7 2SLGBTQIA+ First Year Programming in Canadian Post-Secondary Institutions: Insights & Future Directions in Research, Policy and Practice

Frederick Ezekiel & Kayla J. Goruk

Introduction

Two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, gender non-binary, queer, intersex, asexual and students with diverse genders or non-heteronormative experiences and/or expressions of sexual orientation (2SLGBTQIA+ students) make significant contributions to the richness of post-secondary communities. Over the past several decades, significant strides have been made toward the inclusion and celebration of 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals within broader societies, stemming from the Stonewall riots and global pride movements. These gains have created greater freedom for youth to explore their sexual orientation and gender identities, allowing them to express themselves authentically and challenge post-secondary leaders to continually create educational environments that support and value the gender and sexual diversity of students.

Often, 2SLGBTQIA+ students have overcome significant adversity prior to attending postsecondary education, grappling with developing and expressing identities that may not have aligned with dominant norms of their social environments, often in the face of direct or indirect forms of hostility and exclusion. 2SLGBTQIA+ students bring immense individual strengths, experiences, and attributes of resilience into the post-secondary landscape, achieving academically while navigating challenges associated with forging identity, often in the face of adversity.

While great strides have been made to create more freedom for expressions of diverse gender identities and sexual orientations, systemic barriers and oppressive cultural norms still drive disparities for 2SLGBTQIA+ students while pursuing post-secondary studies in Canada. From navigating family and interpersonal conflict while coming out, to balancing perceptions and oppressive views within their residence living environments, there are unique and disproportionate challenges that place an elevated ‘minority stress’ burden upon 2SLGBTQIA+ students, which drives disparities in mental health and academic performance. Ultimately, these experiences contribute to 2SLGBTQIA+ students leaving post-secondary studies more frequently during or after their first year, driving disproportionately lower retention rates compared to their non-LGBTQIA+ peers (Gorman & Brennan, 2023).

The unique experiences and needs of 2SLGBTQIA+ students warrant distinctively responsive supports, resources, and spaces for community building to ensure they can fully realize their potential to thrive in post-secondary education and beyond. This chapter will explore: the current landscape specific student supports during transition to university in Canada; unique academic, social and health experiences and outcomes; and promising directions for building transitional supports that will create more equitable educational conditions for 2SLGBTQIA+ students.

Theoretical Approach

Ecological systems theory is a theoretical framework that proposes that people carry their individual characteristics (e.g., age, race, life-stable personality characteristics, abilities, gender, sexual orientation, etc.) with them as they move through the world, and interactions between factors at family, community, institutional (e.g., education system, healthcare), political, and broader system levels interact with individual characteristics to influence human development outcomes (Bronfenbrenner, 2000; Siddiqi, Irwin, & Hertzman, 2007).

Given that 2SLGBTQIA+ students are impacted by their developmental trajectory prior to university, which might include navigating experiences within affirming or hostile family, school, healthcare and community environments, ecological systems theory is an effective framework to guide our understanding of how to support the transition of 2SLGBTQIA+ students into university. Early experiences of 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals influence their psychosocial and personal wellbeing, while also impacting their opportunities for healthy identity development.

Student development theories offer insight into positive and negative drivers of student development and transition processes when students enter post-secondary studies. While several student development theories identify mechanisms at individual and systematic levels, Tinto (1993) identified academic integration and social integration as critical processes that contribute to persistence during students’ transition into university. Relatedly, Chickering (1993) identified the important role of identity development in the process of transition into and through university, considering the postsecondary experience to be one that is foundational to individual identity and interpersonal development. Similarly, identity influences the psychosocial experiences underpinning a successful transition into university, an extension of interactions between the individual and systems surrounding them that have occurred earlier in life, during an important developmental window. Across student development theories (e.g., Astin, 1985; Chickering, 1993; Pascarella, 1985; Schecter, 2011 ;Tinto, 1993) Developing a strong sense of belonging within supportive institutional conditions and receiving support for authentic identity development are critical factors contributing to student engagement and success.

