6 Indigenous First Year Experiences in a Time of Reconciliation, Decolonization, and Indigenization

Michelle Pidgeon, Andrea Leveille, Joe Tobin, Donna Dunn, & Mindy Ghag

Introduction

Gilbert, Chapmen, Dietsche, Grayson, and Gardner (1997) provided foundational research that explored first-year experience programming in Canada. However, within their report, there was very little attention given to Indigenous student experience, which was then referred to as Aboriginal/Native student experiences. This is not surprising given the time period of the late 1990s, when most public post-secondary institutions were just beginning to see the importance of supporting Indigenous students in their transition into and through their first year. First Nations, Métis, and Inuit enrolment and graduation rates in the 1990s were low compared to their non-Indigenous peers. This chapter is an opportunity to explore what has occurred since the 1990s for Indigenous student experience, particularly for Indigenous First Year Experience (FYE) programming and services within the broader context of Reconciliation, Decolonization, and Indigenization (RDI) and Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI). Furthermore, with this retrospective view, the evolution and expansion of Indigenous Student Services becomes an important story to share from their beginnings as culturally relevant student support services, to being a key stakeholder that supports institutional development related to RDI.

In terms of a guide, this chapter interweaves the literature on Indigenous student experience, particularly FYE since 1997, to deepen the understanding of Indigenous student success from Indigenous perspectives. We use the Indigenous Wholistic Framework (IWF) (Pidgeon, 2008, 2016) to connect Indigenous FYE to the Indigenous student experience literature to further articulate the need for understanding the whole student. Building on this research and theoretical foundation, the next section looks at the diverse identities and experiences of Indigenous students. This examination helps us better understand how programming can address their specific needs, both as they enter higher education and throughout their academic journey. The results of the First Year Experience Survey (see Chapter 2) and the Pathway study (Pidgeon, et al., 2019), specifically, the data pertaining to first-year initiatives offered by Canadian public English and French universities and colleges, provide a contemporary national picture of the breadth and depth of Indigenous first-year programming and initiatives. The IWF again becomes a helpful demonstration of how such programs and services aim to wholistically support Indigenous student success. We conclude with reflections from the last 25 years and consider what is needed to support the next 7 generations (as per Haudenosaunee/Six Nations philosophy) of Indigenous first-year students in Canadian higher education.

Since 1997: Indigenous Student Success & First Year Experience

There have been many advances in the recruitment and retention of post-secondary Indigenous students since 1997. While the first Indigenous Student Services offices (then called Native Student Centres) were created in the late 1960s at the University of Calgary and the University of Alberta, many of the supports Indigenous student services have in place today were only established in the mid-to-late 1990s in many Canadian universities and colleges (Pidgeon, 2005, 2016a). Consequently, when Gilbert et al. (1997) were doing their FYE research, it made sense that there was little mention of specific Indigenous programming and services. In 2001 less than 50% of Canadian universities had some form of Indigenous student services (Pidgeon, 2016a). By 2024, the absence of such services is rare with over 96% of Canadian universities and colleges now operating some form of Indigenous student support and programming (Pidgeon et al., 2020). Indigenous Student Services in Canada and elsewhere have been a critical home away from home for Indigenous students by providing culturally relevant supports and services that meet the full needs of the student (e.g., emotional, cultural, physical, and intellectual) (Cunningham, 2022; Rossingh & Dunbar, 2012; Tachine et al., 2017; Waterman et al., 2018; Windchief et al., 2018; Windchief & Joseph, 2015).

Indigenous Student Service Centres are seen as Indigenous spaces on campus (Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Tachine et al., 2017; Windchief & Joseph, 2015), whereby “the accommodation of cultural practices and belief […] [is] such that the students could include Indigenous common sense (the mind, body, and spirit) in their educational process” (Windchief & Joseph, 2015, p. 275). This centrality of Indigenous ways of being and doing has created a sense of refuge for many Indigenous students, who feel safer being themselves in these centres. Yet with more demands being placed on Indigenous Student Services units to respond to broader institutional agendas of equity, diversity, inclusion or decolonization, indigenization, and reconciliation, it is important to be mindful that these centres cannot be “a panacea for all Native issues on campus” (Tachine et al., 2017, p. 802), nor can Indigenous staff be the only ones responsible for supporting Indigenous students. We speak more about this later in this chapter.

Figure 1

Indigenous Wholistic Framework

The Indigenous Wholistic Framework (IWF) is a useful theoretical framing of the Indigenous student experience as it considers the whole person, whose emotional, cultural, intellectual, and physical needs are interrelated (Pidgeon, 2008, 2018). As shown in Figure 1, the IWF also provides insights into the importance of relationships within Indigenous communities. For example, think of an Indigenous student being connected to their families, peers, and extended networks of supports within their respective communities. Having the opportunity to build and support such networks within their post-secondary education is an important component of building retention and persistence (Shotton et al., 2013; Walton et al., 2020; Waterman & Lindley, 2013; Windchief & Joseph, 2015). The IWF also recognizes how the Indigenous student is part of the broader relationships Indigenous Nations have with the provincial and federal governments in Canada. These government-to-government-to-government relationships matter within this discussion as we consider the policy implications of post-secondary funding and Indigenous education, particularly those for first-year students. The IWF provides us with an interconnected understanding of Indigenous student experience and success that is wholistic and encompassing of the relationships that are so vital in supporting their education, career, and life dreams (Pidgeon, 2008, 2016a; Walton et al., 2020).

