Main Body

II. Copyright

Anthony Rosborough and Lucie Guibault

A. Introduction

Copyright protects literary, dramatic, musical, artistic, and scientific works. Among the countless works protected by copyright law, one can think of the Beatles songs, the Star Wars movies, the Harry Potter book series, Microsoft Office Suite, World of Warcraft game, or Google Maps. But copyright does not protect only commercially successful works. Whether published or unpublished, popular or unpopular, beautiful or ugly, copyright protection arises as soon as an original work is created. Copyright is the sole right of the owner to authorize or prohibit the use of their works, save for the exceptions permitted by law.

While the first copyright law was adopted in England at the beginning of the 18th century, most modern copyright acts in the world were enacted around the turn of the 20th century. The protection granted remained relatively unchanged for decades, until technological developments (most notably computers and the internet) and international harmonization efforts required legislative amendments to be made. The cumulative result is a complex set of rules through which protection extends to a wider range of subject matter, with respect to broader exclusive rights, for a longer period of time. Among the new categories of subject matter covered by the Copyright Act, are performers’ performances, sound recordings and broadcast signals; the ensuing rights on these types of subject matter are known as ‘related’ or ‘neighbouring’ rights. It is important to note at the outset that no person is entitled to copyright otherwise than under and in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act, as it is interpreted by the courts.

This chapter provides a comprehensive overview of Canada’s copyright regime. Following a discussion on the justifications, history, international and national development in this introductory section, the chapter describes in detail the various components of the copyright protection, e.g. the concept of protectable subject matter, making the distinction between works of authorship and other subject matter (B.), the requirements for protection (C.), the concepts of authorship and ownership (D.), economic rights (E.), moral rights (F.), fair dealing and other exceptions (G.), and technological protection measures and rights management information (H.). The last section (I.) shortly discusses the role and functioning of collective rights management organizations, as well as that of the Copyright Board of Canada.

1. Copyright Theory

Why does copyright law exist at all? Theorists and policy makers have pondered on this question in myriad ways, finding influence from numerous theories and philosophical traditions. In surveying the theories and justifications presented in the General Introduction to this book, consider the following two examples of human creativity and expression in weighing the purpose and merits of the copyright system:

Example 1: “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue?”, Barnett Newman (1967)

Between 1966 and 1970, abstract artist Barnett Newman painted four large paintings using large rectangular sections of red, yellow and blue. The paintings were created without an intended goal or end result. The only objective on the part of Newman was for the result to be asymmetrical. The pieces in this series are held in separate collections, including the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

The above image is of the first of Newman’s works in this series, “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue I”.

The above image is of the first of Newman’s works in this series, “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue I”.

Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue is widely recognised as a pivotal piece of abstract art. Some art historians have remarked that the work constitutes a comment on prior abstract paintings that was highly critical of the movement’s predecessors. One artistic aim thought to be touted by Newman at the time of the work’s creation was to confront viewers with a bold arrangement of colour in way that embodies power and security. This was understood as a departure from prior abstract artists who utilised much more subdued colours and shapes in their works.

According to Wikimedia Commons, this image is now part of the public domain. However, see below the section on the idea/expression dichotomy for an explanation of why this may not be the case.

Despite these rather sophisticated observations of art historians and commentators, one can question the degree to which the protection of such works is consistent with the purposes and objectives of copyright protection. After all, their authors utilise relatively common elements of simple colours and shapes. Yet, despite the potential contention that this work may lack originality, it is protected by copyright as an artistic work. It is worth contrasting this dynamic with the following example below.

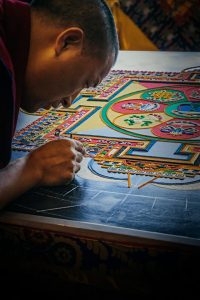

Example 2: Sand Mandala

In the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, monks ritualistically create a type of painting made from coloured sand. Mandalas are incredibly time intensive projects with a spiritual significance, featuring highly detailed patterns. Often mandalas can take multiple individuals several weeks to complete. The sand is applied using myriad small tools to achieve the desired patterns.

Ritualistically, mandalas are dismantled and destroyed after their completion. The destruction of mandalas is intended to symbolise the Buddhist doctrinal belief in the transitory nature of material life. Upon dismantling the mandalas, the sand is collected in jars which are wrapped in silk, transported to a body of water, and released back into nature. The release and redistribution of the sand from the mandala is intended to symbolise the temporary nature of life and the world.

Despite the significant degree of time, effort, creativity, and the cultural and religious importance of mandalas to those who create them, they are not protected by copyright. Photographs taken of mandalas or other forms of media which permanently fix the mandala in some tangible form will attract copyright protection, however, the transitory nature of these art pieces preclude copyright protection. In the section on fixation in copyright law, the reasons for why mandalas are generally not protected by copyright is further elaborated upon.

The differential treatment given to Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue and sand mandalas by the copyright system may seem arbitrary, and to some readers, unfair. Why is it that seemingly simple arrangement of colours can attract protection while an incredibly labour-intensive, culturally significant, and creative exercise would not?

The answer to this question is found in both the theoretical justifications for copyright (see the General Introduction chapter for a further discussion of these theories) as well as its objectives. These two aspects of copyright are not entirely distinct. The theoretical lens through which we view the purpose of the copyright system informs its priorities, scope and limitations.

II. The Objectives of Canadian Copyright Law

One might find it surprising that the Act contains no explicit mention of the purposes or objectives of Canadian copyright law. To a large extent, this task has been left to the courts over the past several decades. Beyond relatively vague references to the importance of “protecting authors”, Canadian copyright policy had been left without clear direction until the so-called “trilogy” of Supreme Court of Canada cases decided between 2002 and 2004.

The three cases described in textboxes below illustrate the point repeatedly made by the Supreme Court that the Copyright Act seeks to establish a balance between promoting the public interest in the encouragement and dissemination of works of the arts and intellect and obtaining a just reward for the creator. Copyright protection should be such that it prevents someone other than the creator from appropriating whatever benefits may be generated through the exploitation of the rights on the work. On the other hand, the system must also enable public access to and dissemination of artistic and intellectual works, which enrich society and often provide users with the tools and inspiration to generate works of their own.

The first of the trilogy cases is

[30] The Copyright Act is usually presented as a balance between promoting the public interest in the encouragement and dissemination of works of the arts and intellect and obtaining a just reward for the creator (or, more accurately, to prevent someone other than the creator from appropriating whatever benefits may be generated)…

[31] The proper balance among these and other public policy objectives lies not only in recognizing the creator’s rights but in giving due weight to their limited nature. In crassly economic terms it would be as inefficient to overcompensate artists and authors for the right of reproduction as it would be self-defeating to undercompensate them. Once an authorized copy of a work is sold to a member of the public, it is generally for the purchaser, not the author, to determine what happens to it.

[32] Excessive control by holders of copyrights and other forms of intellectual property may unduly limit the ability of the public domain to incorporate and embellish creative innovation in the long-term interests of society as a whole, or create practical obstacles to proper utilization. This is reflected in the exceptions to copyright infringement enumerated in ss. 29 to 32.2, which seek to protect the public domain in traditional ways such as fair dealing for the purpose of criticism or review and to add new protections to reflect new technology, such as limited computer program reproduction and “ephemeral recordings” in connection with live performances.

