Main Body

I. General Introduction

Tiffany Leung and Anthony Rosborough

A. Basic Principles of Intellectual Property

To the ordinary passerby, the term “intellectual property” may seem to be an abstract phrase that applies to the world of “academics” and “professionals”—a world beyond that of “ordinary individuals.” However, intellectual property (IP) is, in fact, deeply woven in people’s daily lives.

Consider an object with which most of us are familiar: a video game. When an individual purchases a video game, they acquire ownership of a digital copy of the game, which they can then download onto the game console they own to play. However, even if they own the copy of the game, they have no right over the game’s IP. The content of the game, such as the character designs or background music, are copyrighted by the game company. The player cannot reproduce or upload the game’s contents onto the Internet without the owner’s permission, or else they will infringe on the owner’s copyright. They cannot use the logo design of the game on similar merchandise without permission, or else they will infringe on the company’s trademark rights and copyright. No other game manufacturer can construct or sell a video game console with the same functionality, since this right is reserved for the patent holder. Nor can they reproduce the console’s aesthetic appearance onto another product, since this right is reserved for the industrial design holder. Evidently, many different forms of IP rights can overlap and co-exist in single commonplace objects.

IP and Society

IP, however, is not just a static, finite category of assets that exist in our world. Each new technological development requires us to further create and clarify its boundaries. Take the rise of virtual reality, for example. This technology has generated new questions about the limits of trademark rights and copyright. Do IP rights (IPRs) granted to a trademark holder extend to the virtual world?

In addition, we have begun to more critically assess IPRs and their role in social justice. An area rife with social justice issues is the relationship between IPRs and traditional knowledge. When the basis for many IPRs depends on assigning rights to a single holder, how is this compatible with an Indigenous communi-ty’s collective traditional knowledge on medicinal uses for plants? If a researcher appropriates and uses this knowledge to create a product, which they subsequently patent, what recourses can the Indigenous community ask for, since the community did not patent this knowledge?

Issues between IP and access to knowledge, as well as access to medicine, continue to be controversial. How does one balance copyright with access to knowledge? What implications do stricter copyright laws have on access to information? Should governments favour the rights of copyright holders, or the rights of the public to an accessible body of valuable knowledge? Similarly, how should we regulate IP to achieve an appropriate balance between patent rights and access to medicine? Strong patent laws encourage inventors to create more useful products, but these patented products can be too expensive for less developed countries to afford. How do we address the needs of less developed countries who are unable to access even essential life-saving medicine due to IPRs?

How we define and shape IP rights reflects our social values, and it also shapes our social visions of the future. Thus, it is important to gain an understanding of the fundamentals of IP.

What is IP?

IP refers to the socially, culturally, and economically useful products of the human intellect. IP rights are rights that grant the holder the power to legally stop others from using their IP without their consent. Sometimes objects can be protected by more than one IP right, as seen with the video game example above.

IP and the physical property that embodies the IP are not the same. IPRs only grant the holder protection of the holder’s intellectual assets. IPRs do not grant the holder protection of the physical property that carries their intangible assets. Conversely, an individual who purchases a physical item containing IP owns the physical item but does not own the intellectual content in the physical item.

IPRs are territorial. An individual who has an IPR in Canada does not automatically have an IPR in any country in the world. In some cases, the individual may need to acquire an IPR in another country by following the other country’s IP registration processes. There are some international treaties that simplify these registration processes for patents and trademarks.

Like other property rights, IP rights are not absolute and are subject to boundaries. Most IP rights are characterized by three inherent limits: 1) the definition of protectable subject matter; 2) the criteria for protection; and 3) the limited duration. Any object that does not fall within the definition of protectable subject matter, does not meet the criteria or the protection, or is no longer protected, is in the public domain. For example, ideas, facts, legislation, and court decisions do not qualify for copyright protection. Trademark protection will not be conferred on ordinary surnames, generic terms, or trademarks that have since become generic terms, such as escalator. Some unpatentable subject matter include scientific principles, natural phenomena, abstract theorems, and methods of medical treatment. Subject matter in the public domain can be manufactured, used, sold, modified, and distributed without any restriction.

In Canada, the federal Parliament has been given the power to legislate in matters concerning copyright and patents under sections 91(23) and 91(22) of the Constitution Act 1867 (“Copyright” and “Patents”, respectively). Provincial legislatures have jurisdiction over passing-off and breach of confidence under section 92(13), “Property and Civil Rights in the Province.” Some IP rights fall under either federal or provincial jurisdiction. Industrial design and integrated circuit topography are sometimes seen as covered under copyright. Plant breeders’ rights are accepted as covered by patents, and trademarks are normally seen as covered by section 91(2), “Regulation of Trade and Commerce.” Both unregistered and registered trademarks are protected by legislation (Kirkbi AG v Ritvik Holdings Inc., 2005 SCC 65).

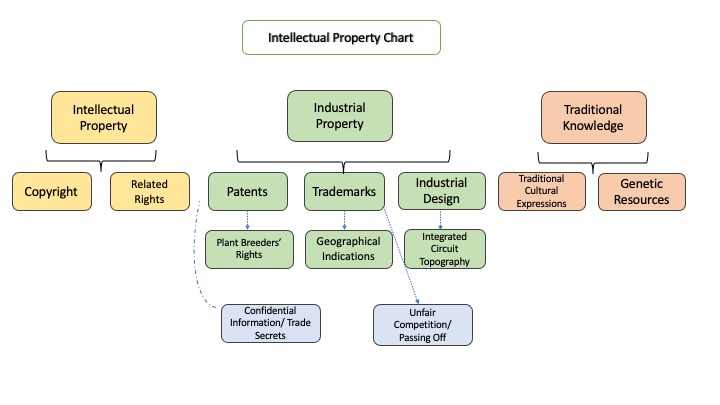

“IP” is a broad umbrella that can be sub-divided into three branches: intellectual property, industrial property, and traditional knowledge. Intellectual property rights tend to include primarily more artistic and cultural subject matter, industrial property rights tend to include primarily industrial or market-related subject matter, and traditional knowledge involves rights related to Indigenous forms of intellectual innovation. There are also private causes of action related to IP: unfair competition law, passing off, confidential information, and trade secrets.

B. Intellectual Property Rights

Intellectual property rights consist of copyright and related rights. These rights are broadly viewed as applying more often to artistic and cultural subject matter.

Copyright

Copyright is primarily concerned with the right to produce, reproduce and communicate to the public one’s own work, although it includes many other rights in relation to the creation, production, and exploitation of artistic, literary, dramatic, musical, and scientific works. The duration of a copyright holder’s right is the author’s life + 70 years after their death.

Some examples of subject matter include novels, paintings, choreography, computer programs, and maps. The subject matter must meet the threshold for 3 requirements: 1) the subject matter must be fixed in a tangible form; 2) it must meet the test for originality, and 3) it must be the owner’s unique expression of ideas or facts.

Copyright protection is automatic upon creation of an original work of authorship. According to s. 5(2) of the Berne Convention, formalities on the existence or exercise of copyright are prohibited. Rights owners can take voluntary steps to protect their subject matter, like marking “©” on their work and by registering their work at the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO).

Related Rights

Related rights, also known as neighbouring rights, is primarily the sole right to reproduce and communicate to the public performances, broadcasting signals, and sound recordings. The criteria for IP protection of related rights and copyright differ. For copyright, one of the requirements is originality, whereas originality is not a criterion for related rights.

A performer is an individual who interprets literary or artistic works. They have rights over their public performances—whether the performances are live, broadcasted, or in the form of phonograms. A producer of sound recordings has rights over their publicly accessible subject matter, and a broadcasting organization has rights over the communication waves emitted from their radio, television, or satellite station to the public. Related rights last for 50 years from the date of fixation or performance. The Copyright Act outlines the criteria for the protection of each subject matter.