Indigenous student success has been discussed within the literature as coming from a deficit discourse, which attributes fault to the student for their failure; Indigenous scholars argue we should be considering a wholistic or structural understanding of the barriers that might impede Indigenous success across educational sectors (Battiste, 2013; Hogarth, 2017; Lowe & Weuffen, 2023; McLean, 2016; O’Shea et al., 2016). For example, the Saskatchewan Institute of Applied Science and Technology’s 1993 study suggested that

non-completers were more likely to be disabled or married families of Aboriginal ancestry with dependent children. They were more frequently employed and worked more hours. They had lower educational achievement, were less certain about their career choices and were lower in educational commitment. (cited by Gilbert et al., 1997, p. 26)

While the description may be accurate for that period of research – what we now recognize is that Indigenous educational outcomes are negatively and directly impacted by systemic barriers in education (e.g., residential schools, academic tracking, institutional biases) and society (e.g., anti-Indigenous racism) (Association of Canadian Deans of Education, 2009; Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [TRC], 2015).

Asking “what does it mean to be successful in post-secondary education for Indigenous students?” should remind us to pause and consider who is defining success. From a Western institutional perspective, success is often defined as the completion of an undergraduate degree or college diploma within a particular time limit. Academic success may also be tied to GPA and serve as a gatekeeper for scholarships, awards, and entry into graduate school. When thinking from an Indigenous perspective, students often refer to success as giving back to their communities, being a role model for others and having a good life (which is often inclusive of having good pay, a career, etc.) (Andersen et al., 2008; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Mathew et al., 2023; Pidgeon, 2008; Toulouse, 2013). Individual success does not reflect the reasons why many Indigenous people choose to pursue post-secondary education – their motivation extends well beyond their individual gains. Instead, we see Indigenous student success holistically, considering how their emotional, cultural, physical, and intellectual needs are met. For example, attending to the cultural and emotional realms would consider how students’ indigeneity and ways of knowing and being are honoured, valued, and respected within their post-secondary journey. The intellectual and physical realms may look at how the programs, supports, and campus environment are respectful of and relevant to Indigenous peoples. Wholistic success for Indigenous students considers how each aspect of their student experience impacts their perceptions on whether or not their educational journey was a success – this includes inside and outside the classroom, campus culture, and broader community connections.

The research literature is consistent when identifying the barriers to Indigenous students’ holistic success. These include isolation and familial separation, including disconnection and separation from cultural traditions and practices (Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Singson et al., 2016; Windchief et al., 2018); and lack of family support (e.g., perceived as betraying community/family for pursuing western education) (Guillory & Wolverton, 2008). Indigenous students also report feeling marginalized on campus and report anti-Indigenous racism and racialized encounters (Tachine et al., 2017; Windchief et al., 2018). Furthermore, Indigenous students note that their K-12 experience, particularly when on-reserve, did not prepare them adequately for post-secondary education (Day & Nolde, 2009; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Hull, 2009). Housing was noted as a common barrier experienced by Indigenous students, including the high cost of rent in urban centres, lack of space for families, and landlord discrimination (Archibald et al., 2004; Ecklund & Terrance, 2013; Pidgeon & Rogerson, 2017; Singson et al., 2016). A lack of knowledge and understanding of the financial resources meant that Indigenous students were often unaware of (and thus did not take advantage of) the financial aid, scholarships, or other types of financial assistance available to them (Day & Nolde, 2009; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Windchief & Joseph, 2015). Barriers continue to impact Indigenous students’ overall well-being and desire to continue with their education. These barriers may become the hidden curriculum that teaches and reinforces internalized deficit thinking (e.g., biases, assumptions, racist beliefs) about Indigenous students (Margolis, 2001; Shotton et al., 2013).

The research that explored the experiences of Indigenous students who were also parents, found this cohort faced additional unique challenges that most institutions are not in a position to mitigate (e.g., inadequate childcare, relocation of children to new schools which may be hostile/unwelcoming; lack of finances to support their families) (Cox & Pidgeon, 2022; Day & Nolde, 2009; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008). As many Indigenous students have children, balancing their parental and student responsibilities can be a challenge to their continued studies (Cox & Pidgeon, 2022; Day & Nolde, 2009; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008). Indeed, some students will choose their family and/or cultural responsibilities over their studies, requiring them to take breaks or drop out entirely. Consequently, to shift institutional mindsets and practices, an opportunity arises to change those barriers into wholistic supports for Indigenous student success.

Centering a strength-based wholistic approach allows us to see the interconnected relationships that support Indigenous students’ ability to thrive in post-secondary education and place their needs within the physical, emotional, intellectual, and cultural realms in balance (Pidgeon, 2008; Walton et al., 2020). The IWF model then provides a way for student services, faculty, and administration to consider their roles and responsibilities in wholistically supporting Indigenous student success in ways that identify and remove institutional and/or systemic barriers (Pidgeon, 2008; 2016b).

Interconnected relationships demonstrate the importance of Indigenous students’ family and other supportive relationships and kinship systems to their success, which extends to the university community (Cox & Pidgeon, 2022; Day & Nolde, 2009; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; HeavyRunner & DeCelles, 2002; HeavyRunner & Marshall, 2003; Walton et al., 2020; Windchief et al., 2018). Connected to relationships, social support is also important to their success. Indigenous students attributed connections with peers and faculty members, including non-Indigenous peoples, as supporting their education journey (Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Rossingh & Dunbar, 2012; Windchief et al., 2018). Including family members in on-campus activities, particularly for those Indigenous students with children, supports family connection and mitigates financial burdens (e.g., free food at events inclusive of families) (Cox & Pidgeon, 2022; Windchief et al., 2018). Day and Nolde (2009) shared that one of their participants who was a single mother and facing additional barriers and responsibilities, found motivation in that she was doing all this hard work for not just her, but her children. The value of interconnected relationships within many Indigenous Nations is demonstrated when there is a family connection to an institution – for example, having other immediate or extended members attend an institution and relate their experiences as positive means that others are more likely to trust that the institution is safe and understands Indigenous students (Day & Nolde, 2009; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Tachine et al., 2017). As Guillory and Wolverton (2008) found in their study with American Indian/Alaska Natives, “education passed down from one generation to another served as a persistence factor” (p .74).

