V. Trademarks and Passing Off

Lucie Guibault

A. Introduction

1. Legislative history

Trademark protection has a long history in Canada. It commenced prior to Confederation with the passage on May 19, 1860 by the Legislative Council and Assembly of Canada of An Act respecting Trade-Marks. That Act made it a misdemeanour to use the known and accustomed trademark, name, package or device of any manufacturer with intent to deceive, so as to induce the belief that the goods so marked were manufactured by the owner of the mark. Section 2 contained a definition of fraudulent use of trademarks, names, packages, or devices, as being a use identical with or so closely resembling another trademark as to be calculated to be taken for the true trade-mark by ordinary purchasers. Provision was also made for actions by the owner of a mark for damages.

Contrary to matters concerning ‘Patents of Invention and Discovery’ and ‘Copyrights’, the Constitution Act, 1867 is silent in respect of trademarks. Legislative competence in the area of trademarks and unfair competition can just as easily fall within the provincial power over ‘Property and Civil Rights’, pursuant to s.92(13) of the Constitution Act, 1867 or within Parliament’s power over ‘Trade and Commerce’ pursuant to s. 91(2). After Confederation, however, Parliament enacted the Act of 1868, entitled the Trade Mark and Design Act. Over time Parliament’s competence over trademarks has been discussed occasionally, but was never seriously contested. Trademark protection is generally seen as being intra vires the power of Parliament since it has the power to adopt general regulation of trade affecting the whole country.

This Act repealed the prior trademark legislation. It was periodically amended, until it was subsumed in the Unfair Competition Act, 1932. This Act was passed as an attempt to take a broader approach to acts of unfair competition. The Act proved unsuccessful: it had many contradictions, was difficult to interpret, and resulted in some unforeseen complications in jurisprudence. The Unfair Competition Act remained in force for just over twenty years, when it was replaced by the Trade Marks Act, 1953. For more than sixty years, the Trade-marks Act [r.s.c. 1985, c. P-4] remained relatively unchanged since its passage in 1953. During this period, the only international convention to which Canada was a party in the field of trademark law was the Paris Convention of 1883. It allowed Canada to maintain a number of particular features of its trademark registration system, some of which were inspired from the U.S. system, like the use-based registration.

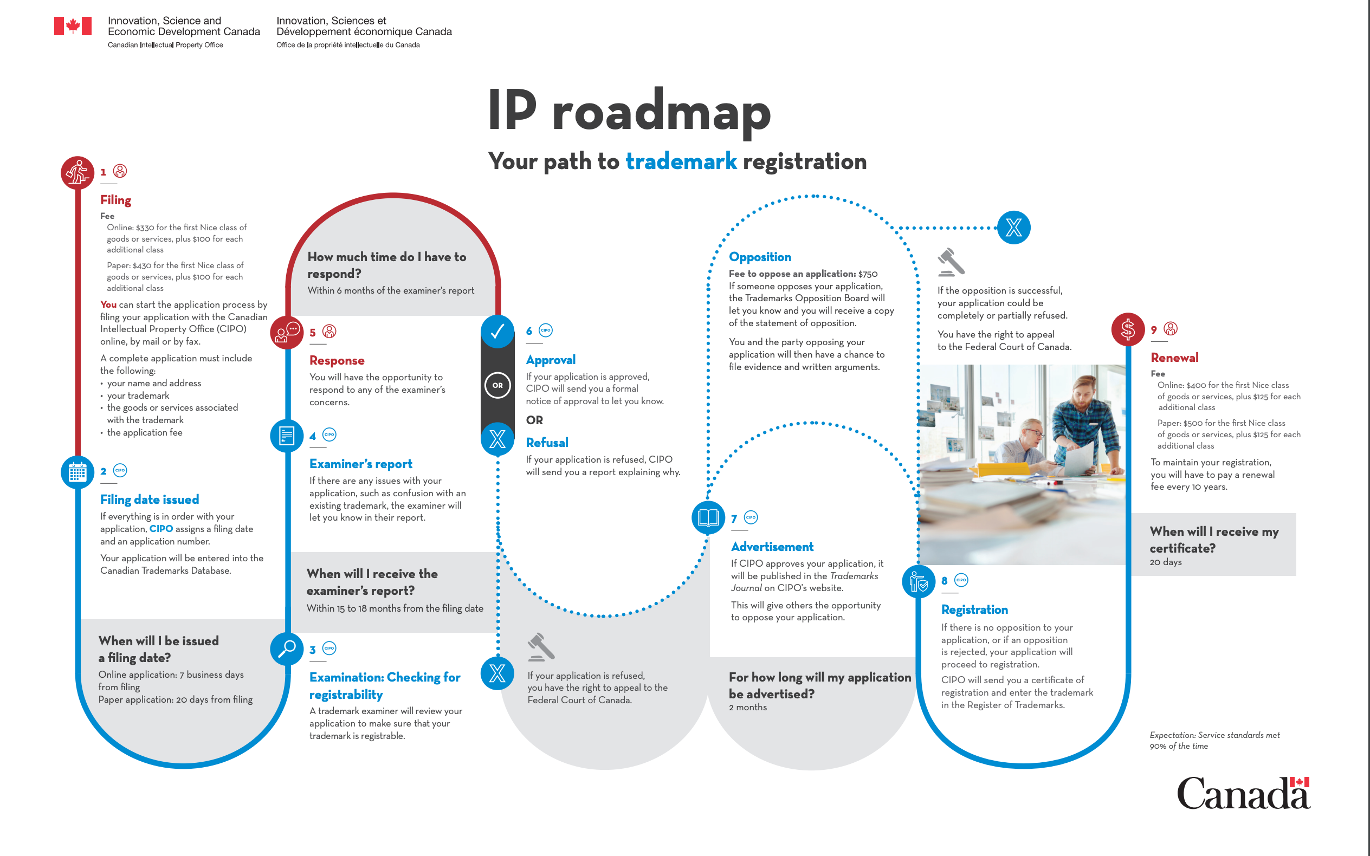

Starting in 2014, the Canadian government passed a flurries of amendments to the Trademarks Act. Some of these were rendered necessary as a consequence of Canada’s decision to (finally!) accede to international treaties in the area of trademark protection, while others were required as measures of implementation of the trade agreements signed with South Korea, the European Union, and the United States and Mexico. The changes brought about a major, long overdue, overhaul of Canadian trademark law. The acts amending the Trademarks Act are the following:

- Bill C-8 – Combating Counterfeit Products Act [S.C. 2014, c. 32, ss. 7-57]

- Bill C-31 – Economic Action Plan 2014 Act, No. 1 [S.C. 2014, c. 20, ss. 317-370]

-

Bill C-59 – Economic Action Plan 2015 Act, No. 1 [S.C. 2015, c. 36, ss. 66-72]

-

Bill C-30 – Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement Implementation Act, [S.C. 2017, c. 6, ss. 60-79]

- Bill C-79 – An Act to implement the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership [S.C. 2018, c. 23, ss. 17-18]

- Bill C-86 – Budget Implementation Act, 2018, No. 2 [S.C. 2018, c. 27, ss. 214-242]

- Bill C-4 – An Act to implement the Agreement between Canada, the United States of America and the United Mexican States [S.C. 2020, c. 1, ss. 108-110]

The most comprehensive modifications were brought through Bill C-31, The Economic Action Plan Act 2014, No. 1, and Bill C-30 aiming to implement Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). The revised Trademarks Act and Trademarks Regulations align Canadian trademark law with that of Canada’s major international trading partners including the United States and the European Union. In particular, under the new legislation, Canada adopted the standard procedures of the Singapore Treaty on the Law of Trademarks and the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks and ratified and implement the Madrid Protocol concerning the International Registration of Marks. Adhering to these internationally used conventions make is easier for Canadian businesses to protect their trademarks internationally and expand their businesses beyond Canada’s borders. Canadians are now able to file a single application and pay one set of fees to apply for protection in over 100 countries. Adoption of the standardised international procedures also make it easier for international companies to seek trademark protections for their businesses and marks in Canada, comparable to the mechanism put in place by the PCT in the area of patent protection. The Trademark Regulations have been modified accordingly. Both the Amended Act and the Regulations came into force on June 29, 2019.

Among the most outstanding changes are the broadening of the definition of ‘sign’ for what is considered eligible for trademark registration purposes, the possibility to obtain registration on proposed marks without having to prove the use of the mark, the shortening of the term of protection from 15 to 10 years, as well as the harmonised spelling of the word ‘trademark’ (which lost its hyphen).

2. Objectives of Trademark Protection

B. Registrable Signs

The recent legislative changes brought to the Trademarks Act have a direct impact on what is deemed eligible for trademark protection in Canada. The definition of ‘trademark’ was amended to now refer to only two categories of marks, e.g. the ‘ordinary’ trademark and the certification mark. This comes in sharp contrast to the previous versions of the Act that defined trademarks as including ‘ordinary’ marks, certification marks, distinguishing guises and proposed trademarks. In this section, we examine what is an eligible trademark, looking at the definition of ‘sign’, the requirement of distinctiveness, and the grounds for refusal of registration, before saying a few words about certification marks.

