6 THE ROLE OF COMMUNITY IN MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION

Laura Colford; Neve Clute; and Riley Wells

This chapter outlines characteristics of successful community mental health promotion that can be considered when planning, implementing, and evaluating programs to address the challenges of having a complex and ever-changing community setting.

6.1 KEY THEMES AND MAIN IDEAS

6.1.1 Introduction

Community MHP involves fortifying community resources and connections with the ultimate goal of fostering positive mental health. Communities unify diverse groups of individuals with unique strengths, across a wide variety of settings. In many community settings, there is room for opportunity and growth to happen among community members at both the individual and group levels. For example, community interventions can encourage community members to engage in positive MHP within their local settings, like community centres (Barry, 2005). Utilizing communities as a setting for mental health promotion (MHP) shows great promise and this has been recognized by many global public health agendas for health promotion (Jané-Llopis & Barry, 2005; Herman & Jané-LIopis, 2005). Evidence shows that highly structured and specific MHP programs delivered in community settings extend beyond basic healthcare services to have distinct positive impacts on community mental health (Jones et al., 2013). However, communities can be challenging settings to promote mental health because they are complex and ever-changing (Barry, 2007). Additionally, the several sub-settings such as schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods and diverse populations of people comprising communities, blur the lines between socio-ecological domains and demographics. To continue developing and enhancing community MHP, we must consider relevant factors and analyze existing gaps and limitations that occur at each stage of MHP programming and use that learning to inform future research directions and needed action.

6.1.2 The Structure of Community Mental Health Promotion

Positive Mental Health & Inclusivity from Positive & Community Psychology

Positive mental health is not achieved only through individual or societal level supports, but also through the development of community assets (Kobau et al., 2011). The promotion of positive mental health within the community is at the heart of community mental health promotion. Positive psychology contributes to the conceptualization of positive mental health within community MHP (Kobau et al., 2011). This emphasizes strengths-based approaches which acknowledge that truly fostering mental health involves the enhancement of people’s social, emotional, and psychological functioning, rather focusing only on mental illness (Keyes, 2002). Community mental health adds that these efforts (i.e., programs and policy) should be tailored to address and respond to unique mental health needs of each distinct community and should be inclusive to as many community members as possible (Caplan, 2013; Hill et al.,”in press”). Additionally, both fields also provide empirical evidence for the many factors which can simultaneously enhance individual and collective well-being of community members to both improve their mental health and foster wider social and health benefits (Kobau et al., 2011; Tamminen et al., 2016; Jané-LIopis et al., 2005).

Community Involvement from Community Development

The field of community development is also closely tied to community (mental) health promotion, as community-based approaches are surrounded by the theory that action creates change. Geographical closeness is often perceived as a primary requisite to community; however, some community development theorists suggest community can exist outside geographic boundaries and is instead characterized by shared identity and norms of a collective (Bhattacharyya, 2004). In accordance with this view, community development is defined as a process whereby the members of a given community work collectively to address challenges and achieve community goals (United Nations, 1995). True community development, therefore, involves community members, even if initiatives are directed by exterior institutions or individuals. Partnerships and relationships are at the focus of community MHP, where individuals, groups, health professionals and agencies collaborate to achieve desired common goals. Thus, community MHP and community development co-exist when community members are in some way involved in the mental health promoting efforts within their given community.

Community development also emphasizes many core principles and theories which are relevant to general and community-specific mental health promotion. Among many others, the notions of capacity building, active participation, empowerment, and social inclusion are all very essential considerations in community MHP (Arnstein, 1969; Raeburn et al., 2006; Bhattacharyya, 2004). Active participation emphasizes the importance of community consultation and involvement within community MHP initiatives. Additionally, when community members are involved and included in equitable and meaningful ways and partnerships and collaborations with relevant stakeholders are maximized, this fosters capacity building which inspires empowerment among community members and can act as a powerful force for achieving mental health promotion goals (Raeburn et al., 2006). It is also imperative that all members of the community are considered and included in non-tokenistic or coercive ways for true inclusion, to ensure there is just and equitable opportunity for community members to access and reap benefits towards their mental health (Arnstein, 1969; Raeburn et al., 2006). Thus, researching and addressing potential barriers to program participation and those which prevent some from retaining maximized program benefits are imperative when planning, implementing, and evaluating community programs aiming to promote mental health.

Practical Components of Community MHP Programming: The Three Stages

Community MHP is executed through programs and/or policies. The development and functioning of these programs and policies can be broken down into three stages. The planning stage involves the creation and preparation of MHP programming for use in the community. Securing proper education, community collaboration, and preliminary background are important in planning and developing effective programs. As we will discuss below, there are many tools useful in facilitating effective program planning. Among the most relevant are needs assessments (Barry, 2000).

The next stage, implementation, is where programs are put into practice within the communities (Barry, 2005). Careful consideration and accommodation in response to the factors influencing implementation in both the short- and long-term are essential to ensure the program can be properly executed and sustainably maintained. Barry (2007a) stresses the importance of researching MHP program implementation to ensure suitability with the community context and identify distinct implementation-factors which contribute to practical program effectiveness.

