3.5 Nucleic Acids

KEY CONCEPTS

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe nucleic acids’ structure and define the two types of nucleic acids

- Explain DNA’s structure and role

- Explain RNA’s structure and roles

Nucleic acids are the most important macromolecules for the continuity of life. They carry the cell’s genetic blueprint and carry instructions for its functioning.

DNA and RNA

The two main types of nucleic acids are deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). DNA is the genetic material in all living organisms, ranging from single-celled bacteria to multicellular mammals. It is in the nucleus of eukaryotes and in the organelles, chloroplasts, and mitochondria. In prokaryotes, the DNA is not enclosed in a membranous envelope.

The cell’s entire genetic content is its genome, and the study of genomes is genomics. In eukaryotic cells but not in prokaryotes, DNA forms a complex with histone proteins to form chromatin, the substance of eukaryotic chromosomes. A chromosome may contain tens of thousands of genes. Many genes contain the information to make protein products. Other genes code for RNA products. DNA controls all of the cellular activities by turning the genes “on” or “off.”

The other type of nucleic acid, RNA, is mostly involved in protein synthesis. The DNA molecules never leave the nucleus but instead use an intermediary to communicate with the rest of the cell. This intermediary is the messenger RNA (mRNA). Other types of RNA—like rRNA, tRNA, and microRNA—are involved in protein synthesis and its regulation.