C. Industrial Property Rights

Industrial property rights include patents, trademarks, industrial design, geographical indications, plant breeders’ rights, and integrated circuit topography. These rights are often seen as rights that protect commercial or industrial innovations.

Patent

A patent is the exclusive right to make, use, sell or grant licenses on one’s invention for up to 20 years from the date of filing the application. An invention can include the development of new processes, machines, chemical composition, art, products—or improvement on any of these types of existing inventions.

The invention must be 1) new; 2) useful; and 3) inventive to qualify for patent protection. The individual must also have their patent application formally examined by a patent examiner at CIPO to see whether the invention meets the substantive protection criteria, as well as the formal requirements of the Patent Act. In exchange for protection, the inventor must disclose a complete description of their invention to the public.

Trademark

Trademark protection gives the holder the exclusive right to use a sign to distinguish the goods or services of one company from those of another company. This right lasts for up to 10 years, renewable for subsequent periods of 10 years. The sign can be anything from a distinct logo, a distinct colour schematic, or a specific scent. For a sign to qualify as a trademark, it must fulfill the legal requirements outlined in the Trademarks Act.

A mark does not have to be formally registered with CIPO to be valid. An individual can use the symbol “™” for unregistered trademarks. The symbol “®” indicates that the mark is officially registered.

Industrial Design

An industrial design right is the exclusive right to use, make, and sell the two or three dimensional appearance of a finished product for up to 15 years. This design can be a combination of the product’s shape, pattern, ornament, colour or configuration. A protectable industrial design must be new and unique. Its uniqueness and novelty must come from its aesthetic design alone, not its function or method of construction. The design must be registered with CIPO to acquire protection.

A geographical indication (GI) is a mark used to indicate the geographical origin of goods. These goods can be wines, spirits, agricultural products, or food. A GI signals to consumers that the product has characteristics or qualities unique to that geographic location. It can also be an indicator of high-quality and reputable products. GIs are regulated inside the Trademarks Act. For example, the GI “Parmigiano-Reggiano” informs the consumer that the cheese is from the Italian provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Bologna, and Manuta—and it will thus have a nutty flavour and grainy texture. Only if a GI is formally registered with CIPO, can the holder prevent producers or manufacturers from outside the geographical region from using the GI.

Plant Breeders’ Rights

Plant breeders’ rights (PBR) grant the holder the exclusive right to primarily control the use, production, licensing, importation, and exportation of a new plant variety for up to 25 years— if the variety is a new tree or vine—or 20 years in other cases. The criteria to qualify as a new plant variety are that 1) the plant must be clearly distinguishable from other varieties by at least one characteristic; 2) its distinguishing qualities must be uniform among various plants within the variety; and 3) the distinguishing qualities must be stable—in that these qualities will be reproduced with each subsequent generation. If the holder can satisfy these three qualifications, they must register the variety with the Plant Breeders’ Rights Office for protection.

Integrated Circuit Topography

Integrated circuit topography (ICT) grants the owner the sole right to produce and reproduce the topography, as well as control the importation and exportation of products that use the topography, for up to 10 years (Integrated Circuit Topography Act SC 1990 c 37 s 5). An ICT refers to the layout of an electronic circuit. To qualify for IP protection, the ICT must be a novel layout and developed through intellectual effort. The holder must register the topography with the Office of the Registrar of Topographies to acquire an IPR.

D. Traditional Knowledge

There is no universally accepted definition for traditional knowledge (TK), although it is generally understood as the ever-evolving body of intellectual knowledge cultivated by Indigenous people. TK often involves the cultural skills, know-how, practices, and other innovations developed by Indigenous people collectively over generations. Within TK, there are traditional cultural expressions (TCEs) and genetic resources (GRs).

Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs)

TCEs are the intangible and tangible cultural manifestations of TK that are passed down generations. This can include oral storytelling, folk dances, symbols, artwork, hunting, and medicine. TCEs facilitate the social and cultural identity formation of Indigenous people.

Genetic Resources (GRs)

Genetic Resources (GRs) are the genetic material of natural resources, including plants and animals, that have economic value. GRs themselves are not IP. However, Indigenous groups have developed unique methods to cultivate, use, and conserve GR over generations, and these GRs have often been used as the basis for their innovations, such as unique medicine.

Relationship between TK and IPRs

There is no formal IP legislation at our national level or at the multinational level that addresses and protects TK, TCEs, or GRs directly. Existing IP statutes, conventions, principles, and private causes of actions have been used instead to provide some form of legal protection. For example, under the Trademarks Act, Indigenous groups can register TCEs as trademarks. Groups can also acquire copyright protection over their ceremonies or folk songs. Some non-IP related international conventions help provide rights to ensure the equitable use and access to GRs, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (Convention on Biological Diversity (adopted 5 June 1992, entered into force 29 December 1993) 1760 UNTS 69 art 19 (2)).

Although existing IP rights can help protect and enforce TK, TCEs, and GRs, they do not adequately provide protection for Indigenous subject matter. Indigenous subject matter often does not fulfill the criteria needed to gain full protection from IPRs. For example, IPRs often require a single owner of a subject matter, yet TK and TCEs are often collectively owned. IPRs are time limited, while TK, TCEs, and knowledge of GRs are passed down generations, and thus, temporally indefinite.

Existing IPRs are based on a Eurocentric conception of IP and thus cannot adequately address the needs of Indigenous goods. The Canadian government must continue to work closely with Indigenous groups to find concrete solutions for adequately protecting Indigenous products. The government has signed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, a declaration that asserts Indigenous people’s rights, and article 31 specifically addresses Indigenous people’s right to control and protect their TK, TCEs, and GRs. However, Canada has not implemented this resolution yet, and thus, has not established proper steps to fulfill this obligation.

It is difficult to develop an adequate TK, TCEs, and GRs legal protection system at the multinational level due to the varying IP-related interests of different countries. Some national initiatives, on the other hand, have been successful. Countries, such as the Philippines, have created national sui generis legislation to address the needs of TK, TCEs, and GRs. Canada should seek to address this issue at the national level as well, rather than waiting for a multinational solution.

New committees have been created in response to the increased awareness for the protection of Indigenous subject matter. At the international level, this includes the World Intellectual Property Organization’s (WIPO’s) Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge, and Folklore. At the national level, Canada has established the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada’s Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge Subcommittee.

For more information on the relationship between IPRs and TK, please refer to the Assembly of First Nations’ discussion paper and a booklet prepared by WIPO.

Discussion Questions

1: What do you know about TK, TCEs, or GRs? Are there other gaps or barriers you see with regards to existing IPRs’ ability to protect this subject matter?

2: Could any other non-IPRs provide adequate protection for TK, TCEs, or GRs?

E. Private Causes of Action

Trade Secrets/Confidential Information

Trade secrets/confidential information are not IP rights. They are business information that have high economic value for the owner due to their secrecy. Trade secrets cover anything that is economically advantageous for a business—such as recipes, client lists, chemical compounds, and designs. Examples include Krispy Kreme’s doughnut recipe and the New York Times’ methodology for determining its Best Sellers list.

Trade secrets do not have a time limit. A trade secret is no longer a secret when the information is discovered by others. Upon loss of secrecy, the owner loses ownership of the trade secret, and the trade secret loses economic value. There is no formal IP registration process to record trade secrets, nor are there formal IP enforcement mechanisms in place to protect them.

Subject matter is generally considered a trade secret if 1) the subject matter is kept secret; 2) it is economically beneficial to a business; and 3) the owner takes reasonable steps to maintain its secrecy. Steps to maintain its secrecy can include requiring employees to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDA) or password-encrypting the information. Should an employee breach an NDA or confidentiality agreement, then the owner can start a private cause of action.