From these few paragraphs, we detect a clear utilitarian underpinning to Canadian copyright law. On the one hand, the regime must strive to incentivise creativity and protect the works of those who choose to create. Incentives and rewards complement one another. On the other hand, these rights must be limited; it would be unfair that the author receive more than their just reward or necessary incentive. The enrichment of the public domain requires that copyright not be used to hinder future creative innovation and the long-term interests of society. The limit set in the Théberge case consisted in the Court’s refusal to find infringement of the reproduction right where no new copy of the work had been made. Reaching a different conclusion would have been for the Court the equivalent of over-compensating the author for their creative activity.

CCH Canadian Ltd. v Law Society of Upper Canada, 2004 SCC 13

The second of the trilogy cases was CCH. This is one of the most widely-cited cases in Canadian copyright law. Students will undoubtedly become familiar with it for its articulation of the fair dealing framework in significant detail. The case involved facts familiar to many law students. The Great Library as Osgoode Hall in Toronto offered a request-based photocopy service where library visitors could obtain copies of various legal materials. In relying on their copyright, the publisher CCH launched an action against the Law Society of Upper Canada for infringement. The dispute eventually made its way to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The SCC’s decision is noteworthy for many different reasons. When it comes to the purposes and objectives of Canadian copyright law, the Court continued down the path laid by

[23] As mentioned, in Théberge, this Court stated that the purpose of copyright law was to balance the public interest in promoting the encouragement and dissemination of works of the arts and intellect and obtaining a just reward for the creator. When courts adopt a standard of originality requiring only that something be more than a mere copy or that someone simply show industriousness to ground copyright in a work, they tip the scale in favour of the author’s or creator’s rights, at the loss of society’s interest in maintaining a robust public domain that could help foster future creative innovation. By way of contrast, when an author must exercise skill and judgment to ground originality in a work, there is a safeguard against the author being overcompensated for his or her work. This helps ensure that there is room for the public domain to flourish as others are able to produce new works by building on the ideas and information contained in the works of others. [emphasis added; sources omitted]

[24] Requiring that an original work be the product of an exercise of skill and judgment is a workable yet fair standard. The “sweat of the brow” approach to originality is too low a standard. It shifts the balance of copyright protection too far in favour of the owner’s rights, and fails to allow copyright to protect the public’s interest in maximizing the production and dissemination of intellectual works. On the other hand, the creativity standard of originality is too high. A creativity standard implies that something must be novel or non-obvious — concepts more properly associated with patent law than copyright law. By way of contrast, a standard requiring the exercise of skill and judgment in the production of a work avoids these difficulties and provides a workable and appropriate standard for copyright protection that is consistent with the policy objectives of the Copyright Act.

(…)

[48] Before reviewing the scope of the fair dealing exception under the Copyright Act, it is important to clarify some general considerations about exceptions to copyright infringement. Procedurally, a defendant is required to prove that his or her dealing with a work has been fair; however, the fair dealing exception is perhaps more properly understood as an integral part of the Copyright Act than simply a defence. Any act falling within the fair dealing exception will not be an infringement of copyright. The fair dealing exception, like other exceptions in the Copyright Act, is a user’s right. In order to maintain the proper balance between the rights of a copyright owner and users’ interests, it must not be interpreted restrictively. As Professor Vaver, supra, has explained, at p. 171: “User rights are not just loopholes. Both owner rights and user rights should therefore be given the fair and balanced reading that befits remedial legislation.”

Reiterating the need to reach a balance between the public interest in promoting the encouragement and dissemination of works of the arts and intellect and obtaining a just reward for the creator, the Court discussed two of the essential components of the balance’s equation: the concept of originality and the fair dealing defence.

With respect to the first component, the Court was careful, when determining the standard of protection, not to allow rights owners to claim protection over non-original subject matter, as this would have a detrimental effect on future creators. With respect to the second component, the Court in CCH made a very bold and consequential statement that echoed far beyond the Canadian boundaries: nowhere else in the world has a court ever made a comparable declaration calling exceptions in the Copyright Act to be a user’s right. The importance of this statement cannot be overestimated: declaring exceptions to be users’ rights implies that these rights are not subservient to the copyright owners’ rights and that both rights (the owner’s and the user’s) must be analysed on equal footing. Only then can the copyright regime’s balance between disseminating works and obtaining a just reward for the creator be truly achieved.

Canadian Ass’n of Internet Providers v. Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada, 2004 SCC 45

The final case of the Trilogy is SOCAN v CAIP. At issue in this case was the liability of internet service providers (“ISPs”) for storing copyright protected materials on their servers. On a technical level, when users share or distribute infringing copies of copyright works online, ISPs incidentally store and provide access to these materials on their servers. This fact was the basis for a dispute launched by SOCAN, alleging that ISPs should pay royalties to SOCAN’s members for these reproductions.

The primary focus of the dispute was the “intermediary exception” at section 2.4(1)(b) of the Act which shields ISPs in these types of circumstances. This exception was intended to apply to intermediaries like ISPs who merely relay protected materials rather than store them on their own servers. This prompted the Supreme Court of Canada to both interpret the intermediary exception as well as comment more broadly on the purposes and objectives of Canadian copyright law.

In its decision, the Court found that the caching of the protected copies did not change the nature of the exception. ISPs were to be shielded for liability and not considered parties to infringing communications held on their networks. What is important for better understanding the purposes and objectives of Canadian copyright law is why the Court took this approach. Writing for the Court, Justice Binnie made it clear that this reasoning was based largely in an economic analysis:

“[92] Section 2.4(1)(b) of the Copyright Act provides that participants in a telecommunication who only provide “the means of telecommunication necessary” are deemed not to be communicators. The provision is not a loophole but is an important element of the balance struck by the statutory copyright scheme… In this context, the word “necessary” is satisfied if the means are reasonably useful and proper to achieve the benefits of enhanced economy and efficiency. The “means” include all software connection equipment, connectivity services, hosting and other facilities and services without which such communication would not occur. So long as an Internet intermediary does not itself engage in acts that relate to the content of the communication, but confines itself to providing “a conduit” for information communicated by others, then it will fall within s. 2.4(1)(b). The attributes of such a “conduit” include a lack of actual knowledge of the infringing contents, and the impracticality (both technical and economic) of monitoring the vast amount of material moving through the Internet…”

By interpreting the exception in the context of economy and efficiency, the Court clarified an important aspect about Canadian copyright law. In the end, the law is not there to protect authors or copyright owners at all costs. The law is there, largely to incentivise creation for the public benefit. Protection is part of that larger objective, but it is far from the primary or overarching purpose of the law.

The Trilogy of cases, with CCH as the beacon, has long stood as a key source of determining the purposes and objectives of Canadian copyright law. The Supreme Court does not hesitate to reiterate these principles whenever the occasion arises, such as in Keatley Surveying Ltd v Teranet .

Keatley Surveying Ltd v Teranet Inc., 2019 SCC 43

The Province of Ontario operates a land registry which offers survey plans for access and download. The registry is operated by Teranet Inc. Keatley Surveying is a surveying company that sought to bring a class action against Teranet for reproducing survey plans in the registry. The common issue between the parties was whether the survey plans were protected by Crown copyright under section 12 of the Act.

