IV. Plant Breeders’ Rights

Sonja Gashus

A. Introduction

1. What is Plant Breeding?

The act of plant breeding is to intentionally manipulate a plant species to produce a plant variety with desirable characteristics.

What is a Plant Variety?

The term species is a familiar unit of botanical classification within the greater plant kingdom. However, it is clear that within a species there can be a wide range of different types of plants. Farmers and growers need plants with particular characteristics and that are adapted to their environment and their cultivation practices.

A plant variety represents a more precisely defined group of plants, selected from within a species, with a common set of characteristics.

Figure 1: Introduction to UPOV (multimedia presentation)

Plant breeding is conducted by breeders who use various techniques to create new varieties, including those of an agricultural and ornamental nature. Techniques used by plant breeders have developed significantly over time as a result of innovation and technological advancements. Ultimately, the goal of plant breeding is to improve existing plant varieties by breeding new varieties with more beneficial characteristics, such as improved yield, resistance to pests and other environmental factors, as well as varieties with desired aesthetical features.

Importance

Plant breeding is directly correlated to the needs of society. Plants help to feed the human population and can fuel industry and economic growth in developing countries. Developing plants with better performance better allow for such needs to be met.

The second of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals is to “[e]nd hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.” However, in 2019 the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimated in State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World publication that 690 million of the global population were undernourished and two billion people experienced hunger or did not have access to nutritious food. Coupled with continued population growth, a percentage of the population will not be provided with adequate food, one of the most basic human needs.

Improving plant varieties allow plants to be produced with a higher yield, longer lifespan, and greater tolerance to external factors, in addition to increased nutritiousness. By advancing plant performance in the growing process, accessibility of food is increased as a result of greater quantity and a lower cost of growing and for consumers. More efficient production of plants also may produce greater feed for animals, contributing to food supply.

Another major challenge to food production is climate change. Unstable climate conditions, more frequent and severe drought and flooding, as well as a higher pressure for insects and disease, present a difficult environment for growers and producers. With continuous and innovative plant breeding, the impact of climate change on the food supply can be mitigated as plant varieties can be bred to be more genetically tolerant or resistant to abiotic and biotic challenges.

In addition to agricultural food production, horticulture and ornamental plants are grown for the purpose of beautifying, decorating, and enhancing the environment. The ornamentals industry is distinct from agriculture and food production as these plants focus on aesthetic features such as flowers, leaves, or foliage and are bred to enhance such characteristics in addition to the common stress tolerance and yield. Ornamental plant varieties can include cut flowers, houseplants, trees, and shrubs, and are a keystone for indoor and outdoor gardening, design, and common green spaces in urban areas.

EXAMPLE: Tulip Varieties

Tulips, a part of the Tulipa species, are an extremely popular flower in the ornamental plant industry. Tulips are spring-blooming flowers that are usually large, showy, and bright, making them ideal for bouquets and gardens.

Through hybrids and cultivars, breeding programs have expanded the original Tulipa species (or known as botanical tulips in horticulture) into 15 divisions which include thousands of tulip varieties. Plant breeders continuously develop new varieties of tulips, as demand is constant for this decorative flower.

Figure 2: Homestratosphere, Popular Tulip Varieties Chart

Plant markets can play a crucial role in the health of developing nations. Farming is often the dominant provider of food, income, and employment in poorer countries. Improved plant varieties through plant breeding can also help fuel economies and further economic development. Enhanced efficiency allows farmers to produce a surplus of food for trade and exported goods with reduced costs of labour and higher amounts of production. According to UNCTAD, if intra-EU trade is excluded, developing countries’ imports and exports accounted for almost 60% of the global food trade in 2016 and is continuously trending upwards.

In addition to the agricultural plant market, the ornamental plant market accounts for a large portion of the economy in some developing nations, such as Brazil. The ornamental plant market is thriving, as there is high global demand among individuals and city planners who are constantly seeking out improvements to their decorative gardens and landscapes.

2. History of Plant Breeding

The effort to produce plants with beneficial characteristics such as improved quality, increased crop yield, tolerance of environmental pressures, and resistance to viruses, bacteria, insects, and fungi, has occurred since the beginning of agriculture. Since then, it has continued to develop over time.

Today, plant breeding can be accomplished through many different techniques that range from propagating plants with desirable characteristics to molecular techniques that make use of biotechnology and genetics.

Classical Plant Breeding

The most basic plant breeding technique is known as selective breeding (or artificial selection) and is performed by simply selecting plants with desirable characteristics for propagation. Selection exploits the naturally occurring variability of plants to discriminate against those with less desirable characteristics. A form of selection is cross-breeding, which is the deliberate interbreeding of closely or distantly related plant varieties to produce new varieties with desired properties within the same species. Selection is still practiced today by farmers in poorer countries, where instead of buying entirely new seeds, farmers save seeds from their best looking plants to use for the next season.

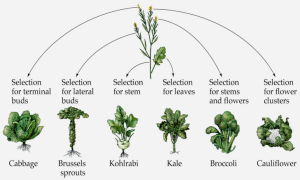

EXAMPLE: Brassica Oleracea

Brassica oleracea is a plant species that includes many common foods as cultivars, including cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts, collard greens, Savoy cabbage, kohlrabi, and gai lan.

Through artificial selection for various phenotype traits, the emergence of variations of the plant with drastic differences in looks took a few thousand years. Preference for leaves, terminal bud, lateral bud, stem, and inflorescence resulted in selection of varieties of wild cabbage into the many forms known today.

Figure 3: Plant varieties of Brassica oleracea species as a result of artificial selection

The Mendel Era

Arguably the most significant development in plant breeding is the principle of genetics. Austrian researcher, Gregor Mendel, is considered the “father of modern genetics” based on his foundational work in the late 18th century describing how factors for specific plant characteristics are transmitted from parents to offspring in subsequent generations.

Mendel’s famous experiment is his ground-breaking work surrounding the inheritance of pea plants. Mendel demonstrated when breeding a pure-bred yellow pea plant with a pure-bred green pea plant, offspring always produced yellow seeds and termed the yellow pea a “dominant” trait. Mendel then bred a second generation of pea plants from the hybrids (the yellow offspring) and found the reappearance of green seeds at a ratio of 3 yellow to 1 green. Mendel found that the green trait, for which he deemed a “recessive” trait, was hidden in the first generation from the dominant yellow trait.

From the results of his experiment, Mendel led the way to understand modern plant breeding by determining how traits are passed from generation to generation. The combination of recessive and dominant traits, known as alleles, produces genes that are passed down to their offspring. The understanding of what alleles the parents hold and what traits will be produced in their genes allow for plant breeders to predictably determine the traits of offspring.

Examples: The Mendel Pea Experiment

Gregor Mendel‘s published work in 1866, demonstrated the actions of invisible “factors”—now called genes—can predictably determine the traits of an organism.

Figure 4: Characteristics of Pea Plants

Today, plant breeders use this knowledge to produce plant varieties with beneficial traits more effectively or to remove undesired characteristics. For example, a mildew-resistant pea may be crossed with a high-yielding but susceptible pea, with the intention to introduce mildew resistance to the pea with a high yield. Progeny from the cross would then be crossed with the high-yielding parent to ensure that the progeny was most like the high-yielding parent, known as “backcrossing”. This cyclical process removes most of the genetic contribution of the mildew-resistant parent.

Modern Plant Breeding

The Mendelian laws of genetics marked the beginning of modern plant breeding, which has continuously developed since. In the late 1950s, the tremendous increase of grain yield associated with improved genetics was known as the Green Revolution. In addition to improved farming techniques and the application of plant protection chemicals and mineral fertilizers, the global grain production between 1960 and 2000 was almost double what it was for the entire 10,000 years prior. The Green Revolution raised incomes for farmers, enhanced the economy, and saw a decline in poverty.