S. 2 trademark means

(a) a sign or combination of signs that is used or proposed to be used by a person for the purpose of distinguishing or so as to distinguish their goods or services from those of others, or

(b) a certification mark;

1. Definition of Sign

Until the recent legislative amendments, the Act did not specifically describe the sort of signs that could be registered as trademarks, except for a definition of ‘distinguishing guise’. These were understood as including “(a) a shaping of wares or their containers, or (b) a mode of wrapping or packaging wares, the appearance of which is used by a person for the purpose of distinguishing or so as to distinguish wares or services manufactured, sold, leased, hired or performed by him from those manufactured, sold, leased, hired or performed by others”. Typical signs that have always been deemed admissible as registrable trademarks encompass a word, a personal name, a design, a letter, a numeral, colours, a figurative element, a mode of packaging goods, and the positioning of a sign. In recognition of the changing marketing landscape, the evolving consumer habits, and the enhanced technical possibilities, the new definition of ‘sign’ in s. 2 of the Trademarks Act now also includes a range of less traditional signs, such as a three-dimensional shape, a hologram, a moving image, a sound, a scent, a taste, and a texture. With the broadening of the scope of eligible signs for trademark registration, the concept of ‘distinguishing guise’ was repealed from the Act, since it was no longer needed as separate concept.

2. Distinctiveness

(i) the three-dimensional shape of any of the goods specified in the application, or of an integral part or the packaging of any of those goods,

(ii) a mode of packaging goods,

(iii) a sound,

(iv) a scent,

(v) a taste,

(vi) a texture,

(vii) any other prescribed sign.

According to s.37(1)(d) TA, the Registrar shall refuse an application for the registration of a trademark if he is satisfied that the trademark is not distinctive. As Michele Ballagh explains (Trademark Legislation – 2019 Amendments, Hamilton Law Association, 2020), the sign must be “wholly without” or “bereft” of any distinctive character before the examiner should refuse the application or request evidence.

EXAMPLE # 1: SOUND MARK – 1733564

[Click on the link above to listen to the sound bite]

Registrant

Danjaq, LLC

11400 Olympic Blvd

Suite 1700

Los Angeles, CA 90064

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Goods

(1) Pre-recorded audio and video compact discs, DVDS, and motion picture films featuring entertainment, namely, action adventure, drama, comedy, and romance; musical sound recordings, contained on compact discs and digital music (downloadable) provided from web sites or from any other communications network including wireless and cable; computer video games; video and computer game compact discs adapted for use with television receivers; downloadable computer video game software supplied on-line from databases or provided through a global computer network or from any other communications network including wireless and cable; images and animations via the internet and wireless devices; downloadable videos and films featuring entertainment, namely, action adventure, drama, comedy, and romance via a wireless network for use with mobile devices; downloadable mobile telephone games and graphics via a global computer network and wireless devices.

Services

(1) Entertainment services, namely, production and distribution of motion pictures.

(2) Internet services, namely, providing information via an electronic global computer network in the field of entertainment relating to motion pictures, and providing electronic games, not downloadable, via the Internet.

Questions: Can this piece of music be used to distinguish the products and services of the company holding the trademark? What kind of extra evidence do you think was requested from this applicant by the Registrar of Trademarks? Would another IP right provide protection for this sign? What is the advantage for the company of registering a trademark on this sign?

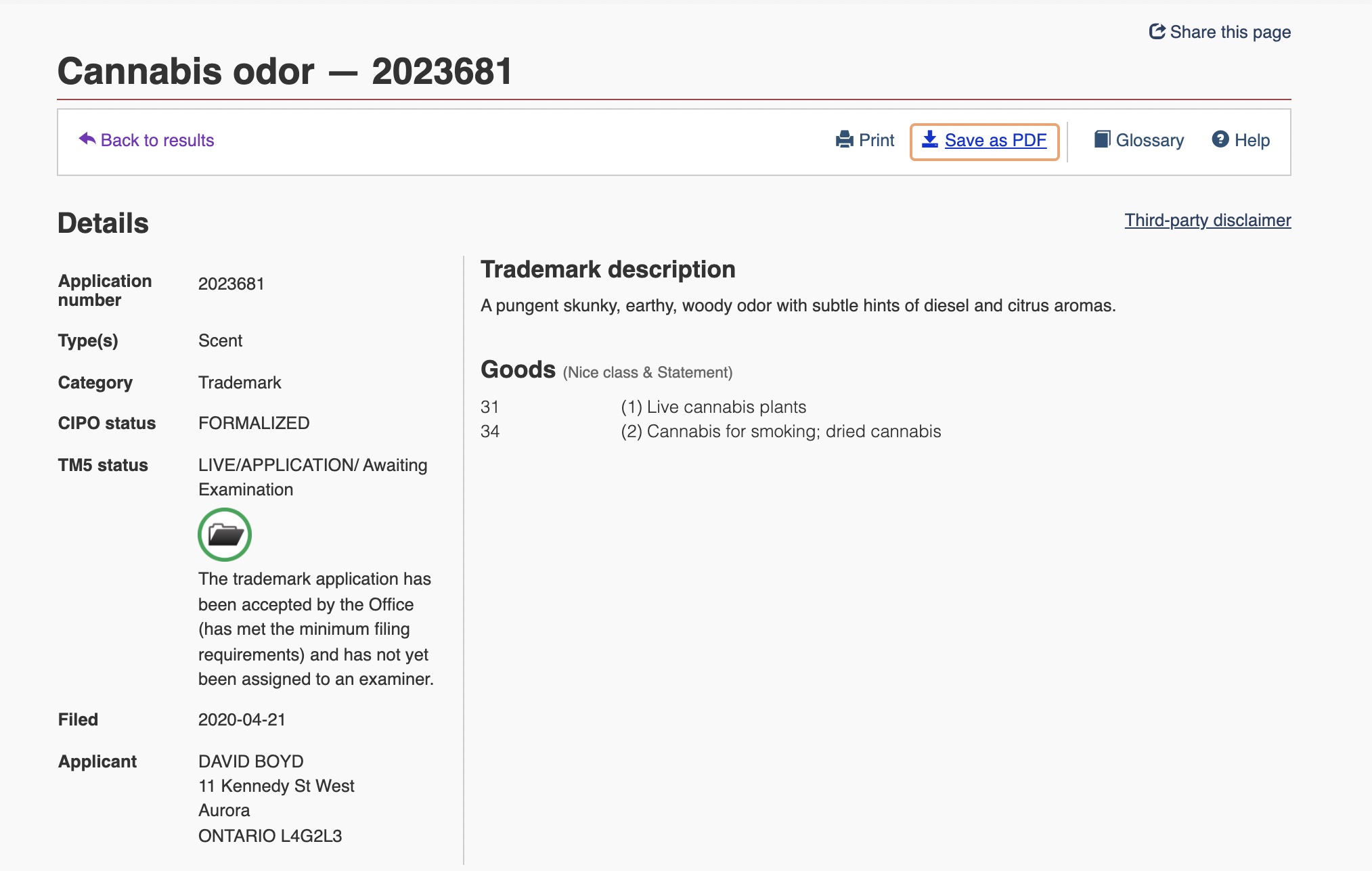

EXAMPLE # 2: A scent – Cannabis odor

Questions: Can the scent mark that is the object of this application be used to distinguish the product of this applicant from those of other producers? What kind of evidence could be adduced to support the registration of this trademark? How likely is it that the trademark would be registered?

NOTE: this trademark application is now listed as ‘withdrawn’ in the Trademark database.

2. When Trademark is [Not] Registrable

The Act not only defines what a registrable sign is and when a mark is distinctive, it also lays down the grounds for refusal to enter a trademark in the Register. The expression used in s. 12(1) TA ‘When Trademark is Registrable’ is somewhat misleading, since the opening sentence is formulated in the negative: ‘a sign is registrable if it is not…’ What ss. 12 (1) and (2) regulate are actually the grounds for refusal of registration against which the Trademark Office examines every single trademark application.

The most frequently invoked grounds for refusal relate to the descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive character of the trademark (s. 12(1)(b) TA) and the existence of a confusing trademark in the Register (s. 12(1)(c) TA). That a descriptive trademark not be registrable is logical, since it presumably is incapable of fulfilling the primary function of a trademark, e.g. distinguishing the goods or services of the company using it. The same logic applies to an already registered trademark that would be confusing with the trademark applied for: confusion among the public between two marks is an indication that either one or both marks are not able to distinguish the source of the goods or services. The concept of confusion is examined in detail in section F. below.