The dispute served as an opportunity for the Supreme Court of Canada to provide an update on the purposes and objectives of Canadian copyright law. Justice Abella, writing for the majority, writes:

[44] This Court’s post-Théberge jurisprudence has sought to calibrate the appropriate balance between creators’ rights and users’ rights. This balance infused the Court’s treatment of fair dealing in CCH, for example, where McLachlin C.J. noted that “the fair dealing exception is perhaps more properly understood as an integral part of the Copyright Act than simply a defence . . . . The fair dealing exception, like other exceptions in the Copyright Act, is a user’s right”…

[45] In Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada v. Bell Canada, 2012 SCC 36, [2012] 2 S.C.R. 326(SOCAN), and Alberta (Education) v. Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), 2012 SCC 37, [2012] 2 S.C.R. 345, the Court confirmed that fair dealing — and users’ rights — are to be given a large and liberal interpretation. In SOCAN, the Court emphasized the vital role played by users’ rights in promoting the public interest. The ability to access and use “works” within the meaning of the Copyright Act, are “central to developing a robustly cultured and intellectual public domain”…

[46] Fair dealing is, of course, only one component of Canada’s copyright law. It is, however, an emblematic one as it presents a clear snapshot of the general approach to copyright law in Canada — an approach which balances the rights of creators of works and their users…

Justice Abella’s summary of the law’s development is telling. It shows that since the early intimations of the balance to be struck in Canadian copyright law from the trilogy cases, a complementary framework of rights and principles has developed. These are user rights. This is a recognition that a robust public domain does not happen by accident. It requires careful nourishing and protection from the law, and this too is part of the purposes and objectives of Canadian copyright law.

III. History and International Harmonisation of Copyright

a. History

As alluded to above, Canadian copyright law derives primarily from English copyright law, which in turn owes its development to the introduction of the printing press to England in the late 15th century. With the increase in the use of printing presses, authorities in the United Kingdom sought to control the publication of books by granting printers a near monopoly on publishing in England. This was one of the earliest examples of technological advancement resulting in the progressive development of copyright laws. It led to the UK Licensing Act of 1662. It did not aim to protect publishers, let alone authors, but rather to ensure a certain government censorship over the publications in circulation. The Licensing Act established a register of licensed books to be administered by the Stationers’ Company, a type of guild, which consisted of a group of printers with the authority to censor publications. The 1662 Act expired in 1695, leading to a relaxation of government censorship, and in 1710 Parliament enacted the Statute of Anne to address the concerns of English booksellers and printers. By moving beyond mere censorship and into a regime of property rights, the Statute of Anne is widely credited for being the earliest iteration of modern copyright legislation.

The Statute of Anne established the longstanding copyright principles of authors’ ownership of copyright and a fixed term of protection of copyrighted works. It provided for a fourteen-year term of protection, and renewable for fourteen more if the author was alive upon expiration of the initial term. By imposing these measures, the Statute of Anne prevented a monopoly on the part of the booksellers. In limiting the term of copyright, the Statute also created a “public domain” for literature. The Statute also ensured that once a published work was purchased, the copyright owner no longer had control over its use or sale to a third party. This latter tenet of copyright policy would later become known as the principle of “exhaustion”.

As foundational as the Statute of Anne was for the overall development of copyright law, some key dimensions of modern copyright laws had not yet coalesced. While the Statute did provide for an author’s copyright, the benefit of this right was minimal because in order to be paid for a work, an author had to first assign it to a bookseller or publisher. As such, the first iteration of copyright law envisioned by the Statute of Anne placed publishers in an influential and essential position in the overall framework of rights. To use an analogy to real property law, the rights envisioned by the Statute of Anne were occasioned by significant restraints on alienation.

b. International Harmonisation

Despite the existence of numerous multilateral and bilateral agreements affecting the development of copyright around the world, the implementation and enforcement of copyright protection remains a matter of national jurisdiction. As a corollary, no creative or artistic work is capable of automatic “international protection”. Rather, copyright must be asserted by the rights holder in each relevant jurisdiction.

Nevertheless, international instruments have played a significant role in shaping standards of protection and the extent of rights under the copyright umbrella. Further, reforms to national legislation in Canada and in other countries have been influenced strongly by these developments at the international level. To better understand the relationship between international agreements and Canadian copyright law, key international instruments and their context are presented below:

Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (1886)

The Berne Convention was the first (and remains the most influential) multilateral agreement addressing copyright. As early as 1886, states such as Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, Switzerland agreed to a comprehensive framework which set basic standards of protection for copyright. The impetus for such an effort for copyright has much to do with history and trade at the time. This was an era marked by fierce nationalism and, among other things, the production and trade of translated books. To the dismay of many authors and publishers, translated books were often sold in foreign jurisdictions in the absence of any royalties or copyright. It was in this context that states got together to establish reciprocal protections and minimum standards of copyright protection.

The Berne Convention establishes the “Berne Union” of states, which agreed to collectively enact copyright laws that would ensure uniform and minimum standards of protection among its members. The main tenets established by the Berne Convention in this respect are threefold: The first is to establish a minimum term of protection for works, measured by the life of the (longest living) author (in case of joint authorship), plus fifty years after their death [Article 7]. The second is the prohibition on formal requirements for the recognition or exercise of copyrights [Article 5(2)]. In this sense, authors need not take any formal steps to receive copyright protection, such as registration or notification to allege ownership. Rather, copyright automatically vests upon creation of the work. The third is the principle of national treatment, whereby nationals of a Berne Union country receive in any other country of the Union the same protection as the nationals of those other jurisdictions are granted [Article 5(1)]. This ensures that infringements taking place in states other than the home jurisdiction of the copyright owner could be actionable and enforced in the state where the infringement takes place.

In addition to these three basic pillars of international copyright, the Berne Convention of 1971 foresees in a number of exceptions to copyright. The limitations listed are the result of serious compromise on the part of national delegations – between those that wished to extend user privileges and those that wished to keep them to a strict minimum – reached over a number of diplomatic conferences and revision exercises. Consequently, all but one limitation set out in the text of the Berne Convention are optional: except for the right to make quotations, countries of the Union are free to decide whether or not to implement them into their national legislation. One of the most important provisions introduced in the Convention during the Stockholm Revision Conference of 1967 is article 9(2), which establishes a “three-step-test” for the imposition of limitations on the reproduction right. According to this test, limitations must be confined to special cases, they must not conflict with normal exploitation of the protected subject-matter nor must they unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author.

Over many decades, the Berne Union has expanded far beyond the original handful of states to now include 178 members, consisting of the vast majority of states in the world. Reservations over its moral rights provisions and other issues prevented some countries, like the United States, from joining the Berne Union until long after it had been originally adopted, but as will be discussed in the context of TRIPS, most of these concerns have been alleviated. The Berne Convention has undergone amendments in the many years following its initial adoption, but it nevertheless remains the central authority for copyright protection at the international level.

The Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organizations, signed in Rome in 1961, was the first international legal instrument to recognize a minimum standard of protection for these categories of rights owners, namely performers, producers of phonograms and broadcasting organizations. However, the protection granted under this Convention is subsidiary to the protection of copyright in literary and artistic works. Consequently, no provision of this Convention may be interpreted as prejudicing such protection. The Rome Convention, like the Berne Convention, is based on the principle of national treatment.