As newer technology became available, “DNA” was discovered to be genetic material and was key to understand genetics on a molecular level. The use of biotechnology and genetic engineering facilitates plant breeding by allowing scientists to circumvent the reproduction process of plants and transfer specific DNA from one parent to another. Molecular breeding allows for greater precision when altering plant genetics to produce new and desirable varieties.

Where many different genes can influence a desirable trait in plant breeding, marker-assisted selection is used to identify the location and function (phenotype) of various genes within the genome. The mapping allows plant breeders to screen for desired traits in large populations of plants. Genetic modification of plants is then achieved by adding a specific gene or genes to a plant, or by knocking down a gene to produce a desirable phenotype. Genetic modification can produce a plant with the desired trait or traits faster than classical breeding because the majority of the plant’s genome is not altered.

Issues and Concerns

Plant breeding, whether classical or through genetic engineering, raises concerns regarding agricultural plant varieties. Some unintended effects of plant breeding include the safety and nutritiousness of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and the reduction in plant diversity.

There is a growing skepticism that biotechnology may result in toxins that can be potentially hazardous to human and animal health worldwide, particularly in Europe. Many environmental activist groups in Europe, such as Greenpeace, have been protesting GMOs for many years and voicing their concern about GMOs’ potential to cause harm to human and animal health and ecosystems that is fueled by food safety issues such as Mad Cow disease and asbestos. To these organizations, the benefit of enhanced plant varieties through modern plant breeding technologies is outweighed by the potential risks to food safety.

Another issue raised in plant breeding is its effect on nutritional value. A study published on food composition data in the Journal of the American College of Nutrition in 2004 found decreases in six of 13 nutrients measured in the plants studied. The study, conducted at the Biochemical Institute, the University of Texas at Austin, concluded in summary:

“We suggest that any real declines are generally most easily explained by changes in cultivated varieties between 1950 and 1999, in which there may be trade-offs between yield and nutrient content.”

Lastly, there exists a concern for biodiversity. Genetically engineering crops can limit biodiversity by reducing the genetic variability within a species. Biodiversity is important for the sustainability of our ecosystem, while genetic diversity is important for sustainable crop production. Another concern is related uncertainty of the long-term effects of a reduction in biodiversity. For instance, if a single gene may be the determinant to provide resistance to a life-threatening disease was lost as a result of genetic engineering. When systems selectively choose genes that are beneficial to increased crop production but loses other traits and characteristics in the process, we could lose potentially valuable traits that we don’t yet know are valuable.

Bio and genetic diversity are not only of great importance to the maintenance of our ecosystem and crops but also to the farming industry. Variability within a crop species is essential for the developing traits of disease resistance, tolerance to the environment, yield, and quality improvements, which can be crucial to the success of farmers. In addition, having the ability to select different crop species increases a farmer’s arsenal for events, such as pest infestations, climate shifts, or new market pressures.

However, many poor farmers in developing countries do not have access to the resources to capitalize on modern breeding technology. Due to the complexity and infrastructure needed to conduct genetic engineering, many plant varieties are under the control of larger corporations and can be expensive to access due to the price of seed and intellectual property rights. Farmers who do not have the resources to access the improved plant varieties exacerbate the negative effects of poverty in some countries.

Where there are several pros and cons of the advancement of genetic engineering in plant breeding, it is essential to weigh the factors before embarking on the new technology.

3. Intellectual Property Protection: Plant Breeding

Intellectual property protection is offered to plant breeders to reward their knowledge and effort in creating improved plant varieties. Without such protection, there would be little incentive for plant breeders to carry out expensive and time-consuming breeding programs. The development of biotechnology and genetic engineering requires breeders to have a vast array of expert knowledge and technological resources. Intellectual property rights stimulate investment in the research and development of new plant varieties by granting rightsholders exclusive rights and the ability to earn licencing royalties.

International Context

In the early days of plant breeding, breeders protected their newly developed varieties through mechanisms such as trade secrets and contractual agreements. Plant varieties were seen more as a product of nature than produced by human intervention. As the complexity of plant breeding grew, as did the need for a stronger reward for breeding improved varieties.

In 1938, plant breeders came together to form the International Association of Plant Breeders for the Protection of Plant Varieties (ASSINSEL) which sought to establish a system that could reward plant breeders for their efforts while encouraging them to develop improved plant varieties. The association resulted in governments gaining interest in developing intellectual property protection for breeders that met the goals of ASSINSEL. Today, intellectual property protection for new plant varieties is offered in the form of patents or a sui generis form of protection, known as Plant Breeders’ Rights (PBR).

The system of protection used in each jurisdiction will be determined by national legislators of each country. Many large countries around the world adhere to the model system of Plant Breeders’ Rights set out by the International Union for the Protection of Plant Varieties (UPOV). UPOV was formed in 1961 with the mission to “provide and promote an effective system of plant variety protection, with the aim of encouraging the development of new varieties of plants, for the benefit of society”.

The UPOV Convention was established by the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, which sets minimum standards of protection for plant varieties in the form of PBR. Given the specific nature of the legal mechanism, national legislation generally follows the UPOV Convention very closely.

The Convention was first signed in Paris in 1961 upon creation and was later revised in 1972, 1978, and 1991. While member countries have the principal discretion to decide which version of the Convention they will implement in their domestic laws, a country’s decision is often dictated by the level of protection guaranteed by its closest commercial competitors. UPOV 1991 shows a significant difference in the standard of protection offered to rightsholders than its predecessors while allowing for the possibility of dual protection with patent rights if they so choose. Today, most of the 77 Contracting Parties have opted for the most recent version of the Convention.

While the UPOV Convention clearly sets out its requirements, plant variety protection is still flexible. Nations may offer stronger protection to breeders through patent protection for eligible plant varieties. Article 27.3(b) of the TRIPS agreement addresses the patentability of plants, allowing for members to exclude plant varieties from their patent regime. However, the provision requires members of the WTO to provide some protection for plant varieties, “…either by patents or by an effective sui generis system or by any combination thereof”.

Each jurisdiction must offer some protection to plant varieties but can choose whether they use a tailored form of protection, an existing regime, or a combination of both. The breeding method may also determine the range of different intellectual property rights a breeder can receive. Nations typically seek out stronger protection in the form of patents when a more complex breeding technique is used. For example, a patent may be issued for only genetically engineered plant varieties, as it requires a greater level of human intervention in which a plant variety derived from the selection of propagated material does not.

Canadian Context

Canada is a signatory to the UPOV Convention and in 1990 the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act (PBRA) was enacted to provide a sui generis system of protection for new plant varieties, based upon the 1978 Act of the UPOV Convention (UPOV 1978). Unlike all other intellectual property regimes in Canada which fall under the purview of the Canadian Intellectual Property Office, the PBRA is administered by the Plant Breeders’ Rights Office (PBRO), which is a part of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). The PBRO works independently under the authority of the Commissioner of Plant Breeders’ Rights to grant protection to new plant varieties in Canada.

In February 2015, significant changes to the PBRA and the accompanying Plant Breeders’ Rights Regulations (PBRR) were made to bring into conformity with the Convention’s most recent text, the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention (UPOV 1991). The amendments provide stronger protection for plant breeders by expanding the scope of PBRs. The purpose of the expansion is to create an environment that encourages the development of new plant varieties, harmonizes protection with major trading partners, and gives farmers greater access to new and innovative varieties, allowing them to be more competitive in the global marketplace.

As discussed in more detail in Chapter IV of this textbook, higher life forms are not patentable in Canada. The Supreme Court decision of Harvard College v. Canada (Commissioner of Patents) (2002 SCC 76 at paragraph 189) makes clear that although the Canadian Patent Act can be used to encourage investment in the field of biotechnology, plant varieties are a subset of a higher life form, thus not patentable. The decision argues that if plant varieties were to be patentable under the Patent Act, there would be no need for Canada to pass the PBRA.

