1.2 Prokaryotic Cells and Evolution

KEY CONCEPTS

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Have a basic understanding of prokaryotic cell structure, and the diversity in this structure

- Be familiar with the origins of cells, understanding concepts such as abiogenesis, protocells, the RNA World hypothesis, and LUCA

Diversity in Prokaryotic Cells

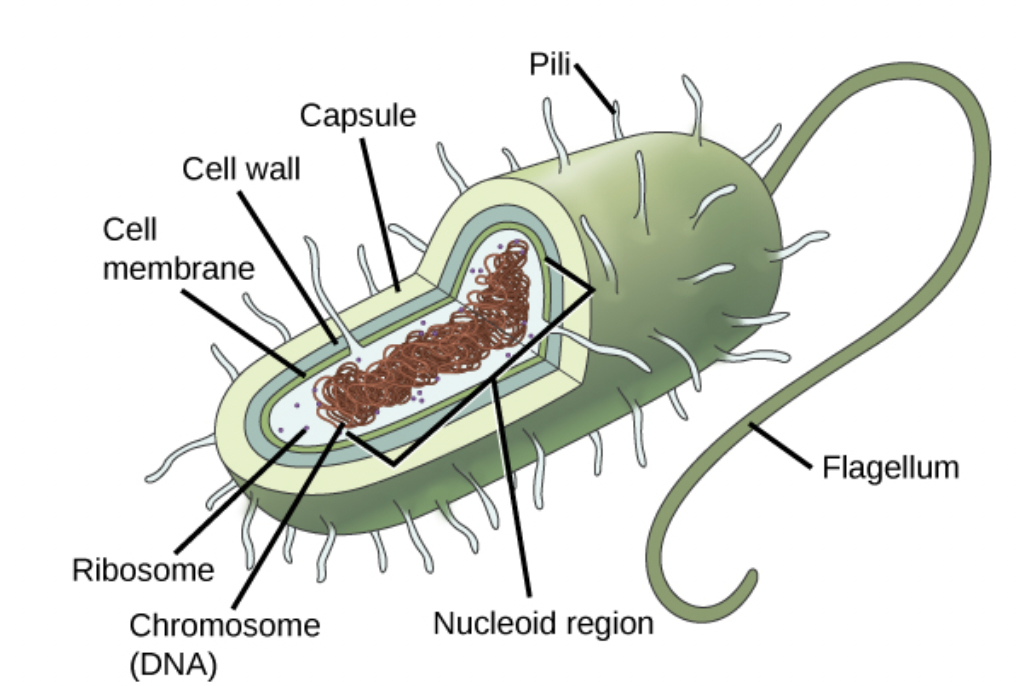

Before discussing the evolution of prokaryotic cells, we must quickly review their structure and diversity. In addition to the common components of all cells (a plasma membrane, cytoplasm, DNA, and ribosomes), there are a few additional components of cell structure we can consider. Since prokaryotes lack a nucleus, their DNA is in the cell’s central region, known as the nucleoid (Figure 1.4). Most prokaryotes have a peptidoglycan cell wall that is extracellular (i.e., outside the cell membrane). The cell wall acts as an extra layer of protection, helps the cell maintain its shape, and prevents dehydration. Some prokaryotes have an additional outer membrane, extracellular to the cell wall. Many prokaryotes also have a polysaccharide capsule, or slime capsule (Figure 1.4). The capsule enables the cell to attach to surfaces in its environment. Some prokaryotes have flagella, pili, or fimbriae. Flagella (singular: flagellum) are used for locomotion. Sex pili (singular: pilus) allow prokaryotes to exchange genetic material with each other during conjugation, the process by which one bacterium transfers DNA to another through direct contact. Some bacteria can use fimbriae (singular: fimbria), which are a type of pili, to attach to other cells. For example, some pathogenic (disease-causing) bacteria can use fimbriae to attach to a host (e.g. human) cell.