The final program evaluation stage ensures that MHP programs are successful in the communities where they are implemented. Evaluation should be performed at all stages of the program, including the program inputs, the program’s impact, and the program’s outcomes (Barry, 2003). By employing appropriate and structured monitoring and evaluation methods, the program outcomes, feasibility, and features integrated in both planning and implementation stages can be identified and examined to reveal relevant factors contributing to the program’s effectiveness and community fit (Barry, 2005; Nakkash et al., 2011). Evaluation is therefore key can be in informing future community programming and enhancing program sustainability (O’Connor-Fleming et al., 2006).

6.1.3 Considerations for Community Mental Health Promotion

Community Perspectives and Collaboration

Community MHP programs must be collaborative and include community perspectives to ensure that the program is effective and benefits the target population. Including community perspectives can help in planning and implementation, by building effective programs that are best suited to the distinct needs and preferences of the target community (Barry, 2003). Collaboration between community stakeholders can improve the quality of community MHP programs and reduce health inequities in community (Barry, 2007a; Thompson et al., 2016). By improving service coordination across many levels and settings within the community, collaborative programs establish a more effective and comprehensive platform for community MHP initiatives (Carmola & Bond, 2002). Getting people involved in local communities creates the most feasible and greatest impact when community members solve local issues. Incorporating practices from community development, such as community capacity building, support active participation, empowerment, and collaborative partnerships can be highly beneficial in promoting community mental health and integrating these efforts synergistically within larger-scale health promotion efforts (Raeburn et al., 2006). Including community stakeholders in equitable agreements for programs and research requires taking the time needed and adhering to appropriate procedures to create strong partnerships. With trust, respect, and two-way knowledge sharing, the expertise of community leaders and other stakeholders can be merged fairly with that of researchers and program organisers (Castillo et al., 2019). When this balance is achieved, the resulting programming best suits community needs in ways which are also feasible and evidence-based for researchers and program organizers (Barry, 2007a). This maximized utility could bring many benefits, for example, less program costs in both implementation and program evaluation due to support from community members and structured frameworks to guide each stage of programming. Incorporating community members involvement in both the planning and implementation stages may also help to foster active participation and empowerment within the community, attributes that on their own help to promote positive mental health (Barry, 2007b).

Addressing Sociocultural Needs and Inequalities

When developing community MHP programs, social disparities and distinct cultural factors can contribute to health inequalities and must be considered at all stages of MHP programming. Community MHP programs must be culturally relevant and appropriate and consider the determinants of mental health related to race, ethnicity, culture, religion and other social factors (Compton & Shim, 2015; Gopalkrishan, 2011; Castillo et al., 2019). For example, the consequences of colonization such as forced cultural suppression and assimilation have direct impacts on mental health of Indigenous peoples in Canada, thus community MHP programs targeting Indigenous communities must consider the health impacts of colonization and focus on knowledge sharing and empowerment (Kirmayer et al., 2003). Additionally, programs targeting diverse ethno-cultural groups must consider the health impacts of relevant factors, including systemic racism, cultural values, discrimination experienced, etc., to ensure they meet the complex needs of racially marginalized individuals (Gopalkrishan, 2011; Jung & Aguilar, 2015). Outside racial and ethnic groups, there are other individuals who are pre-disposed to adverse outcomes relating to social or material deprivation (i.e., incarceration, homelessness) which also require further consideration and attention in community MHP programming (Castillo et al., 2019).

6.1.4 Community Mental Health Promotion: Tools in Practice

Needs Assessments

Community needs assessment are a flexible method for determining priorities and resource allocations that will improve health and reduce inequities, while also examining the health challenges a community is facing (Ravaghi et al., 2023). They are key in planning and implementing a successful community MHP program (Barry, 2000). Needs assessments typically consist of a series of questions regarding the beliefs, opinions, and experiences of community members, however, they can be customized and adapted in many ways depending on which needs are being evaluated and which methods might best suit the population of interest (Barry, 2000; Ravaghi et al., 2023). For example, the relevant data can be collected qualitatively, quantitatively, or use a combination of the two. Two common forms of needs assessments are surveys and the vignette method (Barry, 2000). Surveys include collecting data from the target population using individually answered questions and responses collected online or in-person. The vignette method includes the provision of constructed situations or scenarios to the target population and collects information about their position in the situations depicted. These assessments use diverse and flexible means to identify perceived challenges, barriers, and perspectives on the issues that a program is looking to improve upon.

When needs assessments are used effectively and capture community perspectives, they reveal useful information and enhance community MHP in multi-faceted ways. Firstly, they provide structured guidance to program planning and implementation within a specific community. For example, Barry (2000) conducted a needs assessment prior to program implementation to examine the interpretation of mental health issues in a rural community life and found that men under 40 years old, and younger respondents were more apprehensive about accessing mental health care, and less concerned with depression and suicide rates. This information guided which groups to target with programming specific to their needs (Barry, 2000). Beyond informing MHP programming, Jorm (2012) supports the use of needs assessments in relation to mental health literacy, suggesting that they can be used to identify gaps within public knowledge on mental health which guide the enhancement of mental health literacy and reduction of stigma in the overall community. Additionally, the data collected from needs assessments can be shared with certain groups (i.e., mental health professionals, governments, health organizations) to inform them about community needs and guide or rationalize future programming efforts (Sacchetto et al., 2022). If needs-assessments surveys are re-distributed following the program, the differences can be compared in the evaluation stage to evaluate the program’s effectiveness and identify how community attitudes and needs have shifted from before to after program implementation.