Institutional conditions are critical to a student’s successful transition into university, and conditions are often shaped by interpersonal dynamics among the members of a particular community. Meyer (2003) explored the unique psychosocial stressors impacting lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations, demonstrating that LGB individuals experience additional, often frequent, and deleterious stress associated with discrimination, harassment, and hostile conditions within their environments. Meyer coined the term ‘minority stress theory’ to explain the additional stress burden often facing minority communities, which is an important theoretical framing to understand disparities in outcomes among populations with minority gender identities and sexual orientations. Minority stress is notably important given the important role stress plays in impacting academic performance during transition to university, which will be further discussed later in this chapter.

Integrating these three theoretical frameworks – ecological systems, student development, and minority stress – we know that 2SLGBTQIA+ students carry their developmental experiences prior to postsecondary education with them into university while navigating their own contemporary identity development and often elevated psychosocial stress during an important developmental window. Informed by these theoretical frameworks, key considerations promoting a positive transition into a new living, learning, and social environment for 2SLGBTQIA+ students require establishing conditions that promote social integration, sense of belonging, and affirming conditions that enable healthy ongoing identity development.

Current Climate: 2SLGBTQIA+ Programs, Services, and First Year Experiences: Insights from the Pan-Canadian First-Year Experiences & Students in Transition Survey

Despite theoretical and practical evidence suggesting that tailored programming for 2SLGBTQIA+-identifying first-year students might drive positive outcomes, several Canadian institutions do not offer such programs, or fail to make them accessible to incoming students. For instance, Schenk Martin et al. (2020) qualitatively assessed 45 webpages from 33 post-secondary institutions in Ontario, Canada, and found that 42.4% did not explicitly include 2SLGBTQIA+-tailored programming for students in any year.

Moreover, with reference to the data collected for the purpose of the Students in Transition study, of the 51 institutions sampled, twelve (23.5%) indicated that their institution offers on-boarding programming to assist with the transition into university for 2SLGBTQIA+ identifying students, with the remaining 39 (76.4%) institutions indicating they did not. Participation in the programming is not required at any participating institution, and the most common university area responsible for this specialized programming was Student Affairs.

Among the institutions offering specific transitional programming for 2SLGBTQIA+ students, nine (75%) evaluated the effectiveness of their program, using approaches such as articulated learning outcomes, program evaluations, and attendance records. Most of this feedback was collected via surveys, with one institution also providing a verbal debrief for participating students. Seven institutions offered the program to incoming students prior to the beginning of the term (at least one week), seven offered the program during the first week of the term once classes had begun, and eight institutions offered their program throughout the duration of the fall and winter terms.

Insights from Sector Environmental Scan and Research on Programming

Post-secondary institutions employ a variety of strategies to cultivate safe, meaningful, and inclusive spaces for 2SLGBTQIA+-identifying students in their communities. While many Canadian post-secondary institutions have anti-discrimination and preferred name policies in place, additional resources and supports are necessary to comprehensively support the diverse and evolving needs of 2SLGBTQIA+ students.

One source of support for 2SLGBTQIA+-identifying students in Canadian post-secondary institutions comes from on-campus queer student resource centres, such as the Pride Centre at Mount Saint Vincent University in Nova Scotia or the Pride Community Centre at McMaster University in Ontario. Additionally, several institutions and/or their students’ unions allocate a portion of student fees to funding queer student societies (e.g., DalOut, Dalhousie University), which organize events and programming to foster inclusive and safe environments on campus.

Despite the value of these student-run services that are cherished by many, their nature makes it such that the onus of curating an inclusive campus environment falls on student leaders rather than the institutions themselves. Notwithstanding, many post-secondary institutions do offer institutionally-led or contracted trainings/workshops for faculty, staff and/or students on mechanisms to promote positive and welcoming learning environments for 2SLGBTQIA+ students on campus (e.g., Centennial Comes Out initiative, Centennial College; Positive Space Training, Trent University; Positive Space 101, University of Saskatchewan), and new insights into current and proposed institutionally-run programming is slowly emerging.

For instance, Carliner et al., (2023) describe positive implications from three newly-developed library-based 2SLGBTQIA+ programming initiatives from a Toronto university. The first consisted of a 2SLGBTQIA+ film series, the second featured a unique 2SLGBTQIA+-themed escape room, and the last consisted of weekly student-led study sessions for 2SLGBTQIA+-identifying students. Overall, program developers received consistent positive feedback from attendees, who reported that they felt welcome and safe in these spaces, that they formed new friendships and social connections as a result of the programming, and that the programming sparked thoughtful discussions (Carliner et al., 2023). Additionally, initiatives such as the “Rainbow Writes” program developed to promote wellbeing in 2SLGBTQIA+ youth (aged 14-18) have also been shown to increase participants’ self-esteem, confidence, and feelings of social connectedness (Harrison, 2021).