Despite the simplicity of their structure, prokaryotes are very diverse. With billions of years of evolution behind them, prokaryotes range in shape, size, and types of metabolic pathways. While some prokaryotes are round, others are rod-shaped. Some prokaryotes need oxygen for their metabolic pathways (e.g., obligate aerobes), while others die in environments where oxygen is present (e.g., obligate anaerobes). Some prokaryotes have very specialized adaptations that allow them to live in extreme environments. For example, some species of Archaea are thermophilic, thriving in very hot (>60°C) environments like hot springs. Prokaryotes also have a wide range of relationships to humans; some inhabit our intestinal tract, helping us digest our foods, while some can cause severe illness or even death when they come in contact with humans. This is just a simple overview of the diversity of prokaryotic cells.

Evolution of Prokaryotes

Prokaryotic cells are thought to be the first self-sufficient living organisms to exist, and arose an estimated 3.9 billion years ago. Although we can’t be sure how these organisms came to be, a series of hypotheses have been made regarding the evolution of our planet’s first life forms. For cells to evolve, first the building blocks of common biomolecules must be available in the environment. These common biomolecules include those that are important for cell structure like membrane lipids. A core principle of evolution is that genetic information must be passed from generation to generation, so the evolution of cells also required a biomolecule that could contain genetic information like DNA or RNA. Given the widespread use of ribosomes to make proteins in all modern cells, the building blocks for proteins (amino acids) must have also arisen at some point. Similarly, most cells can use carbohydrates (sugars) as an energy source, so the metabolism surrounding these biomolecules likely arose early in prokaryotic evolutionary history. If these biomolecules were compartmentalized (trapped) into cell-like structures, evolution by natural selection on these protocells (or early cells) could have gradually given rise to the prokaryotes we know today. This section of the chapter will explore some of the evidence for these early steps in prokaryotic evolution, leading to the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), from which all modern cells are descended (Figure 1.2).