However, innovations that happen at a cellular level may be protected by patents. Monsanto Canada Inc. v. Schmeiser (2004 SCC 34 at paragraph 168), the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the validity of Monsanto’s patent of their “Roundup Ready Canola”. The court ruled that the Patent Act protects genetically modified genes and cells, giving the owner exclusive rights to the technology. The decision shows that while the Patent Act does not explicitly protect the plant variety itself, it can be indirectly protected by protecting methods required to reach the final plant variety.

Comparative Nations

The 1991 UPOV Act is the main model for the legislation among most member countries. While the PBRA is the main source of legislation in Canada, other nations with large breeding programs differ in their plant variety protection regimes, some offering stronger protection and different characterizations of plants eligible for protection.

The United States offers the strongest protection to plant breeders, providing both plant variety and patent protection. The American Plant Variety Protection Act (7 USC 2321) mirrors that of UPOV 1991, providing protection to sexually reproduced or propagated varieties. Asexually reproduced plants are then protected under the Plant Patent Act (35 USC 161), which are varieties reproduced by grafting or cuttings, mostly seen in ornamentals and fruit trees. Lastly, both sexually and asexually produced varieties may be protected by utility patents in the United States if the criteria is met, and is the most comprehensive protection of them all.

By contrast, European laws do not allow for patenting of plant varieties, but like Canada can be indirectly patented. The Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office stated in 2000 that when a plant variety is not individually claimed, it is not excluded from patentability. The Board explained that a plant patent could be issued to a gene sequence(s) that characterizes the modified plants rather than one part of its individual genotype. For example, a plant grouping that contains a special disease-resistant gene can be patented because it is characterized as the gene-resistant element, not the plant itself.

B. Requirements

Intellectual property rights granted to the subject matter in Canada work to incentivize the creation of value within society through the development of new ideas and by providing public access to certain goods or services. Intellectual property rights come in different statutory forms and the applicable subject matter and purpose will determine its requirements. The Canadian Plant Breeders’ Rights Act closely mirrors the sui generis system set out by Chapter III (Articles 5-9) of the UPOV 1991 Act and will be closely used to describe Canadian requirements.

1. Eligibility

To obtain PBRs an applicant must present a plant variety that belongs to a prescribed category and meets the definition and conditions set out in the PBRA, per S.4(1). Prescribed categories are set out in Schedule I of the Plant Breeders’ Rights Regulations (PBRR), which lists the known common and botanical names of plants. The list of prescribed categories is not fixed, as item 40 of the list states “all other categories of the plant kingdom, except algae, bacteria, and fungi”.

S.4(1) Plant breeder’s rights may not be granted except in respect of a plant variety that belongs to a prescribed category and meets all of the conditions set out in subsection (2).

S.2 plant variety means any plant grouping within a single botanical taxon of the lowest known rank that, whether or not the conditions for the grant of plant breeder’s rights are fully met, is capable of being

(a) defined by the expression of the characteristics resulting from a given genotype or combination of genotypes,

(b) distinguished from any other plant grouping by the expression of at least one of those characteristics, and

(c) considered as a unit with regard to its suitability for being reproduced unchanged; (variété végétale)

Explanatory Notes on the Definition of Variety provided by the UPOV Convention in relation to the UPOV 1991 Act clarifies a “plant grouping within a single botanical taxon” means it is one of its own kind. Although a plant variety will be encompassed within larger groups (i.e., species, plant kingdom), it is represented as a smaller group within. In this respect, a plant variety does not refer to one single plant. It will be defined by its own characteristics and/or breeding technologies that are used to produce a single plant.

A set of rules and recommendations dealing with formal botanical names given to different groups of plants and organisms can be found in the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN). The ICN is amended every six years at the International Botanical Congress and aims to provide a”stable method of naming taxonomic groups, avoiding and rejecting the use of names that may cause error or ambiguity or throw science into confusion”. Article 4 of the ICN describes a “variety” to be a secondary ranking to “species” and provides further nomenclature for the detailed classification of rankings.

International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code)

Chapter I (Article 4)

Taxa And Their Ranks

4.1. The secondary ranks of taxa in descending sequence are tribe (tribus) between family and genus, section (sectio) and series (series) between genus and species, and variety (varietas) and form (forma) below species.

4.2. If a greater number of ranks of taxa is desired, the terms for these are made by adding the prefix “sub-” to the terms denoting the principal or secondary ranks. An organism may thus be assigned to taxa at the following ranks (in descending sequence): kingdom (regnum), subkingdom (subregnum), division or phylum (divisio or phylum), subdivision or subphylum (subdivisio or subphylum), class (classis), subclass (subclassis), order (ordo), suborder (subordo), family (familia), subfamily (subfamilia), tribe (tribus), subtribe (subtribus), genus (genus), subgenus (subgenus), section (sectio), subsection (subsectio), series (series), subseries (subseries), species (species), subspecies (subspecies), variety (varietas), subvariety (subvarietas), form (forma), and subform (subforma).

Figure 5: The International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants is the set of rules and recommendations that govern the scientific naming of all organisms traditionally treated as algae, fungi, or plants.

The S.2 PBRA definition of plant variety further describes that its characteristics must be capable of being defined and distinguished from other plant groupings within a species with the ability to be reproduced unchanged. When determining if conditions that are required for PBRs to be granted are met, these elements set out by the S.2 definition are extremely important. However, the definition of plant variety may be met and still not be eligible for protection if it is not sufficiently distinct, uniform, and/or stable with regard to its said characteristics.

2. Conditions

A comparable form of intellectual property protection of a plant variety is patent protection, as breeding new varieties is similar to an invention. An invention must be new, useful, and non-obvious, and requires proper disclosure. The disclosure requirement for patents provides public access to the information in return for the exclusive rights of its owner. In contrast, disclosure of a plant variety is not of the same benefit to the public in the case of PBRs, as plants are living things that constantly change and reproduce. The development of new varieties may occur through human intervention, however, its value does not lie with the specificity of one organism at one point in time.

With the help of UPOV and other international organizations, Canadian provides a statutory regime that is specifically tailored to the nuances of plant varieties while meeting its purpose of incentivizing the creation of new plant varieties that will benefit society. Conditions set out by subs.4(2) of the PBRA require that a plant variety be new, clearly distinguishable from varieties of common knowledge, stable, and sufficiently homogenous.

S.4(2) Plant breeder’s rights may be granted in respect of a plant variety if it

(a) is a new variety;

(b) is, by reason of one or more identifiable characteristics, clearly distinguishable from all varieties whose existence is a matter of common knowledge at the filing date of the application for the grant of plant breeder’s rights respecting that plant variety;

(c) is stable in its essential characteristics in that after repeated propagation or, if the applicant has defined a particular cycle of propagation, at the end of each cycle it remains true to its description; and

(d) is, having regard to the particular features of its sexual reproduction or vegetative propagation, a sufficiently homogeneous variety.

Novelty

Subsection 4(2)(a) of the PBRA sets out that a plant variety must be new to be granted PBRs. The determination of novelty is solely based on whether a plant variety has been sold in the marketplace for a prescribed period set out by subs.4(3) of the PBRA.

S.4(3) A plant variety is a new variety if the propagating or harvested material of that variety has not been sold by, or with the concurrence of, the breeder of that variety or the breeder’s legal representative

(a) in Canada, before

(i) the prescribed period preceding the filing date of the application for the grant of plant breeder’s rights, in the case of a variety belonging to a recently prescribed category, and

(ii) the period of one year before the filing date of the application for the grant of plant breeder’s rights, in the case of any other variety; an

(b) outside Canada, before

(i) the period of six years before the filing date of the application for the grant of plant breeder’s rights, in the case of a tree or vine, and

(ii) the period of four years before the filing date of the application for the grant of plant breeder’s rights, in any other case.