Despite these recent inquiries positively advancing our understanding of currently available services, research on institutionally administered 2SLGBTQIA+ programming for first-year students specifically remains inadequate. There is a dearth in research investigating the scope, prevalence, and effectiveness of first-year 2SLGBTQIA+ programming in Canada, making it difficult to examine how effective or meaningful existing programs are, or how they may be improved upon. Nevertheless, there is extensive literature demonstrating that a student’s sense of belonging and wellbeing in their first year promotes strong academic and social outcomes (e.g., Freeman et al., 2007; Ribera et al., 2017; Walton & Cohen, 2011) and factors such as on-campus engagement, participation in student groups, and feelings of safety and inclusivity are all known contributors to fostering belonging and well-being.

The implementation of first year programming specifically tailored towards fostering belonging and well-being in 2SLGBTQIA+ students holds great potential in providing social, emotional, academic, and developmental benefits. However, it is crucial to acknowledge and consider that each student entering post-secondary studies has a unique life experience and identity, therefore spaces dedicated to promoting 2SLGBTQIA+ pride and safety must equally embrace and celebrate diverse identities, such as those with all different races, backgrounds, and abilities. For instance, if a space claims to be inclusive and safe for those with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities but lacks accessibility for those using wheelchairs, then the space is not welcoming to all students.

Furthermore, disparities in outcomes within the 2SLGBTQIA+ community underscore an urgent need for holistic and informed supports. For example, while queer and transgender youth have a significantly higher risk of experiencing suicidal thoughts and behaviors when compared to their non-queer peers (Figueiredo & Abreu, 2015), the risk is even higher among Black queer and transgender youth (Green et al. 2021). It is imperative for institutional leaders to approach first year 2SLGBTQIA+ programming with an intersectional lens to ensure that foundational conditions are established and maintained to comprehensively support diverse and overlapping student needs.

Insights from Research and Assessment on 2SLGBTQIA+ Student Needs, Experiences and Outcomes

The importance of fostering equitable learning environments that support students in their academic and extra-curricular pursuits, identity development, and maintenance of their overall health cannot be overstated. Research indicates that when undergraduate students are in good health, their likelihood of academic success increases (El Ansari & Stock, 2010). Additionally, students who report greater sense of belonging during the first year of post-secondary studies tend to perform better academically and are more likely to return to their studies after their first year, measured through higher first to second year retention rates (Davis et al., 2019).

A measure of wellbeing that predicts academic success is flourishing (e.g., Datu, 2016; Ezekiel, 2021). Generally, flourishing represents a state of psychological and social wellbeing where an individual feels a sense of happiness, connection, engagement, and purpose in their day-to-day life, typically with the presence of mental health, or an absence of significant mental health struggles (Keyes, 2002; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2016). Conversely, languishing refers to a less favourable state of wellbeing, where an individual may experience poor mental health, disconnection, lack of purpose, or a presence of significant mental health difficulties (Keyes, 2002; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2016). Those not distinctly flourishing or languishing are considered to have moderate mental health (Keyes, 2002). Importantly, students beginning their post-secondary education are more vulnerable to languishing mental health as they often experience isolation and/or feel overwhelmed with the transition, among other factors (Knoesen & Naudé, 2017).

Research has demonstrated discrepancies in mental health among 2SLGBTQIA+-identifying students, who are more likely to experience languishing mental health and less likely to experience flourishing mental health compared to their non-2SLGBTQIA+ peers (Ezekiel, 2021; Oh, 2022). Specifically, an analysis of the 2016 National College Health Assessment Canadian Reference Group revealed that transgender and non-binary students experienced languishing mental health at a rate of 17.3% compared to only 9.4% of their cisgender peers. Moreover, 14.6% of students with diverse sexual orientations experienced languishing mental health, compared to only 8.3% of heterosexual students (Ezekiel, 2021). In the same study, disparities in mental health fully mediated any disparities in academic performance within these student communities, underscoring a learning imperative for focusing on institutional actions to mitigate barriers and stressors that disproportionately impact the wellbeing of 2SLGBTQIA+ students, while building upon protective community resilience factors such as sense of belonging.