Businesses often choose to have trade secrets if the secret cannot be covered by existing IPRs, if the owner is not ready to apply for formal IP protection, or if the business cannot afford the cost of applying for formal IP protection.

Unfair competition law/Passing off

Unfair competition law refers to a tortious act that is contrary to fair and honest business practices. The purpose of this law is to ensure a fair marketplace. An act that triggers a private cause of action is “passing off,” which occurs when a company uses a competitor’s trademark without the competitor’s permission to mislead consumers about the company’s services or goods (Paris Convention (adopted 20 March 1883, entered into force 7 July 1884) 828 UNTS 305 art 10bis(3)). Another example of unfair competition is when a company makes false allegations about another competitor with the intent of damaging the competitor’s reputation.

F. Intellectual Property and Physical Property

What are the qualities that make something a property? To what extent does intellectual property have or not have these qualities?

Similar to private property, IPRs are primarily private rights. In both cases, the rights holder can legally exclude others from using their subject matter. The subject matter can be licensed and transferred to third parties, and it can also be used as an asset and security. If an individual commits any of the acts protected by IP law without the owner’s prior consent, the owner can institute proceedings to stop these acts or obtain damages.

Although both physical property and IP have similar characteristics, there are also significant differences between the two. Most notably, IP is not a tangible asset: Broadly speaking, they are creative products of the mind. This difference has several implications.

Public vs Private Good

IP is commonly seen as a public good, by opposition to physical property which is a private good. A public good has two qualities, they are 1) non-rival and 2) non-excludable. A private good, on the other hand, is both rival and excludable

IP has the quality of non-rivalry, which means that an individual’s use of the subject matter does not decrease the subject matter’s quality or characteristic over time. Reading the same news article in the newspaper, for example, does not cause the news article to erode. On the other hand, the paper copy of the newspaper may degrade to a point where it can no longer be legible.

In addition, IP has the quality of non-excludability. IP can be used by multiple users simultaneously, whereas this is not possible with a physical product. For example, several individuals can read the same version of the newspaper all over the world, but they cannot use the same paper newspaper simultaneously.

Since IP has the qualities of a public good, it is more susceptible to the “free-rider problem”: Individuals consume and use IP indefinitely without any limitations, such as paying to use the good (Russell Hardin, “The Free Rider Problem,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2013)). As a result, the public good becomes overused, and those who create the public good become less incentivized to continue creating. This is often known as the tragedy of the commons, and it is an indication of the failure of the marketplace.

Duration

Another difference is that all forms of IP are time limited. There are some exceptions to this difference; trademarks, for example, can theoretically exist for an indefinite amount of time as long as it serves to distinguish the goods or services of the owner. GIs are also an indefinitely lasting IP right since the characteristics or qualities a geographical location imparts on the goods are continual and permanent. Nevertheless, nearly all IPRs are limited by time. All physical property, on the other hand, belongs to the owner indefinitely so long as the owner intends to keep it.

Access

Even though IPRs are private rights, these rights do not grant the IP holder complete jurisdiction over their subject matter. At least two rights have the potential to collide: the right of the owner of the tangible object (book, CD, mobile phone) and the right of the IP owner in the intangible work, invention or sign embodied in the object. Once the tangible object is sold to a third party user, the IP owner does not have a legal right to access the IP in that object without permission from the owner. Similarly, the owner of the tangible object does not necessarily have a right of access to the IP embodied therein except as permitted by law or by the IP rights owner.

Balance

The existence and regulation of IPRs revolve around balancing the interests of IP holders and users. IPRs can be a barrier to crucial IP like knowledge, education, and medicine—initially, then, it may seem as though IPRs should not exist. However, although IPRs are a barrier, they are also very important in incentivizing creation and innovation. Such incentivization is important in supporting our information economy as well as facilitating a community’s cultural and socio-economic development.

How do we ensure that we do not constrain innovation while also ensuring that we do not hinder the advancement of communities? How do we ensure that we protect an author’s right in their work without hindering another community’s right to a shared body of public knowledge? How do we balance an IP user’s freedom to parody or criticize with the author’s right to the moral integrity of their work? Allowing an IP holder to restrict access to such crucial IP requires careful consideration that users should also benefit from access to the holder’s IP within reason.

The balancing between the interests of IP holders and IP users takes on many forms. There are inherent limits to each IPRs (i.e. subject matter, criteria for protection, scope of protection, and duration of protection). Copyright, for example, does not cover facts or ideas. It covers expressions of facts or ideas. It must also meet the criteria of originality and fixation for protection. Its scope is narrowed by exceptions and limitations, and the copyright only lasts for the author’s life + 50 year before the subject matter enters the public domain.

International organizations such as WIPO have recently become aware of the necessity to place more weight on the needs of users rather than solely concerning itself with the needs of IP holders. For example, the 1971 revision of the Berne Convention included an appendix that offers the option for qualifying less developed countries to depart from international minimum standards of copyright protection. More recently the WIPO adopted the Marrakesh Treaty to Facilitate Access to Published Works for Persons Who Are Blind, Visually Impaired or Otherwise Print Disabled.

Courts also ensure that IP rights are properly balanced. For example, in Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada v Bell Canada (2012 SCC 36) the Supreme Court of Canada grappled with the interests of musicians, composers, and music publishers against the interests of music purchasers. The issue at hand was whether users should be required to pay royalties to SOCAN when users listened to music previews before purchasing a digital copy of a song. The court balanced the interests of both sides and ruled in favour of users, stating that music previews fall under fair dealing.

There are various balancing mechanisms to ensure that the interests of different social groups are carefully weighted. This conscious and deliberate concern with balance exists uniquely within the IP sphere, since IP only serves as a cure to symptoms of market failure.

G. Justifications and Theories Supporting Intellectual Property Rights

There are evidently notable differences between IP and physical property, and IP does not suffer from certain issues that affect physical property. Why does IP get “property-like” rights? At first glance, it seems that IPRs unduly hinder public access. What are some justifications and theories supporting IP rights? Are these justifications satisfactory? Four commonly-cited theories are discussed below.

