efficacy of MHP and suggest that investing in MHP is a worthwhile endeavour, in the interest of individual and community mental health, public health, and general societal functioning.

1.3.3 Barriers to MHP in Understanding and Practice

Despite the value gained from synthesizing and reviewing current knowledge on MHP, many barriers continue to limit MHP research and practice and challenge consistent conceptualization of mental health promotion. Some of these barriers include a lack of research (especially recent research and programming/policy evaluation research specifically), cross-cultural inequalities (lack of programming/policy and evaluation in developing countries), and a persistent lack of a clear definition of MH(P) (e.g., understanding mental health separate from mental illness, confusing well-being, and mental health, Barry, 2007; Moodie & Jenkins, 2005; Tamminen et al., 2016). Therefore, future research and practice must also address gaps in our understanding of MHP itself and build a more solid evidence basis for its effectiveness, as filling these knowledge gaps will improve the efficacy of MHP in research practice and provide stronger rationale for public health action to promote mental health promotion. Addressing these barriers might include integrating a more concrete and widely accepted theoretical and conceptual definition of mental health promotion that can be adapted for use across various contexts, funding more policy and program implementation, evaluation, feasibility research to build a stronger evidence base for building the most effective MHP programs and policy, etc.

1.3.4 The Value of Concept Analysis: Moving forward with MHP

Clarifying MHP as a concept is essential in optimizing study and practice of MHP. Examining the findings from Tamminen’s concept analysis help to elucidate how and in what circumstances each component of MHP distinctly contributes to mental health promotion efforts. They also identify precursor factors which can be enhanced to ensure MHP can flourish and outline the outcomes that occur when it does. The vital information gained from synthesizing the literature to conceptualize MHP is useful in multi-faceted ways. It can act as an educational tool which enhances public/political understanding and appreciation for of the meaning and benefits of MHP or even a conceptual/theoretical guide for future MHP practitioners and researchers. Evaluating the current concept of MHP can also reveal strengths and weaknesses and help to guide concrete solutions based on these evaluations. For example, mapping the consequences not only rationalizes the importance of MHP to relevant populations (i.e., policy makers, government funding evaluators, the public, etc.), but it also may provide a list of outcomes useful for both targeting certain outcomes with tailored MHP initiatives and/or evaluating the success of MHP efforts following implementation. Additionally, the widespread socio-ecological levels and importance of cross-sectoral partnerships to MHP suggest that MHP must be addressed as an issue of public health and employ cross-sectoral approaches to ensure MHP efforts are effectively carried out across all relevant socio-ecological domains (Tamminen et al., 2016).

1.4 FLOURISHING AS A GOAL FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION

1.4.1 Mental Well-Being vs Mental Health

As you may have noticed throughout the chapter, well-being and mental health are often discussed together and sometimes used interchangeably. Indeed, well-being has been identified as both an attribute and outcome of mental health promotion. However, well-being and mental health are separate but related constructs (Cloninger, 2006). Well-being refers to an overall sense of how life is going which is subject to daily fluctuations (Waterman, 2007), and mental health reflects a spectrum of functioning that shapes one’s ability to handle stress, make decisions, and cope with the ups and downs of daily life (Orpana et al., 2016). Mental health and well-being may bidirectionally influence one another; maintaining positive mental health may lead to a sense of well-being (such as being satisfied with one’s life), and vice versa, enjoying a sense of well-being may be a protective factor against poor mental health. As mental health is a necessary component of overall well-being, there is a need for effective population interventions across the globe (Barry, 2007).