Research has also shown that individuals holding multiple marginalized identities (e.g., racialized students, students with physical disabilities, students with psychological conditions) are more likely to experience languishing mental health compared to students holding only one marginalized identity (Ezekiel, 2021). This finding is intuitive given that minority stressors are cumulative (Green et al., 2021a), and the risk of languishing mental health can be exasperated in the presence of stressors (Keyes, 2005). For instance, Green et al. (2021) found that youth (aged 13 to 24) in the United Stated who reported experiencing four or more minority stressors were 12 times more likely to attempt suicide compared to those who did not report any minority stressors. Moreover, 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals, compared to their non-2SLGBTQIA+-identifying peers, are more likely to experience sexual violence (Messinger & Koon-Magnin, 2019), physical violence (Ray et al., 2021) and poverty (Badgett et al., 2019), further contributing to the disproportionate stress levels experienced by queer-identifying individuals.

Encouragingly, feelings of sense of belonging, social support, and acceptance have all been identified as contributors to positive mental health in 2SLGBTQIA+ post-secondary populations (Leung et al., 2022) and these factors can be enhanced with specialized and general post-secondary programming. Additionally, 2SLGBTQIA+ students in Canada who perceive their campus climate to be diverse have been shown to report higher levels of belonging (Parker, 2021) and students who feel a strong sense of belonging in their institution have higher program retention rates (Davis et al., 2019), highlighting potential for positive individual and institutional outcomes when allocating resources towards creating an accepting and validating environment. Sense of belonging has been shown to mediate the negative relationship between heightened experience of stress and reduced academic performance during students’ transition to university (Ezekiel, 2021), making it a promising area of focus for first year experience programming and support.

Assessing 2SLGBTQIA+ First Year Experiences to Inform Local Action

Dalhousie University conducted a First Year Experiences Survey (2022) for quality assurance purposes, to inform institutional efforts to enhance transition to university and first year student engagement[1]. Findings from the survey identified areas of strength and opportunities for institutional improvement in supporting the transition into university for 2SLGBTQIA+-identifying students. There were several significant differences in item-level responses between those with diverse sexual orientations (LGB+) compared to those with heteronormative sexualities (non-LGB+); note that lower scores indicate higher endorsement of each construct. For instance, LGB+ students (N = 85) reported feeling slightly less comfortable living in their residence accommodations (M = 2.06, SD = 0.99) compared to their non-LGB+ peers (N = 177; M = 1.76, SD = 0.79); t(260) = -2.67, p = .01, and LGB+ students (N = 111) reported less favourable overall first-year experiences (M = 2.24, SD = 1.06) compared to their non-LGB+ peers (N = 285; M = 2.00, SD = 0.85); t(166.9) = -2.19, p = .032. The disparity in overall first year experience was also observed when comparing gender-diverse students and their cis-gender peers, with gender-diverse students (N = 30) reporting slightly less favourable first-year experiences (M = 2.47, SD = 1.12) compared to their cis-gender peers (N = 376; M = 2.03, SD = 0.88); t(32.0) = -2.13, p = .04[2]. See Figures 1 (sexual orientation) and Figure 2 (gender identity) for frequencies of students who responded favorably to questions regarding their overall first-year experience and comfort living in residence by group.

[1] The Dalhousie University First Year Experiences Survey (2022) was an institutional quality assurance activity. Data reported signify a sample of student experiences collected within the institution to inform its efforts to improve student transition and engagement experiences. Findings presented here are intended to inform other institutions how they might assess transition experiences of 2SLGBTQIA+ students within their own institutions and are not intended to be generalized outside of this specific quality assurance purpose.

2 Note that the degrees of freedom reported for the comfort in residence variable are pooled using the Welch-Satterthwaite correction given unequal variances between the LGB+ and non-LGB+ groups, driving the reported degrees of freedom in the adjusted test result being lower than total number of respondents in the sample.