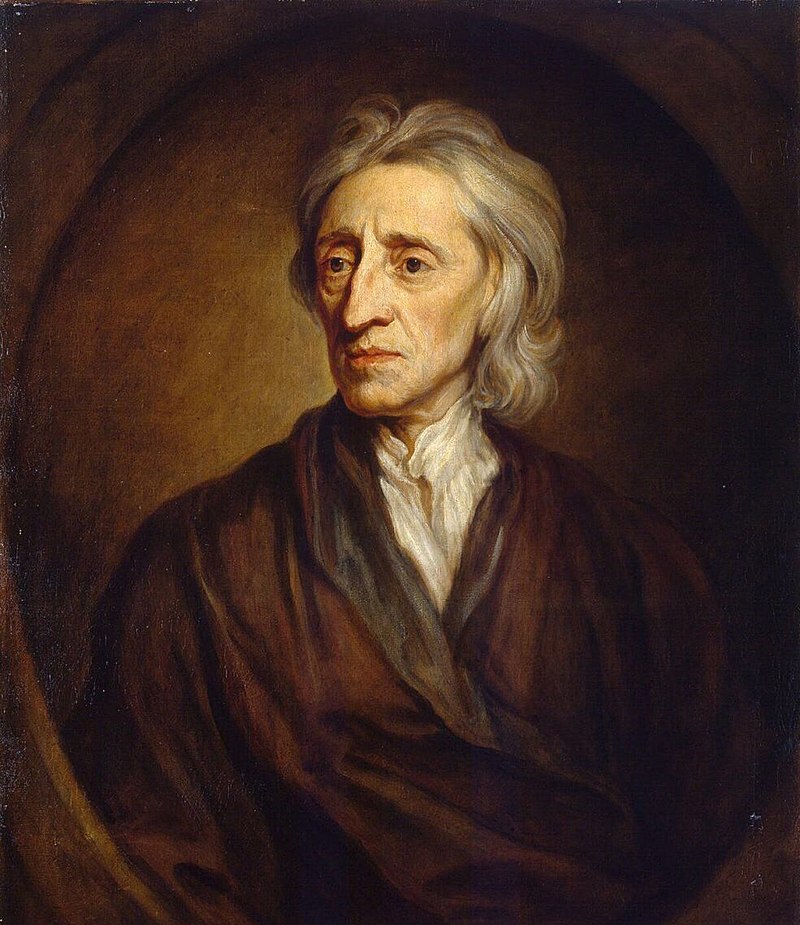

1. Labour Theory

The most prominent philosophical justification for intellectual property in the Anglo-American tradition is the labour theory – sometimes referred to as the “fairness” theory. The labour theory is loosely based upon the writings and philosophy of John Locke. The premise of this theory is that a person should be rewarded – through private property rights – for his or her labour. In the context of copyright, the labour theory posits that the law should be crafted in such a way as to ensure that property interests in literary and artistic works are provided to those who exert a type of intellectual labour in creating them.

One point of clarification worth noting – and which is often misstated – is that Locke himself made very few comments on copyright or intellectual property in devising his theories of property. Instead, intellectual property theorists, jurists and academics have applied Locke’s reasoning to copyright. This small detail is important, because some aspects of Locke’s theory of property appear to be strained when divorced from their context of real property and agricultural lands and placed in the intellectual property realm.

The importance of the historical context in which Locke was writing cannot be understated. Private property rights were understood at the time as a democratising force largely due to the need to overcome the inequities of feudalism. By privately owning and tending to land, Locke thought that individuals could become more free-acting agents and contribute more directly to the economic and political development of society. Given that Locke’s writings were not widely applied to the intellectual property system (namely, copyright) until the 20th century, the divorce of his writings from its historical context is palpable. Nevertheless, the natural right to property put forward by Locke remains a persuasive and pervasive force throughout IP theory.

In many respects, the Labour Theory acts as the impetus for the public domain. Locke conceived of a theoretical source of raw materials which is unowned, known as ‘the common’. For Locke, the right to property comes about through the exertion of labour over materials, land or resources found in the common. The common is property that exists res nullius – in other words, belonging to no one. Once a person exerts his or her labour over things found in the common, the theory posits, the value added by that labour forms the basis of private property rights. It is therefore by improving portions of the common that one acquires a natural right to them.

It is important to note the caveats noted by Locke – sufficiency and waste. The theoretical labourer can only rightfully claim a property interest in that which he or she can reasonably use. Further, the natural right to property is only justifiable to the extent it does not deny others reasonable use and exploitation of the common. These caveats introduce a necessary counterbalance to the otherwise limitless notion of natural rights to property.

Despite the pervasiveness and persuasiveness of Locke’s philosophy in IP theory, there are some difficulties that become evident when applying his allegory of physical labour over land to the creation of literary and artistic works in the context of copyright:

Intellectual Labour – The concept of intellectual labour is key for applying Locke’s theory to copyright, yet we have very little objective criterion to use in valuing this labour. In the context of physical labour over barren land, we can ordinarily apply market principles to determine the extent to which this labour brings about benefit to the land itself or the commodities it is able to produce. This reasoning does not fit easily within the context of intellectual labour.

Threshold for Entitlement – Locke’s theory proposes that the labourer obtains a property interest to portions of the common through adding his or her labour. This notion of imbuing ownership through adding labour suffers from ambiguities – namely, what is the threshold for labour added in order to warrant entitlement to property?

Sufficiency – Locke’s labour theory of property rests upon the caveat that the labourer must leave enough in the common for others to make use of. This prevents appropriation from the commons from prejudicing others. The difficulty in the IP context is determining when this balance has been achieved. Arguably, portions of the IP system reflect this caveat, including copyright fair dealing, compulsory licensing and term limits on protection. Further, the application of copyright to the digital environment makes it increasingly difficult to measure the sufficiency of the common, and more precisely, the extent of what it contains.

Assumption of Scarcity – While not stated outright, an implicit assumption in Locke’s theory is the scarcity of commodities and goods. For Locke, what made labour virtuous was that it brought about some positive benefit or product (e.g., food, building materials) which others could benefit from. While it can be argued that scientific, artistic and literary creations enrich society, this can be distinguished from the notion that there is a scarcity of these things. Even further, it is not clear how such a scarcity could be measured if it did exist.

Despite the above shortcomings in the labour theory justification for intellectual property laws, it remains persuasive throughout many jurisdictions, including Canada. As is discussed further in the Copyright chapter, British and Canadian copyright systems borrow heavily from the labour theory in espousing the “skill, judgment and labour” doctrine. While the precise tests for originality in both jurisdictions have evolved in recent decades, the underlying virtues of entitlement through labour and effort are ubiquitous in Canadian and British copyright jurisprudence.

2. Personality Theory

In contrast to the Labour Theory, the Personality Theory is concerned primarily with cherishing and protecting a bond between the creator and his or her creations. It is most commonly referenced in relation to copyright. By treating works as extensions of the creator’s personality, the theory proposes that copyright law is justified on the basis of the protection it provides to authors to control how their work is used, portrayed and monetised.

The Personality Theory is often regarded as being supported by the philosophical writings of Immanuel Kant and Georg Wilhelm Frederich Hegel. These enlightenment thinkers posited that the individual’s will is the core of his or her existence. In contrast to Locke’s conception of freedom – largely from external restraint imposed by the state – Hegel and Kant’s view was more so that freedom should be realised through the individual’s unity with a higher objective order (i.e., will, self-realisation and identity). When applied to intellectual property, the Personality Theory holds that private property rights (including copyright) are the most suitable way to ensure that individual authors or creators are able to act in unity with their free will. It is only through the institution of private property – the theory holds – that an agent can become a person and express his or her actual will.

The notion that private property enables self-expression and identity is, in some respects, intuitive. After all, individuals must be able to take control and ownership of some aspects of their physical environment in order to assert themselves and become purposeful agents in the world and society. In the context of intellectual property, this view of property can be equally intuitive. Many creators and innovators would agree that some control over their creative and inventive processes is essential to fostering their creativity and ingenuity.

In Canada, the Personality Theory is exemplified most clearly by the Copyright Act’s support and protection for moral rights. As is discussed further in the Copyright chapter, moral rights provide authors a type of continuing control over works which is independent from the economic rights to exploitation. The Act’s notion of protecting the author’s integrity and granting a right to be associated with his or her creations exemplify the type of normative values that support the Personality Theory.

As morally intuitive as the Personality Theory may seem at first blush, it does leave several issues wanting for further explanation and reconciliation. Firstly, if the primarily purpose of intellectual property rights are to protect the individual expression and identity of creators, how then can it explain and protect the practice of licensing and assigning the economic rights to others?

Secondly, the Personality Theory is ambiguous with respect to how the creator’s personality must be reflected in the work in order to attract protection. Determining this threshold requires an exploration into highly subjective considerations, including the extent to which particular forms of expression or invention may be regarded as more ideal mediums for individual expression than others. Where the creators’ personalities become the focal point of the intellectual property system, it becomes more crucial to place limits on which types of expression can properly fall within the conception of ‘authorship’.