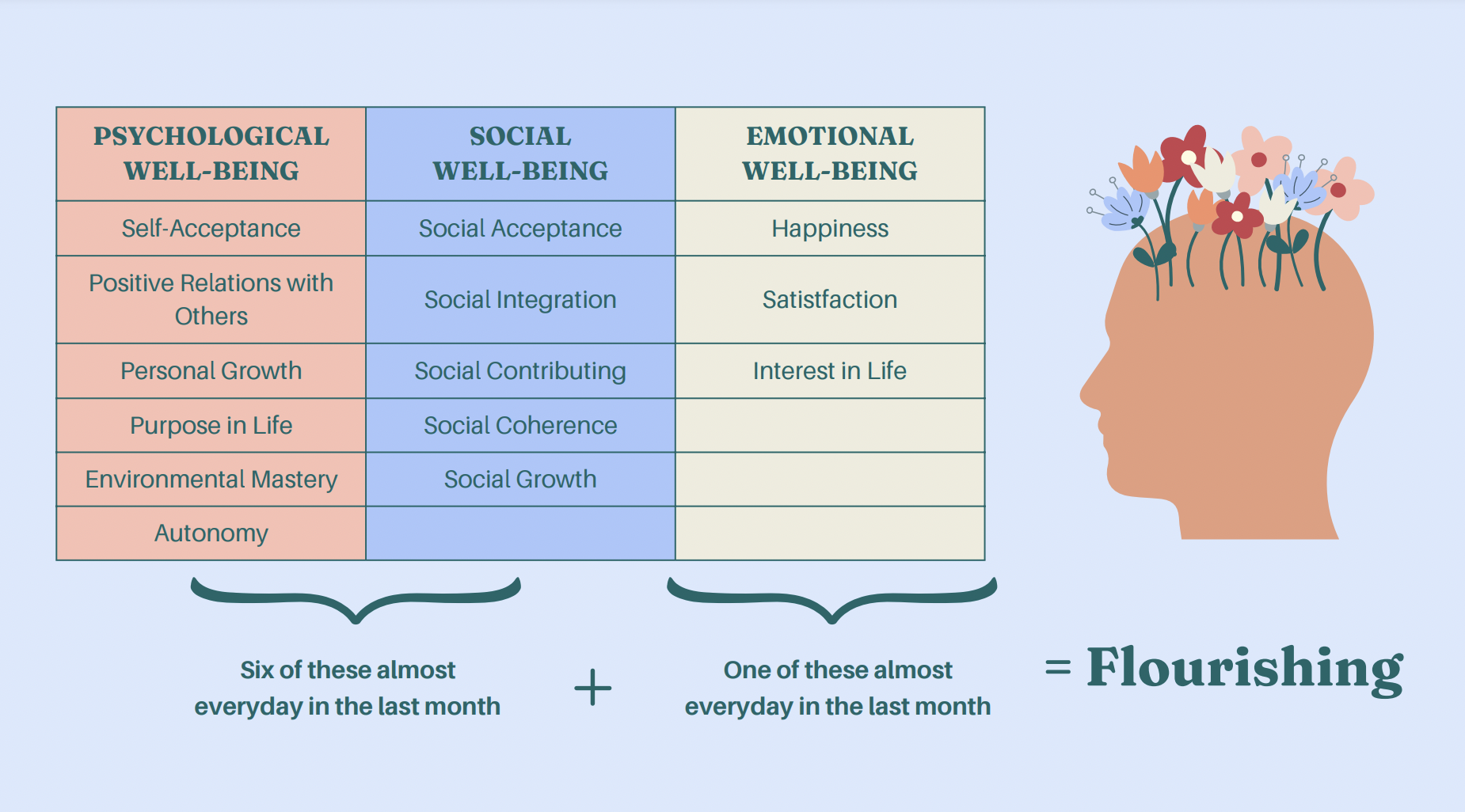

1.4.2 Positive Mental Health as Flourishing

Positive mental health is a true state of well-being rather than just the lack of mental illness (Barry, 2009, pg. 4). Possessing and maintaining positive mental health is known as flourishing (Keyes, 2002). In other words, flourishing can be thought of as a state of complete mental health, shown through consistently high levels of well-being across three key domains (i.e., psychosocial, social and emotional well-being; see Figure 7; Keyes, 2002; Keyes, 2014). Keyes (2014) argues “anything less than flourishing creates problems for society, it’s not just depression and mental illness” (14:42-14:50). Indeed, his research clarified that although positive mental health is related to mental illness, the two concepts are distinct from one another (Keyes, 2002; Keyes, 2005). These findings illustrate that mental illness is not a limiting factor that keeps one from flourishing, and that all individuals are capable of it (Keyes, 2014). This is an important perspective we carry throughout the rest of this textbook, and that generates strong support for positive mental health as an important goal for MHP.