Section 12(2) TA prohibits the registration of a trademark where its features are dictated primarily by a utilitarian function. This ground for prohibition is not only connected to the requirement of distinctiveness as to the need to safeguard fair competition in the market: it would give an undue advantage to one company, above its competitors, to allow it to secure exclusive trademark rights on a functional aspect of a good. This principle is reinforced by s. 18.1 TA which provides that ‘the registration of a trademark may be expunged by the Federal Court on the application of any person interested if the Court decides that the registration is likely to unreasonably limit the development of any art or industry”.

In the course of the registration process, the unregistrable character of a trademark should be raised by the Registrar of Trademark as a matter of law. If it is not, a trademark that is not registrable can be attacked either at the stage of the opposition during the registration process, pursuant to s.38(2) TA, or as a defence to a trademark infringement claim, pursuant to s. 18(1)(a) TA.

When trademark registrable

12 (1) Subject to subsection (2), a trademark is registrable if it is not

(a) a word that is primarily merely the name or the surname of an individual who is living or has died within the preceding thirty years;

(b) whether depicted, written or sounded, either clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive in the English or French language of the character or quality of the goods or services in association with which it is used or proposed to be used or of the conditions of or the persons employed in their production or of their place of origin;

(c) the name in any language of any of the goods or services in connection with which it is used or proposed to be used;

(d) confusing with a registered trademark;

(e) a sign or combination of signs whose adoption is prohibited by section 9 or 10;

(f) a denomination the adoption of which is prohibited by section 10.1;

(g) – (h.1) in whole or in part a protected geographical indication identifying a wine, a spirit or an agricultural product or food where the trademark is to be registered in association with a wine not originating in a territory indicated by the geographical indication;

(…)

(i) subject to subsection 3(3) and paragraph 3(4)(a) of the Olympic and Paralympic Marks Act, a mark the adoption of which is prohibited by subsection 3(1) of that Act.

Utilitarian function

(2) A trademark is not registrable if, in relation to the goods or services in association with which it is used or proposed to be used, its features are dictated primarily by a utilitarian function.

Guiding principles have been established by jurisprudence to determine whether the mark is clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive of the services. The approach to take consists in recognizing:

(1) that whether a trademark is clearly descriptive is one of first impression;

(2) that the word “clearly” in para. 12(1)(b) of the Act is not a tautological use but it signifies a degree and is not synonymous with “accurate” but means in the context of the paragraph “easy to understand, self-evident or plain”, and

(3) that it is not a proper approach to the determination of whether a trademark is descriptive to carefully and critically analyse the words to ascertain if they have alternate implications when used in association with certain wares and to ascertain what those words in the context in which they are used would represent to the public at large, who will see those words and will form an opinion as to what those words will connote: see John Labatt Ltd. v. Carling Breweries Ltd. (1974), 18 C.P.R. (2d) 15 at p. 19.

The evaluation of the descriptive nature of the mark must take into account the goods and services in association with which the mark is used. For a trademark to be “deceptively” misdescriptive, it must mislead the public as to the character or quality of the associated goods or services. Evidence is key, as the three examples below demonstrate.

EXAMPLE # 1: Descriptive Mark – Orange Maison for Home Made Orange Juice

Home Juice Co. v. Orange Maison Ltée, [1970] S.C.R. 942

Since 1954 respondent has been selling orange juice in the Province of Quebec under the trade mark ORANGE MAISON and, since December 9, 1960, this trade mark has been registered at the Trade Marks Office. After objecting to an application for registration of the trade mark HOME JUICE filed by appellant Home Juice Company, respondent brought an action against the other two appellants claiming infringement of its own trade mark. Appellants then moved in the Exchequer Court to strike out the registration of respondent’s trade mark on the ground that it is clearly descriptive in the French language of the character or quality of the wares in association with which it is used.

(…)

In this Court, as in the Exchequer Court, the appellants in support of their contention as to the meaning of ORANGE MAISON relied especially on two dictionaries published in France in 1959: the Petit Larousse and the Robert. In both, the definition of the word “maison” used as an adjective is given as: [TRANSLATION] “that which has been made at home” and also [TRANSLATION] “of good quality”.

Respondent answered that this meaning is not found in dictionaries published in Canada, namely, the Bélisle and the Larousse Canadien Complet both published in 1954. In my view, this argument is not valid. Positive evidence drawn from the works of lexicographers who give a certain meaning is in no way destroyed by the fact that others do not report it. A work of this kind is never absolutely complete and negative evidence is always in itself weaker than positive evidence.

Respondent has contended that the current meaning in France is not to be considered, that regard must be had only to the meaning current in Canada and that, in the absence of any evidence, whether by dictionaries or otherwise, that the meaning in question was current in Canada at the date of registration, no account should be taken of a recent meaning found in France only. This contention would have serious consequences if it was accepted. One result would be that a shrewd trader could monopolize a new French expression by registering it as a trade mark as soon as it started being used in France or in another French-speaking country and before it could be shown to have begun being used in Canada.

In my opinion, the wording of s. 12 does not authorize such a distinction. It refers to a description “in the English or French languages”. Each of these two languages is international. When they are spoken of in common parlance they are considered in their entirety and not as including only the vocabulary in current use in this country, a vocabulary that is extremely difficult to define especially in these days when communication media are no longer confined within national boundaries. On this point, I should like to quote what Evershed J. said concerning the word “Oomph” in a case in which he held that “Oomphies” could not be considered as descriptive of the character or quality of shoes (In the Matter of an Application by La Marquise Footwear, Inc.:

I should perhaps add this: much argument was addressed upon the footing that, after all, the word, in so far as it is in current use, however short and brutish a life it may have, is American slang rather than, as we would say, part of our own native tongue. That is a matter upon which one might have debate for hours — whether it is the fact that the English tongue as spoken in these islands and the English tongue as spoken in the United States or in Canada or in Australia or in other parts of the globe is or is not one and the same language. I do not propose to throw any light upon any possible answer to the question, save to say that, where, as here, the word is primarily employed in the film industry, and, as is well known, the products of the American film industry, are shown and seen by hundreds of thousands of people throughout the whole of the English-speaking world, I think that it would be an affectation to say that a word which has gained any currency as an American slang word ought to be treated in these islands, in the absence of any evidence one way or the other, as a foreign word.

The trial judge seems to have considered it of great importance that respondent’s trade mark includes only the two words “ORANGE MAISON” while its wares are orange juice, not oranges. He quoted the following words of Lord MacNaghten in the Solio case:

…the word must be really an invented word; nothing short of invention will do. On the other hand, nothing more seems to be required. If it is … “new and freshly coined” (to adopt an old and familiar quotation), it seems to me that it is no objection that it may be traced to a foreign source, or that it may contain a covert and skilful allusion to the character or quality of the goods.

With respect, it must be emphasized that this was said of an invented word. Here, the trade mark is composed of two French words and this is not at all a case of a covert allusion but that of an explicit description indeed. The omission of the words “jus de” (juice) in no way prevents the word “ORANGE” from being descriptive of the character of the wares, because those words are clearly understood through the association with a liquid product. It must also be noted that respondent took care, in his application for registration, to disclaim any right to the exclusive use of the word “orange” by itself. It must therefore be said that the distinctive character of the trade mark is claimed exclusively for the combination “ORANGE MAISON”. But, as we have seen, the word “maison” thus placed clearly becomes an adjective descriptive of quality.

Therefore, when the meaning of the trademark is analyzed in respect of the goods to which it is affixed, the only possible conclusion is that the first word is an elliptical description of their character and the second an explicit description of their quality.

In Kirstein Sons & Co. v. Cohen Bros., this Court held that the trade marks “Shur-on” and “Sta-zon” were descriptive of the frames of eyeglasses to which they were affixed and considered them as mere corruptions of descriptive words. If the corruption of a word of the language does not destroy its descriptive character, why should an ellipse do it? This is what appears to have been held in Channell Co. v. Rombough where Mignault J. speaking for the majority in this Court said (at p. 604):

…a common English word having reference to the character and quality of the goods cannot be an apt or an appropriate instrument for distinguishing the goods of one trader from those of another. And the mere prefixing of the letter “O” to such a word as cedar certainly does not make it so distinctive that registration gives to the appellants the right to complain of the use of it by another manufacturer to describe a polish whereof oil of cedar is one of the ingredients.

It having been held that the word “cedar” should be considered as descriptive of a product that included only a small quantity of cedar oil, a fortiori the word “orange” should be considered as descriptive of “orange juice”.

For these reasons, I would allow the appeal with costs, set aside the judgment of the Exchequer Court, allow appellants’ motion without costs and order that the registration made for respondent in the Register of trade marks under number 120,375, on December 9, 1960, be amended by restricting it to the territorial area of the Province of Quebec.