The Logic Model

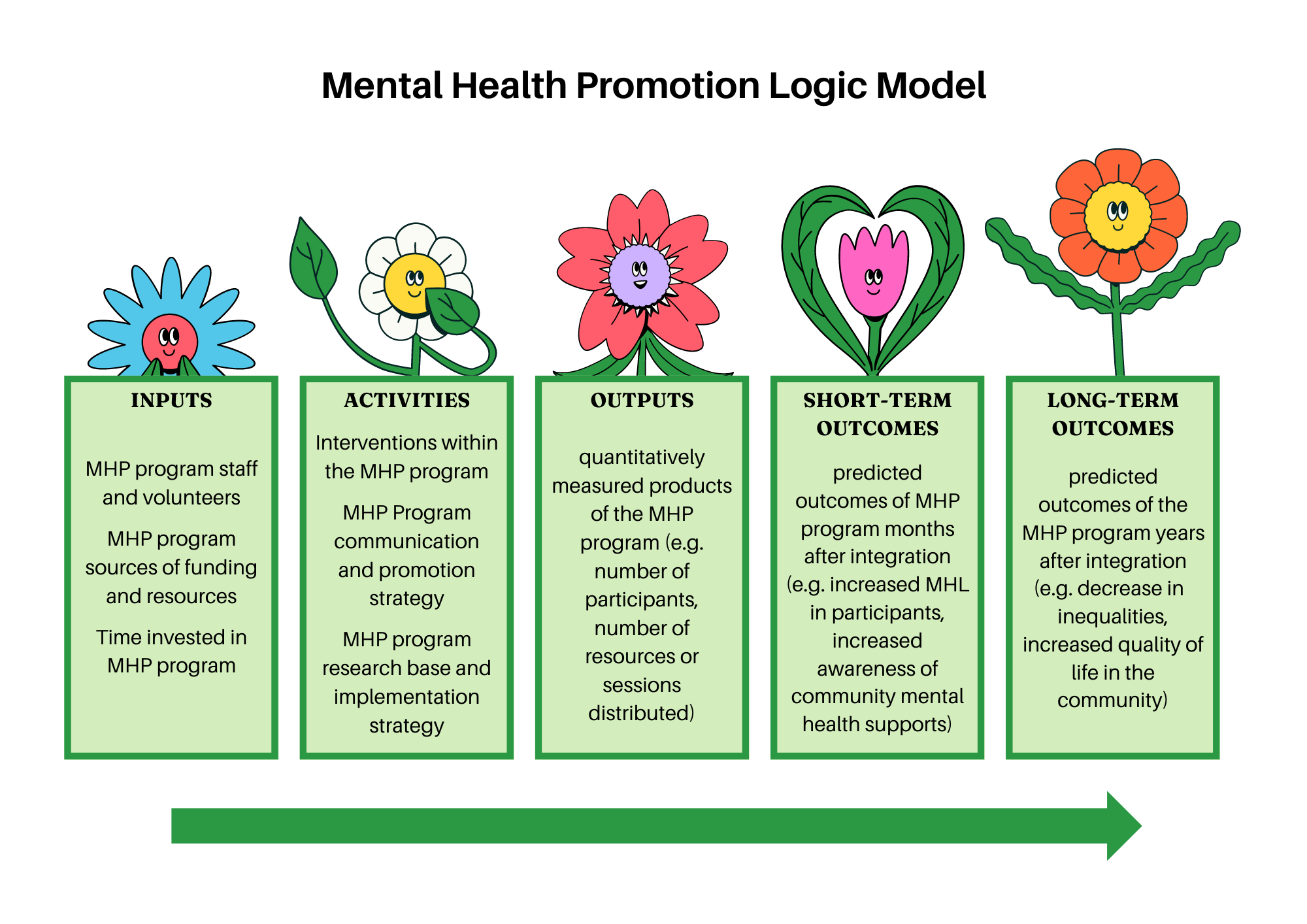

Use of the logic model framework is a beneficial strategy for evaluating programs. Simply put, a logic model aims to visually portray the connection between program operations and intended outcomes (Lando et al., 2006). While monitoring the implementation of programs and collaboration, logic models offer a helpful framework for exchanging perspectives and ideas (Barry, 2003). The logic model allows evaluation to occur at multiple steps of the implementation process, making it an ideal evaluation framework (Barry; 2007a). The logic model provides the evaluator with an outlet to analyse the program at every step of the process, including the program inputs, the program outputs, and the long-term and short-term outcomes of the program (Barry, 2003; Barry, 2007a). Using a logic model also gives program practitioners and evaluators the chance to collaborate and share knowledge and perspectives while creating the program design and sequential planning (Barry, 2003). A logic model can be very simplistic or can be more complex, depending on the scale of the program.

Figure 12: Example of a Logic Model for Mental Health Promotion Programs (Abdi & Mensah, 2016; Lando et al., 2006; Vonk et al., 2020).

Community mental health programs must accommodate diverse groups, include community member perspectives and participation, and employ useful tools to structure and enhance their delivery and impact and improve program sustainability.

6.2 GAPS AND LIMITATIONS

In this section we will examine gaps in community mental health, including broad limitations and those specific to the three stages of community MHP practice: planning, implementation, and evaluation.