Abiogenesis: 4.2 billion years ago

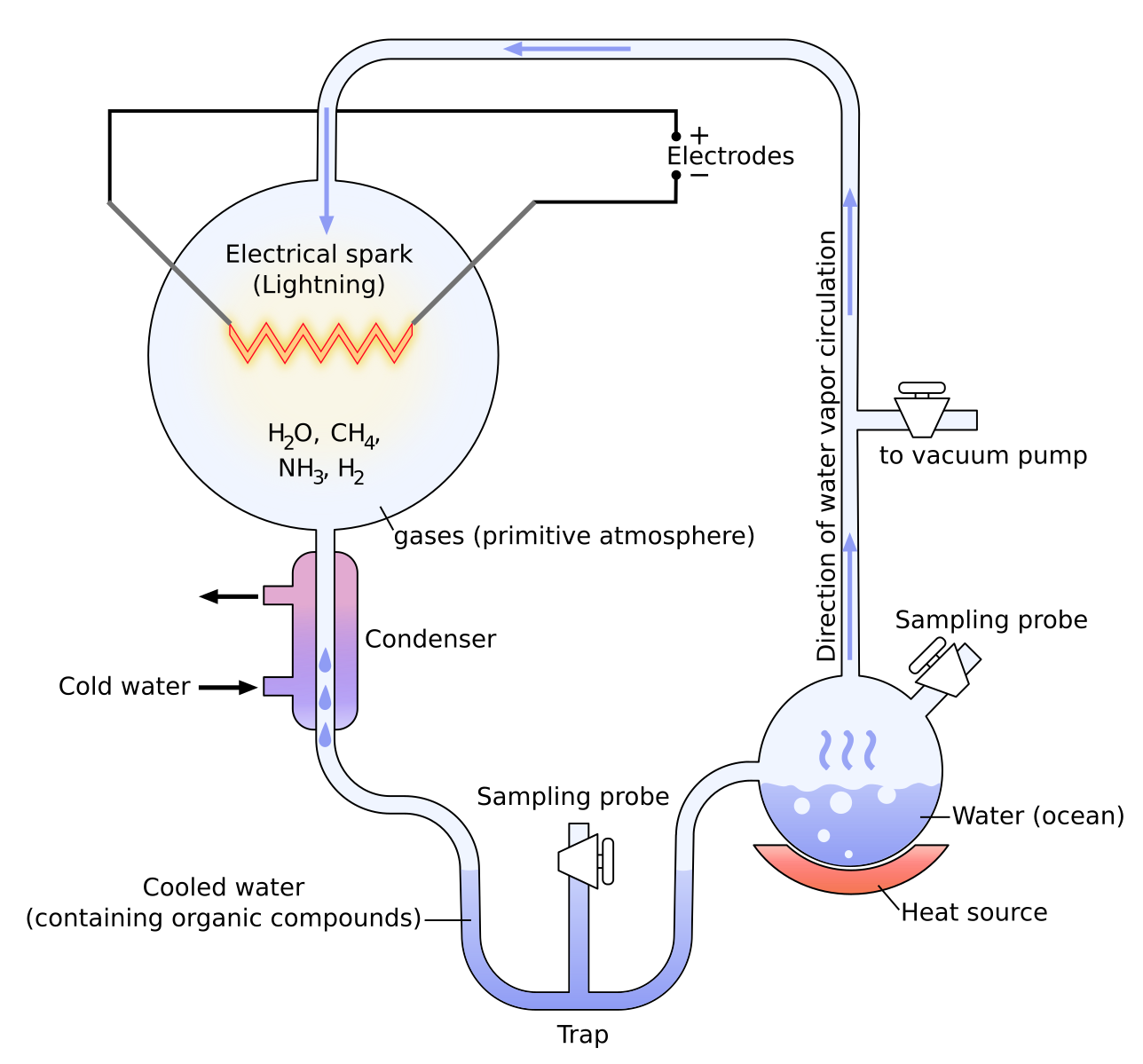

Although one of the central tenets to cell theory is that all cells arise from pre-existing cells, that cannot be true for the very first cell that evolved. In a world with no life, the first living organism must have evolved from abiotic (non-living) things via a process known as abiogenesis. For cellular life to arise, first the synthesis of biological macromolecules or their precursors must occur, which likely began about 4.2 billion years ago. The production of various organic compounds can form from inorganic precursors, as shown in the classic Urey-Miller experiment (Figure 1.5). By providing water (H2O), hydrogen (H2), ammonia (NH3), and methane (CH4) – compounds thought to be present in the early earth’s atmosphere – and an energy source (electric sparks), Miller and Urey showed that amino acids, aldehydes (basis of sugars), and other organic compounds (e.g. lactic acid) could form within 1 – 2 weeks. While this experiment likely does not exactly mimic the history of abiogenesis, Urey and Miller proved abiogenesis was possible in the absence of cells, and their work has since been replicated.

There are at least two hypotheses of what sources provided the energy required for abiogenesis to occur. The first is UV light hitting the surface of the earth. When abiogenesis was thought to be occurring, the earth’s ozone layers were not yet formed, meaning the intensity of light that was hitting the surface of the earth was much greater than it is today. The energy of this UV light could have driven the reactions required for the formation of biological macromolecules.