Despite the ambiguities latent in Personality Theory, it continues to be a strong rationale for many aspects of the copyright system, particularly in continental Europe. So long as authorship remains one aspect of the copyright system – at least for measuring the extent of certain economic rights – Personality Theory will remain relevant and morally persuasive.

3. Utilitarianism/Welfare Theory

Utilitarianism is most commonly identified through the writings of British philosophers John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham. These thinkers (among others) crafted an ethical theory which views political and moral decision-making within the lens of economics. Namely, utilitarianism calls for laws and governments to be oriented in such a way as to produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. This is to be done through creating incentives and disincentives to shape behaviour in ways that produce socially beneficial results.

For Bentham and utilitarian thinkers, the actions of government and the effect of laws should be such that the greatest happiness results. As will be discussed further, the vague notion of “happiness” can in practice become deceivingly complex and indeterminate. But save for now the deeper questions of what “greatest good” or “greatest happiness” ought to mean for a given group, utilitarianism is predicated upon fairly simple and intuitive concepts.

In terms of utilitarianism’s application to intellectual property, a key premise is the notion of “public goods”. This notion is borrowed from economic theory. These are things that benefit society and maximise utility for all. The types of inventive, artistic and literary works ordinarily protected by intellectual property laws are generally regarded as public goods under the utilitarian theory. This is because they enrich society, knowledge, and human understanding. Utilitarianism holds that these works, like all public goods, share two characteristics: they are non-rivalrous, and non-excludable.

Non-Rivalry – Rival goods are those goods which, when used, prevent others from using them concurrently. One example of a rival good is a parking space. When a car occupies the parking space, no one else can make use of it. Public goods, on the other hand, are generally regarded as “non-rivalrous” in that the use by one person does not exclude others from using it concurrently. One example of a non-rivalrous good is a cinema. Unless ticket holders are lucky enough to find themselves as the only ones visiting the theatre, they will likely be enjoying the film with others. This ability to concurrently make use of a common good makes it “non-rivalrous”.

Non-Excludability – Goods are understood to be excludable when they are capable of being protected in a such a way that only certain people can enjoy them (whether concurrently or not). The cinema is also an example of an excludable good in that only ticket holders are able to watch the film. Public goods generally do not share this characteristic. This means that they are ordinarily free for all to take advantage of and potential audiences or beneficiaries can not be discriminated from one another.

One common example of a public good that is both non-rivalrous and non-excludable is a lighthouse. In maritime navigation, lighthouses are necessary not only to warn mariners of shallow water and rocks, but also to assist in coastal navigation, charting and plotting position. In other words, they act as a crucial benefit for all mariners. They are also expensive to build, establish and maintain.

Lighthouses are non-rivalrous because their use by one mariner does not preclude others from making use of them. Ostensibly any vessel that is within the range of the light is able to use it as a navigational aid. Lighthouses are also non-excludable because it is impossible to discriminate between mariners and vessels who may come to use the lighthouse as a navigational aid. Similar to FM radio, the lighthouse broadcasts a beam of light in a circular motion for all to see.

Given the example of a lighthouse, it may be tempting to adopt the view that public goods are always provided by the public sector (i.e., government), but this is not always the case. The term ‘public good’, in economic terms, may refer to things that are naturally available in the environment (e.g., air, rain water), and they may also be produced by private individuals and companies for various reasons (e.g., a hydroelectric dam). In this sense, the notion of a public good is principally concerned with the net effect of the good on society.

When applying the concept of public goods to intellectual property, the key premise is that these works and inventions benefit society by enriching knowledge and the human experience. Though difficult to quantify with precision, the utilitarian theory views these contributions to the public sphere as a type of social good that must be fostered and encouraged. From the standpoint of economists, creative and inventive works suffer from the key pitfalls of public goods—non-excludability and non-rivalry. It is for this reason that the law ought to intervene to incentivise their production.

“Public Goods” Example: A Novel

Suppose that you have written an eloquent novel about the tribulations of being a law student that is well-received by your peers. You share it with one of your classmates, and she, out of the desire to allow others to enjoy it, shares it with even more of your classmates. Even if you were able to charge the first classmate with whom you shared your novel, it would be nearly impossible for you to charge successive readers for enjoying it. After all, it was merely lent to them to read. It is in this sense that works subject to copyright protection can be considered “public goods” like lighthouses or national defence. They have social benefits, but they are also generally of high cost to create and can be easily copied and reproduced. Without sufficient incentives and protections afforded by law, it is very likely that they will not be produced in sufficient quantity to achieve maximum utility.

The utilitarian view of copyright is that the law should be crafted in such a way that the state protects authors and creators against competition and provides time-limited monopoly rights. This is considered to be a more efficient use of resources than government creating the public goods itself, or subsidising authors and creators for their works.

The jurisdiction in which we see the strongest uptake of the utilitarian view of copyright law is the United States, where Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution provides:

“[the United States Congress shall have the power] To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

By providing the legislature with the power and objective of ‘promoting the Progress’ of science and the ‘useful Arts’, the US constitution refers to the role of patent and copyright law in encouraging the proliferation of socially beneficial goods. Like all theories and justifications supporting intellectual property laws, the utilitarian view of the purpose of copyright law in turn informs how other aspects of the system are interpreted, including inventiveness, novelty, originality, creativity, authorship and moral rights protections.

4. Social/Cultural Theory

The fourth theoretical view of intellectual property laws’ purpose is Social Theory. This theory is the most contemporary and least well-known of each of the four justifications and theories. It’s also the newest in terms of its theoretical underpinnings. Its main proponents are disbursed between legal academics, sociologists, lawyers and policy-makers. Like utilitarianism, Social Theory is prospective in orientation—it looks to how copyright law can be shaped to achieve certain results. It differs from utilitarianism in that its perspective is not one of consumer choice or availability of works for consumption. In contrast, Social Theory proposes that intellectual property laws should strive to foster and support a just and attractive culture. In this sense, Social Theory borrows some of the Enlightenment thinking from the Personality Theory in that it identifies a vague (yet morally intuitive notion) set of fundamental human needs that can be supported by artistic and literary creation.

In contrast to the Labour Theory, Social Theory is not focused on an individualised notion of fairness or justice. Rather, as its name would suggest, Social Theory views the fairness or efficacy of the intellectual property system on the results it distributes to society at large. This notion of a collective social interest is key to Social Theory. Fair access to the opportunities necessary for human flourishing and the protection of identity are both key tenets.

Social Theory holds that the conditions necessary for the full realisation of a just and attractive culture loosely take shape around life, autonomy, engagement, self-expression, connection, health, privacy, and competence. Some of these may be familiar to you after reading through the main principles of the Personality Theory. But in contrast to Personality Theory, Social Theory is not fixated on the individual author and his or her personhood in the world. Rather, these conditions are more accurately understood at the public level. To achieve these conditions, Social Theory holds that they are best realised by a more equal society through participatory democracy and empowerment of individuals to contribute more directly to society.

Where Utilitarianism is principally concerned with the availability of inventive and creative works for members of society to make use of, Social Theory focuses on empowering people to make use of these works into new cultural and inventive forms. Indeed, digital technologies have made this increasingly possible in the 21st century. Where copyright law has the tendency to restrict such uses, Social Theory often looks to areas for legal reform. These areas for reform centre around fair dealing, open access, educational uses, protections for traditional cultural expressions, alternative compensation models and moral rights. Each of these aspects of the copyright system is discussed further in the Copyright chapter.

Overall, Social Theory recognises that intellectual property laws can often act to exacerbate social inequality. These rights can be used as an instrument to facilitate or hinder the development of social and cultural identity. Proponents of Social Theory contend that IP protection should seek to promote the welfare of individuals (Giovanni Battista Ramello, “Access to vs. Exclusion from Knowledge: Intellectual Property, Efficiency and Social Justice” in Axel Gosseries, Alain Marciano and Alain Strowel (eds), Intellectual Property and Theories of Justice (Palgrave Macmillan 2008)).