Furthermore, creating spaces on campus, where Indigenous students find culturally relevant supports and kinship through Indigenous student services further extends those relationships of support (Day & Nolde, 2009; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Rossingh & Dunbar, 2012; Tachine et al., 2017; Windchief et al., 2018). Indigenous spaces on campus, whether student clubs or Indigenous student services, provide cultural affirmation which may not be experienced anywhere else on campus (Day & Nolde, 2009; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Rossingh & Dunbar, 2012; Tachine et al., 2017; Windchief et al., 2018). For example, the Australian Centre for Indigenous Knowledges and Education (ACIKE) provides “personalized academic support and advice at a course-focused level including mentoring and tutoring, study planning, and customized skill development workshops” [while also offering] “a culturally safe and empowering environment that enables reflection on Indigenous history and diversity” (Rossingh & Dunbar, 2012, p. 63). This Centre’s programming and wrap-around supports exemplify how cultural affirmation can support the academic journeys of Indigenous students and models how the IWF might be applied in practice. The work of ACIKE resembles the kinds of programming and supports offered throughout Indigenous Student Services Centres across Canada.

Continuing to think wholistically, addressing student needs within the physical realm such as adequate financial support (including expanding financial supports for single parents) (Cox & Pidgeon, 2022; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Windchief et al., 2018), childcare, and housing remain vitally important to Indigenous student persistence (Archibald et al., 2004; Ecklund & Terrance, 2013; Pidgeon & Rogerson, 2017; Singson et al., 2016). Additionally, programs including academic preparation, summer bridging, and orientation help to support the intellectual needs of Indigenous students (Day & Nolde, 2009; Guillory & Wolverton, 2008; Rossingh & Dunbar, 2012; Windchief et al., 2018). Such programming and services are vital to the first-year experience, helping the student through a period of transition and adjustment to post-secondary education.

Who are Indigenous Students?

This question requires ongoing reflection and understanding as the demographics of Indigenous populations shift and high school graduation rates increase. However, there are caveats to understanding Indigenous students since it matters where they did their K-12 education, as research continues to demonstrate the inequity between on-reserve and off-reserve school completion rates (Louie & Gereluk, 2021) impacts how well Indigenous students are prepared to enter post-secondary.

Understanding that the diversity of Indigenous K-12 journeys is highly varied and this requires asking reflective questions to wholistically support Indigenous student success. For example, within the K-12 system — how many Indigenous students are being inspired to pursue their hopes and dreams of a future beyond high school? Research literature continues to demonstrate how the K-12 system is not preparing or encouraging Indigenous students toward higher education pathways, this, along with other educational and societal barriers means we are still not seeing the K-12 completion rates that would reach parity with non-Indigenous high school completion rates. Understanding the gaps within the K-12 education system, there is a responsibility for post-secondary institutions to support building relationships with Indigenous communities and the schools that serve these communities (whether on-reserve or off) (Drummond & Rosenbluth, 2013; Porter, 2016; Richards, 2018; Statistics Canada, 2022). Universities and colleges can provide important solutions in relationship with their local school districts and Nations so that Indigenous students are provided the tools and supports to navigate their first year and beyond.

Institutions should know exactly who their entering students are demographically, socio-economically, and in terms of ethnic diversity and prior learning. Tracking systems should be used not simply for research purposes but for practical, applied purposes in order to identify potential early leaves and to develop effective programs and services. (Gilbert et al., 1997, p. 111)

As we consider programs and services for the next 7 generations of Indigenous learners, everyone engaged in that journey from recruitment, admissions, financial aid and awards, housing, academic advising, and faculty need to understand why Indigenous students attend post-secondary education. In deepening their understanding, those working within academic faculties and student affairs and services can help shift broader institutional perceptions, practices, and policies of what success means and what supports are needed for these students to attain their dreams. Students giving back to their Indigenous community or Nation is an important persistence factor identified throughout the literature (Shotton et al., 2013; Walton et al., 2020; Waterman & Lindley, 2013; Windchief & Joseph, 2015). Indigenous students are “[m]aking a better life for their families. It reflects an Indigenous philosophy of putting community before individualism” (Guillory & Wolverton, 2008, p. 74), which challenges the individual gain discourse dominant across Western higher education (and society). Understanding such motivation connects to the broader retention literature on factors that support and hinder Indigenous student persistence (CHiXapkaid (Dr. D. Michael Pavel), 2013; HeavyRunner & DeCelles, 2002; Pavel, 1999; Walton et al., 2020).

Within Canada, we are seeing a shift in Indigenous student demographics. Between the 1970s and 1990s, many students were older-than-average, female, and/or parents who chose to return to school later in life (Stonechild, 2006). This group is still a substantial portion of the Indigenous student population, particularly at the graduate level. Since the 1990s, there has been significant growth in direct entry from high school, college transfer students, and Indigenous students who are former youth in care (Layton, 2023). Layton observed that extending the age range to 46 to measure high school and post-secondary completion demonstrated a higher completion rate, it just took them more time. Layton’s findings make sense given the number of Indigenous students who are also parents, may live remotely, work while studying, and/or are engaged in language and cultural work in their home communities. Despite advances in high school completion (albeit on-reserve First Nations have lower completion rates than off-reserve First Nations (Layton, 2024)) there remain gaps in educational parity between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous Canadians (as shown in Figure 2).