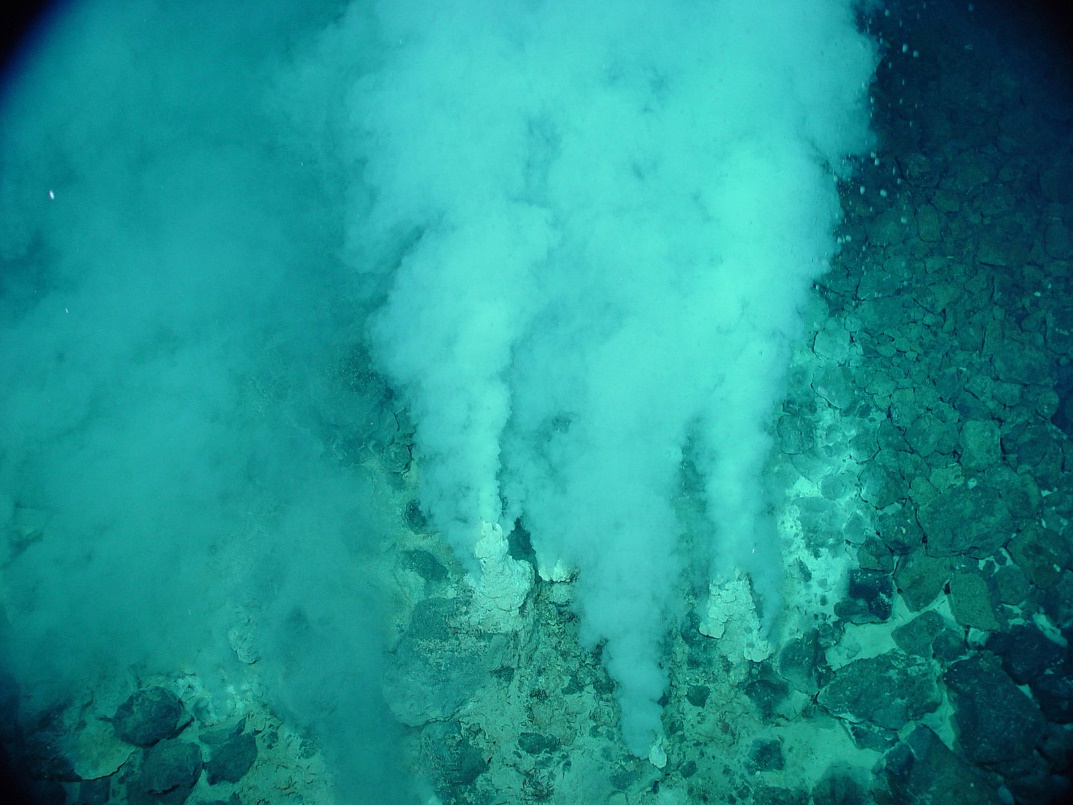

The second hypothesis is that hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the oceans were the energy source for abiogenesis (Figure 1.6). It is thought that the hydrothermal vents had concentrated sources of inorganic material, which with the help of the heat of hydrothermal vents, reacted to form the first biological macromolecules. Evidence suggests that the deep ocean would have protected these biomolecules from the intense UV radiation. These molecules could also be trapped in mineral pores, allowing compartmentalization of biomolecules and their precursors prior to the development of lipid membranes.

Protocells: < 4.2 billion years ago

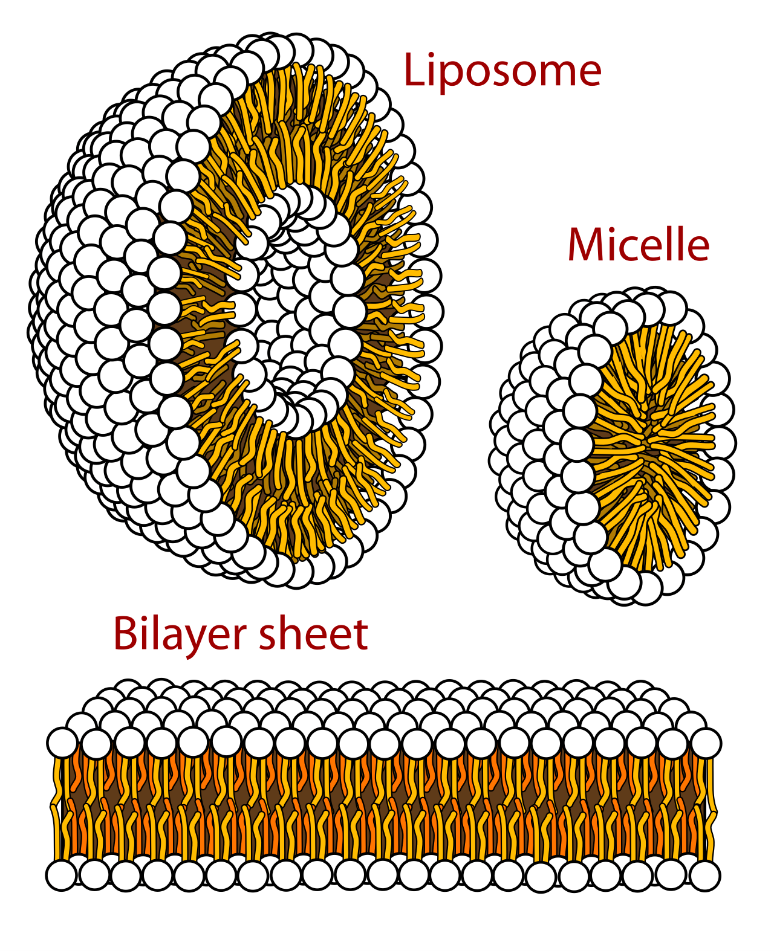

Protocells are precursors to cells that are formed by the self-assembly of amphiphilic lipids into a micelle or liposome (small membrane-bound spheres). These protocells may have arisen soon after abiogenesis, or later in evolution – it is not yet clear. Amphiphilic molecules have a polar end that interacts well with water, and a nonpolar end that repels water. An example of this type of molecule in modern cells is phospholipids. Amphiphilic molecules naturally organize themselves in a way that protects the non-polar ends from water due to the hydrophobic effect, which can result in the formation of a membrane between the abiotic and biotic environments (Figure 1.7). By creating an internal environment that was separate from the external environment, protocells could compartmentalize biomolecules into a smaller space, increasing the concentration of biomolecules and the likelihood of chained series of biochemical reactions (metabolism) occurring. These early membranes that surrounded protocells were likely semipermeable, only allowing certain molecules to pass through. Therefore, the environment inside protocells was different from the external environment, likely permitting the synthesis of additional biomolecules that could potentially support cellular life.

RNA World: 4 billion years ago

Once basic life forms started to emerge, there was only one thing left to do, which was to make more life. For this to occur, information encoding for the building blocks of new life must be stored and transferred from generation to generation. Modern cells use DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) to store information and transmit genetic information. However, it is hypothesised about 4 billion years ago, the first cells used RNA (ribonucleic acid), to store and transmit genetic information. While RNA is less stable than DNA, RNA has one feature that makes it a more likely carrier of genetic information in early information: RNA is able to catalyze chemical reactions. For example, modern RNA in ribosomes help catalyze the formation of bonds between amino acids and proteins. Modern cells still use RNA as a part of their transcription and translation processes.

The RNA world hypothesis suggests that the simple strands of RNA were responsible for the first forms of replication of living organisms. Support for this hypothesis has grown with the discovery of RNA’s ability to self-replicate (replication without DNA). In laboratory settings, it has been demonstrated that RNA is capable of self-cleavage and can autocatalyze its own synthesis, where it can act as a template strand for its own replication. Free nucleotides can bind to their base pairs from the original single stranded RNA, forming a new strand. Because of the instability of RNA, these two strands are easily separated when exposed to heat, allowing new nucleotides acids to bind to the single strands, allowing the cycle of self-replication to occur.

Links to Learning

A deeper look at the RNA world hypothesis.

Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA): 3.9 billion years ago

Once self-replicating protocells with RNA existed, life had the raw ingredients for evolution of the first prokaryotes. One mechanisms of evolution is natural selection. Evolution by natural selection occurs when there is variation within a population and that variation is heritable. That population may be a population of cells, protocells, or even RNA molecules alone. Individuals in the population with certain traits are more successful at reproducing, increasing their fitness (number of offspring produced), increasing the frequency of the favoured trait in future generations. As individuals accumulate different mutations (variation) in their genetic material, an individual species may eventually diverge into two species with slightly different characteristics. It is because of evolution that we have millions of species on earth today. It is thought that the lineages of all living organisms today evolved from a single organism or population of organisms known as LUCA (Last Universal Common Ancestor; Figure 1.2). [1]Many studies looking at evolution and gene transfer have been conducted and it is highly probable that LUCA was prokaryotic, used DNA as it’s hereditary molecule and lived about 3.9 billion years ago. This common ancestor is why all modern cells share the core features listed in Section 1.1.

For the next 2.1 billion years, prokaryotes were alone on this planet. During this time, most of the biochemistry present in all forms of modern life likely evolved, including mechanisms of DNA replication, the genetic code (how the information in DNA is used to make proteins), and mechanisms of protein synthesis via transcription and translation. In addition, several types of metabolism evolved, including the ability to use sugars as an energy source via aerobic (oxygen-dependent) and anaerobic (in the absence of oxygen) pathways, and the ability to synthesize sugars using light energy via photosynthesis. While eukaryotes (the focus of our next chapter section) evolved many unique structures compared to prokaryotes, much of the biochemistry that our cells use today is the same or very similar to the metabolic processes used by ancient prokaryotes.

- Koonin, E.V. 2009. On the Origin of Cells and Viruses. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1178(1): 47–64. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04992.x. ↵