6.2.1 Introduction

Although the diversity of people and sub-settings within one community can bring many strengths to community MHP efforts (e.g., efforts wide-reaching, combining unique perspectives and abilities), they can also introduce barriers which vary between each individual setting. Widely consistent guidelines and recommendations for community MHP can therefore, be challenging to identify and enforce on large scales. Without a strong overarching research foundation, particularly regarding program implementation and evaluation, community MHP programs often struggle to achieve efficacy, feasibility, and sustainability (Barry, 2005). When studies are conducted in this field and shared with professionals, they can then take on an evidence-based approach to their programs. Learning what was successful and what was not during previous studies will avoid the use of continuous trial and error. Therefore, more comprehensive studies examining diverse populations, settings, methodologies, and influencing factors concerned with community MHP is needed to strengthen the lacking empirical foundation and enhance future programming using well-established best practices.

Identifying gaps, strengths, and helpful and harmful practices from existing research is an important step in guiding what new studies are needed to cement the empirical foundation of community MHP. Within existing studies, there has been a primary focus on specific rural communities with smaller populations (Barry, 2000; Mantovani & Gillard, 2017; Mathias et al., 2018), and little attention to the global use of MHP programming. Further comparative studies on a larger scale will provide best practices in a variety of different communities which identify trends within different common socioeconomic levels (Kohrt et al., 2018). Although broader comparative studies are needed, maintaining research within smaller communities is also essential, as they will supply information for comparative studies and collect information across diverse community settings and populations. Every community is different with a unique set of needs and specificity for programming, thus both levels of research are valuable, but more global studies should be conducted to synthesize the diverse practices being used. Using needs assessments or trial studies in more rural communities (Barry, 2000; Mathias et al., 2018; Rose & Thompson, 2012) will showcase in which areas MHP programs are excelling and what is working across diverse settings. Additionally, heavier focus on research mapping current program implementation and evaluation best practices will fill gaps in understanding and help streamline programming efforts (Barry, 2005). Following these next steps, guided by existing findings will help to address research gaps in a way that will support the community mental health program process across all three stages, as it will work to clarify the feasibility, necessity, effectiveness, and sustainability of community-level MHP programming. These benefits will improve and expand the success of MHP in communities around the globe, which enhances MHP on a widespread scale and provides justification to relevant stakeholders for continued funding and programming for community MHP.

6.2.2 Issues in Program Planning and Implementation

Assessing community needs and strengths: Going beyond needs assessments

Needs assessments are a commonly used tool during the planning stage to inform effective program implementation and evaluation in community MHP. Needs assessments have many strengths, but when they are skipped, or not created with the specific community or sub-population in mind, true community needs and issues may be overridden or remain unaddressed (Wright et al., 1998). A top-down approach which prioritizes non-community members opinions and misses addressing the community’s true needs, can be tokenistic or coercive and can have damaging impacts on the relationships between community members and mental health researchers and practitioners (Arnstein, 1969; Castillo et al., 2019). This is especially true when the needs of communities or sub-populations with distinct needs or histories of mistrust with healthcare are neglected or improperly collected (Castillo et al., 2019; Bauermeister et al., 2017). Following the needs assessments from the community is important to develop the directions of specific programming efforts, as these assessments will locate the areas in which further education and promotion would be most effective (Barry, 2000). It is vital that community MHP programs and those conducting them do not overlook the voices and participation of community members, especially during the planning stage, as the impacts of a non-community involved program plan could permeate throughout the entire programming process (Bauermeister et al., 2017).

Another barrier to overcome in relation to needs assessments is their problem-focused lens. Needs assessments are carried out to generate community information and perspectives on gaps or issues to be solved (Barry, 2000; Goodman et al., 1996). This focus on deficits can be useful for pinpointing needed points of support, however, it also opposes the strengths-focused nature of mental health promotion and misses out on opportunities to build on community strengths and empower community members through awareness and appreciation of these strengths (Whiting et al., 2012). Similar to how our understanding of mental health was enhanced by acknowledging the importance of positive mental health (Kobau et al., 2011), community mental health promotion may also benefit from tailoring needs-assessments to also focus on community strengths and from exploring new tools that are more strengths-based (Whiting et al., 2012).

Barriers to program success: accommodating diverse perspectives, resources, and needs

Although research document the success of community-based programming having a positive effect on the overall community, it is possible that a successful program model in one community would not transfer when implemented in another community. Every community is different and having an effective intervention setting is up to everyone involved in program planning and delivery (Burau et al., 2018). When designing the programs, determining the appropriate topics, settings, and involved groups poses a challenge that required careful consideration (Rose & Thompson, 2012). Even when the perspectives of people involved and the strengths, needs, and barriers are well-mapped, other issues can emerge when perspectives, needs, and available resources conflict. Community perspectives or needs do not align with available resources and/or the perspectives of mental health professionals. For example, the problem areas identified during the planning stage are not always achievable with the interventions of choice by the community. Additionally, when program settings are not diverse, there may be accessibility concerns in reaching all community members. These barriers can create conflicts between people involved (i.e., program facilitators, community-members, etc.), resulting in decreased investment or engagement from those whose perspectives are not prioritized, and/or decrease the feasibility of the program itself if it is not accommodated realistically to existing community resources and available settings.

Balancing community involvement with professional expertise

Each program has unique structures and aims which employ a variety of practitioners and professionals. This diversity is important to suit the needs of the specific program, population, and available community resources. Some existing programs prioritise primary healthcare providers and other mental health professionals (Ayano, 2018; Bell et al., 2007), which misses opportunities for beneficial community involvement and could result in community perspectives and needs being over-shadowed by expert opinion. Alternatively, programs may also be handed off to community members to deliver instead of professionals, especially as MHP expands. If communities are lucky, they may be able to rely on fellow community members who have received training in mental health advocacy and program facilitation, however, general community members remain less equipped to educate and advocate for mental health compared to professionals (Mantovani & Gillard, 2017), which can threaten program effectiveness. Community member-based programming (i.e., involves peer facilitators or mental health support-trained community members) has been proven to be an effective form of community MHP (Hill et al., “in press”; Mantovani & Gillard, 2017; Wagener et al., 2019). However, professionals in mental health education possess various skills and education that can only be achieved through highly specialized training that trained community members are unlikely to attain (Ayano, 2018). This is why striking a balance between community involvement and professional contribution will best maximize the benefits and mitigate the program-threatening limitations of both factors.

Sparsity of programming knowledge and practice in disadvantaged socio-cultural contexts

Those living in rural and low-socio-economic status communities are at higher risk for mental health struggles due to smaller populations, decreased resources, and low access to things needed to improve quality of life (Barry, 2000). Persons of colour are more likely than their white counterparts to experience persistent poor mental health with more severe symptoms, more impairment, and a lack of adequate mental health treatment (McMorrow et al., 2021). Despite evidence that certain groups experience poor mental health because of socio-cultural factors and established recommendations for MHP research and practice (i.e., Compton and Shim, 2015; Kirmayer et al., 2003), the translation of existing recommendations into practice has been limited. For example, little information is available on community-based initiatives that are explicitly created by, with, and for people of colour, and are preventive in nature (McMorrow et al., 2021). These issues are also seen the population-level, with limited MHP programming implemented in low-income countries, despite the more urgent need for healthcare support and demonstrated upstream health benefit of MHP approaches (Jané-LIopis et al., 2005). There is urgent action required to mitigate the harms which occur when systems and structures do not support the provision of mental health across diverse socities and cultures, and strengths-based community partnerships have power to play an instrumental role (Gopalkrishnan, 2018).

6.2.3 Limitations in the Evaluation Stage

Implementation evaluation vs outcome evaluation

Generally, program evaluation entails work that is mostly completed after the program delivery. This means evaluation is often based on outcomes (e.g., change in well-being before and after program delivery) instead of a more holistic measure of implementation effectiveness (Barry, 2005). This simplistic method is a limitation of MHP programming as the success of MHP programming is dependent upon the implementation process. However, if the analysis of these processes is not being evaluated, implementation will continue to stay the same and not improve the outcomes for participants. Community members take on the role of assisting in feedback or evaluation during the implementation so facilitators can make important adjustments to their success (Sacchetto et al., 2022). In addition, evaluating the success or failure of the program implementation can benefit the elimination of type 3 errors. Type 3 errors are situations where the implementation process used lacks quality delivery which invalidates the outcomes (Barry, 2007a). This is a continuous problem and could invalidate the entirety of the MHP programming. Since oftentimes community MHP is informal, evaluations suffer and do not provide accurate results. Community mental health has an array of methods for implementation and evaluation of every type, however, further research examining and evaluating the feasability and effectiveness of these methods would greatly benefit MHP programming across diverse community settings (Barry, 2007a; Barry, 2005).

Long-term effects of outcomes

Another area in which current practice and research are lacking is the effects of outcomes over time. Extensive evaluation of the effects over time, after the completion of the programming, will provide the long-term effects of outcomes and further rationale for the integration of community MHP programs. When an evaluation is conducted, it often exists shortly after the program is complete and then the program participants are never spoken to again. This provides basic information on the short-term effects, however, the long-term takeaways from participants are not often evaluated (Barry, 2005; Mathias et al., 2018). Regular documentation and consistent evaluation that extends past the completion of the intervention will provide the basis for the need for these interventions which will then promote sustainability over time (Barry, 2005). The overall goal of these interventions is to promote mental health and treatment to increase knowledge, promote positive mental health, and increase access to treatments available (Castillo et al., 2019; Jorm, 2012; Thornicroft et al., 2016). Although a simple questionnaire could determine this shortly after the completion of programs (Sacchetto et al., 2022), these effects are encouraged to last with the participant for the rest of their lives. To determine this, longitudinal studies of participant outcomes are necessary to determine the effectiveness of the interventions and support the sustainability of these efforts (Moodie & Jenkins, 2005).

We have learned that research in community mental health promotion has limited studies evaluating and integrating structured programming evaluation and implementation in the long-term, providing large scale synthesis of diverse program findings, and examining tailored programs and program barriers within diverse and/or disadvantaged populations. The comparative effectiveness and practical guidance for different ways that community programs should involve various stakeholders (i.e., healthcare providers, health promoters, policy-makers, community members) to foster collaborative partnerships is also limited.

6.3 FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

This section will discuss several areas for future research and action needed to address existing limitations and improve the study and practice of community mental health promotion. These include identifying community-specific factors impacting MHP programming, diversifying research and practice across community populations and settings, maximizing professional and community involvement in MHP, and refining tools to enhance their utility in community MHP programming.

6.3.1 Acknowledging Community-Specific Factors impacting Mental Health Promotion

Communities are all unique in and often include diverse populations and settings. Acknowledging and researching individual-community level factors and needs are essential for program implementation and success across each distinct community. Many of these components will be unique to each community and will not entirely benefit from a one-size fits all approach. Intensive planning and on-going monitoring must, therefore, be conducted periodically to identify and track any relevant barriers and/or strengths impacting the program and in the broader community while the program is active. Efforts to identify and account for these factors can involve tailoring MHP programming based on a community’s needs-assessment, careful consideration and identification of all potential community-specific implementation barriers, or use of active participation methods to incorporate community members unique perspectives throughout all stages of MHP programming.

Identifying program-impacting factors provides useful data on what is working and what is not, as well as clarify factors relevant within each stage of programming in a distinct community (Barry, 2005). These can include barriers, strengths, or important considerations. Working with these distinct factors and adapting as fit, is the most successful way to build and implement program for the specific community (Barry, 2007a; Thornicroft et al., 2016). Some factors identified from previous programs range from socioeconomic status (Kohrt et al., 2018), to accessibility to program spaces (Rose & Thompson, 2012), to preconceived ideas of MHP (Burau et al., 2018). Examining community-specific factors that influence programming and identifying useful existing resources can enhance the feasibility and success of a program across all stages of programming. Although generalized barriers, strengths, and considerations will continue be revealed through future research, the uniqueness of each community purports that researchers and MHP practitioners do not only rely only on existing research and older knowledge to inform a new programming project. This is also important, given that communities, influencing factors, and existing MHP tools and knowledge change over time. For example, social media and technology use is increasingly popular and can impact mental health in many ways, both positive and negative (Braghieri et al., 2022). Thus, social media and technology use exemplify factors that grew into relevance in community mental health programming, whether it be using technology as a means for aspects of program delivery (e.g., intervention apps, program work delivery) or as an indicator of community members’ mental health (REF; Hill et al., “in press”). Careful consideration should be used when determining the best and most current approaches and practices, to ultimately increase effectiveness and sustainability of a program within each unique community.

6.3.2 Diversifying Research and Practice across Various Populations and Settings

While individual-community level strategies are important, they require intensive efforts and research, which is costly and often generate programs that are very-specific to one community’s sub-populations needs. Refining and reviewing factors which are broadly and consistently effective (i.e., inclusive, diverse settings and broad populations) and are also consistently ignored and/or cause harm may inform more efficient and feasible methods and areas to adjust for effective program planning and implementation across various community populations and settings.

Identifying target-populations for maximized community MHP reach

One widely consistent and urgent target population for community MHP programming are youth and adolescents, as this age-group experiences high rates of mental health challenges and adverse outcomes from them (Shatkin & Belfer, 2004; Shastri, 2009). Hurley et al. (2017) examined the role of community sports and adolescent mental health, finding this area had a large positive influence on youth and their mental health opinions and beliefs. Further, these programs can incorporate broader participation and enhanced outcomes by involving parents (Hurley et al., 2017). Programs targeting broad community populations like youth and adolescents have the potential to be highly effective in both promoting positive mental health and garnering other benefits for community members. For example, the program benefits for adolescents and parents described above may also offer early prevention of mental health challenges for youth participants and increased mental health literacy in families, which could extend into adulthood and enhance the community in lasting ways (Jorm, 2012; Shastri, 2009). Thus, additional research should continue to identify broad community demographics to allows programs and their benefits to be widely applicable and inclusive to community members.

Exploring community settings and resources for enhanced community programming

Expanding the limited diversity of community settings used for MHP programming may help to enhance programming efforts and make programs more widely available to broader populations of community members. If formal MHP programming is piloted in diverse settings, it could bring enhanced benefits through improved accessibility and inclusion within communities and heightened feasibility through identifying which settings suit specific community programs and needs. Additionally, many communities have common, pre-existing community-based resources, (e.g., programs, settings, etc.) that already develop a focus on the promotion of mental health. For example, Jones et al. (2013) looked at pre-existing community-based arts and leisure programs and found that MHP efforts can be integrated into this setting. Hurley et al. (2017) found that sports clubs can foster positive mental health for adolescents from the perspective of their parents/caregivers. In addition to diversifying and exploring many potential program settings, building off existing community settings and resources can also enhance programming. Using these pre-existing resources may foster more comfort and facilitated participation from community members and improving feasibility by saving time and costs spent on identifying and securing new settings. Further research is needed examining perspectives of community members who do not use typical community MHP program settings (i.e., community centres, arts and leisure programs, and sports facilities) to ensure accessibility and inclusion. Additionally, continued analysis of the challenges and drivers of integration of MHP into unique communities will reveal settings that are most consistently effective (Burau et al., 2018; Sacchetto et al., 2022). Evaluation of diverse settings options and programs using them could use representative sampling to assess the perspectives and diverse program outcomes based on all individuals who live, work, and play in their communities.

Ensuring equitable community MHP across all community populations

In addition to targeting diverse and widely useful populations and settings community MHP programs need to be enhanced, applied, and evaluated in various cultural contexts and within disadvantaged demographic groupings, in order to properly achieve the goal of inclusively promoting positive mental health (Barry, 2007a). This includes enhancing programming in developing countries and research and adaptations of programming best suited to socially disadvantaged groups and/or ethno-cultural minorities (Castillo et al., 2019; Gopalkrishnan, 2018). Most MHP research is conducted within developed countries, where socio-cultural considerations are comparatively more oriented towards demographic majority populations. New approaches must be taken to employ unique considerations and program adjustments required for specific socially or culturally diverse populations (e.g., specific ethno-cultural groups, Gopalkrishnan, 2018). Although cultural competence approaches have been a prominent tool, they are limited by a value-neutral position and limited participation of community members (Gopalkrishnan, 2018). Going beyond these approaches to foster partnerships between diverse cultural communities and healthcare providers is thought extend beyond the limitations of competence-based approaches. For example, implementation of two-way knowledge sharing practices into programs among Indigenous populations (i.e., Two-eyed seeing; Kirmayer et al., 2003). Future research should continue to evaluate opportunities to achieve these partnerships within unique social and cultural community MHP contexts. Further, to avoid unintentionally worsening stigma among any of these social or culturally disadvantaged populations, research on interventions for at-risk people with any stigmatised condition should establish trust and on-going collaboration with participants (Bauermeister et al., 2017; Castillo et al., 2019). Additionally, the structural forces that put certain populations at higher risk for adverse conditions, such as discriminatory policing and housing policies, must be also acknowledged in community MHP programming (Castillo et al., 2019). Lastly, it is vital to ensure that ethical, culturally competent, and partnered methods are employed at all stages of community MHP carried out in diverse populations and communities (Bauermeister et al., 2017; Castillo et al., 2019; Gopalkrishnan, 2018).

6.3.3 Maximizing Professional and Community Involvement in Community MHP

To promote successful implementation and stability, research should also concentrate on striking a balance between professional and community involvement in MHP programming. By maintaining professional involvement in community settings, MHP remains truly upstream – a preventative measure instead of treatment based. However, continued collaboration, and consultation with community members is important to ensure the fulfillment of community members perspectives and needs (Bauermeister et al., 2017; Mantovani & Gillard, 2017). Finding a balance between community involvement and professional contribution maximizes expert knowledge without overruling community perspectives, while also leveraging the unique strengths brought in by active community participation. This balance can be leveraged by partnerships and collaboration (Thompson et al., 2016), however, specific practices will shift depending on the program settings and structure, as well as the perspectives and aims of both community members and MHP practitioners. For example, in many countries there is limited capacity for the formal healthcare system to address mental health issues, so it makes sense to look to the wider community to support to supplement mainstream health care options. However, it remains unclear whether maximized benefit of community MHP programming is best achieved through emphasizing active community involvement, trained community mental health facilitation, or the heightened involvement of healthcare providers and practitioners into the community. Future investigation is needed to examine what training is needed to build well-equipped community member mental health advocates, as they initially lack the communication skills to talk about mental health (Mantovani & Gillard, 2017). Additionally, research comparing communities with community member mental health advocates and/or program facilitators compared to integrated healthcare practitioners as mental health advocates or program facilitators may clarify which approach is truly more effective and upstream in preventing and promoting positive mental health in the community.

Identifying sources and strengths for contributions to MHP programming

Before exploring the benefits and scope of potential partnerships and collaboration, research and practice must also continue to examine and involve under-utilized groups or skills of MHP professionals and/or community members. This guides the capitalization of community and professional strengths through illuminating new possible roles or contributions from community members or known health professionals as well as revealing new groups or people who could contribute to community MHP efforts. One study found that pharmacists can play an important role as members of community mental health teams by conducting pharmacological treatment programs that meet a significant public health need (Bell et al., 2007). Other studies examined the role teachers and coaches can play in the promotion, prevention, and early intervention in youth mental health and found that both are supportive of mental health by providing activities for young people (Mazzer & Rickwood, 2013; Jones et al., 2013). More research using different methodologies should examine already-identified groups and aim to identify other relevant groups of MHP experts or community members, to reveal how each group can most effectively be involved in promoting mental health at the community-level.

Maximizing the benefits through collaboration and partnerships

After various groups and their most useful strengths and MHP contributions are identified, research is needed to inform and comprehend the efficacy of partnerships between the members of the community, providers, and researchers. Collaboration within various groups of health and MHP experts provides further opportunity to enhance community MHP (Ravaghi et al., 2023). The combined expertise from multiple experts in different domains of mental health promotion helps to settle disagreements and inform the best courses of action in next steps for community MHP. This is highly beneficial for collaborative synergy and consensus between policymakers, researchers, and other stakeholders involved in community MHP, which facilitates action taken to improve mental health promotion (Raeburn et al., 2006; Thompson et al., 2016). The exchange of knowledge between community MHP practitioners, community members, and policymakers also ensures that policymakers receive feedback about existing frameworks and can adjust accordingly to create policies which permit community MHP to thrive (Thompson et al., 2016). These partnerships and their outcomes advocate for community MHP programs and broader mental health services to be feasible, available, and oriented towards community needs (Carmola & Bond, 2002; Jung & Aguilar, 2015; Thompson et al., 2016).

Collaborations should also aim to enhance mental health competencies in community programming to effectively enhance MHP efforts (Mathias et al., 2018). Collaboration with health professionals provides perspective to community mental health advocates and/or program facilitators which ensures they are equipped to deliver and/or promote MHP programs (Ayano, 2018; Bell et al., 2007a; Tambyah et al., 2022). Often, primary health providers (e.g., doctors) are the first people in which community members will seek treatment for mental health conditions. Thus, primary health providers within the community can collaborate with mental health professionals to prioritise the best education and tools for program facilitators and/or community members (Burau et al., 2018). When collaborations incorporate community members, they extend across multiple socio-ecological levels to promote mental health and mobilize all involved parties (i.e., community members, program facilitators, community health providers, etc.) in community MHP (Jorm, 2012: Mathias et al., 2018). Working with community members is also essential for community MHP researchers and program facilitators in maintaining trust, fostering participation, empowerment, and community mental health literacy, and ensuring MHP efforts match the community’s needs (Jorm, 2012; Thompson et al., 2016). Incorporating either peers or providers in a facilitating role has been identified as a successful feature of community mental health programs and community involvement and participation has been identified as a major facilitator in community health research and practice (Hill et al., “in press; Ravaghi et al., 2023). Continuous collaboration with a variety of groups ensures that mental health programming is accessible, sustainable, and reflective of the needs within the community.

6.3.4 Advocating for and Improving Programs by Enhancing Existing Tools

Asset-based approaches and needs assessments

Needs assessment acted as one of the most beneficial tools used in determining the specific needs of a rural Irish community, as are recommended as useful across multiple socio-ecological settings (Barry, 2000; Goodman et al., 1996). However, the problem or needs focus of these assessments demonstrates a need for exploration of other tools or assessment variations to better align with the strengths-based approach of mental health promotion and maximize community strengths within community MHP programming. The idea for incorporating asset-based approaches originated from this realization and involves collecting information on and enhancing community strengths to achieve community goals (Whiting et al., 2012). The added incorporation of such strengths-based approaches (i.e., appreciative inquiry, community asset-mapping) provides additional MHP program planning methods, as well as inform new approaches to implementation and evaluation that benefit from previously unrealized community strengths (Ravaghi et al., 2023). Future research should focus on evaluating other tools for mapping community needs, strengths, and opportunities, (e.g., tailoring different types of needs assessments), incorporating new means of investigating and leveraging community-specific factors that are strengths-focused (e.g., asset-mapping), and examining which forms of MHP programs and communities benefit most from these methods to inform their use in practice. Additionally, there is a need for more mixed-methods research clarifying the definitions and methodological and logistic barriers and facilitators of both asset-based and needs-based approaches in community health (Ravaghi et al., 2023).

Updated logic models for refining program evaluation

Program evaluation is a stage of community MHP that seriously needs further study (Barry, 2003). Logic models provide a set framework which can be useful in guiding practice and monitoring outcomes through research, to address existing limitations. For program evaluation these limitations include lacking evaluation of long-term program effects and limited distinction between different methods and aims of evaluation (i.e., evaluating implementation effectiveness, or program benefits on community mental health. Utilizing comprehensive and evidence-based logic models such as the evaluation logic model from Barry (2003) may help to address limitations relating to long-term effects and specificity of evaluation type. This model provides four distinct components for effective evaluation (i.e., project inputs, process evaluation, impact evaluation, and outcome evaluation; see Figure 1). Integrating logic models and other means to guide research and practice throughout each stage of community MHP programming provides a specific framework useful for clarifying evaluation methods within the broader programming and research process, which addresses existing evaluation limitations and will provide practical knowledge guiding future program delivery to be more feasible and sustainable (Barry, 2003; Barry, 2005).

6.3.5 Conclusion

This chapter outlined the challenges associated with implementing community MHP programs, and highlighted factors to consider when developing programs during the planning, implementation, and evaluation stage. Features and tools that can improve programs were identified, including needs and asset-based assessments, incorporating partnership and collaboration, and ensuring programs are socially and culturally tailored. Considering these features and tools and implementing them into community MHP programs at all stages, can help to combat the challenges associated with community MHP and create more effective, feasible, and sustainable programs. However, limited implementation and evaluation research and large-scale synthesis studies largely contributes to persisting gaps in programming, which challenge both the practice of MHP and understanding required to enhance and rationalize it. Future study and practice should clarify and implement best practices (i.e., mental health education, policy reviews) for multi-sector partnerships and collaborations and identify the kinds of social and health issues that can most benefit from community-based projects (Barry, 207a; Castillo et al., 2019). This might include examining and incorporating contributions and collaboration between policymakers, mental health advocates, community members, and stakeholders in community MHP programs. More research is also needed into the effectiveness of MHP programs and how they can be tailored to and modified to the specific needs and requirements of a community (Barry, 2000). This involves simultaneous efforts to identify factors in programming which are widely useful, while also ensuring implemented programs are best suited to specific communities and settings and are equitably distributed where they are most needed (i.e., low-income countries; Barry, 2005; Jané-LIopis et al., 2005). Across the three stages of MHP programming, more focus on the implementation and evaluation steps is needed to best assess successes and effectiveness of various programming efforts (Barry, 2005; Barry; 2007a). Further, existing tools may provide practical support to the practice of current programs, while new research works to establish a more solid evidence base and discover new facilitators, settings, and strategies to enhance MHP in the community.

In this section we have uncovered the need for future research by determining community needs and finding innovative ways for program evaluation and advocate education.