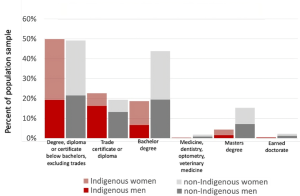

Figure 2

Post-secondary attainment Indigenous compared to non-Indigenous Canadians

Note: Data in this chart is from the Statistics Canada 2022 data table

When we look at degree completion, Figure 2 shows how non-Indigenous people are much more likely to attain an advanced degree such as a BA, MA, or PhD compared to Indigenous people (over three times more likely). Gender differences within the Indigenous population are also visible with men being 2.5 times more likely to go into trades compared to Indigenous women, and Indigenous women are 2 times more likely to get a university degree (e.g. BA or higher) compared to Indigenous men. Comparing the two previous Canadian censuses (2016, 2022), Statistics Canada demonstrates that while high school completion gaps are narrowing between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, the gaps of post-secondary completion are widening (e.g., 12.9% of Indigenous compared to 27.8% of non-Indigenous Canadians completed a bachelor’s degree or higher). There are also gaps between First Nations (11.3%), Métis (15.7%), and Inuit (6.2%) who have a bachelor’s degree or higher (Statistics Canada, 2023).

The diversity of Indigenous students encompasses a multitude of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples with varying levels of connection to their languages, cultures, and homelands. Such linguistic and cultural diversity means there is no way to create a homogenous representation of the Indigenous student. The impact of colonization through residential schools, the ‘60s scoop, and other assimilationist policies which attempted to eradicate Indigenous peoples have negatively impacted many Indigenous families and their connection to who they are as Indigenous peoples (Paquette & Fallon, 2010; Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996; TRC, 2015). These policies connect directly to how, if, and why an Indigenous person may (or may not) choose to self-identify, whether they feel safe in various institutional spaces, and how they wish to present themselves as Indigenous peoples in post-secondary education. Each Indigenous student is unique – and that uniqueness needs to be understood and honoured as they choose their post-secondary journey, particularly how institutions may respond to supporting their FYE from policy, programs, and practices.

From Policy, Programs, and Practices

Understanding the importance of supporting students into higher education means that Indigenous FYE programming should consider the various types of programs and services offered to Indigenous students as they enter the institution and transition through their first year. As Gilbert et al., (1997) acknowledged “there is no one way, or even one best way, of doing the First-Year Experience. There is no panacea. There is no quick fix” (p.3). There is more truth in Gilbert et al.’s statement now than there ever was since the diversity of Indigenous students across Canadian universities and colleges requires place-based, culturally-informed approaches that should look different at every institution.

Within the First Year Experience Survey conducted by Smith, Daniels, and Brophy (2023, see Chapter 2) specific questions were asked regarding their provision of specific FYE services/supports for Indigenous students. Of the 51 institutions responding to this survey, 33 indicated they provide some specific FYE programming for Indigenous students (~65%) In addition to these survey results, we draw from the Pathways study relevant first-year programs and services available to Indigenous students attending public, English or French, universities and colleges. Specifically, the Pathways study identified 36 (out of 74) universities offered 72 first-year programs for Indigenous students while 41 colleges (out of 156) offered 64 unique programs that may include (but are not limited to) summer camps, orientation week, workshops, academic bridging programs, short term to full-year support programs (Pidgeon et al., 2020). These two datasets provide insight into the nature of programs and services available for Indigenous students since 1997.

While the Smith et al. (2023) study was a confidential survey, the data gathered by Pidgeon et al. (2020) was based on publicly available information through institutional websites. Therefore, we are not able to make direct links between the two data sets (e.g., which institutions participated in the survey and whose websites were examined). The analysis of these datasets also provides insights into strengths and potential areas of growth for supporting Indigenous student success, along with the importance of culturally appropriate data collection/databases for understanding Indigenous student experiences throughout their educational journey. Each of these datasets aimed to gather information about the nature of programs and services for Indigenous students, particularly focusing on the first-year experience.

Who Oversees Indigenous FYE Programming?

The oversight, staffing, and resources associated with first-year initiatives specifically for Indigenous students have expanded greatly since 1997. Predominately, FYE initiatives fall to the Indigenous Student Services unit- which demonstrates an expansion of their services and supports. Within the FYE Survey – 14 out of the 33 programs were directly overseen by the Indigenous Student Services, while 5 were overseen in partnership between Student Services and an Indigenous Advisor. Other survey participants indicated that their programs were within the responsibilities of their VP Indigenous or Indigenous Strategy (n=3). There were a few instances where responsibility fell to units, such as the Office of Human Rights and Equity or Student Life & Intercultural (n=2) (Smith et al., 2023).

Within the Pathways study, many of the access and First-Year Experience programs were offered by (or in partnership with) Indigenous Student Services. Some first-year supports were offered at the faculty level. Faculty-based programs were aimed at Indigenous students entering into their specific disciplines; typically, these programs were academic bridging and support programs. For example, the University of Saskatchewan has four such faculty-based programs (e.g., Engineering, Nursing, Arts & Social Sciences, and Law). The University of Saskatchewan offered an Indigenous Summer Access Program during the last week of August, for those students enrolled in the Arts and Sciences bridging program to help support their transition to first year. Programs offered by student affairs units were typically open to all Indigenous undergraduate students. As an example, the University of Waterloo offered an Academic Transition Opportunities (ATO) program for Indigenous undergraduate students which was a partnership between different student services units. Students applying to this program are then offered a variety of supports (e.g., orientation workshops, academic counselling with an Indigenous student advisor, tutors, Elders and Cultural counsellor supports and programming, and work-study opportunities). Mount Allison University, through its Indigenous Student Services, offered an Indigenous Mentorship Program that paired first-year students with upper-level Indigenous students or allies.