Figure 1

Note. Participants were provided with five response options for the following statement “How would you evaluate your overall first-year experience at Dal?”: Excellent (1), Good (2), Neutral (3), Fair (4), or Poor (5). Percentages represent the proportion of students in each group (LGB+ and non-LGB+) who answered with either “Excellent” or “Good” to the above question. Pertaining to reported comfort levels in residence, participants indicated their agreement with the following statement “I felt comfortable in my residence” using a 5-point scale: Strongly Agree (1), Agree (2), Neutral (3), Disagree (4), and Strongly Disagree (5). Percentages represent the proportion of students in each group (LGB+ and non-LGB+) who indicated that they either strongly agreed or agreed with the statement.

Figure 2

Note. Participants were provided with five response options for the following statement “How would you evaluate your overall first-year experience at Dal?”: Excellent (1), Good (2), Neutral (3), Fair (4), or Poor (5). Percentages represent the proportion of students in each group (Gender-Diverse and Cisgender) who answered with either “Excellent” or “Good” to the above question. Pertaining to reported comfort levels in residence, participants indicated their agreement with the following statement “I felt comfortable in my residence” using a 5-point scale: Strongly Agree (1), Agree (2), Neutral (3), Disagree (4), and Strongly Disagree (5). Percentages represent the proportion of students in each group (Gender-Diverse and Cisgender) who indicated that they either strongly agreed or agreed with the statement.

Encouragingly, no statistically significant differences were found between LGB+ and non-LGB+ students, nor between gender-diverse and their cisgender peers, in their endorsements of feeling at home on campus, their beliefs regarding availability of supportive resources on campus, several indicators of academic engagement and academic efficacy, nor intention to return to Dalhousie the following academic term. Moreover, despite significant differences on several relevant constructs between 2SLGBTQIA+ students and their peers (e.g., overall first-year experience), most 2SLGBTQIA+ students report positive outcomes overall. These findings continue to inform institutional efforts to enhance the first-year experience of 2SLGBTQIA+ students living in residence and through a broader institutional transition engagement framework. Examples of these efforts have included examination of gender and sexual orientation inclusive language in residence application processes, approaches to roommate pairing that affirm students’ identities and preferences, and establishment of a 2SLGBTQIA+ and Allies living and learning community in residence at the University. They also offer an example of how in-depth assessment of the first-year experience within an institutional context can inform specific initiatives to address disparities in experience between 2SLGBTQIA+ students and their non-2SLGBTQIA+ peers. Bridging local assessment, student engagement, and analysis of student experiences within an institution or community with the evidence-informed frameworks explored below can be an effective approach to drive impactful actions and applications locally.

Institutional Action & Promising Practices

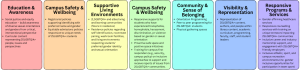

Figure 3

Note. Promising Institutional Actions to support successful transition of 2SLGBTQIA+ students into postsecondary education.

Findings from the updated First Year Experiences study and broader research demonstrate that only a small portion of postsecondary institutions offer dedicated programming designed to responsively meet the needs of first-year 2SLGBTQIA+ students, who continue to experience disparities in academic and wellbeing outcomes (e.g., higher attrition rates; Gorman & Brennan, 2023), points to a need for continued concerted effort at the institutional level, and broader postsecondary sector in Canada. The Council for the Assessment of Standards (CAS) in Higher Education produces a best practice guide, informed by experts across North America, which can inform institutions seeking to offer high-quality and evidence-informed supports for 2SLGBTQIA+ students as they transition into postsecondary education (Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education, 2023). Drawing from CAS, and the broader research within this article, the following framework offers promising practices for institutions seeking to increase responsive supports for 2SLGBTQIA+ students as they transition into university:

As institutions contemplate adding responsive programs, supports, and services for 2SLGBTQIA+ students, the promising practices outlined above and frameworks such as CAS clearly identify that close collaboration with multiple campus offices are essential to driving meaningful institutional change. Additionally, these standards recommend intentional setting of program and service goals, intended student learning and development outcomes, and approaches to measure effectiveness and outcomes to ensure investments are having the positive intended effect for 2SLGBTQIA+ students.

In an interview with Olivia Fader after her first year working in a dedicated 2SLGBTQ+ advisor role at Dalhousie University, Olivia discussed the following in terms of needs and promising practices for institutions looking to expand support. First, Olivia meets with a disproportionate number of first-year students, who are often living without their parents for the first time, and many are undergoing a long-awaited rapid identity shift during the transition to university from high school. Specifically, many students seek out gender-affirming care in their first year of university. Students often raise concerns about the implications of publicly changing their name or pronouns, as they are often economically tied to their families, who might not know about their identity(ies),or might not yet accept them.

