3.2 Methods of Presentation Delivery

Jordan Smith; Melissa Ashman; eCampusOntario; Brian Dunphy; Andrew Stracuzzi; and Linda Macdonald

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to

- Identify and describe the four methods of delivery

- Organize an impromptu speech

- Design a manuscript for presentation

- Explain the need for practice in delivering extemporaneously

- Explain the advantages and disadvantages of memorization

The Importance of Delivery

Delivery is what you are probably most concerned about when it comes to giving presentations. This chapter is designed to help you give the best delivery possible and eliminate some of the nervousness you might be feeling. To do that, you should first dismiss the myth that public speaking is just reading and talking at the same time. Speaking in public has more formality than talking. During a speech, you should present yourself professionally. Your clothes should be appropriate for the situation, your language should be correct and appropriate for the audience, and you should appear knowledgeable about your topic. The level of formality is determined by the context, audience expectations, and purpose of the message.

Methods of Presentation Delivery

There are four methods of delivery that can help you balance between too much and too little formality when giving a presentation.

Impromptu Speaking

Impromptu speaking is the presentation of a short message without advance preparation. You have probably done impromptu speaking many times in informal, conversational settings. Self-introductions in group settings are examples of impromptu speaking: “Hi, my name is Maru, and I’m an account manager.” Another example of impromptu presenting occurs when you answer a question such as, “What did you think of the report?” Your response has not been pre-planned, and you are constructing your arguments and points as you speak.

The advantage of this kind of speaking is that it’s spontaneous and responsive in an animated group context. The disadvantage is that the speaker is given little or no time to contemplate the central theme of their message. As a result, the message may be disorganized and difficult for listeners to follow.

This step-by-step guide that may be useful if you are called upon to give an impromptu presentation in a public setting:

- Take a moment to collect your thoughts and plan the main point you want to make.

- Thank the person for inviting you to speak. Avoid making comments about being unprepared, called upon at the last moment, on the spot, or feeling uneasy.

- Deliver your message, making your main point as concisely as you can while still covering it adequately and at a pace your listeners can follow.

- If possible, create a structure for your points. For example, use numbers: “Two main reasons . . .” or “Three parts of our plan. . .” or “Two side effects of this drug. . .” Timeline structures are also effective, such as “past, present, and future”.

- Thank the person again for the opportunity to speak.

- Stop talking (it is easy to “ramble on” when you don’t have something prepared). If in front of an audience, don’t keep talking as you move back to your seat.

Impromptu presentations are generally most successful when they are brief and focus on a single point.

For additional advice on impromptu speaking, watch the following 4 minute video from Toastmasters: Impromptu Speaking:

(Direct link to Toastmasters Impromptu Speaking)

Manuscript Presentations

Manuscript presentations are the word-for-word iteration of a written message. The advantage of reading from a manuscript is the exact repetition of original words. In some circumstances, this exact wording can be extremely important. For example, reading a statement about your organization’s legal responsibilities to customers may require that the original words be exact. Acceptable uses of a manuscript include

- Highly formal occasions (e.g. a commencement speech)

- Particularly emotional speeches (e.g. a wedding speech, a eulogy)

- Situations in which word-for-word reading is required (e.g. a speech written by someone else; a corporate statement; a political speech)

- Within a larger speech, the reading of a passage from another work (e.g. a poem; a book excerpt).

Manuscript presentations, however, have a significant disadvantage: Your connection with the audience may be affected. Eye contact, so important for establishing credibility and relationship in Western cultures, may be limited by reading; your use of gestures will be limited if you are holding a manuscript, and a handheld manuscript itself might appear as a barrier between you and the audience. The speaker can appear to be more connected to the manuscript than to the audience. In addition, it is difficult to change your language or content in response to unpredictable audience reactions.

- Write the speech in a conversational style, and

- Practice your speech so that it flows naturally.

Preparation will make the presentation more engaging and enhance your credibility:

- Select and edit material so that it fits within your time limit,

- Select material that will be meaningful for your particular audience,

- Know the material well so that you can look up at your audience and back at the manuscript without losing your place, and

- Identify key words for emphasis.

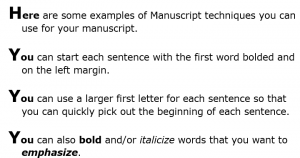

An essential part of preparation is preparing your manuscript. The following suggestions are adapted from the University of Hawai’i Maui Community College Speech Department:

Make the manuscript readable

- Use a full 8.5 x 11inch sheet of paper, not note cards.

- Print on only one side of each page.

- Include page numbers.

- Use double or triple line spacing.

- Use a minimum of 16 pt. font size.

- Avoid overly long or complex sentences.

- Use bold or highlight the first word of each sentence, as illustrated by the University of Hawai’i.

Mark up your manuscript

- Add notations—“slow down,” “pause,” “look up,” underline key words, etc. as reminders about delivery.

- Highlight words that should be emphasized.

- Add notes about pronunciation.

- Include notations about time, indicating where you should be at each minute marker.

Engage Your Audience

- Practice your presentation.

- Try to avoid reading in a monotone. Just as contrast is important for document design, contrast is important in speaking. Vary your volume, pace, tone, and gestures.

- Make sure that you can be clearly understood. Speak loud enough that the back of the room can hear you, pronounce each word clearly, and try not to read too fast.

- Maintain good eye contact with your audience. Look down to read and up to speak.

- Match gestures to the content of the speech, and avoid distracting hand or foot movements.

- If there is no podium, hold the manuscript at waist height.

Extemporaneous Presentations

Extemporaneous presentations are carefully planned and rehearsed presentations, delivered in a conversational manner using brief notes or a slide deck. By using notes rather than a full manuscript, the extemporaneous presenter can establish and maintain eye contact with the audience and assess how well they are understanding the presentation as it progresses.

To avoid over-reliance on notes or slides, you should have strong command of your subject matter. Then select an organizational pattern that works well for your topic. Your notes or slide deck should reflect this organizational pattern. In preparation, create an outline of your speech.

Watch some of the following 10-minute video of a champion speaker presenting an extemporaneous speech at the 2017 International Extemporaneous Speaking National Champion. :

(Direct link to 2017 International Extemporaneous Speaking National Champion video)

Presenting extemporaneously has some advantages. It promotes the likelihood that you, the speaker, will be perceived as knowledgeable and credible since you know the speech well enough that you don’t need to read it. In addition, your audience is likely to pay better attention to the message because it is engaging both verbally and non-verbally. It also allows flexibility; you are working from the strong foundation of an outline, but if you need to delete, add, or rephrase something at the last minute or to adapt to your audience, you can do so.

Adequate preparation cannot be achieved the day before you’re scheduled to present, so be aware that if you want to present a credibly delivered speech, you will need to practice many times. Extemporaneous presenting is the style used in the great majority of business presentation situations.

Memorized Speaking

Memorized speaking is the recitation of a written message that the speaker has committed to memory. Actors, of course, recite from memory whenever they perform from a script in a stage play, television program, or movie scene. When it comes to speeches, memorization can be useful when the message needs to be exact and the speaker doesn’t want to be confined by notes.

The advantage to memorization is that it enables the speaker to maintain eye contact with the audience throughout the speech. Being free of notes means that you can move freely around the stage and use your hands to make gestures. If your speech uses visual aids, this freedom is even more of an advantage. However, there are some real and potential costs.

First, unless you also plan and memorize every vocal cue (the subtle but meaningful variations in speech delivery, which can include the use of pitch, tone, volume, and pace), gesture, and facial expression, your presentation will be flat and uninteresting, and even the most fascinating topic will suffer. Second, if you lose your place and start trying to ad lib, the contrast in your style of delivery will alert your audience that something is wrong. More frighteningly, if you go completely blank during the presentation, it will be extremely difficult to find your place and keep going. Memorizing a presentation takes a great deal of time and effort to achieve a natural flow and conversational tone.

Check Your Knowledge (12 Questions)

References

University of Hawai’i Maui Community College. (2002). Commemorative speech objectives and tips. https://www.hawaii.edu/mauispeech/html/commemorative_speech1.html