The fact that Indigenous-specific programming often falls to Indigenous student services professionals is important to acknowledge as there is an associated cost both personally and professionally for Indigenous staff. In this era of decolonization and reconciliation, there is a tangible cultural taxation on Indigenous students (and staff) who are burdened with the responsibility to educate others about Indigenous peoples, cultures, issues, and histories. Often finding themselves as the sole Indigenous person in a classroom or meeting the burden to speak for all Indigenous issues or matters is a reality experienced by many Indigenous students and staff, leading to burnout and withdrawal or resignation (Cunningham, 2022; Tachine et al., 2017). Many Indigenous staff come to their position within the university wanting to support Indigenous students as they navigate through colonial institutions and see it as their responsibility to give back to their extended Indigenous community (Oxendine et al., 2018). This results in a cultural taxation on Indigenous people – staff and students alike – that has them over-extended and forced to buffer others from the lateral violence, and anti-Indigenous racism, while also being the source of all knowledge for their non-Indigenous colleagues and peers (Cunningham, 2022; Henry, 2017; Mistretta & DuBois, 2021; Oxendine et al., 2018; Tachine et al., 2017).

When is the Program Provided?

Considering the needs of Indigenous students should be first and foremost when providing support and the timing of those supports is crucial. The FYE Survey and the Pathways project identified several time frames in which FYE programming is offered (e.g., summer, week before classes, first week of classes, first term, second term). For example, 13 survey participants indicated they did a combination of programming that started in the summer and continued through to the second semester (Smith et al., 2023). While some programs begin the week before the semester to help introduce students to the campus early before the influx of other first-years and returning students (n=7). In comparison, other institutions waited and only offered programming during the first week of classes (n=5). Fewer institutions offered programming in the summer plus the week before the start of the first term (n=3), the first two semesters (n=3), or only in the summer (n=1), or summer plus first term (n=1) (Smith, et al., 2023).

From the Pathways study, we can draw on specific examples of the timing of program delivery identified by Smith et al. (2023). For example, the Pathways study found academic bridging programs were typically two semesters in length (e.g., First Nations’ Transition Program at the University of Lethbridge) whilst first-year programming was typically for the full year (e.g., Indigenous Student Access Pathway at Dalhousie University) (Pidgeon, et al, 2019). In a few cases, programming was open to those in first and second year (e.g., Aboriginal Student Achievement Program at the University of Saskatchewan). The timing of these programs is pertinent to considering when and how Indigenous students need supports. Those offered before the start of the semester provide time to adjust to the campus and build new relationships, yet as previous discussions of the literature attest – year-long programming with wholistic supports provides dependability and sustainable connections for Indigenous students.

Evaluating Program and Student Experience

There is an understandable resistance to evaluation by Indigenous peoples which is partly due to colonial and systemic biases that have continued to misrepresent and misunderstand Indigenous peoples. Furthermore, the high frequency of surveys of Indigenous communities, especially students, is creating survey fatigue, particularly when they do not see the results and more importantly, feel the impact of sharing their experiences on teaching, programs, services, and/or policies (Field, 2020; Walter & Andersen, 2016). Yet, it is increasingly being recognized that Indigenous-specific data is vitally important to supporting Indigenous programming and support services (Shotton et al., 2013; Walter & Andersen, 2016). Additionally, external and internal accountability measures require more evidence-based data to support program development, change, and funding. Given that many Indigenous programs are externally funded through short-term grants or donations – it is prudent to connect the importance of understanding Indigenous student experiences to their learning aspirations alongside the program goals and objectives. This ultimately may determine whether or not funding, and importantly staff positions tied to these programs, continue.

Smith et al. (2023) asked their FYE participants whether or not they measured outcomes/assessment – 17 of 32 indicated they did, while another 8 were unsure and 7 indicated they did not measure outcomes. Of those 17 who did look at program outcomes, they collected this data in a variety of ways. Some only used surveys (n=7), while others (n=6) used surveys plus some form of oral feedback (e.g., debriefs, focus groups, ongoing discussions with students). Some indicated they only used one of the following methods: attendance (n=1) or debrief (n=2) (Smith et al., 2023).

Assessment practices were not always obvious on institutional websites. However, during the interviews for the Pathways project, participants noted that existing program assessments did not include questions or criteria about how the program could equip Indigenous students with skills and abilities to contribute to and support their communities. There was also a deficiency identified by participants in the scarcity of pre-assessments of student readiness to undertake a program. Participants felt that the lack of such assessments set the student up for difficulty. If such assessments did exist, students could be appropriately matched to a bridging course or other supports to aid in their positive transition to university.

One of the ongoing challenges is the apathy (and sometimes outright resistance) toward ongoing evaluation of programs and services for Indigenous students. Some of this resistance is due to a lack of adequate resources and knowledge (both human and financial) to support implementing a culturally relevant evaluation process. There is also a resistance to the perception of the allocation of resources versus the percentage of Indigenous students served (e.g., there are so few resources, is it worth investing in evaluating services for less than 3% of the student population?). Yet those within Indigenous Student Services are often asked to demonstrate their impact and reach to students – in some cases experiencing hyper-surveillance (or micro-management) compared to other units and are asked to constantly justify their resource and staffing allocation. The negative consequences of apathy and ongoing systemic racism are that program delivery does not improve and professional practices do not change. Furthermore, in the absence of impact data and stories, Indigenous programs and staff positions can be put in precarious situations, particularly when these programs or staff are externally funded. Culturally informed assessment methods and processes can be developed which support program learning outcomes, understand the student experience, and address potential institutional reporting needs (e.g., for funders, academic strategic plans, justification for permanent positions, program adjustment to respond to changing student needs etc.).