She also highlighted the importance of not only having a dedicated advisor or liaison available to students to assist in finding resources, but in actually having a variety of resources accessible. An important element in streamlining the process of connecting students with timely care at Dalhousie is the fact that four Dalhousie physicians are members of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), thus students have convenient access to physicians trained in gender-affirming health care. Having these physicians located on campus is extremely useful for students looking for affirming and informed care, highlighting the importance of a multidisciplinary and collaborative approach when working to expand supports.

Olivia emphasized the utter importance of physical spaces dedicated to queer conversation and collaboration, and pointed out that informal spaces (e.g., open-door hub for queer students and staff) may often be even more valuable than formal spaces (e.g., planned events on campus) as it allows for folks to connect more organically on their own terms. Moreover, a large range of events and programming is necessary (e.g., sober events, low stimulus events, “louder” events, such as drag shows or sex toy bingos), given the diverse interests and needs of queer folks.

Finally, Olivia emphasized the importance of making queer students and staff visible to each other within their institutions to foster a sense of community, help folks realize that they are not alone, and show them that there are queer folks and allies all around them with similar life experiences, interests, and motivations.

Overall, implementing comprehensive and informed 2SLGBTQIA+ programming for first-year students, informed by the aforementioned frameworks and promising practices, holds potential in establishing academic and living environments where 2SLGBTQIA+ students can flourish personally, socially, and academically, contributing to their likelihood to remain engaged in and complete their studies.

Conclusions

Personal and social wellbeing are critical factors contributing to learning, academic performance, and retention among 2SLGBTQIA+-identifying students during the transition into postsecondary education. The Students in Transition study has identified that the majority of postsecondary institutions in Canada do not currently offer dedicated programs and services to support the first-year experience of 2SLGBTQIA+ students. Broader research has identified student wellbeing and sense of belonging as evidence-informed areas of institutional action to support academic performance and retention among 2SLGBTQIA+ students. Many institutions and student groups have developed promising initiatives to support their sexually and gender diverse community, including community programming, physical gathering spaces, gender-affirming healthcare, and professional student affairs supports who partner with offices across institutions to create more responsive and supportive institutional conditions through policy and practice evolution. The Council for the Advancement of Standards in Postsecondary Education also offers a comprehensive framework to guide postsecondary institutions in their efforts to build dedicated 2SLGBTQIA+ community supports within their local context. Overall, our exploration in this chapter identifies both promising progress, as well as significant opportunity to continue to build institutional conditions that will enable 2SLGBTQIA+ students to thrive during their transition to college or university. As postsecondary institutions realize their potential to build inclusive and supportive environments for 2SLGBTQIA+ learners, we will in turn be doing our part to maximize the potential of sexually and gender diverse students to thrive as they contribute their strengths and gifts to our broader communities and society.

References

Astin, A. W. (1985). Involvement: the cornerstone of excellence. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 17(4), 35-39.

Badgett, M., Choi, S., & Wilson, B. D. (2019). LGBT Poverty in the United States: A study of differences between sexual orientation and gender identity groups. UCLA: The Williams Institute. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/37b617z8

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2000). Ecological systems theory. Oxford University Press.

Carliner, J. & Walsh, B. (2023, August 17-18). Innovating for inclusion: 2SLGBTQ+ outreach and programming at the University of Toronto Libraries [Paper presentation]. 88th IFLA World Library and Information Congress; Satellite Meeting: ‘The Library is open’: creating safe working environments for LGBTQ+ library employees and marketing supportive LGBTQ+ services, Rotterdam, Netherlands.https://repository.ifla.org/bitstream/123456789/2806/1/s10-2023-carliner-en.pdf

Chickering, A. W., & Reisser, L. (1993). Education and Identity. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers, 350 Sansome St., San Francisco, CA 94104.

Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (2023). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer+ Programs and Services. In J. B. Wells & L. K. Crain (Eds.), CAS professional standards for higher education (Version 11).

