2 Understanding disabilities

What are disabilities? (3:16)

Que sont les handicaps? (3:26)

Student Voice

These three videos share the stories of three students, including the barriers they face, and what helps make teaching and learning more accessible. When you click on each video, it will open in a new tab.

Mikey (5:00)

Zia (3:04)

Bree (7:04)

Reflect:

- What key messages will you take away from these videos?

- What supports or enablers helped to make learning environments more accessible and inclusive?

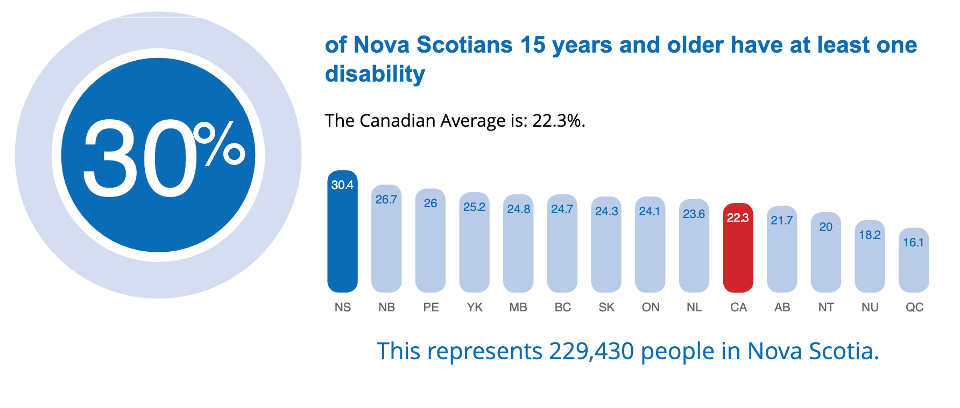

According to the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability, Nova Scotia has a higher percentage of citizens with disabilities than any other province in Canada. 30% of Nova Scotians 15 and older have at least one disability. 21% of youth aged 15 to 24 have at least one disability.

30% of Nova Scotians 15 years and older have at least one disability. Credit: Nova Scotia Accessibility Directorate. Data based on Canadian Survey on Disability, 2017, Statistics Canada. Nova Scotia Accessibility Directorate[1]

Disabilities can be:

- Physical (such as disabilities related to mobility)

- Cognitive

- Sensory (such as hearing or visual)

- Learning

- Intellectual

- Developmental

- Neurological (such as autism or ADHD)

- Mental health related

- Pain related

- Related to chronic health problems

There are many different ways to look at and understand people’s experiences of disability. This list is a starting point.

Disability is vastly diverse, and each person experiences their disability differently.

- The medical model of disability says people are disabled by their impairments or differences. This is an outdated approach, yet it continues to influence how people with disabilities are stereotyped and defined by a condition or by their limitations.

- The social model of disability says people are disabled by the way society, systems, and the built environment are set up.

- In this document, we use the term “persons with disabilities”. Some people with disabilities might prefer the term “disabled people” or use the terms interchangeably.

Scott Jones, disability and queer advocate, shares what this looks and feels like to him

Scott Jones (1:16)

More about disability

- The word “disability” is very broad. It includes persons with a range of disabilities, as well as those who experience barriers to accessibility. People can experience accessibility barriers without having a diagnosed disability. The language we use to talk about disability is imperfect and is always changing. Some people identify differently or prefer different words.

- Not everyone who experiences accessibility barriers identifies as having a disability. This might include Deaf students or students who are neurodivergent (e.g., autistic students or students with ADHD).

- A disability can be permanent, temporary, or episodic. A temporary disability could relate to an injury or bereavement, for example, and an episodic disability could relate to a flareup of a chronic health condition like MS or a bout of depression triggered by situational stress. Many people have more than one disability

- Disabilities can be visible or invisible. A person with a visible disability might use crutches, have a service dog, or wear a hearing aid. An invisible disability, sometimes called a hidden disability, is not obvious. Some examples include depression, learning disabilities, bipolar disorder, or chronic illness. Disabilities like autism, ADHD, or brain injury might be “invisible” at first but become more visible over time.

- Ableism and audism include the practices, attitudes, systems, and structures in a society that privilege people who are considered typical or “normal” — and stigmatize, devalue, or limit the participation, inclusion, and potential of people with disabilities, people who are Deaf or having hearing loss, and neurodivergent people. Ableism and audism can be subtle or obvious, unintentional or intentional, and are often the norm in our society and systems. They rest on the assumption that these persons need to be “fixed” in order to be included or considered successful.[2]

- Accessibility is designing intentionally so persons with disabilities can access, use, and enjoy opportunities, services, devices, physical environments, and information. Accessibility requires conscious planning and effort to make sure something is barrier-free — accessible — to persons with disabilities. Accessibility benefits all of us by making things more usable and practical for everyone, including older people and families with small children.

Barriers to accessibility: Student Voice

These videos share the stories of three students, including the barriers they face, and what helps make teaching and learning more accessible. When you click on each video, it will open in a new tab.

Jenny (2:24)

Charlie (6:25)

Denise (8:13)

Carrie Ann (4:47)

Reflect:

- What key messages will you take away from these videos?

- What supports or enablers helped to make learning environments more accessible and inclusive?

Barriers[3] are anything that prevents a person with a disability from participating fully in school, work, or society. There are many types of barriers. When a disability interacts with a barrier, it can hinder a person’s full and effective participation in education, work, recreation, and social life.

- Attitudinal barriers: How we think about and interact with persons with disabilities. These barriers are based on our beliefs, knowledge, experience and education. For example, assuming that someone who has difficulty speaking also has an intellectual disability, or not interacting socially with someone who has a disability because you feel uncomfortable.

- Physical or architectural barriers: Design elements of a building, such as stairs, doorways, signage, hallway width, and room layout, as well as obstructions and ways of storing items that are needed for work or learning. They also include barriers in outdoor spaces like parks and sidewalks, and how a space is maintained, like snow removal.

- Information or communication barriers: How information is communicated and received and could include small print size, not facing the person when speaking, and not providing information in a variety of formats (written, audio, and video, for example).

- Systemic or organizational barriers: Patterns of behaviour, policies, or practices built into the structure of an organization, that create or perpetuate disadvantage for persons with disabilities. For example, requiring a full course load for eligibility for residences, scholarships, and honours listings.

- Technology barriers: Technology, or the lack of it, can prevent people from accessing information and communication. Common devices like computers, phones, and other tools can all present barriers if they are not set up or designed with accessibility in mind.

- Time, energy, and resource barriers: Needing more time and money to do the same things as a person without a disability. Assistive devices, medications, medical supplies, technology, and physical and psychological therapies are expensive. People with disabilities also often need more time: Time to complete tasks, time to recover between activities, time to rest, and time to take care of their mental and physical health.

- Statistics Canada. (2018). Canadian Survey on Disability, 2017. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/181128/dq181128a-eng.htm ↵

- Bauman, H.L., Simser, S. & Hannan, G. (2013). Beyond ableism and audism: Achieving human rights for deaf and hard of hearing citizens [Presentation]. Canadian Hearing Society Barrier-Free Education Initiatives. https://www.chs.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/beyond_ableism_and_audism_2013july.pdf ↵

- Barriers section adapted from Council of Ontario Universities (2013). Understanding Barriers to Accessibility. https://www.uottawa.ca/respect/sites/www.uottawa.ca.respect/files/accessibility-cou-understanding-barriers-2013-06.pdf ↵

The process of improving the terms of participation in society, particularly for

individuals or groups of individuals who are disadvantaged or under-represented, through enhancing opportunities, access to resources, voice and respect for rights. This creates a sense of belonging, promotes trust, fights exclusion and marginalization and offers the opportunity of upward mobility and results in increased social cohesion.[1]

[1] Nova Scotia Community College Educational Equity Policy