Retention Rates

From the FYE survey, 6 out of the 32 respondents indicated they collected data related to retention rates. A limitation of this survey data is that it was unclear how institutions were defining retention and/or collecting this data. Another 13 were unsure if such data was collected and the remaining 13 said they did not collect this data (Smith et al., 2023). The Pathways study did not include retention data or information as it was not something that was publicly shared via institutional websites (Pidgeon et al., 2020).

Research literature continues to show that Indigenous students are frequently underrepresented in institutional data. This discrepancy can be attributed to several factors, including inadequate self-identification processes and ambiguous enrolment numbers. Consequently, accurately determining Indigenous students’ participation or graduation rates poses a significant challenge (McKeown et al., 2018; Shotton et al., 2013; Uink et al., 2019). Additionally, given that Indigenous students represent approximately 3-5% of the general student population it often means their data is not disaggregated from other students and may not be included in broader retention reports or other institutional reports. Therefore, more work is needed to support culturally relevant data (Walter & Andersen, 2016) and reporting of Indigenous student participation, withdrawal, and persistence rates.

Policies that Support Access and FYE

The Indigenous student experience from recruitment to admission through their first year on to graduation has direct policy implications which ultimately informs programs and practices. From the Pathways project, several examples across the country illustrate how flexible admissions policies can be used to support access to post-secondary for Indigenous students. For example, there were 30 university and 61 college-level bridging programs which had classes and skills training to prepare a new student for post-secondary life. The College of the North Atlantic for example had a program open to mature students who did not meet the adult basic education requirements, and through this program, they had a year of upgrading enhanced by the inclusion of community Elders and knowledge holders. Nipissing University had a program that partnered with local Nations to allow some of the courses to be taken in-community while still counting as credit towards a degree. A few institutions referred to the Jay Treaty for fee scheduling and admissions applicability. For example, Vancouver Island University and the University of Saskatchewan mentioned the Jay Treaty as part of their Indigenous admissions. Other institutions, like Douglas College and Algonquin College, simply required U.S. Indigenous people to provide a status card, tribal enrollment documentation, or tribal registration in the admissions process.

While many universities had flexible admissions for Indigenous learners, college programs were the most innovative with 16 programs offering personalized custom assessment. Northern Lakes College for example had agreements for local youth to take bridging programs based on interviews looking at honesty, respect, adaptability, and other aspects of good citizenry. Mohawk College offered those who had a positive assessment from an intake interview with the Indigenous Student Services team, an exemption from competitive GPA requirements for post-secondary programs, minimum program requirements still applied. Admissions policies are also connected to scholarship and housing policies (e.g., third-party billing, self-identification policies) further demonstrating the importance of policy to wholistically support students. Specific admissions policies for Indigenous students also informed referrals to resources (e.g., Indigenous Student Services, Indigenous student clubs and societies) and academic programs that would support their transition (e.g., summer camps, bridging programs). As earlier examples demonstrated, the absence of such policies and programs does create systemic barriers to Indigenous students’ wholistic success.

Supporting Indigenous Students Transition to and Through First Year

Thinking of the next 7 generations of Indigenous students coming to post-secondary education, it is a hope that the work of today on Reconciliation, Decolonization, and Indigenization (RDI) along with Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) does inspire significant changes to the educational system. As we reflect upon how to better support Indigenous students into and through their first year it is important that the educational outcomes of Indigenous students are reflective of their experiences. Educational outcomes matter, if “the goal of increasing overall rates of student success and retention” matters (Gilbert et al., 1997, p.26). Gilbert et al. (1997) concluded their report with policy recommendations that would support First Year Experiences, with one in particular standing out: “An emphasis on holistic student growth and development in the first year works better than a narrow or exclusive emphasis on technical academic expertise and specialization” (p. 111). We agree that understanding the whole student and their relationships is vital when studying first year experiences of Indigenous students.

In reviewing both the literature and current programs and practices, it is evident that many post-secondary institutions in Canada have moved forward in wholistically supporting the Indigenous student experience. Yet, it is also clear that such programming is often precarious due to being externally funded, supervised by contractual staff (vs permanent positions), and without a sustainability plan to continue providing programs and services which support Indigenous student experience. Once the external (or short-term) funds disappear, the initiative and staffing that supported the students often follow suit. Consequently, the work of RDI and EDI requires an intentional institutional commitment of resources- both financial and human to support staffing and programming needs that are not competing for said resources. Such institutional commitments would mean that Indigenous-specific programs and services have the stability required to sustain relationships and trust for supporting Indigenous students. Institutions also have the responsibility to understand the burden and pressures of walking in both worlds experienced by Indigenous students, staff, and leaders in the work of EDI and RDI. Indigenous peoples are navigating and challenging Western institutions while also reclaiming, revitalizing, and honouring their Indigeneity within and outside these spaces. Understanding the costs of cultural taxation means that appropriate actions can be taken to alleviate those burdens and costs to better support RDI and EDI without it being solely placed upon Indigenous peoples. Specific to FYE experiences, the wholistic needs of Indigenous students and staff involved in program design and implementation require ongoing supports for their well-being, cultural thriving, and empowerment.