It is possible to apply this theory to distinct IP rights as well. With respect to patent rights, the 20 year market monopoly may hinder certain groups’ access to important products. Access to medicine, for example, remains a struggle for many less developed countries that are unable to afford the high price of life-saving medicines produced by pharmaceutical companies or to produce the medicines in their own territory (Peter S. Menell, “Property, Intellectual Property, and Social Justice: Mapping the Next Frontier” (2016) 5 Brigham-Kanner Property Rights Conference Journal). The inability to access medicine due to patents exacerbates the existing socio-economic divide between less developed and more developed countries.

IP policy can facilitate or restrict access to knowledge, education, and information (Lateef Mtima, “Copyright and Social Justice in the Digital Information Society: ‘Three Steps’ Towards Intellectual Property Social Justice” (2015) 53 Houston Law Review). IPRs have sometimes resulted in perpetuating social injustices. For example, TK-associated GRs have been patented by researchers for economic purposes without Indigenous groups’ consent and knowledge. Social justice theory posits that courts and legislators should use IPRs as a means of achieving social justice goals—particularly by favouring the dissemination of knowledge to a wide community of users. For example, the Marrakesh treaty has advanced social justice objectives by allowing copyright reproduction without the owner’s consent if the purpose of reproduction is to translate print material into other more accessible formats for individuals who are visually impaired, blind, or print disabled.

Trademark rights can exacerbate social injustices. Marks can sometimes be a symbol associated with the cultural, religious, ethnic, or social identity of a community. If another group adopts this symbol and uses it to represent their group’s goods or services, then the community may be negatively affected. For example, some sports teams use Indigenous symbols or words for their team names. However, although trademarks can perpetuate social injustices, the theory purports that trademarks can also be used to further social justice goals. For example, the appropriate use of trademarks can allow Indigenous groups to gain revenue by licensing their trademarks and displaying the authenticity of their TCEs to the public (Brigitte Vézina, “Curbing Cultural Appropriation in the Fashion Industry” (2019) 213 CIGI Papers).

In summary, there is no single universal justification to IP rights. Each justification has its strengths and its shortcomings. Different countries’ IP regimes may favour one justification over another. In the United States, the economics justification is heavily emphasized, whereas in France and Germany, the natural rights theory and the labour theory are more prominent. It is important to be aware of theories and to understand these frameworks. Understanding older and more recent paradigms can help us understand as well as critically assess contemporary IP issues—such as the potential rationales behind how different governmental bodies are handling the protection (or lack thereof) of Indigenous forms of knowledge.

Discussion Questions

1: Which justification or theory do you think Canada’s IP regime relies on?

2: Do you think there are other compelling justifications for IPRs other than those explained above?

3: Do you find the recent scholarship on IP justifications more compelling and accurate than the traditional IP justifications? Why or why not?

H. International Legal Framework on Intellectual Property

In the 19th century, the international community began to realize how problematic the territorial application of IPRs was in an increasingly globalized world. Since the legal effect of IPRs was limited to the territory of the jurisdiction in which it was conferred, an individual could freely use and consume IP subject matter originating from another jurisdiction. For countries that began to gain a reputation for being exporters of IP-based goods, the lack of protection resulted in a substantial loss of economic revenue.

The inadequacy of IPR territoriality led several European states to conclude bilateral agreements with one another in the second half of the 19th century. Bilateral agreements allowed both parties to tailor the provisions to their specific IP-related needs, such as mutually beneficial minimum standards of IP protection and scope of protection. Although these agreements were sufficient at the time, the increasingly globalized nature of the markets, alongside the development of new technology that allowed for easier dissemination of IP subject matter across national borders, resulted in the insufficiency of bilateral agreements. Bilateral agreements required time to negotiate between states, and it was too time-consuming to develop these agreements with multiple different states. As a result, multilateral agreements became a necessary response to the technological and economic developments at the end of the 19th century.

The first two international instruments drafted were the Paris Convention on the Protection of Industrial Property (1883) and the Berne Convention on the protection of literary and artistic works (1886). Both treaties aim at determining minimum standards of international IP protection. The Paris and Berne Conventions have a broad scope, compared to other international treaties that pursue narrower objectives, such as establishing an international classification system or simplifying the international registration process.

WORLD INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ORGANIZATION (WIPO)

WIPO is a United Nations body based in Geneva that handles the regulation of IP on an international level. It was officially established in 1967. WIPO’s mission is to encourage international collaboration in IP regulation, as well as to incentivize the creation of more IP to facilitate the cultural, economic, and social development of communities. The WIPO counts 193 Member states. Since international treaties establish a minimum level of protection, Member states are free to implement stricter provisions than provided under the treaties.

a) WIPO-Administered Treaties

The Paris Convention on Industrial Property (The Paris Convention 1883)

The need for an international convention addressing industrial property rights arose after an exhibition held in Vienna in 1873. Inventors did not want to showcase their inventions at this exhibition due to the absence of legal protection for their work. The Paris Convention was established in 1883 to address this concern.

The substantive provisions of the Convention fall into three main categories: national treatment, right of priority, common rules.

(1) The principle of national treatment requires that each Contracting State grant the same protection to nationals of other Contracting States that it grants to its own nationals. Nationals of non-Contracting States are also entitled to national treatment under the Convention if they are domiciled or have a real and effective industrial or commercial establishment in a Contracting State.

(2) in the case of patents, trademarks and industrial designs, the Convention requires that Member States recognize a right of priority. Whenever a regular first application is filed in one of the Contracting States, the applicant may, within a certain period of time (12 months for patents and utility models; 6 months for industrial designs and marks), apply for protection in any of the other Contracting States on the basis of that first application. Subsequent applications will be regarded as if they had been filed on the same day as the first application, giving the applicant a “right of priority” over applications filed by others during the said period of time for the same invention, utility model, mark or industrial design.

(3) The Convention lays down a few common rules that all Contracting States must follow in the area of patents and trademarks.

Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (The Berne Convention 1886)

In the 19th century, publishing companies were importing and reproducing foreign works without the IP holders’ permission. The international community agreed that an international instrument that would facilitate the regulation and protection of artistic, cultural, dramatic, and literary work was necessary, and this led to the creation of the Berne Convention in 1886.

The Convention lays down three basic principles: (1) the principle of national treatment; (2) the principle of automatic protection, meaning that protection must not be conditional upon compliance with any formality; and (3) the principle of independence of protection, meaning that protection is independent of the existence of protection in the country of origin of the work. This last principle is subject to three exceptions relating to the term of protection (where countries may apply the rule of the shorter term; art. 7(8)), the protection of works of applied art (where countries may allow the cumulation of copyright and industrial design; art. 2(7)) and the droit de suite (art. 14ter). The Convention further contains provisions setting minimum standards of protection relate to the works and rights to be protected, and to the duration of protection, as well as exceptions and limitations.

In the Paris 1971 Revision of the Berne Convention, the states’ primary concern was the effect of copyright on less developed countries. In taking into consideration these countries’ unique technological and educational needs, the Berne Convention added an Appendix which states that if certain conditions are met, the minimum standards of protection may be relaxed for less developed countries. Canada acceded the latest version of the Berne Convention—the Paris 1971 Revision of the Berne Convention, as amended in 1979—in 1998.

The International Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organizations (The Rome Convention 1961)

In the mid-20th century, increasing concern arose around how best to protect the interests of performers and phonogram producers. Certain groups, such as the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers, initially attempted to protect producers by proposing amendments to the Berne Convention. In 1960, it was decided that a new international legal convention would be created to address these needs—along with the protection needs of broadcasting organizations—and in 1961, the Rome Convention was established.