Due to the position at the time that the rights of performers, phonogram producers and broadcasting organizations were subsidiary to the authors’ copyright, the rights recognized in this instrument are weaker than those laid down in the Berne Convention. In particular, performers pulled the short straw: they were only given the ‘possibility of preventing’ certain acts, which is certainly different to, and lesser than, the absolute ‘right to authorize or prohibit’ granted to phonogram producers and broadcasters. This made some jurists opine that the Rome Convention only grants performers’ a legal position, not a right. On the other hand, the Rome Convention was essential in ensuring performers and phonogram producers a right of equitable remuneration every time a phonogram published for commercial purposes, or a reproduction thereof, is used directly for broadcasting or for any communication to the public. This form of remuneration still accounts for a significant portion of the performers and sound recording producers income today.

Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (1994)

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPS”) was established through the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (“GATT”). The GATT is administered by the World Trade Organization. TRIPS addresses not only copyright, but all intellectual property rights. In relation to copyright, it does not replace the Berne Convention, but rather sits on top of it by requiring compliance with most of its substantive provisions (Articles 1-21). To alleviate the opposition to moral rights protection from the Untied States and other countries, TRIPS excludes the moral rights protection in the Berne Convention (Article 6bis) from its scope of application. TRIPS also requires the implementation of the Rome Convention of 1961.

The reason that TRIPS came about was primarily to address gaps in intellectual property enforcement as between states. While Berne required states to implement minimum standards of protection and offer protections to foreign nationals, it did not create a system of international enforcement per se. By relying on diplomacy and institutions of public international law alone to ensure compliance, the enforcement framework put in place by Berne required more effective “teeth”. States approached the solution to this problem initially by proposing a new framework administered by WIPO, but this eventually shifted to a system under the GATT framework and the international trade system. The thought behind this was that by treating intellectual property protections as the subject of international trade negotiations, states could then ensure that consistent levels of protection would be provided by WTO members.

In addition to affirming the protections from Berne (with the exception of moral rights protections), some of the key contributions from TRIPS are the following:

Most-Favoured Nation – [Article 7(8)] – The most-favoured nation principle is a cornerstone of bilateral trade and investment, and is prominent in the WTO system. In essence, the principle holds that any benefit or favourable treatment offered by one state to another must be offered to every other state. In this sense, the most-favoured nation principle precludes the existence of “special deals” or exceptions among WTO member states with respect to benefits that are offered to each other.

Idea/Expression Dichotomy – [Article 9(2)] – TRIPS codified the idea/expression dichotomy, whereby copyright applies to expressions but not ideas, procedures, methods of operation or mathematical concepts “as such”. This was left somewhat ambiguous in the Berne Convention, which did not directly address the extent to which ideas or processes could be protected. The Idea/Expression Dichotomy is further discussed in relation to the Subject Matter of Copyright.

Formal Protection for Computer Programs – [Article 10] – TRIPS also clarified that computer programs should be protected as literary works under the Berne Convention. This ensured that computer programs would be protected relatively equally among all WTO members and reflected the protection and enforcement concerns of the software industry.

With respect to copyright and related rights, the TRIPS Agreement introduced no new limitation, other than expanding the ‘three-step-test’ to all rights contained in the Berne Convention and to the rights contained in the TRIPS Agreement itself, such as the rental right.

Overall, TRIPS is the most significant intellectual property agreement because its ratification is required for membership in the WTO. The breadth of its membership based upon this requirement, coupled with its enforcement mechanism, renders it the most important multilateral agreement affecting copyright and intellectual property.

WIPO Copyright Treaty / WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty (1996)

In response to technological advancement in the 1980s and 1990s (largely digital technologies) the WIPO conducted negotiations among member states for the development of two new treaties, the World Copyright Treaty (“WCT”) and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty (the “WPPT”). These two treaties were negotiated and established jointly, and are often referred to as the WIPO “Internet Treaties”. The period in which these treaties came about was marked by a sudden realisation that the duplication and distribution of copyright-protected materials could be carried out by consumers at low cost. This decentralisation of the power of reproduction and distribution in the digital environment necessitated a revaluation of copyright protection globally.

The WCT reaffirmed the need to protect computer programs as literary works, along with databases as original selection and arrangement of information. The WCT’s most notable provision deals with the extra-layer of legal protection for technological protection measures (“TPMs”) and rights management information, the former of which are sometimes referred to as “digital locks”. Cumulatively, the overall objective of the WCT was to address the shortfall in copyright protection as it related to the newly (and quickly) evolving digital sphere. In some respects, these protections have remained impactful and significant. Having said that, the fact that the WCT predates the internet quickly rendered it wanting of further protections from the perspective of many rights holders.

Parallel to the WCT, the WPPT brought the protection afforded to the performer’s and sound recording producers‘ – “neighbouring” or “related” rights, into the internet age. The WPPT sought to create uniform protections for these types of rights to ensure their continued protection in the digital environment. It contains similar provisions to the WCT pertaining to the extra-layer of legal protection for technological protection measures (“TPMs”) and rights management information.

As was the case with the WTO/TRIPS Agreement, delegations to the WIPO Diplomatic Conference in December 1996 were unable to reach a consensus on the inclusion of any limitation on copyright and related rights, other than the so-called ‘three-step-test’. Article 10 of the WCT and Article 16 of the WPPT not only confirm the application of this test in the area of copyright – making it applicable to all authors’ rights and not only to the reproduction right – but extend it also to the area of neighbouring rights. The three-step test serves as a general restriction to all exemptions presently found, or to be introduced, in the national copyright and neighbouring rights laws. Even if an exemption falls within one of the enumerated categories of permitted exceptions, it is for the national legislatures (and, eventually, the courts) to determine on a case-by-case basis whether the general criteria of the three-step test are met.

The Marrakesh Treaty establishes a system of exceptions aimed at facilitating the production and most of all, the cross-border exchanges, of accessible formats and editions of copyright-protected works for persons with visual impairments. The scope of the Treaty is therefore rather limited as it applies only to published and printed works, but it nevertheless clarifies and expands upon the conventional exceptions and limitations to copyright. In order to come into force, the Marrakesh Treaty required that twenty states send their instrument of ratification. Canada was the 20th state to do just that in June of 2016. In accordance with the Marrakesh Treaty, Canada made the necessary changes to its already longstanding exceptions to the benefit of persons with “perceptual disabilities”, so as to allow persons with print disability to access published works in accessible formats outside of Canada.

Regional and Bilateral Free Trade Agreements (“FTAs”)

Similar to TRIPS, Canada is a party to the NAFTA, CETA, CUSMA and CPTPP agreements that primarily deal with investment and trade, but that also include provisions governing IP. The primary purpose of these agreements is to encourage more investment and trade among the member countries by eliminating barriers on the trade of goods and services. These agreements have been developed with an eye to ensuring greater transparency, predictability, and protection for investors. Such treaties and agreements inevitably also ensure that parties who seek the benefits of beneficial trade deals adhere to standards of IP protection agreed to by all parties.

c. Canadian Legislative History

The early development of the Canadian copyright framework is described in the General Introduction. The chapter stopped at the 1924 Copyright Act mentioning that the numerous amendments brought to the Act in the subsequent decades were altogether not terribly significant. It was not until 1985, through larger legal and policy reform efforts in relation to the Charter, that Canada began to take a serious look at reforming its copyright system. By 1988, significant changes were implemented to the Copyright Act.

Key Modernising Changes to the Copyright Act as part of the 1988 reforms:

- definition and protection of “computer programs”;

- enhanced moral rights protections;

- the creation of the Copyright Board;

- increased criminal sanctions for infringement;

- an exhibition right for artistic works;

- measures to strengthen the collective administration of copyright;

- the abolition of compulsory licences for the recording of musical works (i.e., forced licensing upon payment of a fee);

- procedures for licensing works of unknown authorship.