References

Andersen, C., Bunda, T., & Walter, M. (2008). Indigenous higher education: The role of universities in releasing the potential. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 37(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1326011100016033

Archibald, J., Pidgeon, M., Hare, J., van der Woerd, K., Janvier, S., & Sam, C. (2004). The role of housing in Aboriginal student success: Post-secondary institutions in Vancouver. Canada Mortgage & Housing Corporation.

Association of Canadian Deans of Education (ACDE). (2009). Accord for Indigenous Education. http://www.csse scee.ca/docs/acde/acde_accord_indigenousresearch_en.pdf

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Purich.

CHiXapkaid (Dr. D. Michael Pavel). (2013). First-year experience for Native American freshman. In H. Shotton, S. C. Lowe, & S. J. Waterman (Eds.), Beyond the asterisk: Understanding Native students in higher education (pp. 125–138). Stylus.

Cox, R. D., & Pidgeon, M. (2022). Resisting colonisation: Indigenous student-parents’ experiences of higher education. In G. Hook, M-P., Moureau, & R. Brooks (Eds), Student Carers in Education (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 88–105). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003177104-7

Cunningham, S. (2022). Stories from inside the circle: Embodied Indigenity and resurgent practice in post-secondary institutions. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Calgary]. https://prism.ucalgary.ca/items/b46c3407-93bb-4cf3-ab74-a89ebf9499b0

Day, D., & Nolde, R. (2009). Arresting the decline in Australian Indigenous representation at university. Equal Opportunities International, 28(2), 135–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610150910937899

Drummond, D., & Rosenbluth, E. K. (2013). The debate on First Nations education funding. https://canadacommons.ca/artifacts/1184096/the-debate-on-first-nations-education-funding/1737217/

Ecklund, T., & Terrance, D. (2013). Extending the rafters: Cultural context for Native American students. In H. Shotton, S. C. Lowe, & S. J. Waterman (Eds.), Beyond the asterisk: Understanding Native students in higher education (pp. 53–66). Stylus.

Field, A. (2020). Survey fatigue and the tragedy of the commons: Are we undermining our evaluation practice? Evaluation Matters—He Take Tō Te Aromatawai, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.18296/em.0054

Gilbert, S., Chapman, J., Dietsche, P., Grayson, P., & Gardner, J. (1997). From best intentions to best practices: The first-year experience in Canadian postsecondary education. (Monograph Series Number 22). National Resource Centre for the Freshman First Year Experience and Students in Transition.

Guillory, R. M., & Wolverton, M. (2008). It’s about family: Native American student persistence in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 79(1), 58–87. https://www-tandfonline-com.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/doi/pdf/10.1080/00221546.2008.11772086?needAccess=true

HeavyRunner, I., & DeCelles, R. (2002). Family education model: Meeting the student retention challenge. Journal of American Indian Education, 41(2), 29–37.

HeavyRunner, I., & Marshall, K. (2003). Miracle survivors: Promoting resilience in Indian students. Tribal College Journal, 14(4), 14–18.

Henry, F. (2017). The equity myth: Racialization and Indigeneity at Canadian universities. UBC Press. http://books.scholarsportal.info/viewdoc.html?id=/ebooks/ebooks3/upress/2017-07-24/1/9780774834902

Hogarth, M. (2017). Speaking back to the deficit discourses: A theoretical and methodological approach. Australian Educational Researcher, 44(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0228-9

Hull, J. (2009). Post-secondary completion rates among on-reserve students: Results of a follow-up survey. Canadian Issues, Winter (Journal Article), 59–64. https://www.proquest.com/openview/1bfedc64d3d7beaa08538494e7730881/1?cbl=43874&pq-origsite=gscholar&parentSessionId=9v5ChbUhJg9dQZcopiTTynMs2X%2B%2Fq5fBQnZH8wcr5S4%3D

Layton, J. (2023). First Nations youth: Experiences and outcomes in secondary and postsecondary learning. Statistics Canada = Statistique Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-599-x/81-599-x2023001-eng.htm

Louie, D. W., & Gereluk, D. (2021). The insufficiency of high school completion rates to redress educational inequities among Indigenous students. Philosophical Inquiry in Education, 28(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.7202/1079433ar

Lowe, K., & Weuffen, S. (2023). “You get to ‘feel’ your culture”: Aboriginal students speaking back to deficit discourses in Australian schooling. Australian Educational Researcher, 50(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00598-1

Margolis, E. (Ed.). (2001). The hidden curriculum in higher education. Routledge.

Mathew, D., Nishikawara, R., Ferguson, A., & Borgen, W. (2023). Cultural infusions and shifting sands: What helps and hinders career decision-making of Indigenous young people. Canadian Journal of Career Development, 22(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.53379/cjcd.2023.345

McKeown, S., Vedan, A., Mack, K., Jacknife, S., & Tolmie, C. (2018). Indigenous educational pathways: Access, mobility, and persistence in the BC post-secondary system (p. 39). BCCAT. http://www.bccat.ca/pubs/Indigenous_Pathways.pdf

McLean, S. (2016). From cultural deprivation to individual deficits: A genealogy of deficiency in Inuit adult education. Canadian Journal of Education, 39(4), 1–28. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1122009.pdf

Mistretta, M. A., & DuBois, A. L. (2021). Burnout and compassion fatigue in Student Affairs In M. Sallee (Eds), Creating sustainable careers in Student Affairs (1st ed., pp. 140–158). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003443834-10

O’Shea, S., Lysaght, P., Roberts, J., & Harwood, V. (2016). Shifting the blame in higher education—Social inclusion and deficit discourses. Higher Education Research and Development, 35(2), 322–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1087388

Oxendine, S. D., Taub, D. J., & Oxendine, D. R. (2018). Pathways into the profession: Native Americans in student affairs. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 55(4), 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2018.1470005

Paquette, J., & Fallon, G. (2010). First Nations education policy in Canada: Progress or gridlock? University of Toronto Press.