1.4.3 Flourishing and MHP

Promoting flourishing is a route to well-being that is possible for all populations and has the potential to be extremely beneficial, not only to mental health, but to broader levels of both societal and individual functioning in everyday life (VanderWeele, 2017; Hone et al., 2014). When people are flourishing, they miss less work and face fewer physical limitations (REF). Additionally, having positive mental health is linked with many positive outcomes including problem-solving, productivity, and stress management (Jané-Llopis et al., 2005). These findings support that flourishing may act as a central indicator of human functioning, with determinants and outcomes which include and extend beyond physical and mental health (i.e., financial stability, sense of purpose; VanderWeele, 2017). Positive mental health or flourishing has, therefore, become an attractive concept within the domain of public health and (mental) health promotion. Even early advances in health promotion identified the importance of striving for positive health in an inclusive way. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO; 1986) emphasizes that good health promotion approaches focus on advocating for positive health, choosing programs that equally enable everyone to maximize their potential, and mediate the effects by getting the government and other stakeholders involved. Since then, positive mental health has been identified as both a key attribute and important outcome/aim of mental health promotion (Tamminen et al., 2016). Promoting positive mental health is widely recognized as central to successful mental health promotion efforts (Barry, 2001; Barry, 2009; Keyes, 2007; Kobau et al., 2011).

Figure 7: The criteria for an individual to fit the definition of flourishing based on the characteristics that make up the 3 types of well-being- Psychological, Social and Emotional (Keyes, 2014).

1.4.4 Overcoming barriers using an integrated approach

Despite the recognized importance of flourishing to mental health promotion, there remains many barriers to its study, practice, and implementation. While support for flourishing as a pathway to overall mental well-being is more extensive, research investigating implementation and evaluation of flourishing-aimed practice is limited (Keyes, 2010). This precludes clarity in identifying the most effective ways to implement and evaluate interventions and policies in promoting flourishing. These barriers will be discussed more in later chapters which focus on MHP programming across various settings, as well as MHP policy needs (i.e., Chapter 3). However, some existing barriers might also be addressed by integrating the largest existing bases of knowledge and practice relating to positive mental health and flourishing.

Although the term flourishing as positive mental health originates from positive psychology, positive mental health is a shared goal/concept within both positive psychology and public (mental) health promotion (Kobau et al., 2011). Additionally, the term flourishing in public health domains is used more loosely to extend beyond mental health and include optimal functioning across many social and personal domains (VanderWeele, 2017). Across both fields, positive mental health is viewed as the resource which permits social, emotional, and psychological functioning across multiple levels, but both fields also view, define, study, and aim to foster positive mental health in unique ways (Kobau et al., 2011). Positive psychology focuses on examining and identifying psychological assets (i.e., positive individual traits, emotions, relationships, and enabling institutions etc.) which permit individuals and communities to thrive and flourish (Kobau et al., 2011; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). In contrast, health promotion and public health efforts focus on building strong public policy, socio-ecological environments, personal skills, and health services to promote health (Kobau et al., 2011).

Given the many similarities and shared goals and concepts between these fields, there has been some opportunity for cooperative development, research and practice relating to flourishing in positive psychology, and positive mental health in the field of mental health promotion (Kobau et al., 2011; Keyes, 2010). However, the disconnect between these fields exacerbates existing limitations and barriers within each. For example, there are multiple different definitions and models of flourishing within positive psychology and limited research providing practical guidance for the implementation of interventions which promote flourishing (Hone et al., 2014; Keyes, 2010). Thus, conceptual differences in terminology and research gaps between fields contribute to lesser integration of flourishing research and practice into public health MHP efforts, which tend to focus on more social factors, than psychological (Kobau et al., 2011). The disconnect between fields therefore limits understanding of how both psychological and social components and factors come together to contribute to the promotion of positive mental health. However, many of the field-specific strengths and limitations complement one another, with strengths in positive psychology accounting for weaknesses in public health promotion and vice versa. The integration of more concepts, theory, and practice from positive psychology on flourishing and public health on positive mental health may advance and improve MHP efforts in building flourishing individuals, communities, and societies (Kobau et al., 2011; Tamminen et al., 2016).

1.4.5 Conclusion

This chapter summarizes the central concepts of this textbook and their origins, existing empirical evidence and theory supporting mental health promotion, and practical realities and implications for mental health promotion today. We’ve reviewed that mental health promotion is researched and practiced largely within a mental health promotion framework in the domain of public health, but also incorporates important influences from positive and community psychology. Mental health promotion has evolved with these fields, and with public understanding of mental health, to grow into a vital area of research and practice, with its own distinct features and outcomes. MHP informs how we can foster positive mental health across multiple socio-ecological levels and has benefits which extend to overall well-being and functioning of individuals, communities, and society at large. Integrating existing research and knowledge within the health promotion field, as well as beyond (i.e., positive psychology and flourishing) may guide future practice (i.e., policy and programming) and research adjustments needed to overcome barriers and advance the field.