EPILOGUE: The trademark Orange Maison was entered in the Trademarks Register, ORANGE MAISON — 0391939 on 23 September 1977 presumably based on the evidence of acquired distinctiveness (see below for explanation on this concept)

EXAMPLE # 2: Deceptively Misdescriptive Mark – Spirit of Cuba Rum produced in the Dominican Republic

Ron Matusalem & Matusa of Florida Inc. v. Havana Club Holding Inc., S.A., 2010 FC 786

1. The present appeal by Ron Matusalem & Matusa of Florida Inc. (the applicant) is made pursuant to section 56 of the Trade Marks Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. T-13 (the Act). It exclusively concerns the registrability of the trade-mark “THE SPIRIT OF CUBA” (the Mark), application number 1,154,259, based on proposed use in association with rum (the wares).

2. On October 2, 2009, the Trade-Marks Opposition Board (the Board) found that the Mark is deceptively misdescriptive and is not distinctive when used in association with rum and thus allowed the opposition made by Havana Club Holding Inc., S.A. (the respondent).

3. The applicant now invites the Court to overrule the Board’s decision, to reject the opposition and to grant the application to register the Mark in association with rum.

(…)

12. Paragraph 12(1)(b) of the Act provides that a trade-mark is registrable if it is not either “clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive” in the English or French language of the character or quality of the wares in association with which it is used or proposed to be used.

13. “Distinctiveness” is also a requirement to a valid trade-mark and means a trade-mark that “actually distinguishes” the wares in association with which it is used from the wares of others: see section 2 and paragraph 38(2)(d)of the Act.

14. The present litigation arises from the fact that the word “spirit” has two meanings, both of which are relevant to the wares. The first, the interpretation espoused by the applicant, means a mental condition or attitude; while the second, the interpretation espoused by the respondent, means strong, distilled liquor. There is evidence supporting both of these definitions.

15. When determining whether the Mark in its entirety is deceptively misdescriptive, the issue is whether the general public in Canada would be misled into the belief that the product with which the trade-mark is associated has its origin in the place of a geographic name contained in the trade-mark. One must place oneself in the position of the average Canadian consumer of ordinary intelligence and education who would see the Mark used in association with rum.

16. When determining whether the Mark is descriptive or misdescriptive, a decision maker should not carefully and critically analyze the words to ascertain if they have alternate implications in the abstract. Rather, a decision maker should apply common sense to determine the immediate impression created by the Mark as a whole in association with the wares. In short, the etymological meaning of the words is not necessarily the meaning of the words used as a trade-mark.

17. The Court finds that the Board’s decision is reasonable in the circumstances. Moreover, even if the matter would have to be reviewed de novo, the Court finds that the additional evidence submitted in this appeal would not justify overruling the result reached by the Board. The Mark, when viewed in its entirety, is deceptively misdescriptive of the place of origin of the wares and is not distinctive.

18. In the case at bar, the Board was faced with two contradictory interpretations of the words used in the Mark in relation to the product, here rum, with which the Mark is associated. The first was to interpret “spirit” as meaning “liquor” and “of Cuba” as meaning “from Cuba.” The second was to interpret “spirit” as meaning “soul” or “essence.”

19. The Board chose the first interpretation and held:

… we have a trade-mark comprising of two words: one that means alcoholic beverage and the second word being the name of a country known for its rum. I am of the view that the average Canadian consumer of rum confronted with the Mark used in association with rum is more likely, on a first impression, to think that it is rum originating from Cuba.

20. The Board also held, based on the same reasoning, that the Mark was not “distinctive”.

21. The findings made by the Board are not clearly wrong and were supported by the evidence on record and the public sources consulted. Moreover, an analysis of the additional evidence presented on appeal, while certainly relevant, demonstrates that it would not have materially affected the Board’s decision. In other words, in the Court’s opinion, this new evidence does not “put quite a different light on the record” before the Board (Mattel Inc. v. 3894207 Canada Inc., 2006 SCC 22, [2006] 1 S.C.R. 772 at paragraph 35) (Mattel).

22. The Mark appears on the label and is also embossed on the rum bottle. The applicant does not challenge the fact that the wares are manufactured in Dominican Republic and that Cuba is a producer of rum.

23. The applicant has argued both before the Board and the Court that the Mark, when viewed as a whole, “conveys the attitudes, temperament, disposition and character of the people of Cuba. It refers to the ‘soul’ or ‘essence’ of the applicants’ history in Cuba embodied in its rum products.”

24. According to the Salazar affidavit, the Salazar family has been making rum for a long time. In 1872, his great grandfather, Evaristo Alvarez, began producing rum in Santiago, Cuba under the name Matusalem (the “Matusalem rum”). The original recipe for Matusalem rum was developed in Cuba and uses the Solera system of blending liquor (which involves blending liquors of different ages to produce a final product of a certain average age). This same recipe and system are still used to make Matusalem rum.

Dr. Picard’s affidavit

29. The applicant relies on Dr. Picard’s affidavit where he expresses his opinion about the usage of the singular “spirit” in modern English. The survey conducted by Mr. Maurice Guertin also demonstrates that English-speaking Canadians, when faced with the word “spirit” in a variety of contexts, associate it with the soul, spirituality and the supernatural far more frequently than with alcohol. Finally, pertaining to the worldwide market, the Auclair affidavit reveals that there is not one specific country known for its rum, but rather an area called the Caribbean (or West Indies).

Mr. Guertin’s affidavit

35. With respect to the weight to be given to the internet survey conducted by Mr. Guertin, it is of very little assistance in this case. His survey asked two questions: (1) If you were to read the words “The Spirit” on a product, what would be the meaning of “The Spirit” for you? (2) If you were to read the words “The Spirit of Cuba” on a product, what would be the meaning of the “The Spirit” for you?

36. First, the Court doubts that it is “responsive to the point at issue” (Mattel, at paragraph 44) since it never puts the word “spirit” or “THE SPIRIT OF CUBA” in the context of rum. Again, the relevant question in the Court’s opinion is whether the average Canadian consumer of rum would believe that rum sold under the trade-mark “THE SPIRIT OF CUBA” comes from Cuba.

37. Second, the Court notes that only 506 people out of the 1,054 survey had purchased rum in the previous 12 months. Thus only 48% of those surveyed can be considered consumers of rum.

38. Third, the survey is not decisive. Even, when asked out of context, 15% of respondents associated “Alcohol/Drink” with the word “The Spirit” (first question), and 13% associated “Cuban Rum” with the words “The Spirit of Cuba” (second question). Thus, one may argue that on a first impression, a significant number of average Canadian consumers would believe that rum sold under the trade-mark “THE SPIRIT OF CUBA” comes from Cuba.

Ms. Auclair’s affidavit

39. Lastly, the Court finds that the evidence submitted by Ms. Auclair is not significant as it was either rejected by the Board or supports the Board’s factual findings.

EXAMPLE # 3: Utilitarian Function of a LEGO brick

Kirkbi AG v Ritvik Holdings Inc., 2005 SCC 65

1. For many years, Kirkbi AG (“Kirkbi”) has been a well-known and successful manufacturer of construction sets for children, and at times, for their parents too. The construction sets consist of standardized small plastic bricks, held together by a pattern of interlocking studs and tubes. Patent protection of this locking system has now expired in Canada and in several other countries. Kirkbi now attempts to protect its market share and goodwill against the inroads of competitors by invoking other forms of intellectual property rights. In particular, it is engaged in a long-running dispute with the respondent Mega Bloks Inc., formerly Ritvik Holdings Inc./Gestions Ritvik Inc. (“Ritvik”), a Canadian toy manufacturer. After the expiry of the last LEGO patents in Canada, the respondent began manufacturing and selling similar bricks, using the same locking method.

2. Kirkbi is now relying on an unregistered trade-mark, the “LEGO indicia”, which consists of the well-known geometrical pattern of raised studs on the top of the bricks as the basis for a claim of passing off under s. 7(b) of the Trade-marks Act (…)

3. Although I hold that s. 7(b) is a valid exercise of the federal power over trade and commerce, I agree that the action should be dismissed and that the majority judgment of the Federal Court of Appeal should be upheld. A purely functional design may not be the basis of a trade-mark, registered or unregistered. The tort of passing off is not made out. The law of passing off and of trade-marks may not be used to perpetuate monopoly rights enjoyed under now-expired patents. The market for these products is now open, free and competitive.

4. The LEGO toy business was founded in 1932. In 1949, Kirkbi produced its first toy building blocks. Those blocks were derived from a British product, the Kiddicraft blocks, which used a system of interlocking blocks. Kirkbi bought the patents covering the Kiddicraft system a few years later. Kirkbi then introduced significant improvements to the blocks. It added tubes underneath the blocks which coupled with the studs on top. This clever locking system increased the friction between the bricks and enhanced their “clutch power”, although children could still easily disassemble them. The current LEGO block was thus designed and marketed some 50 years ago. The same pattern of studs on the top of the block with tubes underneath remains in use. The only change was the addition of the mark “LEGO” on the top of each stud in tiny script. Kirkbi managed to keep patent protection of its technology in place for many years. But, in Canada, as elsewhere, patent protection came to an end. In Canada, the last patent expired in 1988. By that time, the quality and originality of its products had earned LEGO bricks a well-deserved reputation amongst parents and children. LEGO toys acquired generations of devoted clients and users in Canada as in many other countries.