The 1988 reform significantly expanded Canada’s copyright protection. Where the former framework addressed only a narrow class of works, the broadening of the types of works for protection, mechanisms for enforcement and collective administration facilitated new business models and markets for a variety of works.

First phase of reform

In January 1989, following the signing of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement, the Copyright Act was amended to require Canadian cable and satellite companies to pay for the re-transmission of works included in distant broadcast signals. The amendments also expanded the concept of “communication to the public” from broadcasting to include all forms of telecommunication. Further on this trajectory, the 1993 the passage of Bill C-88 further amended the Canadian Copyright Act with the objectives of: (1) redefining “musical work” to clarify that the Copyright Act covered both graphic and acoustic representations of music; and (2) to ensure that all transmitters–whether broadcasters, specialty or pay services, or cable systems–were liable for royalties.

Concurrent with these developments, the North American Free Trade Agreement (“NAFTA”) was signed in 1992 and on January 1, 1994, the Canadian government’s North American Free Trade Implementation Act came into force. The Implementation Act amended the Copyright Act to introduce a rental right for sound recordings and computer programs (a rental right permits copyright owners to authorize or prohibit the rental of their works). It also increased protection against the importation of infringing works (e.g. literary, musical, or dramatic works).

The influence of free trade agreements on copyright law in the early 1990s was not confined to the North American context. Accordingly, amendments in the World Trade Organization Agreement Implementation Act, which came into force on January 1, 1996, extended the copyright protection afforded by the Copyright Act to all World Trade Organization (WTO) countries. It also gave performers protection against bootleg audio recordings (an unauthorized recording of a live event) and unauthorized live transmissions of their performances.

Second phase of reform

In 1997, the Act was significantly amended through Bill-C32 and this period marked the second phase of major reforms. Many of the changes to the Act at this time were indicative of a media paradigm in which some of the most lucrative works were being sold on cassette tapes and CDs. In this vein, Bill C-32 introduced significant changes to the Act by expanding protections for musical works to include a rental right of the physical media on which the musical work is stored (i.e., a CD) and the introduction of a levy on the sale of blank tapes.

Bill C-32 also abolished the (then) longstanding principle of perpetual copyright in unpublished works in favour a reformed framework which included term limits and conditions for posthumous works. It also introduced compulsory royalties for performers and makers of sound recordings (i.e., studio musicians and recording engineers). Under the revised framework, these contributors were to be remunerated equitably upon the public performance or communication to the public of the sound recording. With respect to remedies and enforcement, the bill also introduced the statutory damages regime, and a number of new (but limited) exceptions to infringement.

Third phase of reform

The third phase of Canada’s copyright reform process is marked by a shift to the digital realm and the communication of works over the internet. Through a series of changes over nearly 10 years, the government introduced a number of changes to “modernize” the copyright system. In March of 2005 the Ministers of Industry and Canadian Heritage, on behalf of the Government of Canada, responded to the Interim Report on Copyright Reform by releasing a Government Statement on Proposals for Copyright Reform outlining the proposals for a new Bill to amend the Act. This was the beginning of a long journey toward reforms.

These efforts toward reform saw a number of successive bills dying on the order paper as the result of elections and parliamentary prorogation. This turned the larger efforts toward reforming copyright for the digital environment an even lengthier project. Finally, after a number of stalled attempts toward reform, the Government of Canada introduced and considered Bill C-11 in 2010-2011 (known as the Copyright Modernization Act). Bill C-11 passed the requisite House of Commons readings and received Royal Assent on June 29, 2012. Most of the provisions of Bill C-11 were brought into force on November 7, 2012. One of the major changes that came through these reforms was the protection for technological protection measures (“TPMs”), in ss. 41.1 and following of the Copyright Act, e.g. one of the amendments necessary to ensure that Canada meets its obligations under the WCT and WPPT.

B. Protectable Subject Matter

Mere information, facts, ideas and data fall outside the scope of copyright protection. Indeed, it is one of copyright law’s most basic tenets that only those forms of expression that meet the requirements for protection are eligible for copyright protection. Ideas are not protected, but original expressions of ideas are. In this sense, one could argue that the free flow of information is the rule, and copyright protection is the exception. Before analysing the requirements for protection in section C., this section explains what is protectable subject matter under the Copyright Act, opening with a few words on the idea/expression dichotomy, before examining how the Copyright Act and the relevant case law define a ‘work of authorship’ (governed by Part I of the Act) or determine what qualifies as ‘other subject matter’ (governed by Part II of the Act).

Note that while it is conceptually important to understand the distinction between an idea and a form of expression, and to consider what types of subject matter are covered by the Act, this is not an exercise in which courts willingly engage. Too often the issue of the protectable subject matter is subsumed in the discussion of whether the ‘work’ meets the requirement for protection. It appears easier, and many times sufficient, to enquire if a work is original, rather than to first qualify the object of dispute from the lens of the protectable subject matter. This approach is not pure; it risks confusing key concepts, potentially leading to untenable outcomes. The consequence of overlooking this step may skew the copyright balance more to one side, most often to the rights owners’ side. For, an original idea is still just an idea and should not be protected, even if it is original.

I. Idea/Expression Dichotomy

Suppose you wanted to assert copyright in the following:

“[(23 – 14) + 43] x 2 = 104”

Would you be successful? The answer is no. This is because one of the cornerstones of copyright protection is that it does not extend to facts, ideas, schemes or methods. It is only when these concepts are arranged or expressed in a manner that is original that they can be protected. While it may be argued that the equation above is arranged in a way that is original (e.g., placement on the page, font, indenting/formatting), this argument is not likely to succeed.

The larger point is that ideas cannot be protected by copyright, only original expressions of them can be. Facts, methods or schemes belong in the public domain, because they do not originate from any author. They must remain in the public domain because they are the building blocks to further creation. Rather than query the extent to which a work is original, the idea/expression dichotomy delineates which things become “works” in the first place. The idea/expression dichotomy is not necessarily as binary as its name would suggest. Indeed, processes, methods, formulae and systems can be protected by copyright when they are expressed or designed in a manner that is original, as we shall see below.

Though the idea/expression dichotomy is a longstanding pillar of copyright law, it does not often form the basis for many copyright disputes. Nevertheless, in the 2013 decision of Nautical Data International Inc v C-Map USA Inc., the Federal Court of Appeal commented on the nature of the principle. Consider the case below:

Nautical Data International Inc v C-Map USA Inc., 2013 FCA 63

The Canadian Hydrographic Service (“CHS”) is part of the Department of Fisheries & Oceans Canada. It collects, assesses and publishes data in relation to Canada’s oceans and waterways, including marine charts, safety notices to mariners, tidal heights, currents and other navigational information. Traditionally, CHS has been the sole distributor of paper marine charts for navigational use. Since the advent of digital technology, CHS’ data has become increasingly attractive for third party software developers and manufacturers to use in their proprietary digital navigational equipment.