Datu, J. A. (2016). Flourishing is associated with higher academic achievement and engagement in Filipino undergraduate and high school students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9805-2

Davis, G. M., Hanzsek-Brill, M. B., Petzold, M. C., & Robinson, D. H. (2019). Students’ sense of belonging: the development of a predictive retention model. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v19i1.26787

El Ansari, W., & Stock, C. (2010). Is the health and wellbeing of university students associated with their academic performance? cross sectional findings from the United Kingdom. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(2), 509–527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7020509

Ezekiel, F. (2021). Mental Health and Academic Performance in Postsecondary Education: Sociodemographic Risk Factors and Links to Childhood Adversity (Doctoral dissertation).

Freeman, T. M., Anderman, L. H., & Jensen, J. M. (2007). Sense of belonging in college freshmen at the classroom and Campus Levels. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.3200/jexe.75.3.203-220

Figueiredo, A. R., & Abreu, T. (2015). Suicide among LGBT individuals. European Psychiatry, 30, 1815. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-9338(15)31398-5

Garzón-Umerenkova, A., de la Fuente, J., Amate, J., Paoloni, P. V., Fadda, S., & Pérez, J. F. (2018). A linear empirical model of self-regulation on flourishing, health, procrastination, and achievement, among university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00536

Green, A. E., Price, M. N., & Dorison, S. H. (2021a). Cumulative minority stress and suicide risk among LGBTQ youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 69(1–2), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12553

Harrison, C. (2021). Rainbow Writes: Peer-Led Creative Writing Groups’ Potential for Promoting 2SLGBTQ+ Youth Wellbeing (2392). [Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive), Wilfrid Laurier University]. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/2392

Keyes, C. L. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.73.3.539

Keyes, C. L. (2002). The Mental Health Continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Knoesen, R., & Naudé, L. (2017). Experiences of flourishing and languishing during the first year at University. Journal of Mental Health, 27(3), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1370635

Leung, E., Gomez, G. K., Sullivan, S., Murahara, F., & Flanagan, T. (2022). Social Support in Schools and Related Outcomes for LGBTQ Youth: A Scoping Review. Discover education, 1(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1923532/v1

Messinger, A.M., Koon-Magnin, S. Sexual violence in LGBTQ communities. In: O’Donohue W, Schewe P, eds. Handbook of Sexual Assault and Sexual Assault Prevention. Springer; 2019:661–674. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-23645-8_39

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychol Bull., 129(5), 674–697. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2011.07.011

Oh, H. (2022). Flourishing among young adult college students in the United States: Sexual/gender and racial/ethnic disparities. Social Work in Mental Health, 21(4), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2022.2155502

Parker, E. T. (2021). Campus climate perceptions and sense of belonging for LGBTQ students: A Canadian case study. Journal of College Student Development, 62(2), 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2021.0019

Pascarella, E. T. (1985). Students’ affective development within the college environment. Journal of Higher Education, 56(6), 640–663. https://doi.org/10.2307/1981072

Ray, T. N., Lanni, D. J., Parkhill, M. R., Duong, T.-V., Pickett, S. M., & Burgess-Proctor, A. K. (2021). Interpersonal violence victimization among youth entering college: A preliminary analysis examining the differences between LGBTQ and Non-LGBTQ Youth. Violence and Gender, 8(2), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2020.0076

Ribera, A.K., Miller, A.L., & Dumford, A.D. (2017). Sense of Peer Belonging and Institutional Acceptance in the First Year: The Role of High-Impact Practices. Journal of College Student Development 58(4), 545-563. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0042.

Schecter, B. (2011). “Development as an aim of education”: A reconsideration of Dewey’s vision. Curriculum Inquiry, 41(2), 250-266.

Schenk Martin, R., Sasso, T., & González-Morales, M. G. (2019). LGBTQ+ students in Higher Education: An evaluation of website data and accessible, ongoing resources in Ontario universities. Psychology & Sexuality, 11(1–2), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2019.1690030

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Pieterse, M. E., Drossaert, C. H., Westerhof, G. J., de Graaf, R., ten Have, M., Walburg, J. A., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2015). What factors are associated with flourishing? Results from a large representative national sample. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1351–1370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9647-3

Siddiqi, A., Irwin, L. G., & Hertzman, C. (2007). The total environment assessment model of early child development. Vancouver: Organización Mundial de la Salud

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Curses of Student Attrition (Second). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023), 1447–1451. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198364