5. After the expiry of Kirkbi’s patents, clouds gathered on the horizon. New competitors appeared and attempted to market similar if not identical products. The most aggressive was the respondent, a Montreal toy manufacturer now known as Ritvik. Ritvik had begun manufacturing toys in the 1960s. Later, in the 1980s, it developed and marketed a line of large-size building blocks. Finally, after the expiry of the last LEGO patents in Canada, it decided to use the traditional LEGO technology. It brought to market a line of small blocks, identical in size to LEGO blocks, which used the same geometrical pattern of stubs on top coupled with tubes underneath. They were sold under the name “MICRO MEGA BLOKS”. Ritvik sold its new line in Canada and exported them to several other countries. Over the last 10 years, it has become a significant global competitor to Kirkbi.

6. Facing new competition and now deprived of patent protection, Kirkbi attempted to protect its market position, employing a highly creative and aggressive use of the law of intellectual property and unfair competition, in several different legal systems throughout the world. This ongoing effort led to a substantial amount of litigation in several countries. For example, at times, Kirkbi tried to register its pattern of studs as a trade-mark or a design. Those attempts generally failed. In Canada, after the Registrar of Trade-marks rejected an application to register the pattern as a trade-mark, the appellant resorted to a more subtle and creative use of the resources of the law of intellectual property. This attempt led directly to the present litigation.

7. Kirkbi asserted unregistered trade-mark rights in respect of its use of the “LEGO indicia”. This mark consists of its distinctive orthogonal pattern of raised studs distributed on the top of each toy-building brick. These LEGO indicia are thus the upper surface of the block, with eight studs distributed in a regular geometric pattern (see Sexton J.A., (2003), [2004] 2 F.C.R. 241 (F.C.A.), at para. 11). It alleged that the marketing by Ritvik of its micro and mini lines of small bricks using the same pattern caused confusion with its unregistered trade-mark. It claimed relief under s. 7(b) of the Trade-marks Act and under the common law doctrine of passing off. In a statement of claim filed in the Federal Court, Trial Division, it claimed ownership of this unregistered mark and sought a declaration that it had been infringed. It requested a permanent injunction to prevent the marketing of the micro and mini lines of MEGA BLOKS and damages.

(…)

On the facts, the trial judge found that the LEGO indicia and the asserted unregistered mark were purely functional. The mark was the product (see Gibson J., at para. 61). Those findings were accepted by the Federal Court of Appeal and were not challenged in our Court. These findings raised the issue of the application of the doctrine of functionality, which barred the claim of infringement under s. 7(b) of the Trade-marks Act, in the view of the trial judge and of the majority of the Court of Appeal.

(3) The Doctrine of Functionality in Trade-marks Law

42. The doctrine of functionality appears to be a logical principle of trade-marks law. It reflects the purpose of a trade-mark, which is the protection of the distinctiveness of the product, not of a monopoly on the product. The Trade-marks Act explicitly adopts that doctrine …

43. In these few words, the Act clearly recognizes that it does not protect the utilitarian features of a distinguishing guise. In this manner, it acknowledges the existence and relevance of a doctrine of long standing in the law of trade-marks. This doctrine recognizes that trade-marks law is not intended to prevent the competitive use of utilitarian features of products, but that it fulfills a source-distinguishing function. This doctrine of functionality goes to the essence of what is a trade-mark.

44. In Canada, as in several other countries or regions of the world, this doctrine is a well-settled part of the law of trade-marks. In the law of intellectual property, it prevents abuses of monopoly positions in respect of products and processes. Once, for example, patents have expired, it discourages attempts to bring them back in another guise.

45. The doctrine of functionality is a well-established principle of the Canadian law of trade-marks. Indeed, our Court characterized it in 1964 as a “well-settled principle of law”:

The law appears to be well settled that if what is sought to be registered as a trade mark has a functional use or characteristic, it cannot be the subject of a trade mark. (Parke, Davis & Co. v. Empire Laboratories Ltd., [1964] S.C.R. 351, at p. 354, per Hall J.)

46. The Federal Court of Canada has consistently applied this doctrine. As in the present case, it has held time and again that no mark could consist of utilitarian features. Otherwise, it would make the wares a part of the mark and grant a monopoly on their functional features. For example, it is worth quoting MacGuigan J.A., in a discussion of the validity of a mark consisting of the particular shape of a razor head:

The distinguishing guise in the case at bar is in my opinion invalid as extending to the functional aspects of the Philip shaver. A mark which goes beyond distinguishing the wares of its owner to the functional structure of the wares themselves is transgressing the legitimate bounds of a trade mark. (Remington Rand Corp. v. Philips Electronics N.V. (1995), 64 C.P.R. (3d) 467 (F.C.A.), at p. 478; see also Pizza Pizza Ltd. v. Canada (Registrar of Trade Marks), [1989] 3 F.C. 379 (C.A.), at p. 381, per Pratte J.A.; Thomas & Betts, Ltd. v. Panduit Corp., [2000] 3 F.C. 3 (C.A.), at para. 25.)

This jurisprudence echoes earlier decisions of the Exchequer Court of Canada which applied the doctrine of functionality in respect of trade-marks, under an earlier statute. A combination of elements primarily designed to perform a function may not be the subject matter of a trade-mark (Imperial Tobacco Co. v. Canada (Registrar of Trade Marks), [1939] Ex. C.R. 141 (Can. Ex. Ct.), at p. 145; Elgin Handles Ltd. v. Welland Vale Manufacturing Co. (1964), 43 C.P.R. 20 (Can. Ex. Ct.), at p. 24).

47. The Canadian jurisprudence is consistent with legislative and jurisprudential developments in other countries. Some of these jurisprudential developments arose out of the ongoing campaign of Kirkbi to protect its market position in many countries, by other legal means after the expiry of its patents.

48. In the United States, Congress recently incorporated the doctrine of functionality into the law of trade-marks. It is now a part of the Lanham Trade-Mark Act: see 15 U.S.C.A. § 1052(e)(5). The Supreme Court of the United States has also held that purely functional features may not become the basis of trade-marks (see, for example, TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23 (U.S. Sup. Ct. 2001), at p. 34; Wal-Mart Stores Inc. v. Samara Bros. Inc., 529 U.S. 205 (U.S. Sup. Ct. 2000), at p. 211).

49. The European law of trade-marks also applies the doctrine of functionality. A directive of the European Commission does not allow the registration of purely functional trade-marks. It prohibits the registration as marks of signs which consist exclusively of a shape which is necessary to obtain a technical result (First Council Directive 89/104, Encyclopedia of European Community Law (EEC), art. 3(1)(e); see also L. Bently and B. Sherman, Intellectual Property Law (2nd ed. 2004), at pp. 794-96).

50. The European Court of Justice reached the same conclusion as had been reached in Canada. On the basis of the EEC directive and of the functionality principle, it found that the triangular shape of the Philips razor could not be registered as a trade-mark. It commented that the directive precluded the registration of shapes

whose essential characteristics perform a technical function with the result that the exclusivity inherent in the trade mark right would limit the possibility of competitors supplying a product incorporating such a function or at least limit their freedom of choice in regard to the technical solution they wish to adopt… (Case C-299/99, Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v. Remington Consumer Products Ltd., [2002] E.C.R. I-5475, at para. 79)

51. Kirkbi had registered its indicia as a community trade-mark, under European law. Seized of an application for cancellation by Ritvik, the Cancellation Division of the Office for Harmonization in the Internal Market (Trade-marks and Designs) applied the principles set out in Philips Electronics, and voided the mark (63 C 107029/1 “Lego brick” (3D), July 30, 2004). It found that it had a purely technical function and that the EEC directive barred its registration.

52. At the root of the functionality principle in European law, as in Canadian intellectual property law, lies a concern to avoid overextending monopoly rights on the products themselves and impeding competition, in respect of wares sharing the same technical characteristics. It is interesting to observe that, within two different legal systems, a judge of the English High Court and a French Court of Appeal raised the same concerns and came to similar conclusions, when they had to pass judgment on attempts by Kirkbi to protect its indicia by relying on trade-mark law, the tort of passing off or the delict of unfair competition in French law. In this manner, their judgments confirm the validity and broad relevance of the functionality principle as well as the doggedness of Kirkbi in its efforts to retain its market share by any means.

53. In the English case, Interlego AG’s Trade Mark Application, [1998] R.P.C. 69 (U.K. H.L.), INTERLEGO appealed the Registrar of Trade Marks’s refusal to register the LEGO indicia as marks under British trade mark law to the High Court. Neuberger J. dismissed the appeal on this issue. In his opinion, the functional features of the brick could not be a trade mark. Granting rights under trade-mark law would be tantamount to perpetuating a monopoly on the product itself:

In all the circumstances, it seems to me that Mr. Pumfrey was right to contend, that Interlego are not so much seeking to protect a mark on an item of commerce, but are attempting to protect the item of commerce as such. In other words, they are not so much seeking a permanent monopoly in their mark, but more a permanent monopoly in their bricks. This is, at least in general, contrary to principle and objectionable in practice. A trade mark is, after all, the mark which enables the public to identify the source or origin of the article so marked. The function of the trade mark legislation is not to enable the manufacturer of the article to have a monopoly in the article itself. In the present case there is no special reason to conclude that the general approach should not apply. On the contrary, the functional aspect of the knobs and tubes, and the extent of the monopoly in the field of toy building bricks when Interlego might establish if their appeal succeeded, are strong factors supporting the registrar’s decision. [p. 110]

54. During the same period, the appellant had also engaged in a variety of legal proceedings to ward off Ritvik’s entry into the French market. It relied on various grounds, but, in the end, it appears that its efforts foundered on the same grounds as in Great Britain, namely that, in a free market, trade-marks should not be used to prolong monopolies on technical characteristics of products. Competition between products using the same technical processes or solutions, once patent rights are out of the way, is not unfair competition. It is simply the way the economy and the market are supposed to work in modern liberal societies.

(…)

(4) The Applicability of the Doctrine of Functionality to Unregistered Trade-marks

56. Kirkbi does not challenge the application of the functionality doctrine to registered marks in this Court. It raises a different argument. It submits that the doctrine does not apply to unregistered marks. In its view, such a mark does not grant its holder monopoly rights, but solely the right to be protected against confusion as to the source of the product. Moreover, it argues that legislative changes which occurred at the adoption of the present Trade-marks Act changed the previous law and limited the application of the functionality principle to registered trade-marks.

57. The first prong of the appellant’s argument concerns the nature of the rights granted by an unregistered trade-mark. In substance, the appellant advances the submission that unregistered trade-marks do not create exclusive property rights, but give rise to a right to be protected against confusion in the market. The appellant says that this right could be enforced against competitors causing confusion in the market place under s. 7(b) of the Trade-marks Act and by the tort of passing off.

58. As Sexton J.A. found for the majority in the Court of Appeal, this argument has no basis in law. Registration does not change the nature of the mark; it grants more effective rights against third parties. Nevertheless, registered or not, marks share common legal attributes. They grant exclusive rights to the use of a distinctive designation or guise (Ciba-Geigy Canada Ltd. v. Apotex Inc., [1992] 3 S.C.R. 120 (S.C.C.), at p. 134; Gill and Jolliffe, at pp. 4-13 and 4-14). Indeed, the Trade-marks Act, by allowing for the assignment of unregistered trade-marks, recognizes the existence of goodwill created by these marks as well as the property interests in them. Registration just facilitates proof of title (Sexton J.A., at paras. 76, 77, and 81). Sexton J.A. rightly pointed out that the argument of Kirkbi appears to rest on a misreading of a 19th century judgment of the House of Lords, Singer Manufacturing Co. v. Loog (1882), (1882-83) L.R. 8 App. Cas. 15 (U.K. H.L.), aff’g (1880), 18 Ch. D. 395 (Eng. C.A.). This judgment stands only for the proposition that an unregistered trade-mark could be mentioned by competitors in comparative advertising, not that it failed to create exclusive rights to the name for the purpose of distinguishing the products. The functionality doctrine remains relevant, as the legal nature of the marks remains the same.

(…)

61. In the end, the appellant seems to complain about the existence of competition based on a product, which is now in the public domain. As “LEGO” and LEGO-style building blocks have come close to merging in the eyes of the public, it is not satisfied with distinctive packaging or names in the marketing operations of Ritvik. It seems that, in order to satisfy the appellant, the respondent would have to actively disclaim that it manufactures and sells LEGO bricks and that its wares are LEGO toys. The fact is, though, that the monopoly on the bricks is over, and MEGA BLOKS and LEGO bricks may be interchangeable in the bins of the playrooms of the nation – dragons, castles and knights may be designed with them, without any distinction. The marketing operations of Ritvik are legitimate and may not be challenged under s. 7(b). This is enough to dispose of the claim of the appellant, which had grounded its claim of passing off on the existence of a trade-mark. Nevertheless, given the discussion in the courts below, some comments on the common law action for passing off will be useful.

(…)

Conclusion

70. For these reasons, I would dismiss the appeal with costs

While no amount of use can remedy a sign that is dictated by a utilitarian function, the registration of a descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive mark is still possible provided that it has acquired secondary meaning in the market. To overcome the obstacle of s.12(1)(b) TA, a trademark owner must therefore show that it has acquired sufficient distinctiveness (otherwise known as ‘secondary meaning’) to let the mark fulfil its essential function. This possibility is specifically provided for in s.12(3) TA which states that ‘a trademark that is not registrable by reason of paragraph (1)(a) or (b) is registrable if it is distinctive at the filing date of an application for its registration, determined without taking into account subsection 34(1), having regard to all the circumstances of the case including the length of time during which it has been used.’ The ‘Bon Appétit Banff’ trademark of the Banff Lake Louise Tourism Bureau described in the frame below provides an example of such ‘acquired distinctiveness’.

EXTENSION: Acquired Distinctiveness of Bon Appétit

Advance Magazine Publishers, Inc. v. Banff Lake Louise Tourism Bureau, 2018 FC 108

1. The Banff Lake Louise Tourism Bureau (“Banff”) wanted to promote tourism during the “shoulder season”, the period after the end of the summer and before the launch of the ski season. It decided to advertise a ten-day event in November during which restaurants in the area would serve a series of special fixed-price meals, all under the name “Bon Appétit Banff”. It signed up local restaurants, set up a website, printed a number of advertisements, and required the participating restaurants to print menus and other material under the banner “Bon Appétit Banff”. It also applied for trademark protection for this name, and that application gave rise to this proceeding.

2. Advance Magazine Publishers, Inc. (“Advance”) opposed Banff’s application on the basis that it had already registered a number of trademarks under the name “Bon Appétit”, and allowing “Bon Appétit Banff” to be registered would likely be confusing for individuals in the marketplace. The Trademark Opposition Board (“TMOB”) granted Banff’s application, finding that the opponent had not filed evidence to support its claims, while Banff had filed evidence to demonstrate a limited use of the mark. Advance launched an appeal under section 56(1) of the Trade-Marks Act, and filed new evidence pursuant to s. 56(5) of the Act. Banff was given notice of this proceeding but did not participate.

3. The question in this appeal is whether an ordinary casual consumer, somewhat in a hurry, would look at a menu, notice or website advertising “Bon Appétit Banff” and likely be confused into thinking that the source of the services associated with the “Bon Appétit Banff” trademark was one and the same as the source of the goods or services associated with Advance’s BON APPÉTIT trademarks. If yes, Advance’s opposition to the registration of the Respondent’s trademark should be granted, and the TMOB decision should be overturned.

(registration No. TMA221520, registered June 24, 1977) For Publications, namely a magazine.

(registration No. TMA221520, registered June 24, 1977) For Publications, namely a magazine.

(Application number 1519424)

(Application number 1519424)

(1) Inherent and acquired distinctiveness

30. This factor requires consideration of both the inherent distinctiveness of the mark and the extent to which the mark has acquired distinctiveness through use in the marketplace. (…)

31. Inherent distinctiveness depends on the extent to which a trademark is an everyday word or a non-descriptive, distinctive word. Where a trademark is a unique or created name, such that it refers to only one thing, it will be inherently distinctive and given a wide scope of protection.

32. In contrast, a descriptive or suggestive word or phrase will be viewed as a weak mark and given relatively less protection; thus where a mark refers to many things or is a common reference in the market, or is merely descriptive of the goods or services, it will be given less protection.

33. The TMOB decision refers to the affidavit filed by Advance, which presented “dictionary definitions for the term ‘bon appétit.’ The literal meaning is ‘good appetite,’ however, the connotation is ‘enjoy your meal.’” On the basis of this, the TMOB found that the mark possesses “a fairly low degree of inherent distinctiveness as it is a common phrase comprised of two French words.” No other evidence on this point has been introduced, and I agree with the TMOB that the terms are not particularly unique. Indeed, they are often used at the opening of a meal.

34. Advance argues that the consideration of inherent distinctiveness must be made in the context of the particular goods or services (…). Advance contends that the term “bon appétit” is not inherently descriptive of the character or quality of the goods or services associated with its registrations and applications, namely on-line and print publications, operation of a website and social media activity, educational and training materials, etc.

35. I find that the terms are suggestive, but not particularly unique. They are two ordinary words, commonly associated with food or dining, but not unique or invented. However, there is no evidence that the term is commonly used in the market. I agree with the TMOB that the affidavit filed on this point did not establish that the term had become commonplace in the Canadian market. This does not end the analysis, however; I must consider the second aspect of this factor: whether the term has acquired distinctiveness.

36. On the evidence before me, Advance has established a strong presence in the Canadian market, both through long-standing distribution and sales of its print publication and through significant on-line and social media presence and activity. The affidavit of Ms. Wong Ortiz, on which there was no cross-examination, provides the factual foundation on this point which was missing before the TMOB.

37. The evidence on the reach into the Canadian market of the various components of Advance’s goods and services reflects wider trends over the past decade. While its print publication had ten-year total Canadian sales of 4.1 million copies to retailers and 1.36 million to customers, the annual figures show a decline in print sales over that period. The highest monthly totals in evidence are from 2006, when over 46,000 magazines were sold to retailers, of which over 22,000 were sold to customers. By 2015 this had declined to sales of over 22,000 magazines to retailers, of which 2,900 were sold to customers. In contrast, Advance’s on-line reach through its “Bon Appétit” website and social media presence has shown a steady and continuous growth in Canada during the same period. There are various ways of measuring this, but a few examples will make the point. Since 1997, there have been over 60 million “unique visits” to the website from Canada. As Ms. Wong Ortiz explains, “unique visitors” refers to different individuals annually and does not track repeat visits in any given year by the same unique visitor. Another approach simply measures the number of visitors per month from Canada, and this shows over two million unique visits per month from Canada.

38. In regard to social media, again there are a number of different ways of measuring the reach into the Canadian market through activity on social media. There are tens of thousands of Canadian “followers” of the Facebook and Twitter accounts held by Bon Appétit, and well over one million “likes” from Canadians for various articles and stories. Other channels measure the number of subscribers from Canada, and these show over ten thousand Canadian users, particularly focused on food, recipes, cooking, and restaurant recommendation features. It is estimated that 200,000 Canadians annually viewed videos presented by Bon Appétit on YouTube over the past decade.

39. In addition, Bon Appétit has licensed its trademark and logo in Canada to outlets such as the Home Shopping Network, Electrolux Major Appliances, and another (un-named) company that creates on-line travel packages. The trademark was also licenced to Terlato Wines International, a company that distributes wine through an on-line wine shop. In addition to wine sales, this company created promotional events, featuring gourmet meals and wines selected by renowned chefs.

40. In regard to the magazine and website, Ms. Wong Ortiz’ affidavit shows a number of feature articles on Canadian cities, with a particular focus on dining and other tourist attractions. This includes travel and restaurant guides for Montréal, Toronto, Québec City, Vancouver, and Niagara-on-the-Lake. Advertisements were placed in the magazine by several Canadian tourism bureaus, including Nova Scotia, Ontario, Québec, Tourism Canada, as well as tourism organizations from Toronto and Montreal. In addition, the magazine carried feature stories on particular culinary events held in various cities in North America. Overall, Bon Appétit’s main focus is on tourism, dining, specialty food and drink, food preparation, along with other tourist activities.

41. While there is no evidence of actual recognition in the marketplace by consumers, I find that it is reasonable to infer from the evidence referred to above that the Applicant’s use of “bon appétit” for its goods and services has acquired distinctiveness through its various activities in print and on-line, particularly given the evidence of sales and reach into the Canadian market. (…)

42. In many cases the acquired distinctiveness of a trademark is demonstrated by the reach of its presence in the market through both storefront presence and advertising. Consumer awareness can be demonstrated through surveys, or simply inferred from widespread advertising and the number of stores displaying the banner. Here, Advance sought to demonstrate its presence in the market through evidence of the sales of the magazine and the on-line presence through a website and social media vehicles. I find that the evidence of on-line and social media presence and activity is as useful and compelling as evidence of storefront presence and more traditional forms of advertising in print, radio or television.

43. In assessing customer awareness or reach into the marketplace through a website or social media presence, merely posting a website or putting content into a social media platform may not be indicative of any particular reach into the market which would support an argument of acquired distinctiveness through use in Canada. In this case, the more telling evidence relates to the number of visits or activity on the website or social media platforms. This is valuable because it demonstrates both Canadians’ awareness of the material and their desire to take some steps to seek it out, which itself reflects a certain recollection or awareness. The on-line impact of the brand is evident because it requires Canadians to take steps to engage, either through visiting the website or taking steps to “follow” it or to “like” a feature article or photograph on one or more social media platforms. This can be equally valuable in supporting an analysis of acquired distinctiveness under the Act.

44. On the basis of all of the evidence presented, I find that Advance has established that its BON APPÉTIT registered and applied-for marks have acquired a degree of distinctiveness in the Canadian market.

[NOTE: The trademark application filed by Banff Lake Louise Tourism Bureau for Bon Appétit Banff was refused]

3. Certification Marks

Not all marks are meant to distinguish the goods or services of one undertaking from those of another. Some marks, known as certification marks, typically apply to the goods or services manufactured, sold or supplied by various entities that meet the standards set by the association holding the mark. Think of CSA, CAA, Fair Trade, Energy Star, FSC, Egg Quality Assurance, Gluten Free, Canada Organic, Non GMO, Dairy Farmers of Canada, 100% Canadian Milk etc. These marks receive the same level of protection as traditional trademarks once they are registered. Certification marks are specifically regulated under ss. 2, 23 to 25 of the Trademarks Act.

2. certification mark means a sign or combination of signs that is used or proposed to be used for the purpose of distinguishing or so as to distinguish goods or services that are of a defined standard from those that are not of that defined standard, with respect to

(a) the character or quality of the goods or services,

(b) the working conditions under which the goods are produced or the services performed,

(c) the class of persons by whom the goods are produced or the services performed, or

(d) the area within which the goods are produced or the services performed;

Registration of certification marks

23 (1) A certification mark may be adopted and registered only by a person who is not engaged in the manufacture, sale, leasing or hiring of goods or the performance of services such as those in association with which the certification mark is used or proposed to be used.

Licence

(2) The owner of a certification mark may license others to use it in association with goods or services that meet the defined standard, and the use of the certification mark accordingly is deemed to be use by the owner.

That definition must be viewed in the context of the Act as a whole, in that, in order to be a valid mark, any certification mark must be:

- not clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive of the wares or services in association with which it is used;

- able to distinguish the wares or services of a defined standard from wares and services of others (ie. be distinctive);

- not be used by the certification mark owner, but only by authorized licensees, in association with the performance of services, the production of wares or advertising the wares or services of those licensees, at the date relied upon by the owner as a date of first use;

- not likely to be confusing with any registered or previously applied for trademark, or previously used trademark or trade name, in Canada (for a discussion of the concept of confusion, see section F. below);

- such that “use” must be in accordance with section 4 of the Act with respect to services, which requires that a trademark (and therefore certification mark) is deemed to be used with services if it is used or displayed in the performance or advertising of these services (for a discussion of the concept of use, see section E. below).

In relation to point 1 above, s.25 TA specifies that a certification mark that is descriptive of the place of origin of goods or services, and not confusing with any registered trademark, is registrable if the applicant is the administrative authority of a country, state, province or municipality that includes or forms part of the area indicated by the certification mark, or is a commercial association that has an office or representative in that area, but the owner of any certification mark registered under this section shall permit its use in association with any goods or services produced or performed in the area of which it is descriptive. In other words, there must be a connection between the description of origin of the goods or services offered and the location of administrative authority or commercial association carries on its affairs. Section 25 carves out a narrow exception to section 12(1)(b) for certification marks that are descriptive of a place of origin [see Maple Leaf Foods Inc v Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma, 2012 TMOB 249.]

Example: FAIR TRADE CERTIFIED & DESIGN — 1421478

Registration number

TMA801957

Type(s)

Design

Category

Certification Mark

CIPO status

REGISTERED

LIVE/REGISTRATION/Issued and Active

|

Filed

Registered Registration Expiry Date Registrant Fairtrade Canada Inc. Index headingsFAIR TRADE CERTIFIED

|

Goods(1) Body soap bars, deodorant soaps, lip balms, hand creams, shea butter. (2) Clothing for infants, namely, sleepwear; fresh flowers; green foliage accompanying fresh flowers in a bouquet. (3) Sports balls, namely, soccer balls, basketballs (4) Chocolate products, namely, chocolate chips, chocolate bars, cocoa powder; cereal-based bars; non-alcoholic beverage, namely, fruit juices; coffee; sugar; molasses; dried fruits. Certification mark textThe wares shall be produced, imported, processed and/or distributed in conformity with defined standards as set in the attached Trade Certification- Standard Operating Procedure manual and shall either be sourced from organizations of small producers or from establishments using hired workers. The organizations of small producers shall: be composed mainly of small producers; be able to demonstrate accountability to its members and for the resources used in its activities; use a portion of its income from the wares to invest in community initiatives for the improvement of social and economic conditions of its members; ensure the respect of national norms concerning the use and storage of pesticides; encourage its members to use environmentally sound methods of production; receive a set price or premium over the market price.The hired workers shall: receive minimum wages and benefit from safe and stable working conditions as defined by national legislation in the country of production; have the right and be given the opportunity to form a labour union; determine the use of the funds from the price premium associated with the sale of the wares through their elected representatives on a joint committee of workers and management representatives; use the funds for social and economic initiatives to improve their socio-economic initiatives to improve their socio-economic conditions. Where wares contain ingredients that cannot be coursed according to the above criteria, the wares shall: contain at least 20% Fair Trade Certified ingredients by dry weight; contain only Fair Trade Certified Ingredients where standards exist for those ingredients. AMENDMENT TO REGISTRATION / MODIFICATION A L’ENREGISTREMENT: |

The owner of a registered certification mark is responsible for certifying that the products bearing the mark have been produced, imported, processed and/or distributed in conformity with the standards set out in the defined certification standard. The owner’s licensees are required in their licenses to conform to the character and quality of the goods set out in the standard. The same obligation exists in relation to a certification mark for services. Failure to conform with the standard can lead to termination of the licensing agreement [see Robinson Sheppard Shapiro S.E.N.C.R.L./L.L.P. v Fairtrade Canada Inc., 2017 TMOB 133].

C. Prohibited Trademarks/ Official Marks

Apart from prohibiting the registration of signs that are descriptive, deceptively misdescriptive, confusing with a registered trademark or embodying a purely functional design, s.12(1) of the Act lists four additional categories of signs that cannot be registered: a sign or combination of signs whose adoption is prohibited by section 9 or 10; plant breeders’ rights denominations; geographical indications set out on a list maintained by the registrar; and a mark the adoption of which is prohibited under the Olympic and Paralympic Marks Act. The list of prohibited trademarks laid down in s.9 is quite impressive, ranging from ss.9(1)(a) to (o). Most prohibited marks listed in the section find their origin directly in Article 6ter of the Paris Convention of 1883. It makes sense that the international community would early on have made arrangements to protect one another’s state emblems, official hallmarks, as well as the emblems of Intergovernmental Organizations. Official mark can be put on the list of prohibited marks by filing a request with the registrar. Such requests may only be filed by countries who are parties to the Paris Convention, a province, a municipal corporation, Her Majesty’s forces, or any university.

Paris Convention 1883

Article 6ter

Marks: Prohibitions concerning State Emblems, Official Hallmarks, and Emblems of Intergovernmental Organizations

(1)

(a) The countries of the Union agree to refuse or to invalidate the registration, and to prohibit by appropriate measures the use, without authorization by the competent authorities, either as trademarks or as elements of trademarks, of armorial bearings, flags, and other State emblems, of the countries of the Union, official signs and hallmarks indicating control and warranty adopted by them, and any imitation from a heraldic point of view.

(b) The provisions of subparagraph (a), above, shall apply equally to armorial bearings, flags, other emblems, abbreviations, and names, of international intergovernmental organizations of which one or more countries of the Union are members, with the exception of armorial bearings, flags, other emblems, abbreviations, and names, that are already the subject of international agreements in force, intended to ensure their protection.

(…)

Compared to the legislation of other jurisdictions, however, the Canadian Trademarks Act contains two unique subsections: first with respect to any scandalous, obscene or immoral word or device (s. 9(1)(j)); and second, with respect to the use of any sign used by public authority in Canada (s. 9(1)(n)(iii)). Let us examine the two types of prohibited marks below, looking at signs used by public authorities first.

1. Official marks

This subsection in the Canadian Trademarks Act is undeniably its most unique and controversial feature. Because of the broad power it confers on public authorities over the use of their official marks and because of the relative ease of obtaining protection, the application of this provision has always carried an air of controversy. Some have argued for its repeal; most advocate for its narrow interpretation. As a result of the unabated criticism, s.9(1)(n)(iii) was modified in 2018 to create a mechanism aimed at reducing potential abuses in relation to official marks. Sub-paragraphs 9(3) and 9(4) give the Registrar the power, on its own initiative or at the request of anyone who pays the fee, to issue a public notice indicating that a previously issued notice that reserves the use of an official mark by a public authority no longer applies where the user of the official mark is not a public authority or where the authority no longer exists. The possibility to clean up deadwood in the Trademark Registry and to free some marks for others to use has been created; it must now be put to good use.

9 (1) No person shall adopt in connection with a business, as a trademark or otherwise, any mark consisting of, or so nearly resembling as to be likely to be mistaken for,

(n) any badge, crest, emblem or mark

(…)

(iii) adopted and used by any public authority, in Canada as an official mark for goods or services,

in respect of which the Registrar has, at the request of Her Majesty or of the university or public authority, as the case may be, given public notice of its adoption and use;

(…)

9 (3) For greater certainty, and despite any public notice of adoption and use given by the Registrar under paragraph (1)(n), subparagraph (1)(n)(iii) does not apply with respect to a badge, crest, emblem or mark if the entity that made the request for the public notice is not a public authority or no longer exists.[IN FORCE on 01.04.2025]

Notice of non-application

(4) In the circumstances set out in subsection (3), the Registrar may, on his or her own initiative or at the request of a person who pays a prescribed fee, give public notice that subparagraph (1)(n)(iii) does not apply with respect to the badge, crest, emblem or mark. [IN FORCE on 01.04.2025]

Despite the controversy, the application for a public notice recognizing a public authority’s official mark is a frequently invoked provision in the Trademarks Act. Protection of an official mark can be obtained by filing a request with the registrar. In determining whether a body is a public authority, three of the factors which may be taken into account are:

(1) does the body have a public duty;

(2) is the body subject to significant public control;

(3) and does the body direct its profits toward public benefit.

The degree of governmental control and the extent to which the body’s activities benefit the public appear to be the most important factors in determining whether a body is a public authority for the purpose of subparagraph 9(1)(n)(iii). Bodies that qualify as a public authority must also establish that the official mark that is the object of the notice has indeed been adopted and used prior to the filing of the request to the registrar. The registrar has no discretion to refuse, not even in cases where the public notice could be deemed not to be in the public interest. Contrary to normal trademarks, requests to have an official mark put on the list of prohibited marks are not subject to the same controls of ss.12(1)(a) to (d), i.e. they can be descriptive, deceptively misdescriptive, or even generic. The inscription of official marks on the register is not subject to the opposition proceeding, nor does the existence of a confusing or identical registered trademark prevent the publication of the notice.

Public notice is given through the Trademark Journal. The purpose of the registrar’s giving public notice of the adoption and use of an official mark is to alert the public to that adoption as an official mark by the public authority to prevent infringement of that official mark. It does not bestow upon the registrar any supervisory functions. Once public notice of the adoption and use of an official mark has been given, no person may adopt a trademark consisting of or so nearly resembling the trademark for which notice has been given as to be likely to be mistaken for it.

Defining ‘Public Authority’: Assn. of Architects (Ontario) v. Assn. of Architectural Technologists (Ontario), 2002 FCA 218

1 The Registrar of Trade-marks has given public notice that the Association of Architectural Technologists of Ontario (“AATO”) has adopted and used as official marks for services, the words ARCHITECTURAL TECHNICIAN, ARCHITECTE- TECHNICIEN, ARCHITECTURAL TECHNOLOGIST, ARCHITECTE-TECHNOLOGUE.

2 As a result, members of the appellant, the Ontario Association of Architects (“OAA”), may be prevented from using any of these words in connection with their professional services, unless they had started to use them before April 28, 1999, the date when the Registrar gave public notice in the Trade-marks Journal of their adoption and use by the AATO as official marks.

3 This is an appeal from a decision of the Trial Division in which the Applications Judge dismissed an application by the OAA to reverse the decision to give public notice of the adoption and use of the official marks. He held that the Registrar had committed no reviewable error in concluding that the AATO is a public authority and that it had adopted and used the marks as official marks for services. The decision is reported as Assn. of Architects (Ontario) v. Assn. of Architectural Technologists (Ontario) (2000), [2001] 1 F.C. 577 (Fed. T.D.).

4 There are important advantages for a body that is able to claim a mark as an official mark, rather than simply as a trade-mark. However, only a public authority may register an official mark under subparagraph 9(1)(n)(iii) of the Trade-marks Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. T-13. The principal issue in this appeal is whether the AATO, a self-regulatory professional body, is a public authority for the purpose of this provision and thus capable of requesting the Registrar to give public notice of its adoption and use of a mark as an official mark.