Nautical Data International (“NDI”) entered into an agreement with CHS for licensing is raw data to produce its own electronic charts. NDI then created electronic charts that were licenced to its end-users. Likewise, C-Map USA Inc. (“C-Map”) was also in the business of creating proprietary electronic marine charts for use in its navigational equipment. C-Map used the same raw data from CHS to produce its electronic charts, but without a licence. NDI brought an infringement claim against C-Map for its use of CHS’ data, but C-Map contended that NDI had no standing to enforce copyright in the data because it was not the exclusive licensee. At trial, the Federal Court found that NDI did not have standing to bring the claim. It found that though the licence allowed NDI to make use of data, it was not an exclusive licence and there is no copyright in information per se. Further, the inconsistency in the licence agreement between NDI and CHS left ambiguities regarding whether NDI had obtained the exclusive right to make digital copies of nautical maps or merely to use the information provided by CHS to create its own digital charts. Overall, the Federal Court found that there was no issue for trial and granted summary judgment to C-Map.

The proceeding made its way to the Federal Court of Appeal where the summary judgment was appealed by NDI. The essence of the dispute came down to whether the raw charting data provided by CHS could be the subject of copyright and therefore whether there was a serious issue to be tried.

At paragraph 14, Nadon and Sharlow J.J.A. write:

[14] NDI’s statements of claim allege that the Crown “owns” the CHS Data. That allegation presents the same ambiguity. If it is intended to mean that data can be owned in the same way as property can owned, then there is some question as to whether it is correct as a matter of law. Generally speaking, data — mere information — cannot be “owned” as though it were property. It can be kept confidential by its creator or the person who is in possession of it, and a legal obligation can be imposed on others by contract or by legislation to keep the information confidential. However, there is no principle of property law that would preclude anyone from making use of information displayed in a publicly available paper nautical chart, even if the information originated with the Crown or is maintained by the Crown.[Bolding added for emphasis]

Despite the Federal Court of Appeal’s clarification that mere information cannot be owned, it found that the trial judge should not have granted summary judgment on the basis that there were ambiguities left by the licence agreement. The Federal Court of Appeal held that there were open questions as to whether NDI was granted a licence only to use the information to make its digital charts or whether it was also granted the exclusive licence to make digital copies of nautical maps. As the maps themselves could be the subject of protection (where as the raw data could not) the determination of this question is crucial for resolving the matter. On this basis, the summary judgment motion was dismissed.

(Canada’s Copyright Act includes a regime for “Crown copyright”. This is discussed below).

Another case on point is the recent decision in Winkler v. Hendley, 2021 FC 498, in which the Federal Court discussed the difference between the depiction of nonfictional events and their use in an original publication.

Winkler v. Hendley, 2021 FC 498

[1] In the early morning of August 24, 1875, eight members of the notorious Donnelly family of Lucan, Ontario, armed with nothing more than clubs, won a pitched street battle against eighteen townspeople intent on revenge. Or did they? This and similar questions arise in this copyright infringement action because the plaintiffs assert the battle was the fictional creation of Thomas P. Kelley in his 1954 book The Black Donnellys. They claim Nate Hendley’s 2004 book The Black Donnellys: The Outrageous Tale of Canada’s Deadliest Feud infringes copyright in The Black Donnellys and its sequel, Vengeance of The Black Donnellys, including by copying Mr. Kelley’s fictional events, his creative embellishments of historical events, and his cinematic story-telling style.

[2] Mr. Hendley and his publisher, James Lorimer & Company Ltd, admit Mr. Hendley used Mr. Kelley’s books, among other sources, in doing research for his own book. But they argue Mr. Hendley’s book is an original literary work not copied from Mr. Kelley’s books or any other source. They also say Mr. Kelley’s The Black Donnellys is factual and argue that having represented it as a work of historical nonfiction, Mr. Kelley and his successors cannot now claim copyright in the persons and events described.

[3] I conclude there has been no copyright infringement.

[4] I agree with the defendants that an author who publishes what is said to be a nonfiction historical account cannot later claim the account is actually fictional to avoid the principle that there is no copyright in facts. Having presented the Donnellys’ street battle and other facts and events as a true historical account based on “unimpeachable sources,”

Mr. Kelley could not later assert that he was not to be taken at his word. His successors in title are in no better position and similarly cannot argue the facts were actually fictions and therefore subject to copyright protection.

(…)

[54] Copyright subsists whether an original literary work is one of fiction or nonfiction. The Copyright Act makes no distinction between the two. That said, copyright protection does not extend to facts or ideas

but to the original expression of ideas

. This does not mean that literary works on historical or factual subjects are less worthy of copyright protection. It simply means that copyright subsists in the particular means, method, and manner

in which those facts are presented in the work, rather than in the underlying facts themselves. This originality may include the structure, tone, theme, atmosphere and dialogue

used in presenting the facts.

Depending on the circumstances of each case, distinguishing a non-protectable idea, fact or data from an original expression of ideas can be relatively easy or very difficult. Nevertheless, the determination is essential in order to preserve the balance of interest in promoting the encouragement and dissemination of works of the arts and intellect and granting a just reward to the creator: over-protection would not only risk stifling further creativity, but it would also constitute an unjust reward to the creator.

II. Works of Authorship (Part I of the Act)

Despite the fact that neither ideas, facts, data or miscellaneous information receives protection, copyright law covers a vast array of different forms of expression. The types of “objects” that can be subject to copyright protection are wide ranging and subject to only a few limitations. Copyright protects “works” defined in general terms in section 5(1) of the Act, which states:

You may ask why the Act distinguishes between these types of works if ultimately these distinctions are not determinative of whether copyright can subsist in these creations. The answer to this question is found partly in the fact that the Act treats works differently due to market differences and attaches different rights to distinct categories of works. In other words, distinct business models have coalesced around the creation, production and exploitation of works based on their type. As we will see, the Act addresses this (partly) by offering protections, exceptions and limitations that are not always entirely uniform. Though it does not close the door on copyright protection for types of works that do not fit within these categories (e.g., video games), the need to tailor protections to specific markets and business models requires some level of legislative distinction. Therefore, the “types” of works under the Act, are sufficient conditions for copyright protection, but not necessary ones.

Literary Works

For the most part, the notion of literary works under copyright should be fairly intuitive. They are written works, whether in electronic or physical form. Literary works include not only substantial works of literature such as novels, books or articles, but also smaller written pieces such as emails, letters, pamphlets, poetry, forms, conference proceedings and databases.

literary work includes tables, computer programs, and compilations of literary works;

Literary works also include less obvious subject-matter. Most particularly, computer programs and software code are protected as literary works. In the 1980s and early 1990s, the prospect of protecting software as literary works under copyright law was not universally supported among the members of the Berne Union. The disagreement on this point stemmed largely from the fact that object code (the series of 0s and 1s) as opposed to the source code (the algorithm written in computer language) is primarily utilitarian in nature, and that the programs themselves are not sufficiently fixed to warrant protection. The 1994 TRIPS Agreement, together with the 1996 WIPO Copyright Treaty, ended this debate by requiring formal protection for computer programs as literary works. Despite the harmonisation of this protection among WIPO members, debates at the policy and academic level surrounding the efficacy of copyright protection for software and its implications continue to this day.

Dramatic Works

Like many aspects of the Act, the notion of a “dramatic work” is a term of art. It is not necessarily confined to those types of works which would be orchestrated as part of a High School Drama class. Rather, it includes a broad range of works which contain a scenic arrangement or an acting component, such as plays, operas and musicals (but not the music), screenplays, scripts, choreographic notation, choreographic shows and a cinematographic work. The Act defines a dramatic work as including:

(b) any cinematographic work, and

(c) any compilation of dramatic works;”

In addition, the Act defines a “choreographic work” as including:

Case Study: Alfonso Ribeiro v Take-Two Interactive Software Inc, et al., [2019]

The Fortnite “Fresh Dance” as captured within the video game in 2019.