A new plant variety cannot have been sold in Canada prior to the application being filed if it belongs to a prescribed category, or one year prior if it does not. Prior to the 2015 amendments to the PBRA, no disclaimer existed, and a variety could not be claimed as new if it was sold within Canada prior to its assigned application filing date.

A new plant variety may qualify as new if it has been sold outside of Canada for up to four years prior to the date rights are granted if it is a tree or vine, and up to six years if it is not. The difference in requirements assigned to new varieties inside and outside of Canada exists because it is very common for plant breeders to seek protection in multiple jurisdictions.

When considering whether a variety is “sold”, it does not necessarily mean a single plant itself. A variety is considered sold if its propagating or harvested materials have been commercialized. See the definition of “propagating material” below.

S.2 propagating material means any reproductive or vegetative material for propagation, whether by sexual or other means, of a plant variety, and includes seeds for sowing and any whole plant or part thereof that may be used for propagation; (matériel de multiplication)

Distinctness, Uniformity, and Stability

Paras. 4(1)(b)-(d) of the PBRA require a plant variety to be distinct, stable, and uniform, respectively, and are known as the DUS requirements. Determination of DUS requirements relies on the characteristics of the plant variety and will vary based on its prescribed category.

Distinctness

The requirement of distinctness in the PBRA act ensures a plant variety is measurably different from varieties whose existence is of common knowledge at the time the application was filed.

International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (1991)

Article 7

Distinctness

The variety shall be deemed to be distinct if it is clearly distinguishable from any other variety whose existence is a matter of common knowledge at the time of the filing of the application. In particular, the filing of an application for the granting of a breeder’s right or for the entering of another variety in an official register of varieties, in any country, shall be deemed to render that other variety a matter of common knowledge from the date of the application, provided that the application leads to the granting of a breeder’s right or to the entering of the said other variety in the official register of varieties, as the case may be.

Although no explicit definition is provided in the PBRA or UPOV 1991 Act, UPOV publication “Varieties of Common Knowledge” explains common knowledge to be considered a worldwide test that uses its natural meaning. In determining common knowledge, documented knowledge and relevant knowledge of communities around the world if credibly substantiated should be taken into account. Canadian legislation provides similar guidance in subs.5(1) of the PBRR, focusing on commercialization and access to the public.

S.5 For the purposes of paragraph 4(2)(a) of the Act, the following criteria shall be considered when determining that the existence of a plant variety is a matter of common knowledge, namely,

(a) whether the variety is already being cultivated or exploited for commercial purposes; or

(b) whether the variety is described in a publication that is accessible to the public.

A plant is distinct if when comparing it to all other varieties of common knowledge with similar characteristics, it is clearly distinguishable. The UPOV Convention does not set out clear guidelines as to how members of the union should determine distinctness, but states members “may develop their own systematic way . . . based on the principles laid down in [its “Examining Distinctness”] document.”

A plant variety may be deemed to be clearly distinguishable based on its written description and does not necessarily require a complete growing trial. The description must be sufficient to make the distinction. Cooperation with other union members is encouraged, as protection for the same plant variety sought in multiple jurisdictions is common.

Standardization of the level of distinctness required is found in Test Guidelines (TG) provided by the UPOV Convention. Technical questionnaires are provided for prescribed categories of plant varieties tailored to their unique characteristics. Candidate varieties will be found distinct if characteristics are clear, which can be accomplished through qualitative and quantitative characteristics, as well as statistical, measured, and visual assessments.

Uniformity

The requirement of uniformity ensures a plant variety does not vary in terms of its characteristics. Article 8 of the UPOV 1991 Act explicitly uses the term “sufficiently uniform” to describe the requirement.

International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (1991)

Article 8

Uniformity

The variety shall be deemed to be uniform if, subject to the variation that may be expected from the particular features of its propagation, it is sufficiently uniform in its relevant characteristics.

The equivalent provision in the PBRA is found in para.4(2)(d) which uses the term “sufficiently homogenous”. Any variation should be predictable to the extent it can be described by the breeder and should be commercially acceptable.

The UPOV Convention makes clear in its “Examining Uniformity” document that a plant variety cannot vary, so far as it is necessary, in order to be granted protection. A plant is unique to subject matter offered copyright, trademark, or patent protection because it is a living organism subject to some natural variation and is incapable of being precisely defined. Thus, the criterion for uniformity is not absolute and will take into account the nature of the variety. For example, the level of uniformity will differ based on self-pollinated/vegetative propagated varieties, cross-pollinated varieties, and hybrid varieties. Furthermore, it relates only to the characteristics which are relevant for the protection of the variety.

Stability

The stability requirement ensures that a plant variety does not change over time. Para.4(2)(c) of the PBRA sets out that a plant variety must not alter its essential characteristics over successive generations to be deemed stable. In addition, the plant variety must be stable to the degree that further generations of seed or propagating material exhibit the same essential characteristics. Such requirement is closely mirrored in Article 9 of the UPOV 1991 Act.

International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (1991)

Article 9

Stability

The variety shall be deemed to be stable if its relevant characteristics remain unchanged after repeated propagation or, in the case of a particular cycle of propagation, at the end of each such cycle.

Testing for stability is not as certain as testing for other DUS requirements because its examination refers to the stability of the variety itself and not its propagating material. To be sure the condition is met, it may be necessary that the candidate variety is tested through growing a further generation or continued testing. However, testing for stability is closely related to testing for uniformity. In many types of variety, if it has shown to be uniform, the material produced will likely confirm the characteristics of the variety over time and meet the stability requirement.

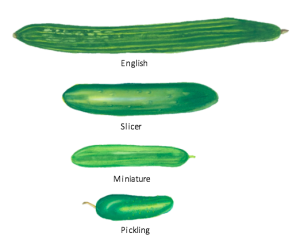

EXAMPLE: Cucumis Sativus

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) is a widely-cultivated creeping vine plant that bears cylindrical fruits, which are used as vegetables. Some of the most popular varieties of the cucumis sativus species include the English, Slicer, Miniature, and Pickling Cucumber.

Figure 6: Main varieties of cucumbers

Each variety of cucumber holds its own characteristics. English cucumbers are long, slender, and seedless, whereas slicer cucumbers are generally long and dark green with smooth, thick skin. An applicant seeking PBR protection and conducting DUS testing on a new cucumber variety would be required to show that the new variety’s characteristics were distinct from similar cucumber varieties, including those of English and Slicer cucumbers.

To meet the uniformity requirement, the applicant would then need to show that the characteristic which made the cucumber variety distinct existed in each of the cucumbers grown. To meet the stability requirement, those characteristics could not change over time. For example, an English cucumber could meet the DUS requirements if its long, slender characteristics were distinct from other varieties, was the same in each fruit, and did not lose its distinct shape over time.

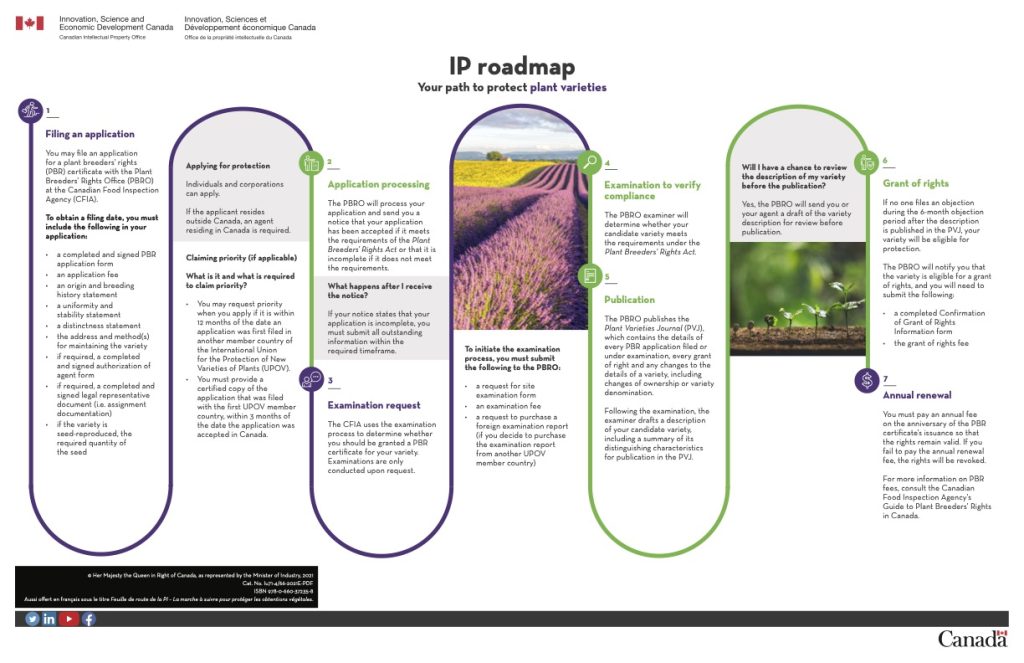

C. Application Process

The UPOV Convention requires each of its members to establish a PBRO that is in charge of applications for PBR. A PBRO will develop application forms, publish information, and ultimately decide whether a PBR will be granted. The application process will differ based on the formalities set out by each union member and will be necessary to complete for any applicant to be granted PBRs in that jurisdiction. However, UPOV sets out clearly in the “Guidance for Members of UPOV” publication what the steps are for the administration of PBRs.

In Canada, a PBR application will be filed with the PBRO at the CIFA. Upon the completion of an application form and acceptance from the office, an examination of the application will determine whether the variety meets the DUS requirements. If no objections are received, the PBRO will determine whether the applicant will be granted a PBR certificate.

Figure 3: IP Roadmap

1. Filing the Application

A person interested in filing an application with the PBRO must meet all requirements set out in subs.19(1) of the PBRR by completing the “PBR Application for Filing Purposes” form. For foreign applicants, an authorized agent who is a Canadian resident must be appointed to be a main contact for the PBRO.

S.19(1) An application for the grant of plant breeder’s rights shall be made to the Commissioner and contain the following information:

(a) the name and address of the applicant;

(b) the name and address of the breeder, if different from the applicant;

(c) the name and address of any agent or legal representative, where applicable;

(d) the botanical and common names of the plant variety;

(e) the proposed denomination;

(f) whether an application for a protective direction is included;

(g) a description of the plant variety;

(h) a statement that the plant variety is a sufficiently homogeneous variety within the meaning of subsection 4(3) of the Act and is stable;

(i) the manner in which the plant variety was originated;

(j) where an application for plant breeders’ rights respecting the plant variety has been made or granted in any country other than Canada, the name of the country;

(k) whether priority is being claimed as a result of a preceding application made by the applicant in a country of the Union or an agreement country;

(l) where the breeder or a legal representative of the breeder sold or concurred in the sale of the plant variety within or outside Canada, the date of the sale;

(m) where applicable, any request for exemption from compulsory licencing; and

(n) the manner in which the propagating material will be maintained.

Variety Denomination

Para. 19(1)(e) of the Regulations requires an application to provide a proposed denomination at the time of filing for the candidate plant variety. Section 14 of the PBRA sets out the principles and acceptability of a proposed variety denomination.

S.14(1) A plant variety in respect of which an application for the grant of plant breeder’s rights is made shall be designated by means of a denomination proposed by the applicant and approved by the Commissioner.

S.14(2) Where a denomination is proposed pursuant to subsection (1), the Commissioner may, during the pendency of the application referred to in that subsection, reject the proposed denomination, if considered unsuitable for any reasonable cause by the Commissioner, and direct the applicant to submit a suitable denomination instead.

S.14(3) A denomination, in order to be suitable pursuant to this section, must conform to the prescribed requirements and must not be such as to be likely to mislead or to cause confusion concerning the characteristics, value or identity of the variety in question or the identity of its breeder.

S.14(4) A denomination that the Commissioner approves for any plant variety in respect of which protection has been granted by, or an application for protection has been submitted to, the appropriate authority in a country of the Union or an agreement country must, subject to subsections (2), (3) and (5), be the same as the denomination with reference to which that protection has been granted or that application submitted.

S.14(3) A denomination approved by the Commissioner pursuant to this section may be changed with the Commissioner’s approval in the prescribed circumstances and manner.

S.14(4) Where a trademark, trade name or other similar indication is used in association with a denomination approved by the Commissioner pursuant to this section, the denomination must be easily recognizable.

In the case of a plant variety that is protected or is in the process of an application for protection in another jurisdiction, a “one variety, one name” policy is implemented, reflecting the importance of using a single denomination for each variety worldwide. If a denomination accepted in another country is found to be unacceptable in Canada, the foreign denomination will be listed as a synonym to the accepted Canadian denomination.

A variety denomination cannot be trademarked in Canada because the owner of PBRs is required to provide free use of the variety denomination after the rights expire. Where a trademark can last indefinitely, the denomination would not be free of use. However, marking names (that may be trademarked) can be used in association with the variety denomination if the denomination is “easily recognizable”.

Among the limited case law surrounding Plant Breeders’ Rights, a 2001 Federal Court case University of Saskatchewan v. Canada (Commissioner of the Plant Breeders’ Rights Office) (2001 FCT 134) demonstrated that an error in denomination may be corrected by the PBR holder pursuant to s.23 of the PBRR, with limited restriction from the Commissioner.

Provisional Protection

S.19(1) Subject to subsection (2), an applicant for the grant of plant breeder’s rights in respect of a plant variety has, as of the filing date of the application, the same rights in respect of the variety that he or she would have under sections 5 to 5.2 if plant breeder’s rights were to be granted.

Provisional protection, known previously as protective direction, is offered to a candidate plant variety from the day the PBR application is first filed until the date when rights are granted. Applicants may take legal action after rights are granted for any infringements that may have occurred while the application was in progress.

Amendments to the PBRA in 2015 altered the availability of protection during the application process. If an application was filed before February 27, 2015, protective direction could be withdrawn if propagating material sold by the applicant. If an application was filed on, or after, February 27, 2015, there are no restrictions on the sale of variety. However, pursuant to subs.19(2) of the PBRA, an applicant’s right to remuneration exists only if the other party was aware an application had been filed.

Claiming Priority

An application originally filed in Canada may serve as a basis for claiming priority for a PBR application filed in another UPOV, WTO, or agreement country. By claiming priority, the applicant would have precedence over competitors who are applying for rights for a plant variety with identical characteristics. This means that if applications are received for two varieties that cannot be distinguishable from one another after the examination process, the variety with the PBR application that was filed first is granted the rights. The variety that was filed later would not be eligible for protection, as it would not meet the distinctness requirement. The date when the preceding application was filed would be considered as the filing date of the PBR application in Canada.

S.11(1) If an application made under section 7 is preceded by another application made in a country of the Union or an agreement country for protection in respect of the same plant variety and the same breeder, the filing date of the application made under section 7 is deemed to be the date on which the preceding application was made in that country of the Union or agreement country and, consequently, the applicant is entitled to priority in Canada despite any intervening use, publication or application respecting the variety if

(a) the application is made in the prescribed form within 12 months after the date on which the preceding application was made in that country of the Union or agreement country; and

(b) the application is accompanied by a claim respecting the priority and by the prescribed fee.

A claim for priority must be requested by the applicant within 12 months from the date when the first PBR application was filed in a UPOV member country, agreement country or WTO member country. A copy of the preceding application, certified by an authority from the UPOV member country, agreement country or WTO member country must be submitted within the 3 months following the request for claiming priority. A request for claiming priority must be made at the time of filing a PBR application and include the prescribed fee.

2. Examination Process

Article 12 of the 1991 UPOV Act requires that a plant variety be examined in order to determine it meets the DUS requirements of protection. The examination or the “DUS Test” consists of a series of comparative growing tests which generate a description of the variety. The relevant characteristics of a variety will be described to determine whether the candidate variety meets the DUS requirements.

In Canada, PBRO conducts the DUS test but incorporates a breeder-run testing system, where initial trials are conducted by the applicant. After a Request for Site Examination has been submitted, the applicant can conduct independent comparative tests and trials for the PBRO to review and determine whether an independent trial examination is necessary to verify results.

Successful completion of the examination process requires the applicant for PBRs to submit a completed Test Guideline that is relevant to the plant variety, a description of the comparative tests and trials, and photographs that clearly distinguish the candidate from reference varieties. The three submissions must be submitted to the PBRO within six months of the date on which the examination was conducted.

Test Guidelines

In its document General Introduction to the Examination of Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability and Development of Harmonized Descriptions of New Varieties of Plants (TG/1/3), the UPOV Convention sets out principles to be adhered to during DUS examinations. The UPOV principles ensure that testing is being conducted in a harmonized way among all member countries.

The document outlines the usage of “Test Guidelines” (TG) created for individual species or variety groupings. The TGs provide examiners recommendations for the method of DUS examination, a table of relevant characteristics to consider, and particular guidelines relevant to the variety. TGs are not exhaustive, the PBRO has the authority to introduce additional testing criteria as they see fit. However, in practice, TGs used by the PBRO are almost identical to those provided by the UPOV Convention.

The individual TGs are prepared by a UPOV Technical Working Party that is composed of experts appointed by the government of each member of the Union. Internationational non-governmental organizations who are in the field and/or industry of plant breeding are also given the opportunity to comment on the proposed TGs. Once all parties are in agreement, TGs are submitted for final approval by a UPOV Technical Committee.

All TGs are available to the public on the UPOV Test Guidelines Database. In the event that TGs have not been previously established by the Convention or other union members, the DUS examiner is to proceed with similar procedures used to develop the TGs (9.3 TG/1/3).

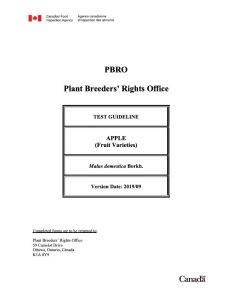

EXAMPLE: Apple Test Guideline

The Test Guideline for Apple (fruit varieties) of the Malus Domestica Borkh species provided by the PBRO outlines the relevant characteristics for the specific plant type. The TG outlines the specific protocols for its examination and groups characteristics into appropriate categories. For Apple varieties, data must be collected for the duration of 1 growing cycle and the plants are to be assessed when at an appropriate maturity level.

The description form for the applicant can be found in Section F of the TG. The table of characteristics highlights those with an asterisk to communicate which characteristics are required for the TG to be accepted.

Figure 5: APPLE (Fruit Variation), Malus domestica

Examining Distinctness

A variety eligible for PBR protection must be clearly distinguishable from any other variety whose existence is a matter of common knowledge. In testing for distinctness, all varieties of common knowledge will be considered, however, a systematic individual comparison will not be required for varieties for which the candidate variety is sufficiently different.

Supplementary procedures such as publications of variety descriptions, comments from interested parties, or cooperation between members of the Union to exchange technical information can be used when determining if the candidate variety is distinct from other varieties of common knowledge.

Within the TGs exists a “Techincal Questionnaire” which must be submitted with the examination. The questionnaire seeks information on certain characteristics important for distinguishing varieties. Some characteristics will be compulsory and others recommended, and fall within a 1-9 scale. Characteristics used to describe both the candidate variety must also be described for all reference varieties (2.3 TGP/9/1).

Characteristics must be both consistent and clear to be distinguishable (5.3.3 TG/1/3). Consistency may be found when the difference in characteristics is found on at least two independent occasions, taking into account circumstances such as environmental influence. Determining whether a difference in characteristic is clear will be dependent on many factors and should consider the expression of such characteristics (i.e., from qualitative, quantitative, and pseudo-qualitative sources). Section 4 of UPOV publication “Examining Distinctness” provides detailed guidance for the observation of each of the listed characteristics.

Examining Uniformity

A protected variety meets the uniformity requirement if it is sufficiently uniform in its relevant characteristics. All obvious characteristics are relevant, whether set out within the TGs or not. The uniformity requirement is linked to the particular features of the candidate variety’s propagation and the level of uniformity among different variety groups will differ based on the nature of its species.

Testing for uniformity is completed by examining the variation between propagated material through visual assessment and measured characteristics (i.e., length and width). It is possible that a plant variety is a uniform while still producing different plants or “off-types”. In this case, uniformity will be assessed by considering all propagating materials and the overall range of variation, rather than the comparison of propagating material to a single plant (4 TGP/10/2).

Examining Stability

A protected variety meets the stability requirement if its relevant characteristics remain unchanged after repeated propagation. Similar to the examination of uniformity, all obvious characteristics are relevant, including those listed in its appropriate TGs.

In practice, no particular tests are necessary for the examination of stability. If the candidate variety meets the requirement for uniformity, it can also be considered stable. However, if a breeder cannot provide material conforming to the characteristics of the variety at any time, the PBRs may be repealed or not granted (2.3 TGP/11/1).

3. Granting Rights

If after the examination process has been completed, the PBRO deems all requirements have been met, and there are no valid objections, the applicant will be notified that they are eligible for grant of PBR rights and can continue with the necessary forms and fees to finalize ownership.

In the case of a variety for which PBRs have been granted prior to the amendments to the PBRA in 2015, protection is granted for a period of up to 18 years. In the case of PBRs granted after the 2015 amendments, PBRs are granted for a period of up to 25 years for the variety of a tree and vine, and 20 years for all other varieties. In both cases, rights are effective from the date of issuance of rights. Annual renewal fees must be paid to maintain such rights.

The Commissioner may refuse or reject an application, pursuant to S.17(1) PBRA, if the candidate is not a new variety, the applicant is not entitled to apply for rights, or if any of the requirements set out by the PBRA or PBRR have not been met. However, before rejecting the application, the Commissioner must inform the applicant of the reasons for the intended rejection or refusal so the person has a chance to make representation in support of his/her application.

S.27(2) If the Commissioner is not satisfied as described in subsection (1), the Commissioner shall refuse the application.

(…)

S.27(4) The Commissioner shall not refuse the application of a person for the grant of plant breeder’s rights without first giving the person notice of the objections to it and of the grounds for those objections as well as a reasonable opportunity to make representations with respect thereto.

If PBR rights have been granted by the Commissioner, maintenance requirements set out by S.34 and S.35 of the PBRA must be met or rights may be revoked. Similar to a refusal of an application, the Commissioner will inform the rightsholder of the reasons for potential revocation or annulment and will have the opportunity to make representations in support of their PBRs. If the Commissioner requesting information and there no activity within 6 months, an application may be deemed abandoned.

An applicant may withdraw a PBR application at any time prior to the grant of rights. All documents and materials submitted in connection with the application will be returned to the applicant.

Objections

All information concerning PBR application statuses, rights granted, and any changes to the details of varieties is published by the PBRO in the Canadian Plant Varieties Journal (PVJ). The PVJ contains provides an opportunity for interested persons to review information concerning a variety and potentially file an objection to the application or any details thereof.

S.22(1) A person who considers that an application in respect of which particulars have been published under section 70 ought to be refused on any ground that constitutes a basis for rejection under section 17 or that a request in the application for an exemption from compulsory licensing ought to be refused, may, on payment of the prescribed fee, file with the Commissioner, within the prescribed period beginning on the date of publication, an objection specifying that person’s reasons. The prescribed fees are not required in the case of an objection made for the purpose of this subsection under the authority of the Minister of Industry after notice under subsection 70(2).

(…)

S.22(3) Where it appears to the Commissioner that there is good reason for rejecting an objection referred to in subsection (2), the Commissioner shall give the person making the objection a reasonable opportunity to show cause why the objection should not be rejected and, if the person shows the Commissioner no such cause, the Commissioner shall reject the objection and give notice accordingly to the person.

An individual who wishes to file an objection must pay a prescribed fee and can file at any time throughout the application process. Subsection 22(1) requires a copy of the objection to be sent to the applicant by the Commissioner unless it is rejected per subsection 22(3).

Once the variety description and comparative trials have been published, an objection must be filed within six months of the publication date. Once the six-month period has ended, there can be no valid objections, and the variety may be granted rights given all requirements have been met.

D. Exclusive Rights

The general nature of plant breeders’ rights can be found in subsection 5(1) of the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act. The provision sets out the range of acts that a holder of PBR is exclusively entitled to perform. The acts apply specifically to propagating material of a plant variety.

S.5 (1) Subject to the other provisions of this Act and the regulations, the holder of the plant breeder’s rights respecting a plant variety has the exclusive right

(a) to produce and reproduce propagating material of the variety;

(b) to condition propagating material of the variety for the purposes of propagating the variety;

(c) to sell propagating material of the variety;

(d) to export or import propagating material of the variety;

(e) to make repeated use of propagating material of the variety to produce commercially another plant variety if the repetition is necessary for that purpose;

(f) in the case of a variety to which ornamental plants belong, if those plants are normally marketed for purposes other than propagation, to use any such plants or parts of those plants as propagating material for the production of ornamental plants or cut flowers;

(g) to stock propagating material of the variety for the purpose of doing any act described in any of paragraphs (a) to (f); and

(h) to authorize, conditionally or unconditionally, the doing of any act described in any of paragraphs (a) to (g).

The 1978 UPOV Act gave owners the exclusive rights only to sell, produce, or make repeated use of propagating material of a plant variety, in addition to allowing others to perform such acts. The amendments in 2015 to the Plant Breeders Rights Act provided protection of rights of those mentioned, as well as the conditioning, export, import, and stocking of propagating material.

It is important to note within the definition of “sell” when considering the scope of protection as it includes clear guidance as to what is allowed under the exclusive right. The right to sell includes the right to “advertise”, which is precisely defined in the PBRA and leaves little room for interpretation.

S.2 sell includes agree to sell, or offer, advertise, keep, expose, transmit, send, convey or deliver for sale, or agree to exchange or to dispose of to any person in any manner for a consideration. (vente)

S.2 advertise, in relation to a plant variety, means to distribute to members of the public or to bring to their notice, in any manner whatever, any written, illustrated, visual or other descriptive material, oral statement, communication, representation or reference with the intention of promoting the sale of any propagating material of the plant variety, encouraging the use thereof or drawing attention to the nature, properties, advantages or uses thereof or to the manner in which or the conditions on which it may be purchased or otherwise acquired; (publicité)

In addition to extending the range of acts an owner is entitled to perform, amendments in 2015 prolong the duration of the owner’s monopoly. While the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act previously granted rights for 18 years beginning the day PBR were issued, subsection 6(1) sets the term to be 25 years in the case of a tree, vine, or any category specified in the Plant Breeders’ Rights Regulations, and 20 years in any other case.

1. Harvested Material

Section 5.1 of the Plant Breeders Rights Act expands the breadth of the owner’s monopoly as protection set out in 5(1)(a) to (h) applying to propagating material, by applying it to harvested material as well.

S.5.1 Subject to the other provisions of this Act and the regulations, the holder of the plant breeder’s rights respecting a plant variety has the exclusive right to do any act described in any of paragraphs 5(1)(a) to (h) in respect of any harvested material, including whole plants or parts of plants, that is obtained through the unauthorized use of propagating material of the plant variety, unless the holder had reasonable opportunity to exercise his or her rights under section 5 in relation to that propagating material and failed to do so before claiming rights under this section.

Prior to the amendments of the PBR act in 2015, there was no mention of harvested material. Once the buyer planted the propagating material, he or she was free to collect the subsequent material and with it what they wish, without violating the PBR of the owner.

The Canadian Plant Breeders’ Rights Act nor the UPOV Convention provide no definition of harvested material. In the UPOV publication “Explanatory Notes on Acts in Respect of Harvested Material“, harvested material includes entire plants and parts of plants, which is material that can potentially be used for propagating purposes. Section 5.1 provides that the exclusive rights to any acts in respect of propagating material only apply to harvested material obtained through “unauthorized use of propagating material” and in the absence of “reasonable opportunity to exercise his or her rights”.

The unauthorized use of propagating material refers to the material used in a territory where authorization is required but was not obtained. Unauthorized acts can occur in the country in which rights were granted, as well as in other member countries of the union if there is further propagation of the variety or export of the material enabling propagation into a country that offers no protection. Unauthorized acts will occur in relation to the exclusive rights holders are granted in paragraphs 5(1)(a) and 5(1)(b) of the PBRA to produce or reproduce propagating material and stocking propagating material for purposes mentioned in (a) to (f), respectively.

A rightsholder to exercise rights requires that the breeder should first exercise rights on the propagating material, if given a reasonable opportunity to do so, before exercising rights on the harvested material. Article 14(2) of the document provides that in any action for infringement, the defendant would have to prove that the plaintiff (the holder of the right) could reasonably have exercised the right at an earlier stage. However, UPOV clarifies in the same document that the term “his [or her] right” relates to the rights in the country in which rights were granted or “in the territory concerned”. The issue arises here whether the provision creates an obligation for the breeder to protect his variety in all countries where there is a PBR system in place to “exercise” rights.

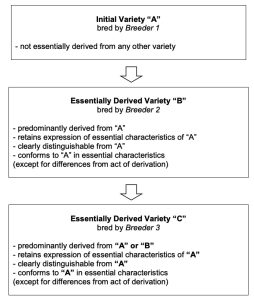

2. Essentially Derived Varieties

Section 5.2(1)(a) of the PBRA expands the scope of the owner’s monopoly to include control over plant varieties that are “essentially derived from the owner’s initial plant variety. Similar to harvested materials, before amendments to the Act there was no mention at all of “essentially derived” varieties. The amended act provides that an “essentially derived” variety must be a plant variety that is derived predominately from the initial variety and retain its same essential characteristics, is clearly distinguishable from the initial variety, and express those same essential characteristics from the initial variety.

S.5.2(1) Subject to the other provisions of this Act and the regulations, the holder of the plant breeder’s rights respecting a plant variety has the exclusive right to do any act described in any of paragraphs 5(1)(a) to (h) in respect of

(a) any other plant variety that is essentially derived from the plant variety if the plant variety is not itself essentially derived from another plant variety;

S.5.2(2) For the purpose of paragraph (1)(a), a plant variety is essentially derived from another plant variety (in this subsection referred to as the “initial variety”) if

(a) it is predominantly derived from the initial variety or from a plant variety that is itself predominantly derived from the initial variety and it retains the essential characteristics that result from the genotype or combination of genotypes of the initial variety;

(b) it is clearly distinguishable from the initial variety; and

(c) it conforms to the initial variety in the expression of the essential characteristics that result from the genotype or combination of genotypes of the initial variety, except for the differences that result from its derivation from the initial variety.

The UPOV publication “Explanatory Notes on Essentially Derived Varieties” describes the requirement of predominant derivation, as seen in paragraph 5.2(2)(a) of the Act, to be a variety that is “predominately derived from the initial variety or from a variety itself that has been predominately derived from the initial variety”. The intention that is a variety is only essentially derived when it retains virtually the whole genotype, or else it would not express the essential characteristics of the initial variety. Paragraph 6 of the document provides guidance as to what may be regarded as essential characteristics.

Explanatory Notes on Essentially Derived Varieties Under the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention

Section I

Predominantly derived from the initial variety (Article 14(5)(b)(i))

6. The following might be considered in relation to the notion of “essential characteristics”:

(i) essential characteristics, in relation to a plant variety, means heritable traits that are determined by the expression of one or more genes, or other heritable determinants, that contribute to the principal features, performance or value of the variety;

(ii) characteristics that are important from the perspective of the producer, seller, supplier, buyer, recipient, or user;

(iii) characteristics that are essential for the variety as a whole, including, for example, morphological, physiological, agronomic, industrial and biochemical characteristics;

(iv) essential characteristics may or may not be phenotypic characteristics used for the examination of distinctness, uniformity and stability (DUS);

In order for a variety to be essentially derived, it must be one that is clearly distinguishable, per paragraph 5.2(2)(b). Distinctness may be determined at the examination stage, for instance, if a breeder was seeking protection, during DUS testing. However, the two concepts are different in the sense of responsibility. The assessment in DUS testing is taking place by the PBRO office determining the grant of rights, whereas an assessment of essential derivation is based on the assessment by the PBR holder determining infringement of their rights.

Lastly, the requirement for an essentially derived variety to conform to the initial variety, per paragraph 5.2(2)(b), as described by UPOV, “must retain almost the totality of the genotype of the initial variety and be different from that variety by a very limited number of characteristics.

The expansion of rights granted to the holder is a drama with the protection of essentially derived varieties. The Plant Breeders’ Rights Act in contrast with other Canadian Intellectual Property legislation, such as the Patent Act, maintains a low threshold for the granting of rights. Where it is easy for a breeder to meet the requirements for obtaining PBRs, the right of protection of essentially derived varieties prevents breeders from seeking rights for only the slight modifications. In addition, the protection decreases plagiarism in plant breeding because all plagiaristic varieties would fall under the principle.

Figure 6: Essentially Derived Varieties (A-C)

3. National Treatment Provision

The national treatment provision provides that when a UPOV union member offers PBR protection that exceeds the minimum requirements set out by the Act, the same protections must be offered to any other union member while operating within the same jurisdiction. The provision allows Canadian residents to enjoy an increased scope of protection offered by other Union members irrespective of whether Canada offers those same protections. This provision is particularly relevant for Canadians when seeking protection in the United States, a major trading partner, as the protection offered in the US Plant Variety Protection Act encompasses a wider range of exclusive rights.

1991 Act of the UPOV Convention

Article 4

National Treatment

(1) [Treatment] Without prejudice to the rights specified in this Convention, nationals of a Contracting Party as well as natural persons resident and legal entities having their registered offices within the territory of a Contracting Party shall, insofar as the grant and protection of breeders’ rights are concerned, enjoy within the territory of each other Contracting Party the same treatment as is accorded or may hereafter be accorded by the laws of each such other Contracting Party to its own nationals, provided that the said nationals, natural persons or legal entities comply with the conditions and formalities imposed on the nationals of the said other Contracting Party.

(2) [“Nationals”] For the purposes of the preceding paragraph, “nationals” means, where the Contracting Party is a State, the nationals of that State and, where the Contracting Party is an intergovernmental organization, the nationals of the States which are members of that organization.

E. Exceptions

While the amendments of the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act effectively strengthened the rights of the holder, the Act does provide circumstances where the rights do not apply. Subsection 5.3(1) entitles users to make use of propagating material if they do so for private and non-commercial, experimental, or breeding purposes. In addition, subsection 5.2(2) entitles farmers to save propagating material and re-plant it for future harvests.

S. 5.3 (1) The rights referred to in sections 5 to 5.2 do not apply to any act done

(a) privately and for non-commercial purposes;

(b) for experimental purposes; or

(c) for the purpose of breeding other plant varieties.

Private/Non-Commercial or Experimental Purposes

Paragraph 5.3(1)(b) indicates the breeders’ rights does not extend to the use of a protected variety for experimental purposes. Thus, protected varieties may be used in research.

Paragraph 5.3(1)(a) indicates that the acts which are both of private nature and for non-commercial purposes are covered by the exception. Thus, non-private acts, even where they are for non-commercial purposes, are outside of the scope of the exemption Equally, a private act undertaken for commercial purposes.

UPOV document EXN/EXC/1 notes an act falling within the scope of the exception may be that of ‘subsistence farming’, where propagation of a variety by a farmer exclusively to produce a food crop to be exclusively consumed by that farmer and his or her dependents may be considered to fall within the meaning of the acts done privately and for non-commercial purposes.

Most infringements that would be of interest of the owner of PBRs would be those having large effect or are committed by larger entities. Many acts are of often of little consequence and are not injurious to the owner. For example, PBR holders may set aside some acts if it did not lead to commercial exploitation (in the case of experimental purposes) or if the impact is limited (in the case of private and non-commercial purposes).

The Breeders Exemption

Paragraph 5.3(1)(c) states that the rights of the PBR holder will not apply to acts done “for the purpose of breeding other plant varieties”. This fundamental exception to the scope of protection of PBR owners is known as the “breeders’ exemption” and is a cornerstone of the PBR system.

During the conference that led to the first UPOV Convention of 1961, the founding members agreed unanimously on the “principle of independence” as a basis for the PBR system, meaning that a plant variety bred by a protected plant variety is considered independent of the latter. The breeder’s exemption makes a fundamental distinction from the patent law system, as a patent dependent on an earlier patent is not one that is novel, thus not eligible for patent protection. For the founders of the UPOV Convention, the ability to breed new plant varieties from protected varieties is very important for the stimulation of innovation and creating improved plant varieties for the benefit of society and is logical when considering what plant breeding actually is.

Article 15(1)(iii) aligns with the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act but continues to state “and, except where the provisions of Article 14(5) apply”. This part of the provision emphasizes that breeding essentially derived varieties is not protected under the breeder’s exemption.

Explanatory Notes on Exceptions to the Breeder’s Rights Under the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention

Section I

Compulsory Exceptions to the Breeder’s Rights

(d) Article 15(1)(iii): the “breeder’s exemption”

(…)

11. The following scheme illustrates a hypothetical situation where a breeder uses a protected variety A and a non-protected variety B for the breeding of a new variety C. The scheme demonstrates that no authorization is required to breed variety C. Furthermore, the commercialization of variety C would not require the authorization of the breeder of variety A except where variety C was an essentially derived variety, or was a variety that required the repeated use of the protected variety A or was a variety which was not clearly distinguishable from the protected variety A (see Article 14 (5) of the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention).

Figure 5: UPOV EXN/EXC/1

Farmer’s Privilege

The most controversial exception in the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act is that of “farmers’ privilege”. Farmers’ privilege provides farmers the right to save seed from propagating material of a protected plant variety and repeat that process without infringing on the exclusive rights of the owner. Prior to the amendments in 2015, Canada aligned with the 1978 UPOV Act and had no explicit mention of the farmers’ privilege. Plant breeders had the option to charge royalties to farmers but still left open the opportunity to farmers to continue the practice of saving and re-using seeds in the absence of an agreement stating otherwise.

When the UPOV Convention created the 1991 UPOV Act, a new provision made explicit mention to the subject of farmers saving seed. Article 15(2) provides guidance on an optional farmers exemption, permitting farmers “within reasonable limits and subject to the safeguarding of the legitimate interests of the breeder” to be immune to infringement of exclusive rights of a PBR owner.