Pavel, D. M. (1999). American Indians and Alaska Natives in higher education: Promoting access and achievement. In K. G. Swisher & J. Tippeconnic (Eds.), Next Steps: Research and practice to advance Indian education (pp. 239–258). ERIC.

Pidgeon, M. (2005). Weaving the story of Aboriginal student services in Canadian universities. Communique, 5(3), 27–29.

Pidgeon, M. (2008). Pushing against the margins: Indigenous theorizing of “success” and retention in higher education. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 10(3), 339–360. https://doi.org/10.2190/CS.10.3.e

Pidgeon, M. (2016a). Aboriginal student success & Aboriginal Student Services. In D. Hardy Cox & C. Strange (Eds.), Serving diverse students in Canadian higher education: Models and practices for success (pp. 25–39). McGill University Press.

Pidgeon, M. (2016b). More than a checklist: Meaningful Indigenous inclusion in higher education. Social Inclusion, 4(1), 77–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.17645/si.v4i1.436

Pidgeon, M. (2018). Moving between theory and practice within an Indigenous research paradigm. Qualitative Research, 1468794118781380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794118781380

Pidgeon, M., & Rogerson, C. (2017). Lessons learned from Aboriginal students’ housing experiences: Supporting Aboriginal student success. Journal of College and University Student Housing, 44(1), 48–73.

Pidgeon, M., Tobin, J., Setah, T., Leveille, A., Dunn, D., Johnson, K., & Bubela, T. (2020). Looking forward… Indigenous pathways to and through Simon Fraser University. Wholistic understandings of access, transition, and persistence (p. 1-241). Simon Fraser University. http://www.sfu.ca/content/dam/sfu/vpacademic/files/PathwaysProject_FinalReport_July2020.pdf

Porter, J. (2016, March 14). First Nations students get 30 per cent less funding than other children, economist says. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/first-nations-education-funding-gap-1.3487822

Richards, J. (2018). Pursuing reconciliation: The case for an off-reserve urban agenda. Commentary – C.D. Howe Institute, 526, 1–25. https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/pursuing-reconciliation-case-reserve-urban-agenda

Rossingh, B., & Dunbar, T. (2012). A participative evaluation model to refine academic support for first year Indigenous higher education students. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 3(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v3i1.113

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. (1996). Gathering of strength, Volume 3. Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP).

Shotton, H., Lowe, S. C., & Waterman, S. J. (Eds.). (2013). Beyond the asterisk: Understanding Native students in higher education. Stylus.

Singson, J. M., Tachine, A. R., Davidson, C. E., & Waterman, S. J. (2016). A second home: Indigenous considerations for campus housing. The Journal of College and University Student Housing, 42(2), 110–125. http://www.nxtbook.com/nxtbooks/acuho/journal_vol42no2/index.php?startid=7

Smith, S., Daniels, A., McEvoy, A., & Brophy, T. (2023). Results of a pan-Canadian FYE and SIT programs survey. CACUSS 2023 Conference, Niagara Falls, ON. https://pheedloop.com/CACUSS2023/site/home/

Statistics Canada. (2022). High school completion by Indigenous identity, Indigenous geography and labour force status: Canada, provinces and territories [dataset]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810042001

Statistics Canada. (2023). An update on the socio-economic gaps between Indigenous peoples and the non-Indigenous population in Canada: Highlights from the 2021 Census. Government of Canada. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1690909773300/1690909797208#chpapp-a-6

Stonechild, B. (2006). The new buffalo: The struggle for Aboriginal post-secondary education in Canada. University of Manitoba Press.

Tachine, A., Cabrera, N., & Yellow Bird, E. (2017). Home away from home: Native American students’ sense of belonging during their first year in college. The Journal of Higher Education, 88(5), 785–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2016.1257322

Toulouse, P. R. (2013). Beyond shadows: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit student success. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Teachers’ Federation = Fédération canadienne des enseignantes et des enseignants.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). (2015). Honoring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. TRC. http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf

Uink, B., Hill, B., Day, A., & Martin, G. (2019). ‘Wings to fly’: A case study of supporting Indigenous student success through a whole-of-university approach. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2019.6

Walter, M., & Andersen, C. (2016). Indigenous statistics: A quantitative research methodology. Routledge.

Walton, P., Hamilton, K., Clark, N., Pidgeon, M., & Arnouse, M. (2020). Indigenous university student persistence: Supports, obstacles, and recommendations. Canadian Journal of Education, 43(5), 430–464. http://cje-rce.ca/journals/volume-43-issue-2/indigenous-university-student-persistence/

Waterman, S. J., & Lindley, L. S. (2013). Cultural strengths to persevere: Native American women in higher education. NASPA Journal About Women in Higher Education, 6(2), 139–165. https://doi.org/10.1515/njawhe-2013-0011

Waterman, S. J., Lowe, S. C., & Shotton, H. J. (Eds.). (2018). Beyond access: Indigenizing programs for Native American student success. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Windchief, S., Arouca, R., & Brown, B. (2018). Developing an Indigenous mentoring program for faculty mentoring American Indian and Alaska Native graduate students in STEM: A qualitative study. Mentoring & Tutoring, 26(5), 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2018.1561001

Windchief, S., & Joseph, D. H. (2015). The act of claiming higher education as Indigenous space: American Indian/Alaska Native examples. Diaspora, Indigenous and Minority Education, 9(4), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2015.1048853