Actor Alfonso Ribeiro is famous for playing the character “Carleton” on the 1990s television show The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. On the show, character Carleton became recognisable for his arm-swinging dance and penchant for Tom Jones. Ribeiro created the dance himself, crediting influences from Eddie Murphy’s “White Man Dance”, and Courteney Cox’s dancing in Bruce Springsteen’s “Dancing in the Dark” music video. Since its advent on the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, the Carleton Dance has become recognisable to many who grew up watching sitcoms in the 1990s.

Fortnite, a popular online video game released in 2017 by Epic Games, is a cooperative survival-shooter game. Players can play within a defined team, or individually. Fortnite allows players to purchase customisations for their characters that change their appearance in the game. Some of these customisations include the ability for players to direct their characters to perform brief dance sequences or gestures within the game so as to convey emotion. These character customisations or “in-game purchases” are extremely lucrative for video game developers and have the potential to generate substantial revenues.

One of the brief Fortnite dance sequences enabled by Epic Games, titled “Fresh Dance”, was modelled very closely on Ribeiro’s Carleton Dance. Seeing this, Ribeiro sought to register his copyright in the dance called ‘the Carleton’ with the U.S. Copyright Office. Ribeiro also launched a suit against Epic Games as well as the makers of NBA2K26 for similar use of the dance for copyright infringement. This required the U.S. Copyright Office to conduct a review of the Carleton Dance to determine whether it constitute a “choreographic work”. After a lengthy review, it concluded that the Carleton Dance was not choreography, but in fact a “simple dance routine”. The U.S. Copyright Office commented with the following:

“The dancer sways their hips as they step from side to side, while swinging their arms in an exaggerated manner… In the second dance step, the dancer takes two steps to each side while opening and closing their legs and their arms in unison. In the final step, the dancer’s feet are still and they lower one hand from above their head to the middle of their chest while fluttering their fingers. The combination of these three dance steps in a simple routine that is not registrable as a choreographic work.”

Though Ribeiro’s copyright claim is rooted in United States law, the question it raises in relation to the protection of choreographic works is worth considering. In light of the paucity of case law in Canada on the interpretation of choreographic works, the case Pastor (c.o.b. Cuban Dance Entertainment (Caricas Cubanas)) v Chen [2002] BCJ No 1123 stands out. The British Columbia Provincial Court accepted that mere “moves” and “dance styles” (when containing sufficient elements of originality) can be properly covered by copyright. Nevertheless, we are left without a clear delineation between the notion of a simple routine and a choreographic work and Ribeiro’s case in the United States provides us with a factual scenario that poses questions for the law in Canada as well.

Artistic Works

Whereas each type of “work” under the Act may considered to be artistic in a literal sense, the notion of an “Artistic work” under copyright law is more conceptual than literal. Artistic works include creations, such as paintings, drawings, photographs and art prints. Perhaps less obvious things included under Artistic works are maps, plans, stage and costume designs and websites.

When discussing the notion of an “Artistic work”, it is important to emphasise that such works do not require an subjective analysis of artistic merit or quality. More accurately, whether a work is considered an Artistic work within the meaning of the Act will be assessed with reference to the creator’s intentions and the result of the finished work. For example in Evans and Hong v Upward Construction, 2017 BCPC 247, the British Columbia Provincial Court was tasked with deciding over copyright in a home renovation design and whether it could be considered an “Artistic work”. In addressing the issue of whether aesthetic quality must be assessed in order to rise to the level of an artistic work, the Court wrote at paragraph 14 that “…[n]o minimal degree of creativity is required for work to be original, nor does it need to display particular artistic quality. It is enough that it is a product of the author’s or designer’s skill and judgment”. The overall point is that the notion of an “Artistic work” does not augment the basic assessment for copyright originality — a non-trivial exercise of skill and judgment is all that is required.

Musical Works

The Act defines a musical work as:

III. Other subject matter (Part II of the Act)

Performer’s Performance

Singers, musicians, actors, comedians all qualify as performers under the Copyright Act. As in the case of works of authorship, the Act defines what the object of protection is, e.g. a performer’s performance, rather than the person benefiting from the protection:

performer’s performance means any of the following when done by a performer;

(a) a performance of an artistic work, dramatic work or musical work, whether or not the work was previously fixed in any material form, and whether or not the work’s term of copyright protection under this Act has expired,

(b) a recitation or reading of a literary work, whether or not the work’s term of copyright protection under this Act has expired, or

(c) an improvisation of a dramatic work, musical work or literary work, whether or not the improvised work is based on a pre-existing work;

FWS Joint Sports Claimants v. Canada (Copyright Board), 1991 CanLII 8292 (FCA)

Key to the notion of a “sound recording” is the notion of a “maker”, which the Act defines as:

The Act further clarifies these “arrangements” at section 2.11, which provides:

The Act does not require that these sounds be musical or have any specific meaning: any type of sound could form the basis for this right. They can be things such as soundscapes, sound effects, nature recordings, sampling compilations, audio books, narrations, audio language lessons, and similar recordings. There is no other requirement for protection of sound recordings under the Act than the mere act of creating an actual recording.

The ‘arrangements’ referred to in section 2.11 usually refer to producers and those who provide contractual or financial assistance in order to bring the recording about. By ‘arrangements’ the above definition is not referring to the concept of a musical arrangement or composition, but rather the agreements, contracts or other circumstances that bring about the recording of the sounds. Given the ubiquity of audio recording equipment on personal electronic devices, it is equally possible that a “maker” could be a person with a smartphone audio recorder (depending on the circumstances). In this vein, the maker of a sound recording is not necessarily the author in the same way that a painter is the author of an artistic work. The role of a maker of a sound recording is conceptually different in that he or she need not necessarily create the sound being recorded.

Observe that soundtracks of cinematographic works, where they accompany the cinematographic works, are excluded from the definition of sound recording. The rationale is that ownership and exercise of rights on soundtracks must follow the main work, e.g. the cinematographic work. Only where the music is released as a separate sound recording, independent from the cinematographic work, will it benefit from protection as a sound recording as illustrated in the Re:Sound v Motion Picture Theatre Associations of Canada case.

Re:Sound v. Motion Picture Theatre Associations of Canada, 2012 SCC 38

[1] This appeal concerns the interpretation of the definition of “sound recording” in s. 2 of the Copyright Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-42 (“Act”), and specifically, the interpretation of the undefined term “soundtrack” used in that definition. The Act provides that performers and makers of sound recordings are entitled to remuneration for the performance in public or the communication to the public by telecommunication of their published sound recordings, except for retransmissions. Ultimately, the question this Court must answer is whether the broadcasting of sound recordings incorporated into the soundtrack of a cinematographic work can be subject to a tariff under the Act or whether such broadcasts are excluded by virtue of the definition of “sound recording” in s. 2.

[2] The appellant, Re:Sound, argues that the word “soundtrack” as used in s. 2 refers only to the aggregate of sounds accompanying a cinematographic work and not to the soundtrack’s constituent parts. In its view, since pre-existing sound recordings incorporated into a soundtrack are constituent parts of the soundtrack and not the aggregate of sounds accompanying the work, they do not fall within the scope of the word “soundtrack” as used in s. 2.