The Rome Convention includes provisions on the scope of protection afforded to performers, phonogram producers, and broadcasting organizations, as well as the duration of their rights.

The WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT 1996) and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty (WPPT 1996)

The WCT and the WPPT are dubbed the ‘WIPO Internet Treaties’. They were negotiated with the view to adapting the copyright and related rights framework to the emergence of the Internet. The WIPO attempted to modify and revise the Berne Convention as a response to these developments. However, the need for new international norms, rather than modified pre-existing international norms, soon became apparent, and both treaties were signed in 1996. The WCT is a special agreement under the Berne Convention. As a result, its provisions do not supersede those established in the Berne Convention. The WCT addresses a copyright holder’s rights in the digital environment, limitations and exceptions, technological protection measures and rights management information in relation to works made available in the digital environment.

The WPPT was drafted alongside the WCT as a result of negotiations during the WIPO Diplomatic Conference on Certain Copyright and Neighbouring Rights. Similar to the WCT, the WPPT addresses the technological developments that occurred in the late 20th-century in relation to the dissemination and use of performances and phonograms in the digital environment. The need for new international norms, rather than modifications to the Rome Convention, spurred the creation of this new treaty. Provisions in the WPPT do not supersede those established in the Rome Convention.

b) Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (IGC)

Already in the 1960s, there was a growing recognition of the importance of TK, TCEs, and GRs. In particular, the international community recognized that Indigenous subject matter is worthy of protection, that it has value as IP assets, and that the IP regime needed to be more inclusive to non-Western forms of innovation. Along with this recognition came the realization that the development of new technologies facilitated the frequent misappropriation and exploitation of TK, TCEs, and GRs. Existing international conventions, such as the Berne Convention, could not adequately protect Indigenous subject matter due to its unique nature.

In 1997, a new WIPO body called the Global Issues Division was established to assess the needs of Indigenous communities. This resulted in the creation of the IGC in 2000. The IGC is a WIPO body that functions as a forum of discussion for issues related to the development and regulation of protection for TK, TCEs, and GRs. In 2009, the responsibilities of the IGC broadened from its initial role as a forum to a committee that has the authority to propose international initiatives that can further propose initiatives to further TK, TCE, and GRs protection. In 2019 the mandate of the IGC was renewed and expanded, to include among other goals, work towards finalizing an agreement on an international legal instrument(s), without prejudging the nature of outcome(s), relating to intellectual property which will ensure the balanced and effective protection of genetic resources (GRs), traditional knowledge (TK) and traditional cultural expressions (TCEs).

c) WIPO Development Agenda

In 2004, Argentina and Brazil submitted a proposal to WIPO, requesting that it develop a plan that prioritizes the needs of less developed countries within the context of IP regulation. Other countries subsequently submitted related proposals, and this led to several discussions. In 2005, the WIPO General Assembly established the Provisional Committee on Proposals Related to a WIPO Development Agenda (PCDA) to accelerate the progress of its discussions. The PCDA initially generated 111 proposals. In the 2007 General Assembly, the PCDA and Member States agreed on 45 proposals for its development agenda and established the Committee on Development and Intellectual Property (CDIP).

The proposals range from proposed initiatives to assist less developed countries in their IP-related needs to recommendations for WIPO to follow in order to better assess and understand the impact of IP regimes in Member States. Some recommendations include encouraging WIPO to promote activities that facilitate the growth of the public domain, as well as encouraging the creation of international mechanisms to address the specific needs of TK, TCEs, and GRs.

The CDIP is a committee that oversees the implementation of the 45 proposals. This includes facilitating the implementation of the proposals, as well as monitoring, assessing, discussing, and reporting Member States’ progress in the implementation of these proposals with the General Assembly.

WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION (WTO)/ TRADE-RELATED ASPECTS OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AGREEMENT (TRIPS)

The introduction of IP into trade-related agreements came about in part because of the realization of the huge economic importance of IP protected industries (pharmaceuticals, films, videogames, trademarked goods) and in part because of the rise in counterfeit and pirated goods which affected international trade. Countries that were net exporters of IP wanted higher IP protection standards from countries with low IP standards. Divergent IP protection levels between countries were also seen as barriers to trade.

In 1993, the national delegates met in Montego Bay, Uruguay, to discuss multilateral trade issues in the context of the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade). The former GATT organization morphed into a new multilateral organization now known as the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO administers only one IP-related international legal instrument, the TRIPS Agreement, which was signed as Annex 1C of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization.

Any member of the WTO must join TRIPS. This requirement emerged when the international community found that the varied level of IP protection in different countries created economic friction.

The TRIPS is part of a broader trade agreement. Whereas WIPO administers treaties that shape IP regulation directly, TRIPS places the regulation of IP within the fora of international trade. It does not participate in the creation of IP law as such, but it does contribute to its consolidation and codification. Within TRIPS, some provisions ensure that all parties abide by minimum standards of IP protection, like the Paris and Berne Conventions. It also establishes mechanisms to handle IP infringement, including civil, administrative, and criminal procedures, as well as mechanisms to prevent infringement. In addition, TRIPS provides a dispute-settlement system.

WTO and WIPO collaborate to put in place measures to aid less developed countries in fulfilling their obligations to TRIPS. Such measures can include aiding less developed countries with adopting laws, as well as training personnel to carry out their TRIPS obligations.

BILATERAL INVESTMENT TREATIES AND FREE-TRADE AGREEMENTS

As is made clear by the approaches of both the Berne Convention and the TRIPS agreement, the general approach of these multilateral instruments is to guarantee minimum levels of protection. The result is that states are nevertheless free to agree to even higher levels of protection through separate agreements. This approach has become increasingly common in regional and bilateral free-trade agreements, leading to the adoption of the term “TRIPS-Plus” provisions.

The number of regional and bilateral free trade agreements in existence is massive. For reference, the WTO maintains a database of over 300 regional free-trade agreements. Many of these agreements include provisions which expand upon the protections in TRIPS, or otherwise offer protections where TRIPS may be ambiguous. The effect of TRIPS-Plus provisions in these agreements is multifaceted, but largely produces fragmented levels of protection among states and restrictive consequences for third party states. Overall, these consequences run contrary to the purpose and objectives of the Berne and TRIPS frameworks.

The rise in bilateral and regional free-trade agreements in recent decades has been spurred largely by changes in political and diplomatic approaches. It seems that we are now in an environment where large multilateral treaty-making is less palatable. To this end, we are likely to see the trend of TRIPS-Plus provisions in bilateral and regional agreements continue.

Similar to TRIPS, Canada is a party to the NAFTA, CETA, USMCA and CPTPP agreements that primarily deal with investment and trade, but that also include provisions governing IP. The primary purpose of these agreements is to encourage more investment and trade among the member countries by eliminating barriers on the trade of goods and services. These agreements have been developed with an eye to ensuring greater transparency, predictability, and protection for investors. Such treaties and agreements inevitably also ensure that parties who seek the benefits of beneficial trade deals adhere to standards of IP protection agreed to by all parties. The strong focus of the TRIPS and other bilateral agreements on the interests of investors and IP owners keeps on generating unabated criticism from parts of the legal community and from user organizations who denounce the heightened restrictions on access to medicines, knowledge and culture.

a) NAFTA

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was a free-trade agreement signed by Canada, the United States, and Mexico in 1992. Its provisions on IP notably included broadening copyright to include computer programs and databases.

b) CETA

The Canada and European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) is a bilateral investment treaty signed by Canada and the European Union in 2016. This agreement encourages the movement of goods and services between Canadian and EU markets. Its provisions on IP include enhanced patent protection for pharmaceutical products, and GI protection for agricultural and food products.

c) UMSCA

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) is often referred to as the updated version of NAFTA. This agreement, signed by all three countries in 2018, updates the provisions established in NAFTA to address modern issues related to trade and investment.

d) CPTPP

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is a comprehensive free-trade agreement between 11 countries in the Asia-Pacific region: Canada, Australia, Brunei, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. This agreement evolved from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an agreement that was abandoned after the United States withdrew from it. The CPTPP, signed in 2018, contains a chapter on IP regulation. In this chapter, it requires all members to ratify several other IP treaties, including the WCT, the WPPT, and the Singapore Treaty. It also outlines extensive provisions on IP rights enforcement, including border enforcement procedures and IP enforcement in the digital environment.

Due to each country’s vastly different IP values and regimes, it has become increasingly difficult to negotiate multilateral agreements. As a result, states have shifted towards negotiating bilateral investment treaties and free-trade agreements, since such agreements are meant to reinforce existing IP norms in a trade context rather than creating new law.

I. History and Development of Intellectual Property Regulation in Canada

Copyright and Related Rights

The history of Canada’s copyright legislation began with the UK’s Statute of Anne, which was also known as the Copyright Act of 1710. This Act addressed the widespread problem of individuals producing and reproducing works without the owner’s permission and without remunerating them. The Act granted booksellers and printers the exclusive right to their work’s production and reproduction for a set term of 14 years for works that were composed thereafter, or 21 years for works already in print circulation.

Passed by the Parliament of the Province of Lower Canada, the Copyright Act, 1832 was the first Canadian colonial copyright statute. The 1832 Act aimed at encouraging the emergence of “a literary and artistic nation and to encourage literature, bookshops and the local press” by granting copyright to residents of the province. Following the unification of the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada to form the Province of Canada, the 1832 Act was repealed and replaced by the Copyright 1841. The Act only granted copyright in books, maps, charts, musical compositions, prints, cuts and engravings. Copyright was awarded only if it was registered and if a copy of the work deposited in the office of the registrar of the province before publication. The author was required to be resident in the province in order to obtain copyright under the Act, though the Act was unclear on whether the work needed to have been first published in the Province (“Copyright law of Canada“, Wikipedia). The unclear status of British publishers drew the irritation of the Empire. Canada corrected the situation with the enactment of An Act to extend the Provincial Copyright Act to Persons Resident in the United Kingdom in 1847, granting British authors protection only if their works had been printed and published in the Province of Canada. The 1841 and 1847 statutes were subject to minor revision in 1859 and the requirement for the works to be printed in Canada, buried in the text, was later noticed and denounced by the imperial British government

Upon Confederation, the British North America Act, 1867 granted the federal government power to legislate on matters such as copyright. The Parliament of Canada passed the Copyright Act of 1868, which granted protection for “any person resident in Canada, or any person being a British subject, and resident in Great Britain or Ireland. This act was modified by the Copyright Act, 1875, which provided for a term of twenty-eight years, with an option to renew for a further fourteen years, for any “literary, scientific and artistic works or compositions” published initially or contemporaneously in Canada, and such protection was available to anyone domiciled in Canada or any other British possession, or a citizen of any foreign country having an international copyright treaty with the United Kingdom, but it was contingent on the work being printed and published (or reprinted and republished) in Canada.

George Munro and the Seaside Library

Where the national copyright laws of countries, like Canada and the United States, restricted protection to works produced by citizens residing in the country’s own territory, cross-border publishing ventures blossomed well into the second half of the 19th century. One prominent entrepreneur in these ventures was George Munro.

Munro was born in 1825 in Pictou County, Nova Scotia. He moved to New York in 1856, where he eventually founded the Seaside Library, a publishing company that became renowned for its cheap reprints of British and French literature. The Seaside Library reprinted works of famous authors such as Charlotte Bronte, Charles Dickens, and Jules Vernes on quartos that sold at cheap newspaper rates. These serial publications charmed North American readers, and within two years, the Seaside Library had sold over five million works without paying a penny in copyright royalties.

Munro’s re-printing practice not only hastened the passage of international copyright law, but he was instrumental in financially establishing Dalhousie University. His gifts began in 1879 and totaled approximately $350,000. He endowed professorships in English literature, history, physics, metaphysics, and constitutional and international law. Munro also endowed tutorships in classics, mathematics and left an endowment fund for competitive scholarships. Munro Day is a Dalhousie University holiday that has been celebrated since that time every year on the first Friday of February.

QUESTION: How did the adoption of the Berne Convention change this practice? What principle can authors now invoke to stop ventures like the Seaside Library?

In 1921, Canada parted ways with Imperial copyright laws with the enactment of its own comprehensive domestic copyright legislation, the Copyright Act, which came into force in 1924. Nevertheless, the 1924 Act mirrored very closely the UK Copyright Act of 1911 while acting as Canada’s implementation of the Berne Convention’s requirements (i.e., absence of formalities for protection, minimum standards of protection and term of protection). This statute laid out all aspects of copyright regulation in Canada, including works protected by the statute, the duration of rights, infringement, and remedies. Most notably, it designated the author’s life + 50 years as the copyright term. More recent legislative changes are discussed in the Copyright chapter of this book.

Patent

The 1823 Lower Canada Act marked the first instance of legislation related to patent regulation in Canada. Upper Canada and other dominions of Canada followed suit in adopting similar patent legislation.

The federal government gained jurisdiction over patents after the creation of the Constitution Act in 1867, and two years later, in 1869, Canada enacted its first country-wide patent legislation called the Patent Act.

Soon after, Canada joined the 1883 Paris Convention, which influenced its obligations to patent regulation. In particular, this convention established that patents are territorial rights.

The Patent Act was amended several times since its inception. When it was amended in 1890, it officially established the requirement that a patent must be assessed by patent examiners before protection is granted to an invention. The 1987 Amendment to the Patent Act brought two major changes: it established a ‘first to file’ system, replacing the long standing ‘first to invent’ regime, and it set the term of protection to 20 years from the date of filing of the application instead of the previous 17 years from the date of grant. In 1993, one of the current criterion for patentability, non-obviousness, was added to the Act. More recent legislative changes are discussed in Chapter IV of this book.

Trademark

Trademark regulation began with the Constitution Act in 1867. Although neither section 91 nor section 92 address the regulation of trademarks directly, it is commonly accepted that the federal government has jurisdiction over it under section 91(2), “The Regulation of Trade and Commerce.”

The first legislation that addressed trademark regulation arrived the year following Confederation. In 1868, Canada developed The Trade Mark and Design Act, an act that established a federal trademark register and supplied provisions related to trademark registration.

The first international treaty that influenced Canada’s obligations to trademark rights was the Paris Convention. Notably, this treaty established that trademark rights are territorial.

In 1932, Canada developed the Unfair Competition Act, which repealed most of the 1868 Trade Mark and Design Act. Most of the remaining provisions were related to industrial design rights. Nearly twenty years later, Canada developed a new legislation called the Trade-Marks Act, which repealed the remainder of the provisions related to the 1868 statute. The 1953 Trade-Marks Act established a public registry system for trademarks. More recent legislative changes are discussed in Chapter V of this book.

Clearly multiple distinct sources have influenced the history and development of Canadian IP regulation: UK statutes, Canadian statutes, international treaties, and international agreements. Although Canadian legislation, in its early stages, followed the British IP framework closely, it is not clear that Canadian legislation will follow this framework as closely in the future. European harmonization initiatives have brought major changes to the British legal framework that may not coincide very well with the Canadian approach. On the other hand, the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union may give the British legislative model renewed influence.

* * *