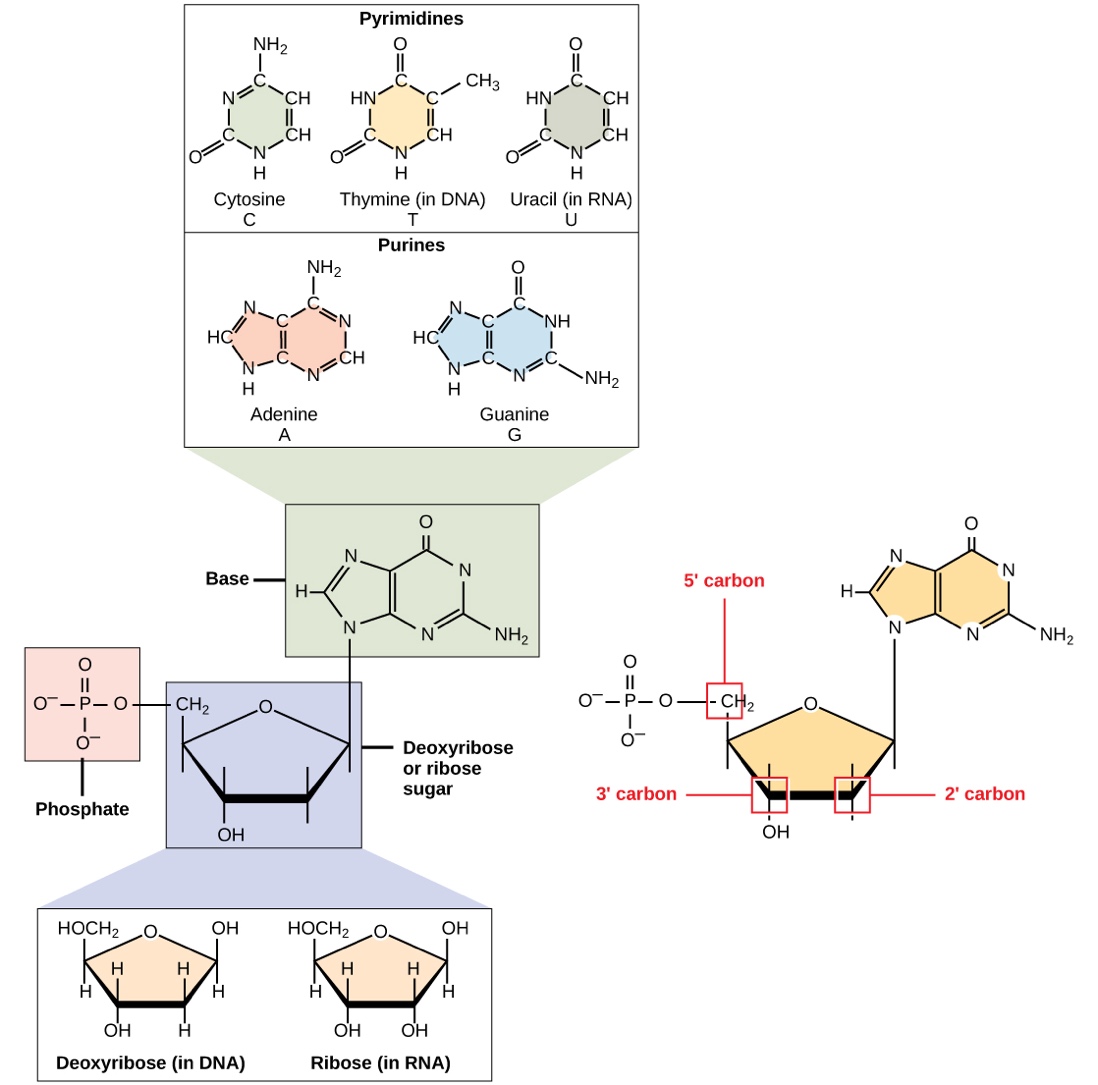

DNA and RNA are comprised of monomers that scientists call nucleotides. The nucleotides combine with each other to form a polynucleotide, DNA or RNA. Three components comprise each nucleotide: a nitrogenous base, a pentose (five-carbon) sugar, and a phosphate group (Figure 3.31). Each nitrogenous base in a nucleotide is attached to a sugar molecule, which is attached to one or more phosphate groups.

The nitrogenous bases, important components of nucleotides, are organic molecules and are so named because they contain carbon and nitrogen. They are bases because they contain an amino group that has the potential of binding an extra hydrogen, and thus decreasing the hydrogen ion concentration in its environment, making it more basic. Each nucleotide in DNA contains one of four possible nitrogenous bases: adenine (A), guanine (G) cytosine (C), and thymine (T).

Scientists classify adenine and guanine as purines. The purine’s primary structure is two carbon-nitrogen rings. Scientists classify cytosine, thymine, and uracil as pyrimidines which have a single carbon-nitrogen ring as their primary structure (Figure 3.31). Each of these basic carbon-nitrogen rings has different functional groups attached to it. In molecular biology shorthand, we know the nitrogenous bases by their symbols A, T, G, C, and U. DNA contains A, T, G, and C; whereas, RNA contains A, U, G, and C.

The pentose sugar in DNA is deoxyribose, and in RNA, the sugar is ribose (Figure 3.31). The difference between the sugars is the presence of the hydroxyl group on the ribose’s second carbon and hydrogen on the deoxyribose’s second carbon. The carbon atoms of the sugar molecule are numbered as 1′, 2′, 3′, 4′, and 5′ (1′ is read as “one prime”). The phosphate residue attaches to the hydroxyl group of the 5′ carbon of one sugar and the hydroxyl group of the 3′ carbon of the sugar of the next nucleotide, which forms a 5′–3′ phosphodiester linkage. A simple dehydration reaction like the other linkages connecting monomers in macromolecules does not form the phosphodiester linkage. Its formation involves removing two phosphate groups. A polynucleotide may have thousands of such phosphodiester linkages.

DNA Double-Helix Structure

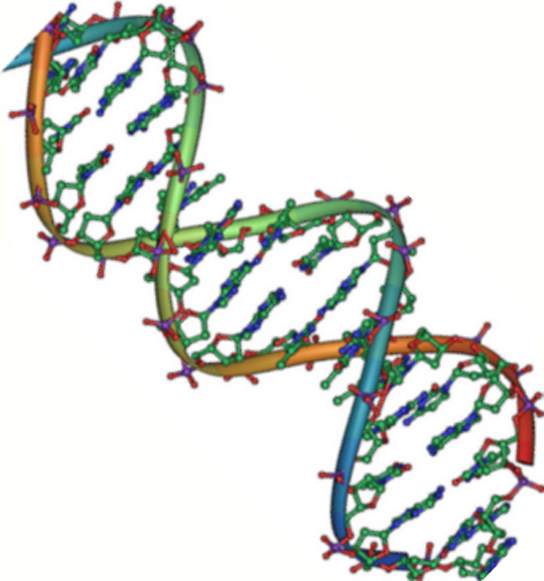

DNA has a double-helix structure (Figure 3.32). The sugar and phosphate lie on the outside of the helix, forming the DNA’s backbone. The nitrogenous bases are stacked in the interior, like a pair of staircase steps. Hydrogen bonds bind the pairs to each other. Every base pair in the double helix is separated from the next base pair by 0.34 nm. The helix’s two strands run in opposite directions, meaning that the 5′ carbon end of one strand will face the 3′ carbon end of its matching strand. (Scientists call this an antiparallel orientation and is important to DNA replication and in many nucleic acid interactions.)

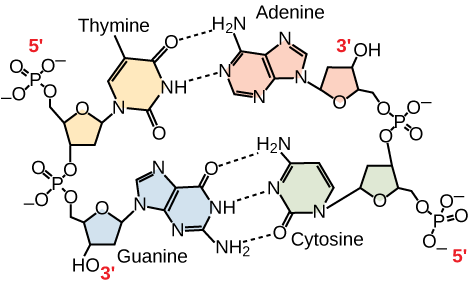

Only certain types of base pairing are allowed. For example, a certain purine can only pair with a certain pyrimidine. This means A can pair with T, and G can pair with C, as Figure 3.33 shows. This is the base complementary rule. In other words, the DNA strands are complementary to each other. If the sequence of one strand is AATTGGCC, the complementary strand would have the sequence TTAACCGG. During DNA replication, each strand copies itself, resulting in a daughter DNA double helix containing one parental DNA strand and a newly synthesized strand.

Visual Connection

RNA

Ribonucleic acid, or RNA, is mainly involved in the process of protein synthesis under the direction of DNA. RNA is usually single-stranded and is comprised of ribonucleotides that are linked by phosphodiester bonds. A ribonucleotide in the RNA chain contains ribose (the pentose sugar), one of the four nitrogenous bases (A, U, G, and C), and the phosphate group.

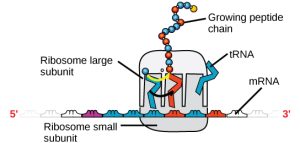

There are four major types of RNA: messenger RNA (mRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), and microRNA (miRNA). The first, mRNA, carries the message from DNA, which controls all of the cellular activities in a cell. If a cell requires synthesizing a certain protein, the gene for this product turns “on” and the messenger RNA synthesizes in the nucleus. The RNA base sequence is complementary to the DNA’s coding sequence from which it has been copied. However, in RNA, the base T is absent and U is present instead. If the DNA strand has a sequence AATTGCGC, the sequence of the complementary RNA is UUAACGCG. In the cytoplasm, the mRNA interacts with ribosomes and other cellular machinery (Figure 3.34).

The mRNA is read in sets of three bases known as codons. Each codon codes for a single amino acid. In this way, the mRNA is read and the protein product is made. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is a major constituent of ribosomes on which the mRNA binds. The rRNA ensures the proper alignment of the mRNA and the Ribosomes. The ribosome’s rRNA also has an enzymatic activity (peptidyl transferase) and catalyzes peptide bond formation between two aligned amino acids. Transfer RNA (tRNA) is one of the smallest of the four types of RNA, usually 70–90 nucleotides long. It carries the correct amino acid to the protein synthesis site. It is the base pairing between the tRNA and mRNA that allows for the correct amino acid to insert itself in the polypeptide chain. MicroRNAs are the smallest RNA molecules and their role involves regulating gene expression by interfering with the expression of certain mRNA messages. Table 3.2 summarizes DNA and RNA features.

Table 3.2 DNA and RNA Features

|

|

DNA |

RNA |

|

Function |

Carries genetic information |

Involved in protein synthesis |

|

Location |

Remains in the nucleus |

Leaves the nucleus |

|

Structure |

Double helix |

Usually single-stranded |

|

Sugar |

Deoxyribose |

Ribose |

|

Pyrimidines |

Cytosine, thymine |

Cytosine, uracil |

|

Purines |

Adenine, guanine |

Adenine, guanine

|

Even though the RNA is single stranded, most RNA types show extensive intramolecular base pairing between complementary sequences, creating a predictable three-dimensional structure essential for their function.

As you have learned, information flow in an organism takes place from DNA to RNA to protein. DNA dictates the structure of mRNA in a process scientists call transcription, and RNA dictates the protein’s structure in a process scientists call translation. This is the Central Dogma of Life, which holds true for all organisms; however, exceptions to the rule occur in connection with viral infections.

Links to Learning

To learn more about DNA, explore the Howard Hughes Medical Institute BioInteractive animations on the topic of DNA.

Review video from Crash Course Biology: Biological Molecules – You are What You Eat