[3] For the reasons that follow, the appeal must be dismissed. A proper application of the principles of statutory interpretation leads to the conclusion that the appellant’s argument is untenable.

(…)

[35] According to s. 2, a “sound recording” is a recording consisting of sounds, “but excludes any soundtrack of a cinematographic work where it accompanies the cinematographic work”. Therefore, a “soundtrack” is a “sound recording” except where it accompanies the motion picture. Otherwise, the exclusion would be superfluous.

[36] When it accompanies the motion picture, therefore, the recording of sounds that constitutes a soundtrack does not fall within the definition of “sound recording” and does not trigger the application of s. 19. A pre-existing sound recording is made up of recorded sounds. The Act does not specify that a pre-existing recording of “sounds” that accompanies a motion picture cannot be a “soundtrack” within the meaning of s. 2. In my view, a pre-existing sound recording cannot be excluded from the meaning of “soundtrack” unless Parliament expressed an intention to do so in the Act. It could have done this by, for example, excluding only “the aggregate of sounds in a soundtrack”.

(…)

[39] … the word “accompanies” qualifies a soundtrack on a CD for remuneration under s. 19, whereas such a soundtrack would not otherwise attract remuneration under that section. It is difficult to imagine that the comment regarding “a soundtrack that is now available on a CD” might concern a CD containing “the entire collection of sounds accompanying the movie as a whole”, which is the interpretation of “soundtrack” the appellant urges this Court to adopt. If the appellant’s interpretation is correct, the CD in question would have to include not only the pre-existing recordings, but also all the dialogue, sound effects, ambient music and noises in the motion picture. It could not contain only the pre-existing sound recordings used in the movie.

Communication Signal

The broadcaster is presumed to be the first owner of the copyright in its communication signals and this right crystallises upon the first broadcast of the signal [see section 24(c)]. This definition clearly excludes those who provide unlawful broadcasting or retransmit communication signals broadcast by others. These exclusions are intended to ensure that so-called “pirate” broadcasters cannot avail themselves of protection in their own communication signals. The definition of broadcaster expressly excludes undertakings that engage in the ‘retransmission of signals’, such as cable or satellite distributors, for the very good reason that these entities do not broadcast signals. There is therefore no communication signal to protect.

C. Requirements for Protection

As the last section demonstrates, a vast array of forms of expression are susceptible to benefit from copyright protection as works of authorship, but only if they meet the statutory requirements, discussed in this section. Not all expressions are copyrightable: they need to show a sufficient degree of originality (I.), be fixed on a tangible medium (II.) and originate from a Treaty Country (III.). Note that performer’s performances, sound recordings and communication signals need not be original or meet any other threshold of creativity in order to receive protection under Part II of the Act. Moreover, performer’s performances benefit from protection even if they are not fixed, as further explained in part E.II below. However, as discussed in section C.III. below, the points of attachment for the grant of related rights differ significantly from those of works of authorship.

I. Originality

Perhaps the most significant factor in determining the existence of copyright protection is the extent to which the work is original. Indeed, this is the cornerstone of copyright law and acts as the gatekeeper of what gets protected and what does not. The requirement of originality is mentioned in three subsections of the Copyright Act, namely in sections 2 and 5(1).

every original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic work includes every original production in the literary, scientific or artistic domain, whatever may be the mode or form of its expression, such as compilations, books, pamphlets and other writings, lectures, dramatic or dramatico-musical works, musical works, translations, illustrations, sketches and plastic works relative to geography, topography, architecture or science;

work includes the title thereof when such title is original and distinctive;

Conditions for subsistence of copyright

5 (1) Subject to this Act, copyright shall subsist in Canada, for the term hereinafter mentioned, in every original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic work if any one of the following conditions is met:

Originality is a term of art. It does not mean that the work must be completely and absolutely distinguishable from other works, nor does it require that the work be ‘novel’ in the same sense as patent law. Rather, copyright originality refers to the extent to which the work is the product of the author’s individual personality, judgment and efforts.

No international agreement defines the concept of originality. The precise legal standard for originality therefore varies across jurisdictions internationally and some distinctions can be drawn between civil law and common law systems. Broadly speaking, civil law systems in continental Europe have adopted an approach more consistent with the personality theory, wherein originality is assessed primarily with reference to an extension of the author’s personality. In the Anglo-American common law tradition, the trend has been to weigh the extent to which the author expended effort or labour in creating the work. This bifurcation of priorities evokes slightly different assessments in value when it comes to how works, or the products of creative effort, should be regarded within the copyright system. This also means that a work may be deemed sufficiently original to deserve protection in one country, but not in another. In countries like France and Germany, the threshold for originality is higher than in Canada, which means that obtaining protection in Canada is easier than in those countries.

The earliest iterations of Canada’s approach to originality mirrored almost exactly the United Kingdom’s assessment of the author’s “skill, judgment and labour”. While this doctrine remains influential, courts in Canada have since expanded upon the broader purposes of copyright, which have in turn influenced the assessment of originality more broadly.

CCH Canadian Ltd. v Law Society of Upper Canada [2004] 1 SCR 339

McLachlin C.J., set out the test for originality in Canadian copyright law:

[16] …For a work to be “original” within the meaning of the Copyright Act, it must be more than a mere copy of another work. At the same time, it need not be creative, in the sense of being novel or unique. What is required to attract copyright protection in the expression of an idea is an exercise of skill and judgment. By skill, I mean the use of one’s knowledge, developed aptitude or practised ability in producing the work. By judgment, I mean the use of one’s capacity for discernment or ability to form an opinion or evaluation by comparing different possible options in producing the work. This exercise of skill and judgment will necessarily involve intellectual effort. The exercise of skill and judgment required to produce the work must not be so trivial that it could be characterized as a purely mechanical exercise. For example, any skill and judgment that might be involved in simply changing the font of a work to produce “another” work would be too trivial to merit copyright protection as an “original” work.

[25] … I conclude that an “original” work under the Copyright Act is one that originates from an author and is not copied from another work. That alone, however, is not sufficient to find that something is original. In addition, an original work must be the product of an author’s exercise of skill and judgment. The exercise of skill and judgment required to produce the work must not be so trivial that it could be characterized as a purely mechanical exercise. While creative works will be definition be “original” and covered by copyright, creativity is not required to make a work “original”. [Emphasis added]

The test for originality as set out in CCH remains the standard test for originality under Canadian copyright law. The notion of a work being the product of an author’s “exercise of skill and judgement” is helpful, but it raises a number of questions as to what types of exercises could be included under this umbrella. Again, the test for copyright originality is not whether the work is novel or inventive, but rather whether the work is the original expression of its author (originating from the author and no one else). To this end, it is not fatal to copyright’s subsistence in a work that is largely derivative of other works, or uses common techniques. The assessment is much more focused on the manner in which the particular work came about. So long as sufficient labour and skill was expended by the author to bring about the work through an exercise which is ‘more than trivial’, even largely derivative works can be the subject of protection.

Despite the Supreme Court’s attempts in CCH to -ensure that originality is assessed primarily on an objective basis–looking to the circumstances under which a work comes about–there is nevertheless a lingering question regarding the extent to which courts should weigh the aesthetic or artistic value of works. Though the exercise of skill and judgment can be regarded in many respects as factual, it can indeed be strongly influenced by which types of skill, and which sort of judgment, is exercised by the author in creating the work. These considerations become more present when the work at issue possesses utilitarian aspects. See the below case study for a further discussion of this issue: